Lightest to the Right: an Apparently Anomalous Displacement in Irish Ryan Bennett Emily Elfner James Mccloskey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Donegal District Lunatic Asylum

‘A WORLD APART’ – The Donegal District Lunatic Asylum Number of Registrar Name Where Chargable This exhibition curated by the Donegal County Museum and the Archives Service, Donegal County Council in association with the HSE was inspired by the ending of the provision of residential mental health services at the St. Conal’s Hospital site. The hospital has been an integral part of Letterkenny and County Donegal for 154 years. Often shrouded by mythology and stigma, the asylum fulfilled a necessary role in society but one that is currently undergoing radical change.This exhibition, by putting into context the earliest history of mental health services in Donegal hopes to raise public awareness of mental health. The exhibition is organised in conjunction with Little John Nee’s artist’s residency in An Grianan Theatre and his performance of “The Mental”. This project is supported by PEACE III Programme managed for the Special EU Programmes Body by Donegal County Council. Timeline This Timeline covers the period of the reforms in the mental health laws. 1745 - Dean Jonathan Swift: 1907 - Eugenics Education Society: On his death he left money for the building of Saint Patrick’s This Society was established to promote population control Hospital (opened 1757), the first in Ireland to measures on undesirable genetic traits, including mental treat mental health patients. defects. 1774 - An Act for Regulating Private Madhouses: 1908 Report by Royal Commission This act ruled that there should be inspections of asylums once on Care of Feeble-Minded a year at least, but unfortunately, this only covered London. 1913 Mental Deficiency Act: 1800 - Pressure for reform is growing: This Act established the Board of Control to replace the Lunacy This is sparked off by the terrible conditions in London’s Commission. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

Barristers on Panel

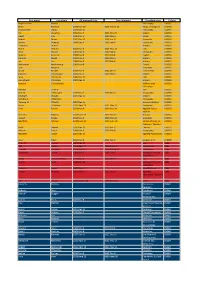

st Report Run Date: 21 Jun 2019 BARRISTERS ON PANEL The below list contains information on the number of payments* and the total amount paid to On Panel barristers for the period 1/07/18 – 31/12/18 Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments Buckley, Declan 417,945 52 McGrath, Imogen 43,604 15 Binchy, Michael 11,132 8 Fitzpatrick, Andrew 3,094 6 Egan, Emily 394,952 24 Boughton, David 43,480 86 Farrelly, Aoife 10,908 13 Fitzgerald, William 2,653 11 Hanratty, Patrick 385,932 11 Fleck, Kieran 43,142 7 Delaney, Michael Patrick 10,701 2 MacMahon, Noel A. 2,583 1 Halpin, Conor 337,833 26 Gayer, Sasha Louise 39,452 4 Lydon, Eileen 10,578 2 Roberts, Conor 2,030 3 O'Braonain, Luan 231,215 17 Ramsey, Michael 37,023 1 Hand, Derry 10,376 8 Cheatle, John 1,845 1 Kavanagh, James M. 187,198 6 Fahey, Grainne 36,678 73 Scully, Lorraine 9,696 6 Maher, Jeremy 1,538 2 Foley, Brian 181,914 20 McGuinness, Donal 29,223 5 Hogan, John 9,545 7 Keleher, Daniel 1,162 1 Woulfe, Donnchadh 179,160 9 Lowe, Robert 28,226 2 Walsh, Aidan 8,979 1 Hewson, Dermot G. 1,119 1 McCrann, Oonah 159,623 18 Barrington, Eileen 27,596 2 Kilfeather, Jonathan 8,642 4 Keane, Deirdre 1,076 4 McCullough, Eoin 143,268 14 White, Rory 27,032 14 Fleming, David 8,107 2 Danaher, Gerard 954 2 Corcoran, Sarah 139,707 104 Farren, Georgina 25,227 5 Tennyson, Lauren 7,679 3 Cullinane, Padraig J. -

