Masterarbeit / Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S Secretfashion Show 2014,Outfit in Viale Alberato,Cupc

In the middle of nowhere IT: Buongiorno! Come state? Avete passato bene il weekend prolungato? Io sono rimasta a casa, ho fatto l’albero e ho decorato l’esterno della casa. Domenica sono andata con Piero a vedere un bosco in Slovenia, di solito la gente normale passa le domeniche in famiglia o va in giro, io, invece, le passo nei boschi Eravamo in un posto che è tagliato fuori dal mondo e dove non c’era il guardrail…solo Piero è capace di trovare posti così sperduti e dimenticati?? All’inizio ho pensato di non pubblicare queste foto, perchè non sono venute proprio benissimo, le abbiamo fatte velocemente, perché fuori erano quasi 0 gradi. Spero che comunque vi piacciano. Vi auguro buon mercoledi! EN: Hello! How are you? I have spent the weekend at home, I did the tree and I decorated outside the home. On Sunday I went with Piero to see a forest in Slovenia, the usual, normal people pass Sunday in family or around, instead I pass Sunday in the forests We were in a place that is cut outside the world and where not even a guardrail, only Piero is capable of to find places so astray and forgotten ?? At the beginning I thought about not to publish these photos, because there are not the best, we have done them quickly, and outside were almost 0 degrees. I hope that however you like it. I wish you good Wednesday! SI: Zivijo! Kako ste? Jaz sem vikend prezivela doma, sem okrasila drevo in zunanjost hise. V nedeljo pa sva si sla s Pierotom ogledati en gozd v Slovenijo, obicajno normalni ljudje prezivijo nedelje v krogu druzine ali odzunaj, jaz pa jih prezivljam v gozdovih Sla sva si ogledat en gozd, odrezan od sveta, kjer ni niti obcestne ograje, samo Piero je zmozen dobiti kraje, ki so pozabljeni in odrezani od sveta?? Na zacetku sem mislila, da ne objavim teh fotografij, ker niso prov najboljse, smo jih na hitro naredili, ker je bilo odzunaj okrog 0 stopinj. -

Taís De F. Saldanha Iensen TRABALHO FINAL DE GRADUAÇÃO II O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRI

Taís de F. Saldanha Iensen TRABALHO FINAL DE GRADUAÇÃO II O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRIAS EVIDENTES NO VICTORIA’S SECRETS FASHION SHOW Santa Maria, RS 2014/1 Taís de F. Saldanha Iensen O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRIAS EVIDENTES NO VICTORIA’S SECRETS FASHION SHOW Trabalho Final de Graduação II (TFG II) apresentado ao Curso de Publicidade e Propaganda, Área de Ciências Sociais, do Centro Universitário Franciscano – Unifra, como requisito para conclusão de curso. Orientadora: Prof.ª Me. Morgana Hamester Santa Maria, RS 2014/1 2 Taís de F. Saldanha Iensen O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRIAS EVIDENTES NO VICTORIA’S SECRETS FASHION SHOW _________________________________________________ Profª Me. Morgana Hamester (UNIFRA) _________________________________________________ Prof Me. Carlos Alberto Badke (UNIFRA) _________________________________________________ Profª Claudia Souto (UNIFRA) 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Inicialmente gostaria de agradecer aos meus pais por terem me proporcionado todas as chances possíveis e impossíveis para que eu tivesse acesso ao ensino superior que eles nunca tiveram, meus irmãos por terem me aguentado e me ajudado durante esse tempo, meus tios e tias, que da mesma forma que meus pais, sempre me incentivaram a estudar, meus avós que sempre me ajudarem nos momentos difíceis com sua sabedoria e experiência. Gostaria também de agradecer em especial à tia Edi, minha dinda, minha madrinha de coração que junto com meus pais, sempre me deu todo tipo de apoio para que eu não desistisse, mesmo nos momentos mais difíceis. Meu amigo Rafa que me deu a ideia do tema e ter me ajudado até a finalização do mesmo. -

