Cinema Comparat/Ive Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema As a Tool for Development

MSc Thesis Cinema as a Tool for Development Investigating the Power of Mobile Cinema in the Latin American Context By Philippine Sellam 1 In partial requirement of: Master of Sustainable Development/ International Development track Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University Student: Philippine Sellam (3227774) [email protected] Under the supervision of: Gery Nijenhuis Utrecht, August 2014 Cover Picture and full page pictures between chapters: The public of mobile cinema/Fieldwork 2014 Title font: ‘Homeless font’ purchased from the Arells Foundation (www.homelessfonts.org) 2 Everything you can imagine is real - Picasso 3 Abstract During the last fifteen years, mobile cinema has sparked new interest in the cinema and development sectors. Taking cinema out of conventional theatres and bringing it to the people by transporting screening equipment on trucks, bicycles or trains and setting up ephemeral cinemas in the public space. Widening the diffusion of local films can provide strong incentives to a region or a country’s cinematographic industry and stimulate the production of independent films on socially conscious themes. But the main ambition of most mobile cinema projects is to channel the power of cultural community encounters to trigger critical social reflections and pave the way for social transformation. Just as other cultural activities, gathering to watch a film can bring new inspirations and motivations, which are subjective drivers for actor-based and self-sustained community change. Research is needed to substantiate the hypothesis that mobile cinema contributes to social change in the aforementioned sense. Therefore, the present work proposes to take an investigative look into mobile cinema in order to find out the ways and the extent to which it contributes to actor-based community development. -

Film, Photojournalism, and the Public Sphere in Brazil and Argentina, 1955-1980

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MODERNIZATION AND VISUAL ECONOMY: FILM, PHOTOJOURNALISM, AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA, 1955-1980 Paula Halperin, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Directed By: Professor Barbara Weinstein Department of History University of Maryland, College Park My dissertation explores the relationship among visual culture, nationalism, and modernization in Argentina and Brazil in a period of extreme political instability, marked by an alternation of weak civilian governments and dictatorships. I argue that motion pictures and photojournalism were constitutive elements of a modern public sphere that did not conform to the classic formulation advanced by Jürgen Habermas. Rather than treating the public sphere as progressively degraded by the mass media and cultural industries, I trace how, in postwar Argentina and Brazil, the increased production and circulation of mass media images contributed to active public debate and civic participation. With the progressive internationalization of entertainment markets that began in the 1950s in the modern cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires there was a dramatic growth in the number of film spectators and production, movie theaters and critics, popular magazines and academic journals that focused on film. Through close analysis of images distributed widely in international media circuits I reconstruct and analyze Brazilian and Argentine postwar visual economies from a transnational perspective to understand the constitution of the public sphere and how modernization, Latin American identity, nationhood, and socio-cultural change and conflict were represented and debated in those media. Cinema and the visual after World War II became a worldwide locus of production and circulation of discourses about history, national identity, and social mores, and a space of contention and discussion of modernization. -

História Do Cinema Brasileiro

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO ESPÍRITO SANTO CENTRO DE ARTES DEPARTAMENTO DE COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL Plano de Ensino Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo Campus Goiabeiras Curso: Cinema e Audiovisual Departamento Responsável: Comunicação Social Data de Aprovação (art. nº 91): Reunião do Departamento de Comunicação Social (Remota), em 3 de setembro de 2020. Docentes Responsáveis: Alexandre Curtiss Fabio Camarneiro Qualificação / atalho para o Currículo Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/3817609373788084 (Alexandre Curtiss) http://lattes.cnpq.br/5820527580375928 (Fabio Camarneiro) Disciplina: TÓPICOS ESPECIAIS EM AUDIOVISUAL I Código: COS 10416 (Tópicos em História do Cinema Brasileiro) Carga Horária Pré-requisito: Não possui Semestral: 60h Distribuição da Carga Horária Semestral Créditos: 03 Teórica Exercício Laboratório 30 30 0 Aspectos estéticos, históricos e políticos do cinema brasileiro. Tópicos da história do cinema brasileiro: o período silencioso, as chanchadas, o cinema de estúdio, o Cinema Novo, o cinema marginal, o documentário, a Embrafilme, o cinema da retomada e o cinema contemporâneo. Diretores pretos e diretoras mulheres. Objetivos: Capacitar os estudantes a compreender a periodização do cinema brasileiro conforme a historiografia clássica e ser capaz de criticá-la. Capacitar os estudantes a estabelecer relações entre os contextos históricos e políticos e a produção cultural cinematográfica. Capacitar os estudantes a debater as especificidades do cinema brasileiro frente à América Latina e à produção mundial. Conteúdo Programático HISTÓRIA -