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/Area

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/area College Roger Garrett Barden Philosophy CACSSS Brian Bocking 2015 Nov 15 2016 March 14 Study of Religions CACSSS Desmond M Clarke 2007 Dec 11 Philosophy CACSSS Pat Coughlan 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 English CACSSS David Cox 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Music CACSSS Robert Devoy 2011 Dec 13 2012 Jan 11 Geograhy CACSSS Francis Douglas 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Thomas J Dunne History CACSSS Maire Herbert 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 Irish CACSSS Aine Hyland 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Colbert Kearney 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 English CACSSS Dermot Keogh 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 History CACSSS Joe Lee 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 History CACSSS Mathew M MacNamara 2005 Nov 8 French CACSSS John Maguire Sociology CACSSS Grace Neville 2012 Nov 6 2012 Dec 6 French/T&L CACSSS Eamonn O Carragain 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 English CACSSS Sean O Coileain 2006 Dec 12 Irish CACSSS Donnchadh O Corrain 2007 Dec 11 History CACSSS Gearóid Ó Crualaoich Folklore and CACSSS Ethnology Padraig O Riain irish CACSSS Patrick O'Flanagan 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Geography CACSSS Elisabeth Okasha 2007 Dec 11 English CACSSS Brendan E O'Mahony Philosophy CACSSS Terence W O'Reilly 2007 Dec 11 Hispanic Studies CACSSS Denis O'Sullivan 2011 April 19 2011 May 11 Education CACSSS Fred Powell 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Applied Social CACSSS Studies Geoffrey Roberts 2017 June 13 2017 Dec 01 History CACSSS Joseph Ruane 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Sociology CACSSS Manfred Schewe 2019 June 11 2019 June 18 School of Lang, Lit, CACSSS -

Your Name Here

THE HISTORY OF THE FUTURE: MORPHOPHONOLOGY, SYNTAX, AND GRAMMATICALIZATION by LAMAR ASHLEY GRAHAM (Under the Direction of L. Chadwick Howe) ABSTRACT The appearance of new verbal paradigms in the Romance languages – namely, the synthetic future indicative and conditional paradigms – has been one of the hallmark studies within the field of grammaticalization. Already existing in Latin was a synthetic future indicative paradigm, with a full complement of endings. Many researchers (Garey 1955; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Slobbe 2004; among others) have agreed that the infinitive + HABĒRE construction was the genesis of Romance future paradigms, obviating and completely replacing the disfavored Latin synthetic future. However, even after Latin evolved into Spanish, there still existed a duality between a periphrastic, analytic future and a paradigmatic, synthetic future. Said duality implied several syntactic and morphophonological characteristics of Old and Classical Spanish, some of which are no longer extant in the modern language. Through an empirical study, employing variable rules analyses, of Old and Classical Spanish texts, it is shown that the synthetic and analytic future and conditional were not always fully complementary of another, as the synthetic began to be used in contexts customarily reserved for the analytic construction. Within this work it will be shown how morphophonological and syntactic properties necessitated the existence of the analytic construction, especially the status of the auxiliary-turned-affix-turned- inflectional ending haber. Also of interest will be the manner in which the future and conditional paradigms derived syntactically in Old and Classical Spanish, with special attention lent to the role of cliticization principles in their structure. -

Lecture No .7 30Th March 2020 Word Formation Processes

جامعة المنيا، كلية اﻷلسن ,Mini University, Faculty of Alsun علم الصرف ، الفرقة الثانية، Morphology , Second Year ,2020 0202 المحاضر د.إيمان العيسوى Instructor Dr Eman Elesawy Lecture no .7 30th March 2020 Word Formation Processes/ Part 3 Aims: 1.To know word formation processes and their role in enriching language vocabulary 2.To be able to judge on the word-formation process used in creating words. Main Points Word-formation processes: Are specific techniques used by language users to add new vocabulary items to their language. These processes are similar between languages, still some languages might have other processes/resources than others. In this lecture we are going to discuss four of these processes, namely, derivation, reduplication and folk etymology. 1. What is derivation? When small bits, affixes, are added to a word. There are three types. Prefixes:added before the word, e.g. Mis-, un-, pre- Suffixes:added after the word, e.g.-less, -full, -ish, -ness (foolishness hence has two suffixes) Infixes:added in the middle of the word,e.g. -bloody-, -goddam- جامعة المنيا، كلية اﻷلسن ,Mini University, Faculty of Alsun علم الصرف ، الفرقة الثانية، Morphology , Second Year ,2020 0202 المحاضر د.إيمان العيسوى Instructor Dr Eman Elesawy 2. What is Reduplication: Reduplication is sometimes called rhyming compounds (subtype of compounds) These words are compounded from two rhyming words. Examples: lovey-dovey chiller-killer There are words that are formally very similar to rhyming compounds, but are not quite compounds in English because the second element is not really a word--it is just a nonsense item added to a root word to form a rhyme. -