Abiti Da Sposa: 16 Modelle Famose Ei Loro Vestiti Di

Leggi l'articolo su beautynews Abiti da sposa: 16 modelle famose e i loro vestiti di nozze Abiti da sposa: ispirazione… top model Difficile vedere l'album di nozze di una star, figuriamoci di una modella che custodisce gelosamente la sua vita privata ancora più di una star di Hollywood. Ma queste 16 modelle, su Instagram o in un raro scatto “rubato” in loco dopo il fatidico sì, hanno condiviso con i loro fan una (o più) foto del giorno più bello della loro vita, con i loro abiti da sposa ben in vista. Behati Prinsloo, per esempio, ha ritirato fuori il suo abito da sposa, firmato Alexander Wang, di recente, tramite Instagram Stories. Una creazione minimal ma da vera rockstar, grazie a scollature e spacchi vertiginosi. pagina 1 / 19 pagina 2 / 19 Behati Prinsloo Behati Prinsloo in Alexander Wang, via Instagram Stories E, come accade in passerella, anche nella loro vita privata le modelle insegnano sempre qualcosa in termini di stile, griffatissimo per altro. Quindi, future spose, prendete nota. Perché se credete che le top model scelgano modelli classici per il “sì” vi sbagliate. Non date retta alle apparenze o a quello che ci ha sempre insegnato Carrie Bradshaw a proposito delle donne dal corpo più perfetto al mondo. Le modelle sono esattamente come noi, certo con gambe chilometriche e un viso che buca lo schermo. Ma quando si è in procinto di camminare lungo la navata, proverete lo stesso brivido di una di queste top model, ve lo garantiamo. Quindi perché non attingere a un po' del loro modelling-vibe per essere una sposa classica alla Christy Turlington o Karlie Kloss, una rockstar come Kate Moss (qui in abito da sposa per motivi di lavoro, ovvero sulle passerelle), Behati Prinsloo o Hanne Gaby Odiele, una sirena come Hailey Bieber e Gisele Bündchen o un'anticonformista come Cindy Crawford, Kristen McMenamy e Stella Tennant. -

Karlova Univerzita V Praze

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH VĚD Institut Komunikačních studií a žurnalistiky Katedra Mediálních studií Sémiotická analýza komunikace značky Victoria’s Secret Diplomová práce Autor práce: Bc. Kristýna Jílková Studijní program: Mediální studia Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Otakar Šoltys, CSc. Rok obhajoby: 2018 Prohlášení 1. Prohlašuji, že jsem předkládanou práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. 2. Prohlašuji, že práce nebyla využita k získání jiného titulu. 3. Souhlasím s tím, aby práce byla zpřístupněna pro studijní a výzkumné účely. V Praze dne 11. 5. 2018 Bc. Kristýna Jílková Bibliografický záznam JÍLKOVÁ, Kristýna. Sémiotická analýza komunikace značky Victoria‘s Secret. Praha, 2018. 71 s. Diplomová práce (Mgr.) Univerzita Karlova, Fakulta sociálních věd, Institut komunikačních studií a žurnalistiky. Katedra mediálních studií. Vedoucí diplomové práce PhDr. Otakar Šoltys, CSc. Rozsah práce: 71 s. Anotace Práce přistupuje k persvazivní komunikaci vybrané firmy z hlediska sémiotiky. Věnuje se hlavním oblastem komunikace firmy Victoria's Secret, zejména známé The Victoria's Secret Fashion Show. Zvolených sedm videí v období tří let pokrývá hlavní úsek komunikace (televizní reklama, televizní módní přehlídka) a prostředky, které firma využívá k oslovení svého publika. Zajímalo nás, jakým způsobem je konstruováno sdělení, jaká jsou převažující témata, a zda všechny roviny sdělení odpovídají propagovaným hodnotám firmy. Vybraná metoda výzkumu je sémiotická analýza v pojetí Rolanda Barthese a jeho terminologický rámec pro odhalování ideologie skryté ve sděleních. Vzorek je rozebrán z hlediska děje, rozlišení na primární a sekundární znaky, popis technických kódů a syntagmatického a paradigmatického řazení. Postupně jsou pak identifikovány významy znaků v první a druhé rovině označování a pojmenovány mýty v promluvě těchto sdělení. -

