UCD Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loughs Carra, Mask and Corrib; Resources, Borders and Passageways

Loughs Carra, Mask and Corrib; resources, borders and passageways A National Heritage Week 2020 Project by the Joyce Country and Western Lakes Heritage Network Introduction: Loughs Carra, Mask and Corrib are all connected with all their waters draining into the Atlantic Ocean. Their origins lie in the surrounding bedrock and the moving ice that dominated the Irish landscape. Today they are landscape icons, angling paradise and drinking water reservoirs but they have also shaped the communities on their shores. This project, the first of the Joyce Country and Western Lakes Heritage Network, explores the relationships that the people from the local towns and villages have had with these lakes, how they were perceived, how they were used and how they have been embedded in their history. The project consists of a series of short articles on various subjects that were composed by heritage officers of the local community councils and members of the local historical societies. They will dwell on the geological origin of the lakes, evidence of the first people living on their shores, local traditions and historical events and the inspiration that they offered to artists over the years. These articles are collated in this document for online publication on the Joyce Country and Western Lakes Geopark Project website (www.joycecountrygeoparkproject.ie) as well as on the website of the various heritage societies and initiatives of the local communities. Individual articles – some bilingual as a large part of the area is in the Gaeltacht – will be shared over social media on a daily basis for the duration of National Heritage Week. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

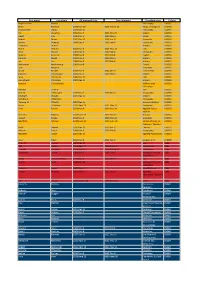

Barristers on Panel

st Report Run Date: 21 Jun 2019 BARRISTERS ON PANEL The below list contains information on the number of payments* and the total amount paid to On Panel barristers for the period 1/07/18 – 31/12/18 Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments Buckley, Declan 417,945 52 McGrath, Imogen 43,604 15 Binchy, Michael 11,132 8 Fitzpatrick, Andrew 3,094 6 Egan, Emily 394,952 24 Boughton, David 43,480 86 Farrelly, Aoife 10,908 13 Fitzgerald, William 2,653 11 Hanratty, Patrick 385,932 11 Fleck, Kieran 43,142 7 Delaney, Michael Patrick 10,701 2 MacMahon, Noel A. 2,583 1 Halpin, Conor 337,833 26 Gayer, Sasha Louise 39,452 4 Lydon, Eileen 10,578 2 Roberts, Conor 2,030 3 O'Braonain, Luan 231,215 17 Ramsey, Michael 37,023 1 Hand, Derry 10,376 8 Cheatle, John 1,845 1 Kavanagh, James M. 187,198 6 Fahey, Grainne 36,678 73 Scully, Lorraine 9,696 6 Maher, Jeremy 1,538 2 Foley, Brian 181,914 20 McGuinness, Donal 29,223 5 Hogan, John 9,545 7 Keleher, Daniel 1,162 1 Woulfe, Donnchadh 179,160 9 Lowe, Robert 28,226 2 Walsh, Aidan 8,979 1 Hewson, Dermot G. 1,119 1 McCrann, Oonah 159,623 18 Barrington, Eileen 27,596 2 Kilfeather, Jonathan 8,642 4 Keane, Deirdre 1,076 4 McCullough, Eoin 143,268 14 White, Rory 27,032 14 Fleming, David 8,107 2 Danaher, Gerard 954 2 Corcoran, Sarah 139,707 104 Farren, Georgina 25,227 5 Tennyson, Lauren 7,679 3 Cullinane, Padraig J. -

History of the Mackenzies Alexander Mackenzie

History Of The Mackenzies Alexander Mackenzie THE HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES. ORIGIN. THE CLAN MACKENZIE at one time formed one of the most powerful families in the Highlands. It is still one of the most numerous and influential, and justly claims a very ancient descent. But there has always been a difference of opinion regarding its original progenitor. It has long been maintained and generally accepted that the Mackenzies are descended from an Irishman named Colin or Cailean Fitzgerald, who is alleged but not proved to have been descended from a certain Otho, who accompanied William the Conqueror to England, fought with that warrior at the battle of Hastings, and was by him created Baron and Castellan of Windsor for his services on that occasion. THE REPUTED FITZGERALD DESCENT. According to the supporters of the Fitzgerald-Irish origin of the clan, Otho had a son Fitz-Otho, who is on record as his father's successor as Castellan of Windsor in 1078. Fitz-Otho is said to have had three sons. Gerald, the eldest, under the name of Fitz- Walter, is said to have married, in 1112, Nesta, daughter of a Prince of South Wales, by whom he also had three sons. Fitz-Walter's eldest son, Maurice, succeeded his father, and accompanied Richard Strongbow to Ireland in 1170. He was afterwards created Baron of Wicklow and Naas Offelim of the territory of the Macleans for distinguished services rendered in the subjugation of that country, by Henry II., who on his return to England in 1172 left Maurice in the joint Government. -