Brazilian Films and Press Conference Brunch

rTh e Museum of Modern Art No. 90 FOR REL.EIASE* M VVest 53 street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 245-3200 Cable: Modernart ^ ^ , o -, . ro ^ Wednesday^ October 2, i960 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART INTRODUCES BRAZILIAN FILMS In honor of Brazil's new cinema movement called Cinema NovO; The Museum of Modern Art will present a ten-day program of features and shorts that reflect the recent changes and growth of the film industry in that country. Cinema Novo: Brasil. the New Cinema of Brazil, begins October 1. and continues through I October 17th. Nine feature-length films;, the work of eight young directors; who represent the New Wave of Brazil^ will be shown along with a selection of short subjects. Adrienne Mancia, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, assembled the program. In the past seven years, the Brazilians have earned i+0 international awards. In Berlin, Genoa and Moscow. Brazilian film retrospectives have been held in acknowledgement of the vigorous Cinema Novo that has taken root in that country. Cinema Novo of Brazil has had a stormy history. The first stirring began in the early 50*8 with the discontent of young filmmakers who objected to imitative Hollywood musical comedies, known as "chanchadas," which dominated traditional Brazilian cinema. This protest found a response araong young film critics who were inspired by Italian neo- realism and other foreign influences to demand a cinema indigenous to Brazil. A bandful of young directors were determined to discover a cinematic language that would reflect the nation's social and human problems. The leading exponent of Cinema Novo, Glauber Rocha, in his late twenties, stated the commitLment of Brazil's youthful cineastes when he wrote: "In our society everything is still I to be done: opening roads through the forest, populating the desert, educating the masses, harnessing the rivers. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

Histórias E Causos Do Cinema Brasileiro

Zelito Viana Histórias e Causos do Cinema Brasileiro Zelito Viana Histórias e Causos do Cinema Brasileiro Betse de Paula São Paulo, 2010 GOVERNO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO Governador Alberto Goldman Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo Diretor-presidente Hubert Alquéres Coleção Aplauso Coordenador Geral Rubens Ewald Filho No Passado Está a História do Futuro A Imprensa Oficial muito tem contribuído com a sociedade no papel que lhe cabe: a democra- tização de conhecimento por meio da leitura. A Coleção Aplauso, lançada em 2004, é um exemplo bem-sucedido desse intento. Os temas nela abordados, como biografias de atores, di- retores e dramaturgos, são garantia de que um fragmento da memória cultural do país será pre- servado. Por meio de conversas informais com jornalistas, a história dos artistas é transcrita em primeira pessoa, o que confere grande fluidez ao texto, conquistando mais e mais leitores. Assim, muitas dessas figuras que tiveram impor- tância fundamental para as artes cênicas brasilei- ras têm sido resgatadas do esquecimento. Mesmo o nome daqueles que já partiram são frequente- mente evocados pela voz de seus companheiros de palco ou de seus biógrafos. Ou seja, nessas histórias que se cruzam, verdadeiros mitos são redescobertos e imortalizados. E não só o público tem reconhecido a impor- tância e a qualidade da Aplauso. Em 2008, a Coleção foi laureada com o mais importante prêmio da área editorial do Brasil: o Jabuti. Concedido pela Câmara Brasileira do Livro (CBL), a edição especial sobre Raul Cortez ganhou na categoria biografia. Mas o que começou modestamente tomou vulto e novos temas passaram a integrar a Coleção ao longo desses anos. -

Lista De Filmes Brasileiros Disponíveis Para Empréstimo Embaixada Do Brasil Em Adis Abeba Bole Sub-City, Kebele 02, House Nr

Lista de Filmes Brasileiros disponíveis para Empréstimo Embaixada do Brasil em Adis Abeba Bole Sub-City, Kebele 02, House Nr. 2830 Tel: +251(0)116-620-401 E-mail: [email protected] 1. “2 Filhos de Francisco” (drama/biográfico), de Brenno Silveira (2005) 2. “2 perdidos numa noite suja” (drama), de Braz Chediak (2002) 3. “Abril despedaçado” (drama), de Walter Salles (2001) 4. “Anahy de las misiones” (ficção histórica), de Sergio Silva (2000) 5. “Bossa Nova” (comédia/romance), de Bruno Barreto (1999) 6. “Brava Gente Brasileira” (drama),de Lucia Murat (2000) 7. “Cabra-cega” (drama), de Toni Venturi (2006) 8. “Caramuru, a invenção do Brasil” (comédia), de Guel Arraes (2003) 9. “Carandiru” (drama), de Hector Babenco (2003) 10. “Central do Brasil” (drama), de Walter Salles (1998) 11. “Cidade baixa” (drama), de Sergio Machado (2005) 12. “Cidade de Deus“ (ação/drama) , de Fernando Meirelles (2002) 2DVD 13. “Dias de Nietzsche em Turim” (drama biográfico), de Julio Bressane (2004) 14. “Domésticas, o filme” (comédia), de Fernando Meirelles (2001) 15. “Durval Discos” (comédia), de Anna Muylaert (2002) 16. “Ed Mort” (comédia), de Alain Fresnot (2005) 17. “Edifício Master” (documentário), de Eduardo Coutinho (2002) 18. “Entreatos” (documentário), de João Moreira Salles (2006) 19. “Estorvo” (drama), de Ruy Guerra (2001) 20. “Fala tu” (documentário), de Guilherme Coelho (2003) 21. “Filme de Amor” (drama), de Julio Bressane (2003) 22. “Canudos” (drama), de Sergio Rezende (2005) 23. “Iracema, Uma Transa Amazônica” (drama), de J. Bodanzky e Orlando Senna (2005) 24. “Justiça” (documentário), de Maria Augusta Ramos (2004) 25. “Lamarca” (drama biográfico), de Sergio Rezende (2005) 26. -