2013 Victoria's Secret Fashion Show

PRESS ROOM EXCLUSIVELY FOR THE MEDIA THIS JUST IN… …from CBS Entertainment SEVEN-TIME GRAMMY® AWARD WINNER TAYLOR SWIFT AND GRAMMY AWARD-NOMINATED ARTIST FALL OUT BOY TO PERFORM ON “THE VICTORIA’S SECRET FASHION SHOW,” TUESDAY, DEC. 10 ON THE CBS TELEVISION NETWORK A Great Big World and UK Newcomers Neon Jungle Will Also Perform Seven-time GRAMMY® Award-winning artist Taylor Swift, GRAMMY Award-nominated artist Fall Out Boy, A Great Big World and Neon Jungle will perform on THE VICTORIA’S SECRET FASHION SHOW, to be broadcast Tuesday, Dec. 10 (10:00-11:00 PM, ET/PT) on the CBS Television Network. This year’s fashion show will include world-famous Victoria’s Secret Angels Adriana Lima, Alessandra Ambrosio, Lily Aldridge, Candice Swanepoel, Lindsay Ellingson, Karlie Kloss, Doutzen Kroes, Behati Prinsloo and many more. The lingerie runway show will also include pink carpet interviews, model profiles and a behind-the-scenes look at the making of the world’s most celebrated fashion show. Lauded by The New York Times as “one of the most important pop artists of the last decade,” and by Rolling Stone as “one of the few genuine rock stars we’ve got these days,” singer/songwriter Taylor Swift is a seven-time GRAMMY winner, and at 20, was the youngest winner in history of the music industry’s highest honor, the GRAMMY for Album of the Year in 2010. She is the only female artist in music history (and just the fourth artist ever) to twice have an album hit the one million first-week sales figure, and is the first artist since the Beatles (and the only female artist in history) to log six or more weeks at #1 with three consecutive studio albums. -

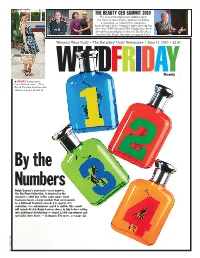

By the Numbers

THE BEAUTY CEO SUMMIT 2010 The best of intentions have bubbled up in the worst of times. Fresh, innovative thinking is emerging, as evidenced by comments made by some of the industry’s top leaders during the recent WWD Beauty CEO Summit that drew 230 top beauty-industry leaders to The Breakers hotel in Palm Beach. For more, see pages 4 to 8. Women’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • June 11, 2010 • $3.00 WWDFRIDaBeautyy s RESORT: Looks from Louis Vuitton (above), Tory Burch, Proenza Schouler and J.Mendel, pages 10 and 11. By the Numbers Ralph Lauren’s new men’s scent quartet, the Big Pony Collection, is inspired by the designer’s shirt line of the same name. Each fragrance bears a large number that corresponds to a different fragrance mood: 1 is sporty, 2 is seductive, 3 is adventurous and 4 is stylish. The scents will launch first in Ralph Lauren stores in July before rolling into additional distribution — about 2,500 department and specialty store doors — in August. For more, see page 12. PHOTO BY GEORGE CHINSEE PHOTO BY 2 WWD, FRIDAY, JUNE 11, 2010 WWD.COM Thurman, Karan Line Up Against Cancer By Marc Karimzadeh ity shopping weekend, meanwhile, is scheduled to take place Oct. 21 to 24. Two percent of that NEW YORK — Uma Thurman and Donna Karan weekend’s sales will be donated to local and WWDfriDaBeautyy are teaming to combat women’s cancer. national women’s cancer organizations and re- FASHION Saks Fifth Avenue and The Breast Cancer search centers. -

