The Durbin Amendment's Interchange Fee and Network Non-Exclusivity Provisions: Did the Federal Reserve Board Overstep Its Boundaries Kathleen A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic Fund Transfers Your Rights

ELECTRONIC FUND TRANSFERS YOUR RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES Indicated below are types of Electronic Fund Transfers we are capable of handling, some of which may not apply to your account. Please read this disclosure carefully because it tells you your rights and obligations for the transactions listed. You should keep this notice for future reference. Electronic Fund Transfers Initiated By Third Parties. You may authorize a third party to initiate electronic fund transfers between your account and the third party’s account. These transfers to make or receive payment may be one-time occurrences or may recur as directed by you. These transfers may use the Automated Clearing House (ACH) or other payments network. Your authorization to the third party to make these transfers can occur in a number of ways. For example, your authorization to convert a check to an electronic fund transfer or to electronically pay a returned check charge can occur when a merchant provides you with notice and you go forward with the transaction (typically, at the point of purchase, a merchant will post a sign and print the notice on a receipt). In all cases, these third party transfers will require you to provide the third party with your account number and bank information. This information can be found on your check as well as on a deposit or withdrawal slip. Thus, you should only provide your bank and account information (whether over the phone, the Internet, or via some other method) to trusted third parties whom you have authorized to initiate these electronic fund transfers. -

Authorisation Service Sales Sheet Download

Authorisation Service OmniPay is First Data’s™ cost effective, Supported business profiles industry-leading payment processing platform. In addition to card present POS processing, the OmniPay platform Authorisation Service also supports these transaction The OmniPay platform Authorisation Service gives you types and products: 24/7 secure authorisation switching for both domestic and international merchants on behalf of merchant acquirers. • Card Present EMV offline PIN • Card Present EMV online PIN Card brand support • Card Not Present – MOTO The Authorisation Service supports a wide range of payment products including: • Dynamic Currency Conversion • Visa • eCommerce • Mastercard • Secure eCommerce –MasterCard SecureCode, Verified by Visa and SecurePlus • Maestro • Purchase with Cashback • Union Pay • SecureCode for telephone orders • JCB • MasterCard Gaming (Payment of winnings) • Diners Card International • Address Verification Service • Discover • Recurring and Installment • BCMC • Hotel Gratuity • Unattended Petrol • Aggregator • Maestro Advanced Registration Program (MARP) Supported authorisation message protocols • OmniPay ISO8583 • APACS 70 Authorisation Service Connectivity to the Card Schemes OmniPay Authorisation Server Resilience Visa – Each Data Centre has either two or four Visa EAS servers and resilient connectivity to Visa Europe, Visa US, Visa Canada, Visa CEMEA and Visa AP. Mastercard – Each Data Centre has a dedicated Mastercard MIP and resilient connectivity to the Mastercard MIP in the other Data Centre. The OmniPay platform has connections to Banknet for both European and non-European authorisations. Diners/Discover – Each Data Centre has connectivity to Diners Club International which is also used to process Discover Card authorisations. JCB – Each Data Centre has connectivity to Japan Credit Bureau which is used to process JCB authorisations. UnionPay – Each Data Centre has connectivity to UnionPay International which is used to process UnionPay authorisations. -

New Debit Card Solutions At

New Debit Card Solutions Debit Mastercard and Visa Debit are ready Swiss Banking Services Forum, 22 May 2019 Philippe Eschenmoser, Head Cards & A2A, Swisskey Ltd Maestro/V PAY Have Established Themselves As the “Key to the Account” – Schemes, However, Are Forcing Market Entry For Successor Products Response from the Maestro and V PAY are successful… …but are not future-capable products schemes # cards Maestro V PAY on Lower earnings potential millions8 for issuers as an alternative payment traffic products (e.g. 6 credit cards, TWINT) Issuer 4 V PAY will be 2 decommissioned by VISA Functional limitations: in 20211 – Visa Debit as 0 • No e-commerce the successor 2000 2018 • No preauthorizations Security and stability have End- • No virtualization proven themselves customer High acceptance in CH and Merchants with an online MasterCard is positioning abroad in Europe offer are demanding an DMC in the medium term online-capable debit as the successor to Standard product with an Merchan product Maestro integrated bank card t 2 1: As of 2021 no new V PAY may be issued TWINT (Still) No Substitute For Debit Cards – Credit Cards With Divergent Market Perception TWINT (still) not alternative for debit Credit cards a no alternative for debit Lacking a bank card Debit function Limited target group (age, ~1.1 M 1 ~10 M. creditworthiness...) Issuer ~48.5 k ~170 k1 No direct account debiting DMC/ Visa Debit Potentially high annual fee End-customer Lower customer penetration Banks and merchants DMC/ P2P demand an online- Higher costs Merchant Visa Debit -