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/Area

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/area College Roger Garrett Barden Philosophy CACSSS Brian Bocking 2015 Nov 15 2016 March 14 Study of Religions CACSSS Desmond M Clarke 2007 Dec 11 Philosophy CACSSS Pat Coughlan 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 English CACSSS David Cox 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Music CACSSS Robert Devoy 2011 Dec 13 2012 Jan 11 Geograhy CACSSS Francis Douglas 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Thomas J Dunne History CACSSS Maire Herbert 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 Irish CACSSS Aine Hyland 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Colbert Kearney 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 English CACSSS Dermot Keogh 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 History CACSSS Joe Lee 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 History CACSSS Mathew M MacNamara 2005 Nov 8 French CACSSS John Maguire Sociology CACSSS Grace Neville 2012 Nov 6 2012 Dec 6 French/T&L CACSSS Eamonn O Carragain 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 English CACSSS Sean O Coileain 2006 Dec 12 Irish CACSSS Donnchadh O Corrain 2007 Dec 11 History CACSSS Gearóid Ó Crualaoich Folklore and CACSSS Ethnology Padraig O Riain irish CACSSS Patrick O'Flanagan 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Geography CACSSS Elisabeth Okasha 2007 Dec 11 English CACSSS Brendan E O'Mahony Philosophy CACSSS Terence W O'Reilly 2007 Dec 11 Hispanic Studies CACSSS Denis O'Sullivan 2011 April 19 2011 May 11 Education CACSSS Fred Powell 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Applied Social CACSSS Studies Geoffrey Roberts 2017 June 13 2017 Dec 01 History CACSSS Joseph Ruane 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Sociology CACSSS Manfred Schewe 2019 June 11 2019 June 18 School of Lang, Lit, CACSSS -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

What's in an Irish Name?

What’s in an Irish Name? A Study of the Personal Naming Systems of Irish and Irish English Liam Mac Mathúna (St Patrick’s College, Dublin) 1. Introduction: The Irish Patronymic System Prior to 1600 While the history of Irish personal names displays general similarities with the fortunes of the country’s place-names, it also shows significant differences, as both first and second names are closely bound up with the ego-identity of those to whom they belong.1 This paper examines how the indigenous system of Gaelic personal names was moulded to the requirements of a foreign, English-medium administration, and how the early twentieth-century cultural revival prompted the re-establish- ment of an Irish-language nomenclature. It sets out the native Irish system of surnames, which distinguishes formally between male and female (married/ un- married) and shows how this was assimilated into the very different English sys- tem, where one surname is applied to all. A distinguishing feature of nomen- clature in Ireland today is the phenomenon of dual Irish and English language naming, with most individuals accepting that there are two versions of their na- me. The uneasy relationship between these two versions, on the fault-line of lan- guage contact, as it were, is also examined. Thus, the paper demonstrates that personal names, at once the pivots of individual and group identity, are a rich source of continuing insight into the dynamics of Irish and English language contact in Ireland. Irish personal names have a long history. Many of the earliest records of Irish are preserved on standing stones incised with the strokes and dots of ogam, a 1 See the paper given at the Celtic Englishes II Colloquium on the theme of “Toponyms across Languages: The Role of Toponymy in Ireland’s Language Shifts” (Mac Mathúna 2000). -

Ireland Under the Normans Goddard Henry Orpen

The Sub-Infeudation Of Connaught 1237 And Afterwards Ireland Under The Normans 1169-1216 By Goddard Henry Orpen LATE SCHOLAR OF TRINITY COLLEGE,DUBLIN EDITOR OF 'THE SONG OF DERMOT AND THE EARL ' MEMBER OF THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY 1911 Richard de Burgh had now a free hand in Connaught, and though sundry attempts at occupation had been made at various times since the beginning of the century, the effective settlement of Anglo- Normans in the province may be said to have commenced in 1237. In that year, says the Irish annalist, ‘ the barons of Erin came and commenced to build castles in it’. In the following year ‘ castles were erected in Muinter Murchada (the northern half of the barony of Clare, County Galway), Conmaicne Cuile (the barony of Kilmaine, south of the river Robe, County Mayo), and in Cera (the barony of Carra, County Mayo) by the aforesaid barons’. [1] Save for personal quarrels among the O’Conors themselves the peace was unbroken. Unfortunately there is no contemporary summary of Richard de Burgh’s enfeoffments, such as the Song of Dermot gives of those of Strongbow and the elder Hugh de Lacy, and though there trans- cripts in the ‘ Red Book of the Earl of Kildare’ and in the ‘ Gormanston Register’ of several charters of this period, we are largely dependent on indications in the annals, and on inferences from later documents and records for our knowledge of the Anglo-Norman settlement in Connaught. Indeed the first comprehensive account is to be gleaned from the Inquisitions taken in 1333 [2] after the murder of William de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, fifteen years after the great disruption caused by the Scottish invasion under Edward Bruce, and at a time when the royal power in Ireland had begun to wax faint. -