Should Magazines Sell Stuff? Church and State Issues Aside

Fashion. Beauty. Business. TOMMY FASHION TOUGH TUNE IN CHINA NIGHT The shuttering of JUN 2015 Tommy Hilfiger took All the winners, the Band of Outsiders No.1 his show on the road red carpet and the exemplifies the and opened his first after-party action at challenges young flagship in Beijing. the CFDA Awards. designers face. Markets p. 26 Eye p. 35 Markets p. 24 HARD SELL Should magazines sell stuff? Church and State issues aside, “Times are tough for independent labels.” independent labels.” for tough “Times are it hasn’t worked yet. Will it ever? KRIS VAN ASSCHE KRIS VAN Hard Sell US $9.99 JAPAN ¥1500 CANADA $13 CHINA ¥80 UK £ 8 HONG KONG HK100 EUROPE € 11 INDIA 800 Edward Nardoza EDITOR IN CHIEF Pete Born EXECUTIVE EDITOR, BEAUTY Bridget Foley The EXECUTIVE EDITOR James Fallon EDITOR Robb Rice Features GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR John B. Fairchild 1927 — 2015 MANAGING EDITOR Peter Sadera Hard Sell MANAGING EDITOR, Dianne M. Pogoda FASHION/SPECIAL REPORTS 46 As newsstand and EUROPEAN EDITOR Miles Socha DEPUTY MANAGING EDITOR Evan Clark advertising revenues plunge, NEWS DIRECTOR Lisa Lockwood DEPUTY EDITOR, DATA AND ANALYSIS Arthur Zaczkiewicz magazine companies are DEPUTY FASHION EDITOR Donna Heiderstadt SITTINGS DIRECTOR Alex Badia desperately seeking new SENIOR EDITOR, RETAIL David Moin SENIOR EDITOR, SPECIAL PROJECTS, Arthur Friedman TEXTILES & TRADE revenue streams. Does the SENIOR EDITORS, FINANCIAL Arnold J. Karr, Vicki M. Young ASSOCIATE EDITOR Lorna Koski answer reside in magazine BUREAU CHIEF, LONDON Samantha Conti BUREAU CHIEF, MILAN Luisa Zargani e-commerce? BUREAU CHIEF, LOS ANGELES Marcy Medina ASIAN EDITOR Amanda Kaiser BUREAU CHIEF, WASHINGTON Kristi Ellis SENIOR FASHION EDITOR Bobbi Queen The Lone Ranger ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jenny B. -

The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: from the Sidewalk to the Catwalk, the First International Exhibition of This Celebrated French Couturier’S Work

It’s official! Only East Coast venue of this exhibition of innovative work by the celebrated French fashion designer. New creations presented for the first time. For the last four decades, Jean Paul Gaultier has shaped the look of contemporary fashion with his avant-garde creations and cutting-edge designs. The Brooklyn Museum will be the only East Coast venue for The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk, the first international exhibition of this celebrated French couturier’s work. This spectacular overview of Gaultier’s extensive oeuvre will include exclusive material not exhibited in previous venues of the tour, such as pieces from his recent haute couture and ready-to-wear collections and stage costumes worn by Beyoncé. Jean Paul Gaultier. © Rainer Torrado The French couturier says of the Brooklyn presentation: “I am proud and honored that this exhibition will be presented here, where the true spirit of New York lives on. I was always fascinated by Gaultier’s reputation for witty and daring designs New York, its energy, the skyscrapers of Manhattan, and a ceaseless interest in society, identity, and that special view of the sky between the tall beauty born of difference has earned him a place buildings…. On one of my first trips I decided to walk in fashion history. The Brooklyn presentation all the way uptown from the Village until Harlem. will include Gaultier costumes never before seen It took me the whole day, and I will never forget the in New York, such as items graciously lent by pleasure of discovering this great city. -

Universidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul Faculdade De Biblioteconomia E Comunicação Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Comunicação E Informação