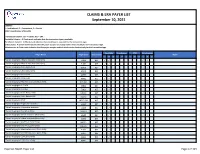

Claims and Remits Payer List

CLAIMS & ERA PAYER LIST September 10, 2021 LEGEND: I = Institutional, P = Professional, D = Dental COB = Coordination of Benefits Transaction Column: 837 = Claims, 835 = ERA Available Column: A Check-mark indicates that the transaction type is available. Enrollment Column: A Check-mark indicates that enrollment is required for the transaction type. COB Column: A Check-mark Indicates that the payer accepts secondary claims electronically for the transaction type. Attachments: A Check-mark indicates that the payer accepts medical attachments electronically for the transaction type. Available Enrollment COB Attachments Payer Name Payer Code Transaction Notes I P D I P D I P D I P D *Carisk Imaging to Allstate Insurance (Auto Only) E1069 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Allstate Insurance (Auto Only) E1069 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Geico (Auto Only) GEICO 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Geico (Auto Only) GEICO 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Nationwide A0002 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Nationwide A0002 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to New York City Law Department NYCL001 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to NJ-PLIGA E3926 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to NJ-PLIGA E3926 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to North Dakota WSI NDWSI 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to North Dakota WSI NDWSI 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to NYSIF NYSIF1510 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Progressive Insurance E1139 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Progressive Insurance E1139 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Pure (Auto Only) PURE01 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Safeco Insurance (Auto Only) E0602 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ -

2020 Annual Report Discover Card • $71 Billion in Loans a Leading • Leading Cash Rewards Program

2020 Annual Report Discover Card • $71 billion in loans A Leading • Leading cash rewards program Student Loans Digital Bank • $10 billion in student loans and Payments • Offered at more than 2,400 colleges Personal Loans • $7 billion in loans • Debt consolidation and major purchases Partner Home Loans • $2 billion in mortgages Discover is one of the largest digital banks in the United • Cash-out refinance and home loans States, offering a broad array of products, including credit cards, personal loans, student loans, deposit products Deposit Products and home loans. • $63 billion in direct-to-consumer deposits • Money market accounts, certificates The Discover brand is known for rewards, service and of deposit, savings accounts and checking value. Across all digital banking products, Discover seeks accounts to help customers meet their financial needs and achieve brighter financial futures. Discover Network Discover Global Network, the global payments brand of • $181 billion volume Discover Financial Services, strives to be the most flexible • 20+ network alliances and innovative payments partner in the United States and around the world. Our Network Partners business provides payment transaction processing and settlement services PULSE Debit Network on the Discover Network. PULSE is one of the nation’s • $212 billion volume leading ATM/debit networks, and Diners Club International is a global payments network with acceptance around Diners Club International the world. • $24 billion volume To my fellow shareholders, A year has passed since our world changed virtually overnight as we faced the greatest public health crisis in a century and the resulting economic contraction. We remain grateful to those on the front lines of this battle, including healthcare and emergency workers, and everyone who has taken personal risk to make sure the essential services of our society keep running. -

Submission to the Reserve Bank of Australia Response to EFTPOS

Submission to the Reserve Bank of Australia Response To EFTPOS Industry Working Group By The Australian Retailers Association 13 September 2002 Response To EFTPOS Industry Working Group Prepared with the assistance of TransAction Resources Pty Ltd Australian Retailers Association 2 Response To EFTPOS Industry Working Group Contents 1. Executive Summary.........................................................................................................4 2. Introduction......................................................................................................................5 2.1 The Australian Retailers Association ......................................................................5 3. Objectives .......................................................................................................................5 4. Process & Scope.............................................................................................................6 4.1 EFTPOS Industry Working Group – Composition ...................................................6 4.2 Scope Of Discussion & Analysis.............................................................................8 4.3 Methodology & Review Timeframe.........................................................................9 5. The Differences Between Debit & Credit .......................................................................10 5.1 PIN Based Transactions.......................................................................................12 5.2 Cash Back............................................................................................................12 -

