Grammaticalization, Constructions and the Incremental Development of Language: Suggestions from the Development of Degree Modifiers in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vietnamese Style Guide

Vietnamese Style Guide Contents What's New? .................................................................................................................................... 4 New Topics ................................................................................................................................... 4 Updated Topics ............................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 About This Style Guide ................................................................................................................ 5 Scope of This Document .............................................................................................................. 5 Style Guide Conventions .............................................................................................................. 5 Sample Text ................................................................................................................................. 5 Recommended Reference Material ............................................................................................. 6 Normative References .............................................................................................................. 7 Informative References ............................................................................................................ -

Chapter 1 Lexicalization Patterns

Chapter 1 Lexicalization Patterns 1 INTRODUCTION This study addresses the systematic relations in language between mean- ing and surface expression.1 (The word ``surface'' throughout this chapter simply indicates overt linguistic forms, not any derivational theory.) Our approach to this has several aspects. First, we assume we can isolate ele- ments separately within the domain of meaning and within the domain of surface expression. These are semantic elements like `Motion', `Path', `Figure', `Ground', `Manner', and `Cause', and surface elements like verb, adposition, subordinate clause, and what we will characterize as satellite. Second, we examine which semantic elements are expressed by which surface elements. This relationship is largely not one-to-one. A combina- tion of semantic elements can be expressed by a single surface element, or a single semantic element by a combination of surface elements. Or again, semantic elements of di¨erent types can be expressed by the same type of surface element, as well as the same type by several di¨erent ones. We ®nd here a range of universal principles and typological patterns as well as forms of diachronic category shift or maintenance across the typological patterns. We do not look at every case of semantic-to-surface association, but only at ones that constitute a pervasive pattern, either within a language or across languages. Our particular concern is to understand how such patterns compare across languages. That is, for a particular semantic domain, we ask if languages exhibit a wide variety of patterns, a com- paratively small number of patterns (a typology), or a single pattern (a universal). -

Your Name Here

THE HISTORY OF THE FUTURE: MORPHOPHONOLOGY, SYNTAX, AND GRAMMATICALIZATION by LAMAR ASHLEY GRAHAM (Under the Direction of L. Chadwick Howe) ABSTRACT The appearance of new verbal paradigms in the Romance languages – namely, the synthetic future indicative and conditional paradigms – has been one of the hallmark studies within the field of grammaticalization. Already existing in Latin was a synthetic future indicative paradigm, with a full complement of endings. Many researchers (Garey 1955; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Slobbe 2004; among others) have agreed that the infinitive + HABĒRE construction was the genesis of Romance future paradigms, obviating and completely replacing the disfavored Latin synthetic future. However, even after Latin evolved into Spanish, there still existed a duality between a periphrastic, analytic future and a paradigmatic, synthetic future. Said duality implied several syntactic and morphophonological characteristics of Old and Classical Spanish, some of which are no longer extant in the modern language. Through an empirical study, employing variable rules analyses, of Old and Classical Spanish texts, it is shown that the synthetic and analytic future and conditional were not always fully complementary of another, as the synthetic began to be used in contexts customarily reserved for the analytic construction. Within this work it will be shown how morphophonological and syntactic properties necessitated the existence of the analytic construction, especially the status of the auxiliary-turned-affix-turned- inflectional ending haber. Also of interest will be the manner in which the future and conditional paradigms derived syntactically in Old and Classical Spanish, with special attention lent to the role of cliticization principles in their structure. -