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL FACULDADE DE BIBLIOTECONOMIA E COMUNICAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO E INFORMAÇÃO TESE DE DOUTORADO O DISCURSO HÍBRIDO DO JORNALISMO DE MODA: estratégias do Jornalismo, da Publicidade e da Estética Débora Elman Porto Alegre 2017 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL FACULDADE DE BIBLIOTECONOMIA E COMUNICAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO E INFORMAÇÃO TESE DE DOUTORADO O DISCURSO HÍBRIDO DO JORNALISMO DE MODA: estratégias do Jornalismo, da Publicidade e da Estética Débora Elman Tese apresentada para obtenção do título de Doutora pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação e Informação da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Marcia Benetti Porto Alegre 2017 Débora Elman O DISCURSO HÍBRIDO DO JORNALISMO DE MODA: estratégias do Jornalismo, da Publicidade e da Estética Tese apresentada para obtenção do título de Doutora pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação e Informação da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. BANCA EXAMINADORA _____________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Marcia Benetti (Orientadora) _____________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Thais Helena Furtado | UNISINOS _____________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Solange Mittmann | UFRGS _____________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Joana Bosak de Figueiredo | UFRGS _____________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Daniela Maria Schmitz | UFRGS _____________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Sean Aquere Hagen (Suplente) | UFRGS Para meu pai, José Elman (in memoriam). AGRADECIMENTOS Em 2012 eu não tinha uma ideia formada do que viria pela frente nos quatro anos seguintes. Hoje posso dizer que foi muito, muito bom passar por tudo isso com a ajuda de tanta gente querida. Quero agradecer aos colegas da Faculdade Senac Porto Alegre, aos meus alunos e aos amigos que acompanharam, doaram revistas, foram pacientes e compreensivos nesse tempo todo. -

Aukční Katalog

EXKLUZIVNÍ AUKCE ČESKÉHO, SLOVENSKÉHO A EVROPSKÉHO VÝTVARNÉHO UMĚNÍ Muzika František, pol. 163 14. 11. 2015 OD 13.30 hoDin HOTEL HILTON PRAGUE, POBŘEŽNÍ 1, PRAHA 8 Jíra Josef, pol. 134 Kars Georges, pol. 140 EXKLUZIVNÍ AUKCE ČESKÉHO, SLOVENSKÉHO A EVROPSKÉHO VÝTVARNÉHO UMĚNÍ 14. 11. 2015 OD 13.30 hoDin Hotel HILTON PRAGUE, Pobřežní 1, Praha 8 aukční DůM Tel.: +420 224 211 087 Mobil: +420 602 233 723 +420 776 666 648 Fax: +420 224 211 087 +420 274 780 957 e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.galerieartpraha.cz Galerie ART Praha, spol. s r. o. Staroměstské náměstí 20/548 Praha 1 4 aukčNÍ VYHLÁška Aukční vyhláška je určená k vyvěšení 1 měsíc před konáním aukce VI. v Galerii Art Praha, dále jejím sídle na Praze 10, a v místě konání aukce v den aukce, Platba a zkrácené znění je i v aukčním katalogu a na webových stránkách Galerie. Je též Cenu dosaženou vydražením nelze dodatečně snížit (nelze smlouvat), cenu součástí aukčního protokolu – viz podpisy stran. dosaženou vydražením je vydražitel povinen uhradit dražebníkovi v hoto- vosti, či platební kartou o nejbližší platební pauze. Platbu převodem v přípa- AUKČNÍ VYHLÁŠKA dech, kdy není podle zákona povinná, nebo jiným způsobem úhrady, je třeba dopře- o konání veřejné dobrovolné společné aukce věcí movitých du dohodnout. (obrazy, sochy, objekty) nejvyšší nabídce. 1. Při platbě do 200 000 Kč včetně aukční přirážky, je vydražitel povinen zaplatit I. ihned! Dražebník, Aukční dům GALERIE ART PRAHA, spol. s r.o., Praha 1, Staroměstské 2. Od 200 000 Kč–500 000 Kč je vydražitel povinen zaplatit do 14 ti dnů, náměstí 20/548, Ič 48117421, DIč CZ 48117421, se sídlem Praha 10, U Hráze 6/144, 3. -