The Transaction Network in Japan's Interbank Money Markets

The Transaction Network in Japan’s Interbank Money Markets Kei Imakubo and Yutaka Soejima Interbank payment and settlement flows have changed substantially in the last decade. This paper applies social network analysis to settlement data from the Bank of Japan Financial Network System (BOJ-NET) to examine the structure of transactions in the interbank money market. We find that interbank payment flows have changed from a star-shaped network with money brokers mediating at the hub to a decentralized network with nu- merous other channels. We note that this decentralized network includes a core network composed of several financial subsectors, in which these core nodes serve as hubs for nodes in the peripheral sub-networks. This structure connects all nodes in the network within two to three steps of links. The network has a variegated structure, with some clusters of in- stitutions on the periphery, and some institutions having strong links with the core and others having weak links. The structure of the network is a critical determinant of systemic risk, because the mechanism in which liquidity shocks are propagated to the entire interbank market, or like- wise absorbed in the process of propagation, depends greatly on network topology. Shock simulation examines the propagation process using the settlement data. Keywords: Interbank market; Real-time gross settlement; Network; Small world; Core and periphery; Systemic risk JEL Classification: E58, G14, G21, L14 Kei Imakubo: Financial Systems and Bank Examination Department, Bank of Japan (E-mail: [email protected]) Yutaka Soejima: Payment and Settlement Systems Department, Bank of Japan (E-mail: [email protected]) Empirical work in this paper was prepared for the 2006 Financial System Report (Bank of Japan [2006]), when the Bank of Japan (BOJ) ended the quantitative easing policy. -

The Topology of Interbank Payment Flows

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports The Topology of Interbank Payment Flows Kimmo Soramäki Morten L. Bech Jeffrey Arnold Robert J. Glass Walter E. Beyeler Staff Report no. 243 March 2006 This paper presents preliminary findings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily reflective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. The Topology of Interbank Payment Flows Kimmo Soramäki, Morten L. Bech, Jeffrey Arnold, Robert J. Glass, and Walter E. Beyeler Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 243 March 2006 JEL classification: E59, E58, G1 Abstract We explore the network topology of the interbank payments transferred between commercial banks over the Fedwire® Funds Service. We find that the network is compact despite low connectivity. The network includes a tightly connected core of money-center banks to which all other banks connect. The degree distribution is scale-free over a substantial range. We find that the properties of the network changed considerably in the immediate aftermath of the attacks of September 11, 2001. Key words: network, topology, interbank, payment, Fedwire, September 11, 2001 Soramäki: Helsinki University of Technology. Bech: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Arnold: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Glass: Sandia National Laboratories. Beyeler: Sandia National Laboratories. Address correspondence to Morten L. Bech (e-mail: [email protected]). -

DEBIT CARD POLICY 1. Debit Card a Debit Card Is a Plastic Card That

DEBIT CARD POLICY 1. Debit Card A debit card is a plastic card that provides the cardholder electronic access to his/her bank account(s). It is an instrument that can be used to: Avail of banking services such as cash withdrawal, balance enquiry etc., from any ATM and Micro ATM. Make payments to merchants against purchase, withdrawal of cash at POS or both within the prescribed limit by RBI at merchant outlets. e-Commerce transactions. 2. Understanding a Debit Card. a) Card Number: It is a 16 or 19 digit number linked to customer’s bank account. First 6 digits represent Bank’s identification no., next 4 digits represent Branch Sol ID. Remaining digits indicates serial number of the cards issued by that particular branch. Currently Bank issue debit cards with 16 digit length. b) Name of the Person: Person authorized to use the card. This field is present only on personalized card. c) Valid Date: It is in mm/yy format. The card is valid till the last day of the month. d) Card Verification Value (CVV) /CVV2: A 03 (Three) digit number printed on the back side of every debit card. This is used for validation of online transactions. e) Magnetic Strip: Important information regarding the debit card is stored in electronic format here and hence any kind of scratches or exposure to magnetic fields will cause damage to the card. f) EMV Chip Card: EMV stands for Europay, MasterCard and Visa. EMV is a global standard for credit and debit payment cards based on chip card technology. -

