Submission to the Reserve Bank of Australia Response to EFTPOS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eftpos Payment Asustralia Limited Submission to Review of The

eftpos Payments Australia Limited Level 11 45 Clarence Street Sydney NSW 2000 GPO Box 126 Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone +61 2 8270 1800 Facsimile +61 2 9299 2885 eftposaustralia.com.au 22 January 2021 Secretariat Payments System Review The Treasury Langton Crescent PARKES ACT 2600 [email protected] Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the Treasury Department’s Payments System Review: Issues Paper dated November 2020 (Review). The Review is timely as Australia’s payments system is on the cusp of a fundamental transformation driven by a combination of digital technologies, nimble new fintech players and changes in consumer and merchant payment preferences accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is conducting its Retail Payments Regulatory Review, which commenced in 2019 (RBA Review) but was postponed due to COVID-19 and there is a proposal to consolidate Australia’s domestic payments systems which has potential implications for competition within the Australian domestic schemes, as well as with existing and emerging competitors in the Australian payments market through all channels. Getting the regulatory architecture right will set Australia up for success in the digital economy for the short term and in years to come. However, a substandard regulatory architecture has the potential to stall technologically driven innovation and stymie future competition, efficiencies and enhanced end user outcomes. eftpos’ response comprises: Part A – eftpos’ position statement Part B – eftpos’ background Part C – responses to specific questions in the Review. We would be pleased to meet to discuss any aspects of this submission. Please contact Robyn Sanders on Yours sincerely Robyn Sanders General Counsel and Company Secretary eftpos Payments Australia Limited ABN 37 136 180 366 Public eftpos Payments Australia Limited Level 11 45 Clarence Street Sydney NSW 2000 GPO Box 126 Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone +61 2 8270 1800 Facsimile +61 2 9299 2885 eftposaustralia.com.au A. -

Download (490Kb)

i -------- ----------------------- --------- COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES * * * Directorate-General Information, Commun1cat1on, Culture * * * * a newssheet for journalists Weekly nu 31/90 8 - 15 October 1990 SUMMARY P. 2 CONSUMERS: Eurocheques in the dock The European Commission feels users have had a raw deal, especially in France. P. 3 TOURISM: Italy proposes it be included in the Treaty of Rome But the procedure is long and complex, even though it has majority support in the Council of Ministers. P. 5 IMMIGRATION: Integrating 8 million immigrants An experts• report suggests how it could be done. P. 7 ENERGY: Substantial savings durinq the 1980s ... but oil imports still accounted for 36% of consumption. P. 8 ENERGY: Revolutionary nuclear power stations for the year 2040 The European Commission proposes a new fusion programme. P. 9 TQ~RISM~_The charms of the cqgDsrysid~ Community action plan in favour of rural tourism. Mailed from: Brussels X The contents of th1s publ1cdt1on do not necessanly reflect tt>e off1c1al v1ews of the lllStltutlons of the Commun1ty Reprodurt1on authonzed 200 rucc de ICJl_ul • 1049 Brussels • Beig1um • Tel 235 11 11 • Te!ex 21877 COMEU B Eurofocus 31/90 2. CONSUMERS: Eurocheques in the dock The European Commission feels users have had a raw deal, especially in France. In 1989 some 42mn. Eurocheques were issued abroad, including 27mn. within the European Community, for a total value of ECU 5,000mn.*. Practical, guaranteed, accepted virtually everywhere, Eurocheques have been used in increasingly large numbers since the last 15 years. In 1984 the European Commission even granted Eurocheque International, which had launched the scheme, an exemption from the EC's very strict competition rules. -

NPCI Appoints FIME to Set up the Certification Body for India's

NPCI appoints FIME to set up the certification body for India’s Payment Scheme, RuPay FIME to define, manage and execute certification programme for RuPay 6 March 2014 – National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), the umbrella organisation of all retail payment systems in the country, has appointed advanced secure-chip testing provider FIME to deliver its RuPay certification programme. NPCI will utilise FIME’s expertise in setting up EMV®-based certification board for its card payment scheme- RuPay. FIME will define the certification specification, laboratory setup, test plan specification, test tools and operate the certification board for RuPay. FIME will also be involved in setting up the certification process including the associated administrative and business operations. This certification board will be effective from March 2014. This will ensure all payment cards and point-of-sale terminals deployed under the brand align to the requirements of RuPay specifications. It will also ensure necessary infrastructural alignment of acquirers and issuers with the payment system. Prakash Sambandam, Director of FIME India says: “Many countries have, or are in the process of migrating to the EMV payment standard. Transitioning to a chip payment infrastructure will take time and require the implementation of new product development cycles. Adhering to RuPay, an EMV payment scheme will ensure that the products achieve the required functional and security standards and perform as intended, once live in the marketplace. This level of compliance is vital to ensure product interoperability and security optimisation”. In addition to enhanced security, the new payment platform presents opportunities to deliver advanced payment solutions – such as mobile and contactless payments – which are based on secure-chip technology. -