Poems of Oisin, Bard of Erin : "The Battle of Ventry Harbour," &C. from the Irish

/l,í / ^ i-^^ 9 POEMS OF OISIN, ETC. fnms OISIN, BAED OF EEIN. '* THE BATTLE OF YENTEY HAEBOUE," &c. Emm i\^ S^rfeij. BY JOHN HAWKINS SIMPSON. AUTHOR OF " AN ENGLISHMAN'S TESTIMONY TO THE URGENT NECESSITY FOR A TENANT RIGHT BILL FOR IRELAND." LONDON: BOSWOPtTH & HAPRÍSON, 21.% REGENT STREET. EDINBURGH : JOHN MENZIES. DUBLIN: M'GLASHAN AND GILL. 1857. [The Right of Transkition is reserved.] LONDOM : Printed bv 04, J. Paljiek. 27, Lamb's Conduit Street. PEEFACE, Mr. John Mac Faden, a highly intelligent young farmer in Mayo, and Mr. James O'Sul- LiVAN, a native of the county Kerry, have greatly aided me in the translation of these ancient poems ; to each of them I take this opportunity of tendering my -svarmest thanks for their kind assistance. There are many in Ireland ^Yho could ])roduce far better works on the poems of Oisin, and it is to be hoped that some of them will, ere long, give to the public good translations of the old and beautiful literature of their native land. VI PREFACE. I shall esteem it a great favour on the part of any one who will famish me with corrections of this little volume, or with materials for additional notes, explanatory of the Fenian Heroes and their exploits ; and shall gratefully acknowledge any contributions towards another work, should this be deemed worthy a successor. J. H. S. London, Oct. 2Sth, 1857. CONTENTS. PAGE Preface ...... v OlSIN, BARD OF ErIN ..... 1 Deardra . .12 conloch, son of cuthullin . .24 The Fenii of Erin and Fionn Mac Cumhal . 31 Dialogue between Oisin and St. -

Heineman Royal Ancestors Medieval Europe

HERALDRYand BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE HERALDRY and BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE INTRODUCTION After producing numerous editions and revisions of the Another way in which the royal house of a given country familiy genealogy report and subsequent support may change is when a foreign prince is invited to fill a documents the lineage to numerous royal ancestors of vacant throne or a next-of-kin from a foreign house Europe although evident to me as the author was not clear succeeds. This occurred with the death of childless Queen to the readers. The family journal format used in the Anne of the House of Stuart: she was succeeded by a reports, while comprehensive and the most popular form prince of the House of Hanover who was her nearest for publishing genealogy can be confusing to individuals Protestant relative. wishing to trace a direct ancestral line of descent. Not everyone wants a report encumbered with the names of Unlike all Europeans, most of the world's Royal Families every child born to the most distant of family lines. do not really have family names and those that have adopted them rarely use them. They are referred to A Royal House or Dynasty is a sort of family name used instead by their titles, often related to an area ruled or by royalty. It generally represents the members of a family once ruled by that family. The name of a Royal House is in various senior and junior or cadet branches, who are not a surname; it just a convenient way of dynastic loosely related but not necessarily of the same immediate identification of individuals. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

A Defense of the 63Rd New York State Volunteer Regiment of the Irish Brigade Patricia Vaticano

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-2008 A defense of the 63rd New York State Volunteer Regiment of the Irish Brigade Patricia Vaticano Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Vaticano, Patricia, "A defense of the 63rd New York State Volunteer Regiment of the Irish Brigade" (2008). Master's Theses. Paper 703. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DEFENSE OF THE 63RD NEW YORK STATE VOLUNTEER REGIMENT OF THE IRISH BRIGADE By PATRICIA VATICANO Master of Arts in History University of Richmond 2008 Dr. Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director During the American Civil War, New York State’s irrepressible Irish Brigade was alternately composed of a number of infantry regiments hailing both from within New York City and from within and without the state, not all of them Irish, or even predominantly so. The Brigade’s core structure, however, remained constant throughout the war years and consisted of three all-Irish volunteer regiments with names corresponding to fighting units made famous in the annuals of Ireland’s history: the 69th, the 88th, and the 63rd. The 69th, or Fighting 69th, having won praise and homage for its actions at First Bull Run, was designated the First Regiment of the Brigade and went on to even greater glory in the Civil War and every American war thereafter.