Präsentation Des Kalenders 2020 “Looking for Juliet” Von Paolo Roversi in Verona

PRESSEMITTEILUNG PIRELLI: PRÄSENTATION DES KALENDERS 2020 “LOOKING FOR JULIET” VON PAOLO ROVERSI IN VERONA In Kombination mit einem Kurzfilm sucht Paolo Roversi nach dem Wesen der Julia Verona, 3. Dezember 2019 — “Looking for Juliet”, der von Paolo Roversi realisierte Pirelli Kalender für das Jahr 2020, wurde heute im Opernhaus von Verona präsentiert. Paolo Roversi hat sich dabei von William Shakespeares zeitlosem Drama inspirieren lassen. In der 47. Ausgabe des The Cal™ spricht er mit Claire Foy, Mia Goth, Chris Lee, Indya Moore, Rosalía, Stella Roversi, Yara Shahidi, Kristen Stewart und Emma Watson als Protagonistinnen die „Julia, die in jeder Frau lebt“ an. In diesem Jahr verschmilzt der Kalender erstmals Fotografie und Film, da er von einem Kurzfilm begleitet wird. In dem 18-minütigen Kurzfilm spielt Paolo Roversi sich selbst als Filmregisseur und interviewt Kandidatinnen für die Rolle der Julia. Nacheinander treten sie vor die Kamera des Regisseurs, um die facettenreiche Julia durch ein breites Spektrum an Emotionen und Ausdrucksformen darzustellen. Die Story gliedert sich in zwei Abschnitte. Im ersten Abschnitt werden die Darstellerinnen ohne Schminke und ohne Kostüme abgelichtet, während sie das Set betreten. Sie werden aufgenommen, während sie mit Roversi über das Projekt reden, in der Hoffnung, dafür ausgewählt zu werden. Sie sprechen über ihre eigenen Erfahrungen und ihre Vorstellung von Julia. Die Darstellerinnen öffnen sich einer intimen und ganz vertrauten Erzählung. Im zweiten Abschnitt tragen sie die Kostüme der Darstellerinnen in Shakespeares Tragödie. Der Effekt, der erzeugt wird, ist eine Story, in der Wirklichkeit und Fiktion ineinander übergehen, und die Grenzen, wie auf einigen Bildern, verschwimmen. „Ich war auf der Suche nach einer reinen Seele, geprägt von Unschuld, Willensstärke, Schönheit, Zärtlichkeit und Mut. -

CORPO-ENCAIXE AO CORPO-MOLDE: a Construção De Um Corpo De Modelo

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE FEIRA DE SANTANA Departamento de Letras e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenho, Cultura e Interatividade CLARA SILVA PINHEIRO CORPO-ENCAIXE AO CORPO-MOLDE: a construção de um corpo de modelo ANEXO 2 – LOMBADA FEIRA DE SANTANA - BAHIA 2017 UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE FEIRA DE SANTANA Departamento de Letras e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenho, Cultura e Interatividade CLARA SILVA PINHEIRO CORPO-ENCAIXE AO CORPO-MOLDE: a construção de um corpo de modelo Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Desenho, Cultura e Interatividade da Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, na Área de Concentração Desenho, Registro e Memória Visual, Linha de Pesquisa Estudos Interdisciplinares em Desenho, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Desenho, Cultura e Interatividade, sob a orientação do Prof. Doutor Luís Vitor Castro Junior. FEIRA DE SANTANA - BAHIA 2017 Ficha Catalográfica – Biblioteca Central Julieta Carteado Pinheiro, Clara Silva P718c Corpo-encaixe ao corpo-molde: a construção de um corpo de modelo / Clara Silva Pinheiro. – Feira de Santana, 2017 114 f.: il. Orientador: Luiz Vitor Castro Junior. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenho, Cultura e Interatividade, 2017. 1. Desenho – Corpo de modelo. I. Castro Junior, Luiz Vitor, orient. UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE FEIRA DE SANTANA Departamento de Letras e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenho, Cultura e Interatividade CLARA SILVA PINHEIRO CORPO-ENCAIXE AO CORPO-MOLDE: a construção de um corpo de modelo Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Desenho, Cultura e Interatividade da Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Desenho, Cultura e Interatividade, avaliada pela Banca Examinadora composta pelos seguintes membros: BANCA EXAMINADORA Prof.