Multi-Lateral Mechanism of Cash Machines: Virtue Or Hassel

International Journal of Engineering Technology Science and Research IJETSR www.ijetsr.com ISSN 2394 – 3386 Volume 4, Issue 10 October 2017 Multi-Lateral Mechanism of Cash Machines: Virtue or Hassel Peeush Ranjan Agrawal1 and Sakshi Misra Shukla2 1 Professor, School of Management studies, MNNIT, Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh,India 2Assistant Professor, Department of MBA, S.P. Memorial Institute of Technology, Allahabad, India ABSTRACT Automated Teller Machines or Cash Machines became an organic constituent of the banking sector. The paper envisionsthe voyage that these cash machines have gone through since their initiation in the foreign banks operating in India. The study revolves around the indispensible factors in the foreign banking environment like availability, connectivity customer base, security, network gateways and clearing houses which were thoroughly reviewed and analyzed in the research paper. The methodology of the research paper includes literature review, derivation of variables, questionnaire formulation, pilot testing, data collectionand application of statistical tools with the help of SPSS software. The paper draws out findings related to the usage, congregation, multi-lateral functioning, security and growth of ATMs in the foreign banks operating in the country. The paper concludes by rendering recommendations to theforeign bankers to vanquish the stumbling blocks of the cash machines functioning. Keywords: ATMs, Cash Machines, Anywhere Banking, Foreign Banking, Online Banking 1. INTRODUCTION The Automated Teller Machine (ATM) has become an integral part of banking operations. Initially perceived as ‘cash machines’, which dispenses cash to depositors, ATMs can accept deposits, sell postage stamps, print statements and be used at institutions where the depositor does not have an account. -

Assessing Payments Systems in Latin America

Assessing payments systems in Latin America An Economist Intelligence Unit white paper sponsored by Visa International Assessing payments systems in Latin America Preface Assessing payments systems in Latin America is an Economist Intelligence Unit white paper, sponsored by Visa International. ● The Economist Intelligence Unit bears sole responsibility for the content of this report. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s editorial team gathered the data, conducted the interviews and wrote the report. The author of the report is Ken Waldie. The findings and views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsor. ● Our research drew on a wide range of published sources, both government and private sector. In addition, we conducted in-depth interviews with government officials and senior executives at a number of financial services companies in Latin America. Our thanks are due to all the interviewees for their time and insights. May 2005 © The Economist Intelligence Unit 2005 1 Assessing payments systems in Latin America Contents Executive summary 4 Brazil 17 The financial sector 17 Electronic payments systems 7 Governing institutions 17 Electronic payment products 7 Banks 17 Conventional payment cards 8 Clearinghouse systems 18 Smart cards 8 Electronic payment products 18 Stored value cards 9 Credit cards 18 Internet-based Payments 9 Debit cards 18 Payment systems infrastructure 9 Smart cards and pre-paid cards 19 Clearinghouse systems 9 Direct credits and debits 19 Card networks 10 Strengths and opportunities 19 -

Visa Inc. V. Stoumbos

No. 15-____ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States VISA INC., ET AL., Petitioners, v. MARY STOUMBOS, ET AL., Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI KENNETH A. GALLO ANTHONY J. FRANZE PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, Counsel of Record WHARTON & MARK R. MERLEY GARRISON LLP MATTHEW A. EISENSTEIN 2001 K STREET, NW ARNOLD & PORTER LLP WASHINGTON, DC 20006 601 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, (202) 223-7300 NW [email protected] WASHINGTON, DC 20001 (202) 942-5000 Counsel for Petitioners [email protected] MasterCard Incorporated and MasterCard International Counsel for Petitioners Visa Inc., Incorporated Visa U.S.A. Inc., Visa Interna- tional Service Association, and Plus System, Inc. i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether allegations that members of a business as- sociation agreed to adhere to the association’s rules and possess governance rights in the association, without more, are sufficient to plead the element of conspiracy in violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1, as the Court of Appeals held below, or are insufficient, as the Third, Fourth, and Ninth Circuits have held. ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS Pursuant to Rule 14.1(b), the following list identi- fies all of the parties appearing here and before the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. The petitioners here and appellees below in both Stoumbos v. Visa Inc., et al., No. 1:11-cv-01882 (D.D.C.) (“Stoumbos”) and National ATM Council, et al.