Kenstowicz's "Paradigmatic Uniformity and Contrast"

Paradigmatic Uniformity and Contrast∗ Michael Kenstowicz Massachusetts Institute of Technology This paper reviews several cases where either the grammar strives to maintain the same output shape for pairs of inflected words that the regular phonology should otherwise drive apart (paradigmatic uniformity) or where the grammar strives to keep apart pairs of inflected words that the regular phonology threatens to merge (paradigmatic contrast). 1. Introduction The general research question which this paper addresses is the proper treatment of cases of opacity in which the triggering or blocking context for a phonological process is found in a paradigmatically related word. Chomsky & Halle's (1968) discussion of the minimal pair comp[´]nsation vs. cond[E]nsation is a classic example of the problem. In general, the contrast between a full vowel vs. schwa is predictable in English as a function of stress; but comp[´]nsation vs. ∗ An initial version of this paper was read at the Harvard-MIT Phonology 2000 Conference (May 1999); a later version was delivered at the 3èmes Journées Internationales du GDR Phonologie, University of Nantes (June 2001). I thank the editors as well as François Dell and Donca Steriade for helpful comments. 2 cond[E]nsation have the same σ` σ ´σ σ stress contour and thus raise the question whether English schwa is phonemic after all. SPE's insight was that the morphological bases from which these words are derived provide a solution to the problem: comp[´]nsate has a schwa while cond[E@]nse has a full stressed vowel. Chomsky and Halle's suggestion is that such paradigmatic relations among words can be described by embedding the derivation of one inside the derivation of the other. -

View: Journal of Flann O’Brien Studies 4.1

The Bildung Subject & Modernist Autobiography in An Béal Bocht (Beyond An tOileánach) Brian Ó Conchubhair University of Notre Dame The Irish Bildungsroman, because it employs the defamiliarising techniques of parody and mimicry, thus functions like the radical modern art that Theodor Adorno describes, which is hated ‘because it reminds us of missed chances, but also because by its sheer existence it reveals the dubiousness of the heteronomous structural ideal.’1 An Béal Bocht can be, and usually is, read as a parody of 20th-century Irish language texts. But it is, in equal measure, an homage to them and an appropriation of their stylistic conventions, motifs, and attitudes. The novel’s building blocks were assuredly those cannibalised texts, and from them O’Nolan creates a dissonant, hyperreal, but easily recognisable world. No less fundamental, however, is an outdated, hyper- masculine sense of Irishness and a fabricated sense of the cultural nationalist-inspired depiction of lived Gaeltacht experience. This mocking, ironic book is driven by vitriolic enmity to any external prescriptive account of Gaeltacht life and any attempt to stereotype or generalise Irish speakers’ experience. As Joseph Brooker observes, its ‘greatest significance is not as a rewriting of a particular book, but rather a reinscription of a genre.’2 As a synthesis of literary conceits, cultural motifs, and nationalist tropes, it marks a cultural moment in Irish literary and cultural history. It remains undimmed by the passage of time, but for all its allusions, parodies, and references, it continues to amuse, entertain, and instruct global readers with little or no Irish, as well as those with even less awareness of the texts from which An Béal Bocht is drawn. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

Prosodic Morphology: Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction John J