CRISTINAALVARESBESKOWVC.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÕES E ARTES PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM MEIOS E PROCESSOS AUDIOVISUAIS O documentário no Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano: olhares e vozes de Geraldo Sarno (Brasil), Raymundo Gleyzer (Argentina) e Santiago Álvarez (Cuba) CRISTINA ALVARES BESKOW São Paulo 2016 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÕES E ARTES PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM MEIOS E PROCESSOS AUDIOVISUAIS O documentário no Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano: olhares e vozes de Geraldo Sarno (Brasil), Raymundo Gleyzer (Argentina) e Santiago Álvarez (Cuba) CRISTINA ALVARES BESKOW Tese de doutorado apresentada à Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do título de Doutora em Ciências pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Meios e Processos Audiovisuais. Área de concentração: Cultura Audiovisual e Comunicação Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Marília da Silva Franco São Paulo 2016 Nome do Autor: Cristina Alvares Beskow Título da Tese: O Documentário no Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano: olhares e vozes de Geraldo Sarno (Brasil), Raymundo Gleyzer (Argentina) e Santiago Álvarez (Cuba) Presidente da Banca: Prof. Dra. Marília da Silva Franco Banca Examinadora: Prof. Dr. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Instituição: _________________________ Assinatura___________________________________________ Prof. Dr. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Instituição: _________________________ Assinatura___________________________________________ -

Comparing the New Cinemas of France, Japan and Brazil

WASEDA RILAS JOURNALWaves NO. on Different4 (2016. 10) Shores: Comparing the New Cinemas of France, Japan and Brazil Waves on Different Shores: Comparing the New Cinemas of France, Japan and Brazil Richard PEÑA Abstract What is the place of “comparative” film historiography? In an era that largely avoids over-arching narratives, what are the grounds for, and aims of, setting the aesthetic, economic or technological histories of a given national cinema alongside those of other nations? In this essay, Prof. Richard Peña (Columbia University) examines the experiences of three distinct national cinemas̶those of France, Japan and Brazil̶that each witnessed the emer- gence of new movements within their cinemas that challenged both the aesthetic direction and industrial formats of their existing film traditions. For each national cinema, three essential factors for these “new move” move- ments are discussed: (1) a sense of crisis in the then-existing structure of relationships within their established film industries; (2) the presence of a new generation of film artists aware of both classic and international trends in cinema which sought to challenge the dominant aesthetic practices of each national cinema; and (3) the erup- tion of some social political events that marked not only turning points in each nation’s history but which often set an older generation then in power against a defiant opposition led by the young. Thus, despite the important and real differences among nations as different as France, Japan and Brazil, one can find structural similarities related to both the causes and consequences of their respective cinematic new waves. Like waves, academic approaches to various dis- personal media archives resembling small ciné- ciplines seem to have a certain tidal structure: mathèques, the idea of creating new histories based on sometimes an approach is “in,” fashionable, and com- linkages between works previously thought to have monly used or cited, while soon after that same little or no connection indeed becomes tempting. -

Cinema Nacional E Ensino De Sociologia : Como Trechos De Filme E

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO CURITIBA 2016 ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Educação, no Curso de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Setor de Educação, Linha de Pesquisa Cultura, Escola e Ensino da Universidade Federal do Paraná-UFPR. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Rosa Maria Dalla Costa CURITIBA 2016 Dedico este trabalho a todos os profissionais da educação que estiverem na praça Nossa Senhora de Salete (Curitiba) no dia 29 de abril de 2015. RESUMO Estudar o cinema na perspectiva da Sociologia passa, antes de tudo, por uma questão cultural, mas não se limita a isto. Pensar os desdobramentos que cercam a temática do cinema é, também, se deparar com questões de ordem social, política, econômica e ideológica das relações entre indivíduo e sociedade, levando-se em conta que as mesmas são estruturadas a partir das esferas da produção e do consumo. Este conjunto de relações constitui por si mesmo uma problemática das Ciências Sociais. Por isso, quando se trata da sala de aula, a projeção de um filme ou de um trecho de filme, não pode se restringir somente ao lazer ou ao entretenimento. Com a implantação da Lei n° 13.006 de junho de 2014, que torna obrigatória a exibição por 2 horas mensais de filmes nacionais nas escolas, a busca por maneiras de trabalhar o cinema nacional de forma significativa na sala de aula tornou-se premente.Foi a busca pela identificação de diferentes perspectivas de trabalho com cinema nacional no ensino de Sociologia na Educação Básica que motivou esta pesquisa. -