Lecture No .7 30Th March 2020 Word Formation Processes

جامعة المنيا، كلية اﻷلسن ,Mini University, Faculty of Alsun علم الصرف ، الفرقة الثانية، Morphology , Second Year ,2020 0202 المحاضر د.إيمان العيسوى Instructor Dr Eman Elesawy Lecture no .7 30th March 2020 Word Formation Processes/ Part 3 Aims: 1.To know word formation processes and their role in enriching language vocabulary 2.To be able to judge on the word-formation process used in creating words. Main Points Word-formation processes: Are specific techniques used by language users to add new vocabulary items to their language. These processes are similar between languages, still some languages might have other processes/resources than others. In this lecture we are going to discuss four of these processes, namely, derivation, reduplication and folk etymology. 1. What is derivation? When small bits, affixes, are added to a word. There are three types. Prefixes:added before the word, e.g. Mis-, un-, pre- Suffixes:added after the word, e.g.-less, -full, -ish, -ness (foolishness hence has two suffixes) Infixes:added in the middle of the word,e.g. -bloody-, -goddam- جامعة المنيا، كلية اﻷلسن ,Mini University, Faculty of Alsun علم الصرف ، الفرقة الثانية، Morphology , Second Year ,2020 0202 المحاضر د.إيمان العيسوى Instructor Dr Eman Elesawy 2. What is Reduplication: Reduplication is sometimes called rhyming compounds (subtype of compounds) These words are compounded from two rhyming words. Examples: lovey-dovey chiller-killer There are words that are formally very similar to rhyming compounds, but are not quite compounds in English because the second element is not really a word--it is just a nonsense item added to a root word to form a rhyme. -

Kenstowicz's "Paradigmatic Uniformity and Contrast"

Paradigmatic Uniformity and Contrast∗ Michael Kenstowicz Massachusetts Institute of Technology This paper reviews several cases where either the grammar strives to maintain the same output shape for pairs of inflected words that the regular phonology should otherwise drive apart (paradigmatic uniformity) or where the grammar strives to keep apart pairs of inflected words that the regular phonology threatens to merge (paradigmatic contrast). 1. Introduction The general research question which this paper addresses is the proper treatment of cases of opacity in which the triggering or blocking context for a phonological process is found in a paradigmatically related word. Chomsky & Halle's (1968) discussion of the minimal pair comp[´]nsation vs. cond[E]nsation is a classic example of the problem. In general, the contrast between a full vowel vs. schwa is predictable in English as a function of stress; but comp[´]nsation vs. ∗ An initial version of this paper was read at the Harvard-MIT Phonology 2000 Conference (May 1999); a later version was delivered at the 3èmes Journées Internationales du GDR Phonologie, University of Nantes (June 2001). I thank the editors as well as François Dell and Donca Steriade for helpful comments. 2 cond[E]nsation have the same σ` σ ´σ σ stress contour and thus raise the question whether English schwa is phonemic after all. SPE's insight was that the morphological bases from which these words are derived provide a solution to the problem: comp[´]nsate has a schwa while cond[E@]nse has a full stressed vowel. Chomsky and Halle's suggestion is that such paradigmatic relations among words can be described by embedding the derivation of one inside the derivation of the other. -

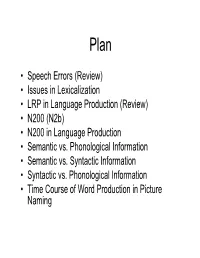

• Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic Vs

Plan • Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic vs. Phonological Information • Semantic vs. Syntactic Information • Syntactic vs. Phonological Information • Time Course of Word Production in Picture Naming Eech Sperrors • What can we learn from these things? • Anticipation Errors – a reading list Æ a leading list • Exchange Errors – fill the pool Æ fool the pill • Phonological, lexical, syntactic • Speech is planned in advance – Distance of exchange, anticipation errors suggestive of how far in advance we “plan” Word Substitutions & Word Blends • Semantic Substitutions • Lexicon is organized – That’s a horse of another color semantically AND Æ …a horse of another race phonologically • Phonological Substitutions • Word selection must happen – White Anglo-Saxon Protestant after the grammatical class of Æ …prostitute the target has been • Semantic Blends determined – Edited/annotated Æ editated – Nouns substitute for nouns; verbs for verbs • Phonological Blends – Substitutions don’t result in – Gin and tonic Æ gin and topic ungrammatical sentences • Double Blends – Arrested and prosecuted Æ arrested and persecuted Word Stem & Affix Morphemes •A New Yorker Æ A New Yorkan (American) • Seem to occur prior to lexical insertion • Morphological rules of word formation engaged during speech production Stranding Errors • Nouns & Verbs exchange, but inflectional and derivational morphemes rarely do – Rather, they are stranded • I don’t know that I’d -

Chapter 1 Typology of Complement Clauses Magdalena Lohninger University of Vienna Susi Wurmbrand University of Vienna