January / February 1995

The Ecologist Vol 25 Nol January/February 1995 ^ J £3.50 (US $7) New- Diseases - Old Plagues Who's Behind the Ecolabel? Mexico - Wall Street on the Warpath Oestrogen Overdose Ozone Backlash ISSN DEbl-3131 0 1 > The Unsettling of Tibet 770261"313010 Housing Plans and Policies ONA ODERN ANET RICHARD D NORTH 'Richard D North has long been one of the best informed and most thought provoking writers on the whole nexus of environmental and develop ment issues. This sharp and intelligent book shows North at the top of his form, arguing convincingly that concern about the future of our globe does not require you to be a modish ecopessimist. It comes like a sunburst of rational optimism and commonsense.' CHRISTOPHER PATTEN Governor of Hong Kong and former Secretary of State for the Environment (1989-1990) The Ecologist is published by Ecosystems Ltd. Editorial Office and Back Issues: Agriculture House, Bath Road, Sturminster Newton, Dorset, DT10 1DU, UK. Tel: (01258) 473476 Fax: (01258) 473748 E-Mail [email protected] Subscriptions: RED Computing, The Outback, 58-60 Kingston Road, New Maiden, Surrey, KT3 3LZ, United Kingdom Tel: (01403) 782644 Fax: (0181) 942 9385 Books: WEC Books, Worthyvale Manor, Camelford, Cornwall, PL32 9TT, United Kingdom Tel: (01840) 212711 Fax: (01840) 212808 Annual Subscription Rates Advertising Contributions £21 (US$34) for individuals and schools; For information, rates and booking, contact: The editors welcome contributions, which Wallace Kingston, Jake Sales (Ecologist agent), should be typed, double-spaced, on one £45 (US$85) for institutions; 6 Cynthia Street, London, N1 9JF, UK side of the paper only. -

Authorisation Service Sales Sheet Download

Authorisation Service OmniPay is First Data’s™ cost effective, Supported business profiles industry-leading payment processing platform. In addition to card present POS processing, the OmniPay platform Authorisation Service also supports these transaction The OmniPay platform Authorisation Service gives you types and products: 24/7 secure authorisation switching for both domestic and international merchants on behalf of merchant acquirers. • Card Present EMV offline PIN • Card Present EMV online PIN Card brand support • Card Not Present – MOTO The Authorisation Service supports a wide range of payment products including: • Dynamic Currency Conversion • Visa • eCommerce • Mastercard • Secure eCommerce –MasterCard SecureCode, Verified by Visa and SecurePlus • Maestro • Purchase with Cashback • Union Pay • SecureCode for telephone orders • JCB • MasterCard Gaming (Payment of winnings) • Diners Card International • Address Verification Service • Discover • Recurring and Installment • BCMC • Hotel Gratuity • Unattended Petrol • Aggregator • Maestro Advanced Registration Program (MARP) Supported authorisation message protocols • OmniPay ISO8583 • APACS 70 Authorisation Service Connectivity to the Card Schemes OmniPay Authorisation Server Resilience Visa – Each Data Centre has either two or four Visa EAS servers and resilient connectivity to Visa Europe, Visa US, Visa Canada, Visa CEMEA and Visa AP. Mastercard – Each Data Centre has a dedicated Mastercard MIP and resilient connectivity to the Mastercard MIP in the other Data Centre. The OmniPay platform has connections to Banknet for both European and non-European authorisations. Diners/Discover – Each Data Centre has connectivity to Diners Club International which is also used to process Discover Card authorisations. JCB – Each Data Centre has connectivity to Japan Credit Bureau which is used to process JCB authorisations. UnionPay – Each Data Centre has connectivity to UnionPay International which is used to process UnionPay authorisations. -