Half Title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS in CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN

<half title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS</half title> i Traditions in World Cinema General Editors Linda Badley (Middle Tennessee State University) R. Barton Palmer (Clemson University) Founding Editor Steven Jay Schneider (New York University) Titles in the series include: Traditions in World Cinema Linda Badley, R. Barton Palmer, and Steven Jay Schneider (eds) Japanese Horror Cinema Jay McRoy (ed.) New Punk Cinema Nicholas Rombes (ed.) African Filmmaking Roy Armes Palestinian Cinema Nurith Gertz and George Khleifi Czech and Slovak Cinema Peter Hames The New Neapolitan Cinema Alex Marlow-Mann American Smart Cinema Claire Perkins The International Film Musical Corey Creekmur and Linda Mokdad (eds) Italian Neorealist Cinema Torunn Haaland Magic Realist Cinema in East Central Europe Aga Skrodzka Italian Post-Neorealist Cinema Luca Barattoni Spanish Horror Film Antonio Lázaro-Reboll Post-beur Cinema ii Will Higbee New Taiwanese Cinema in Focus Flannery Wilson International Noir Homer B. Pettey and R. Barton Palmer (eds) Films on Ice Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport (eds) Nordic Genre Film Tommy Gustafsson and Pietari Kääpä (eds) Contemporary Japanese Cinema Since Hana-Bi Adam Bingham Chinese Martial Arts Cinema (2nd edition) Stephen Teo Slow Cinema Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge Expressionism in Cinema Olaf Brill and Gary D. Rhodes (eds) French Language Road Cinema: Borders,Diasporas, Migration and ‘NewEurope’ Michael Gott Transnational Film Remakes Iain Robert Smith and Constantine Verevis Coming-of-age Cinema in New Zealand Alistair Fox New Transnationalisms in Contemporary Latin American Cinemas Dolores Tierney www.euppublishing.com/series/tiwc iii <title page>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS Dolores Tierney <EUP title page logo> </title page> iv <imprint page> Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. -

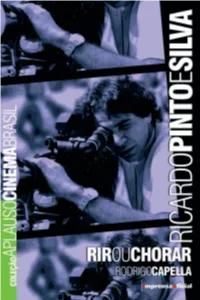

Ricardo Pinto E Silva

Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Ricardo miolo.indd 1 9/10/2007 17:34:34 Ricardo miolo.indd 2 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Rodrigo Capella São Paulo, 2007 Ricardo miolo.indd 3 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Governador José Serra Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo Diretor-presidente Hubert Alquéres Diretor Vice-presidente Paulo Moreira Leite Diretor Industrial Teiji Tomioka Diretor Financeiro Clodoaldo Pelissioni Diretora de Gestão Corporativa Lucia Maria Dal Medico Chefe de Gabinete Vera Lúcia Wey Coleção Aplauso Série Cinema Brasil Coordenador Geral Rubens Ewald Filho Coordenador Operacional e Pesquisa Iconográfica Marcelo Pestana Projeto Gráfico Carlos Cirne Editoração Aline Navarro Assistente Operacional Felipe Goulart Tratamento de Imagens José Carlos da Silva Revisão Amancio do Vale Dante Pascoal Corradini Sarvio Nogueira Holanda Ricardo miolo.indd 4 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Apresentação “O que lembro, tenho.” Guimarães Rosa A Coleção Aplauso, concebida pela Imprensa Oficial, tem como atributo principal reabilitar e resgatar a memória da cultura nacional, biogra- fando atores, atrizes e diretores que compõem a cena brasileira nas áreas do cinema, do teatro e da televisão. Essa importante historiografia cênica e audio- visual brasileiras vem sendo reconstituída de manei ra singular. O coordenador de nossa cole- ção, o crítico Rubens Ewald Filho, selecionou, criteriosamente, um conjunto de jornalistas especializados para rea lizar esse trabalho de apro ximação junto a nossos biografados. Em entre vistas e encontros sucessivos foi-se estrei- tan do o contato com todos. Preciosos arquivos de documentos e imagens foram aber tos e, na maioria dos casos, deu-se a conhecer o universo que compõe seus cotidianos.