Chapter 1 Typology of Complement Clauses Magdalena Lohninger University of Vienna Susi Wurmbrand University of Vienna Put abstract here with \abstract. 1 Introduction—Universal questions about complement clauses Following Dixon (2010), complement clauses can be defined along several dimen- sions: they have the internal structure of a clause (i.e., a predicate-argument con- figuration); they function as a core argument of another predicate (the matrixor main predicate); they are restricted to a limited set of matrix predicates; and they describe semantic concepts such as propositions, facts, activities, states, events or situations (they cannot simply refer to a place or time). In this chapter we will follow this characterization and summarize major findings of clauses that “fill an argument slot in the structure of another clause” (Dixon (2010), 370). When looking at complement clauses typologically, one striking characteris- tic is found: despite extensive variation, there are restrictions of different sorts within and across languages, determined by the semantics of the matrix predi- cate, the semantics of the complement clause as well as the complement’s mor- phosyntactic properties. No language follows an “anything goes” strategy and the combination of matrix predicates and different types and meanings of com- plement clauses is often not free. However, these restrictions are not completely uniform. Cross-linguistically, the meaning of a complementation configuration is Change with \papernote Magdalena Lohninger & Susi Wurmbrand mapped -

153 Natasha Abner (University of Michigan)

Natasha Abner (University of Michigan) LSA40 Carlo Geraci (Ecole Normale Supérieure) Justine Mertz (University of Paris 7, Denis Diderot) Jessica Lettieri (Università degli studi di Torino) Shi Yu (Ecole Normale Supérieure) A handy approach to sign language relatedness We use coded phonetic features and quantitative methods to probe potential historical relationships among 24 sign languages. Lisa Abney (Northwestern State University of Louisiana) ANS16 Naming practices in alcohol and drug recovery centers, adult daycares, and nursing homes/retirement facilities: A continuation of research The construction of drug and alcohol treatment centers, adult daycare centers, and retirement facilities has increased dramatically in the United States in the last thirty years. In this research, eleven categories of names for drug/alcohol treatment facilities have been identified while eight categories have been identified for adult daycare centers. Ten categories have become apparent for nursing homes and assisted living facilities. These naming choices function as euphemisms in many cases, and in others, names reference morphemes which are perceived to reference a higher social class than competitor names. Rafael Abramovitz (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) P8 Itai Bassi (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Relativized Anaphor Agreement Effect The Anaphor Agreement Effect (AAE) is a generalization that anaphors do not trigger phi-agreement covarying with their binders (Rizzi 1990 et. seq.) Based on evidence from Koryak (Chukotko-Kamchan) anaphors, we argue that the AAE should be weakened and be stated as a generalization about person agreement only. We propose a theory of the weakened AAE, which combines a modification of Preminger (2019)'s AnaphP-encapsulation proposal as well as converging evidence from work on the internal syntax of pronouns (Harbour 2016, van Urk 2018). -

Lexicalization After Grammaticalization in the Development of Slovak Adjectives Ending In

Lexicalization after grammaticalization in the development of Slovak adjectives ending in -lý originating from l-participles Gabriela Múcsková, Comenius University and Slovak Academy of Sciences The paper deals with the development and current state of the Slovak participial forms, especially the participles with the formant -l- (the so-called l-participles) in the context of grammaticalization and lexicalization as complex and gradual changes. The analysis focuses on the group of “adjectives ending in -lý” as a result of “verb-to-adjective” lexicalization of former l-participles, which was conditioned by preceding grammaticalization of other members of the same participial paradigm. The group of lexemes identified in current Slovak descriptive grammatical and lexicographical works as “adjectives ending in -lý” is highly variable and includes a set of units of hybrid nature reflecting the overlapping of verbal and adjectival grammatical meanings and dynamic and static semantic components. Moreover, the group is rather limited, has irregular structural and derivational properties and is semantically rich, with extensive semantic derivation and polysemy. The characteristics of these units suggest a higher degree of their adjectivization, but the variability of the units reflects the different phases and degrees of this change, which was also influenced by language-planning factors in the Slovak historical context. Reconstruction of the phases of the adjectivization process, gradual decategorization and desemanticization, and reanalysis to a new structural and semantic class can serve as a contribution to more general questions about the nature of language change and its explanation. Keywords: participle, lexicalization, adjectivization, grammaticalization, lexicography 1. Introduction Linguistic descriptions of grammatical, word-formation and lexical structures are abstract reflexive constructs establishing boundaries between structural levels, parts of speech, categories and paradigms inside the language. -