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Linguistics Department Faculty Publication Series Linguistics January 1993 Prosodic Morphology: Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction John J. McCarthy University of Massachusetts, Amherst, [email protected] Alan Prince Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/linguist_faculty_pubs Part of the Morphology Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Phonetics and Phonology Commons Recommended Citation McCarthy, John J. and Prince, Alan, "Prosodic Morphology: Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction" (1993). Linguistics Department Faculty Publication Series. 14. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/linguist_faculty_pubs/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Linguistics at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics Department Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prosodic Morphology Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction John J. McCarthy Alan Prince University of Massachusetts, Amherst Rutgers University Copyright © 1993, 2001 by John J. McCarthy and Alan Prince. Permission is hereby granted by the authors to reproduce this document, in whole or in part, for personal use, for instruction, or for any other non-commercial purpose. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................... v Introduction to -

1 FIONN in HELL an Anonymous Early Sixteenth-Century Poem In

1 FIONN IN HELL An anonymous early sixteenth-century poem in Scots describes Fionn mac Cumhaill as having ‘dang þe devill and gart him ʒowle’ (‘struck the Devil and made him yowl’) (Fisher 1999: 36). The poem is known as ‘The Crying of Ane Play.’ Scots literature of the late medieval and early modern period often shows a garbled knowledge of Highland culture; commonly portraying Gaels and their language and traditions negatively. Martin MacGregor notes that Lowland satire of Highlanders can, ‘presuppose some degree of understanding of the language, and of attendant cultural and social practices’ (MacGregor 2007: 32). Indeed Fionn and his band of warriors, 1 collectively Na Fiantaichean or An Fhèinn0F in modern Scottish Gaelic, are mentioned a number of times in Lowland literature of the period (MacKillop 1986: 72-74). This article seeks to investigate the fate of Fionn’s soul in late medieval and early modern Gaelic literature, both Irish and Scottish. This is done only in part to consider if the yowling Devil and his encounter with Fionn from the ‘The Crying of Ane Play’ might represent something recognizable from contemporaneous Gaelic literature. Our yowling Devil acts here as something of a prompt for an investigation of Fionn’s potential salvation or damnation in a number of sixteenth-century, and earlier, Gaelic ballads. The monumental late twelfth- or early thirteenth-century (Dooley 2004) text Acallam na 2 Senórach (‘The Colloquy of the Ancients’) will also be considered here.1F Firstly, the Scots poem must be briefly investigated in order to determine its understanding of Gaelic conventions. -

Ansteorran College of Heralds Does Estrill Swet, Retiarius Pursuivant, Make Greetings

Here are the decisions about ILoI0009 made on December 9, 2000 (AS XXXV) at Stargate Yule Revel, as typed by Kathri (who has corrected the item headers where Bordure needed it, which explains why some of the comments seem to be about problems that don't exist.) Griffon, Bordure (and deputy-Asterisk-for-the-day) Unto the Ansteorran College of Heralds does Estrill Swet, Retiarius Pursuivant, make greetings. For information on commentary submission formats or to receive a copy of the collated commentary, you can contact me at: Deborah Sweet 824 E 8th, Stillwater, OK 74074 405/624-9344 (before 10pm) [email protected] Commenters for this issue: Magnus von Lübeck - Raven's Fort. All items were checked against the on-line O&A. Mari Elspeth nic Bryan - Solveig Throndardottir, Name Construction in Mediaeval Japan, Free Trumpet Studies in Heraldry & Onomastics 87 (Albuquerque, NM: The Outlaw Press, 1994). Andrew W. Nelson, The Compact Nelson Japanese-English Character Dictionary, abridged by John H. Haig. (Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1999). The documentation for a number of the name submissions in this ILoI is not presented in enough detail to be reviewed by the College of Arms without problems. It is not simply enough to (for example) state that a name is in Withycombe. Even "Withycombe, page (page #)" is not enough. Different editions of Withycombe have the headers on different pages. Even the 3rd edition hardback has entries on different pages than the 3rd edition paperback. Name documentation has to be summarized clearly and completely enough that: 1) a commenter can quickly and easily look up the reference and 2) it is clear why this reference supports the registration of the submitted name In a number of the comments below, I refer to the Annals of Connacht.