Prosodic Morphology: Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction John J

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Linguistics Department Faculty Publication Series Linguistics January 1993 Prosodic Morphology: Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction John J. McCarthy University of Massachusetts, Amherst, [email protected] Alan Prince Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/linguist_faculty_pubs Part of the Morphology Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Phonetics and Phonology Commons Recommended Citation McCarthy, John J. and Prince, Alan, "Prosodic Morphology: Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction" (1993). Linguistics Department Faculty Publication Series. 14. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/linguist_faculty_pubs/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Linguistics at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics Department Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prosodic Morphology Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction John J. McCarthy Alan Prince University of Massachusetts, Amherst Rutgers University Copyright © 1993, 2001 by John J. McCarthy and Alan Prince. Permission is hereby granted by the authors to reproduce this document, in whole or in part, for personal use, for instruction, or for any other non-commercial purpose. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................... v Introduction to -

Space in Languages in Mexico and Central America Carolyn O'meara

Space in languages in Mexico and Central America Carolyn O’Meara, Gabriela Pérez Báez, Alyson Eggleston, Jürgen Bohnemeyer 1. Introduction This chapter presents an overview of the properties of spatial representations in languages of the region. The analyses presented here are based on data from 47 languages belonging to ten Deleted: on literature covering language families in addition to literature on language isolates. Overall, these languages are located primarily in Mexico, covering the Mesoamerican Sprachbundi, but also extending north to include languages such as the isolate Seri and several Uto-Aztecan languages, and south to include Sumu-Mayangna, a Misumalpan language of Nicaragua. Table 1 provides a list of the Deleted: The literature consulted includes a mix of languages analyzed for this chapter. descriptive grammars as well as studies dedicated to spatial language and cognition and, when possible and relevant, primary data collected by the authors. Table 1 provides a Table 1. Languages examined in this chapter1 Family / Stock Relevant sub-branches Language Mayan Yucatecan Yucatecan- Yucatec Lacandon Mopan-Itzá Mopan Greater Cholan Yokot’an (Chontal de Tabasco) Tseltalan Tseltalan Tseltal Zinacantán Tsotsil Q’anjob’alan- Q’anjob’alan Q’anjob’al Chujean Jacaltec Otomanguean Otopame- Otomí Eastern Highland Otomí Chinantecan Ixtenco Otomí San Ildefonso Tultepec Otomí Tilapa Otomí Chinantec Palantla Chinantec 1 In most cases, we have reproduced the language name as used in the studies that we cite. However, we diverge from this practice in a few cases. One such case would be one in which we know firsthand what the preferred language name is among members of the language community. -

Lightest to the Right: an Apparently Anomalous Displacement in Irish Ryan Bennett Emily Elfner James Mccloskey

Lightest to the Right: An Apparently Anomalous Displacement in Irish Ryan Bennett Emily Elfner James McCloskey This article analyzes mismatches between syntactic and prosodic con- stituency in Irish and attempts to understand those mismatches in terms of recent proposals about the nature of the syntax-prosody interface. It argues in particular that such mismatches are best understood in terms of Selkirk’s (2011) Match Theory, working in concert with con- straints concerned with rhythm and phonological balance. An appar- ently anomalous rightward movement that seems to target certain pronouns and shift them rightward is shown to be fundamentally a phonological process: a prosodic response to a prosodic dilemma. The article thereby adds to a growing body of evidence for the role of phonological factors in shaping constituent order. Keywords: syntax, prosody, VSO order, rightward movement, weak pronouns, prosodic displacement 1 Introduction What are the mechanisms that shape word order in natural language? A traditional and still widely favored answer to that question is that syntax has exclusive responsibility in this domain; in some traditions of investigation, in fact, syntax just is the study of word order. More recently the possibility has emerged, though, that word order is determined postsyntactically, in the process of what Berwick and Chomsky (2011) call ‘‘externalization’’—the translation of the hierarchical and recursive representations characteristic of syntax and semantics into the kinds of serial repre- sentations that the sensorimotor systems can manipulate. Given that overall conception, it is natural that some aspects of constituent order should be shaped by demands particular to phonology, and in recent years there have been many studies arguing for the role of phonology in shaping word The research reported on here has its origins in the meetings of the Prosody Interest Group at the University of California, Santa Cruz.