The Shadow Economy in Norway: Demand for Currency Approach

MEMORANDUM No 10/2004 The shadow economy in Norway: Demand for currency approach Isilda Shima ISSN: 0801-1117 Department of Economics University of Oslo This series is published by the In co-operation with University of Oslo The Frisch Centre for Economic Department of Economics Research P. O.Box 1095 Blindern Gaustadalleén 21 N-0317 OSLO Norway N-0371 OSLO Norway Telephone: + 47 22855127 Telephone: +47 22 95 88 20 Fax: + 47 22855035 Fax: +47 22 95 88 25 Internet: http://www.oekonomi.uio.no/ Internet: http://www.frisch.uio.no/ e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] List of the last 10 Memoranda: No 09 Steinar Holden. Wage formation under low inflation. 22 pp. No 08 Steinar Holden and Fredrik Wulfsberg Downward Nominal Wage Rigidity in Europe. 33 pp. No 07 Finn R. Førsund and Michael Hoel Properties of a non-competitive electricity market dominated by hydroelectric power. 24 pp. No 06 Svenn-Erik Mamelund An egalitarian disease? Socioeconomic status and individual survival of the Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918-19 in the Norwegian capital of Kristiania. 24 pp. No 05 Snorre Kverndokk, Knut Einar Rosendahl and Thomas F. Rutherford Climate policies and induced technological change: Impacts and timing of technology subsidies. 34 pp. No 04 Halvor Mehlum, Edward Miguel and Ragnar Torvik Rainfall, Poverty and Crime in 19th Century Germany. 25 pp. No 03 Halvor Mehlum Exact Small Sample Properties of the Instrumental Variable Estimator. A View From a Different Angle. 14 pp. No 02 Karine Nyborg and Kjetil Telle A dissolving paradox: Firms’ compliance to environmental regulation. -

New Debit Card Solutions At

New Debit Card Solutions Debit Mastercard and Visa Debit are ready Swiss Banking Services Forum, 22 May 2019 Philippe Eschenmoser, Head Cards & A2A, Swisskey Ltd Maestro/V PAY Have Established Themselves As the “Key to the Account” – Schemes, However, Are Forcing Market Entry For Successor Products Response from the Maestro and V PAY are successful… …but are not future-capable products schemes # cards Maestro V PAY on Lower earnings potential millions8 for issuers as an alternative payment traffic products (e.g. 6 credit cards, TWINT) Issuer 4 V PAY will be 2 decommissioned by VISA Functional limitations: in 20211 – Visa Debit as 0 • No e-commerce the successor 2000 2018 • No preauthorizations Security and stability have End- • No virtualization proven themselves customer High acceptance in CH and Merchants with an online MasterCard is positioning abroad in Europe offer are demanding an DMC in the medium term online-capable debit as the successor to Standard product with an Merchan product Maestro integrated bank card t 2 1: As of 2021 no new V PAY may be issued TWINT (Still) No Substitute For Debit Cards – Credit Cards With Divergent Market Perception TWINT (still) not alternative for debit Credit cards a no alternative for debit Lacking a bank card Debit function Limited target group (age, ~1.1 M 1 ~10 M. creditworthiness...) Issuer ~48.5 k ~170 k1 No direct account debiting DMC/ Visa Debit Potentially high annual fee End-customer Lower customer penetration Banks and merchants DMC/ P2P demand an online- Higher costs Merchant Visa Debit -

How Mpos Helps Food Trucks Keep up with Modern Customers

FEBRUARY 2019 How mPOS Helps Food Trucks Keep Up With Modern Customers How mPOS solutions Fiserv to acquire First Data How mPOS helps drive food truck supermarkets compete (News and Trends) vendors’ businesses (Deep Dive) 7 (Feature Story) 11 16 mPOS Tracker™ © 2019 PYMNTS.com All Rights Reserved TABLEOFCONTENTS 03 07 11 What’s Inside Feature Story News and Trends Customers demand smooth cross- Nhon Ma, co-founder and co-owner The latest mPOS industry headlines channel experiences, providers of Belgian waffle company Zinneken’s, push mPOS solutions in cash-scarce and Frank Sacchetti, CEO of Frosty Ice societies and First Data will be Cream, discuss the mPOS features that acquired power their food truck operations 16 23 181 Deep Dive Scorecard About Faced with fierce eTailer competition, The results are in. See the top Information on PYMNTS.com supermarkets are turning to customer- scorers and a provider directory and Mobeewave facing scan-and-go-apps or equipping featuring 314 players in the space, employees with handheld devices to including four additions. make purchasing more convenient and win new business ACKNOWLEDGMENT The mPOS Tracker™ was done in collaboration with Mobeewave, and PYMNTS is grateful for the company’s support and insight. PYMNTS.com retains full editorial control over the findings presented, as well as the methodology and data analysis. mPOS Tracker™ © 2019 PYMNTS.com All Rights Reserved February 2019 | 2 WHAT’S INSIDE Whether in store or online, catering to modern consumers means providing them with a unified retail experience. Consumers want to smoothly transition from online shopping to browsing a physical retail store, and 56 percent say they would be more likely to patronize a store that offered them a shared cart across channels. -

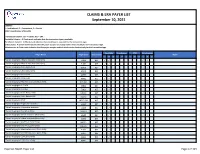

Claims and Remits Payer List

CLAIMS & ERA PAYER LIST September 10, 2021 LEGEND: I = Institutional, P = Professional, D = Dental COB = Coordination of Benefits Transaction Column: 837 = Claims, 835 = ERA Available Column: A Check-mark indicates that the transaction type is available. Enrollment Column: A Check-mark indicates that enrollment is required for the transaction type. COB Column: A Check-mark Indicates that the payer accepts secondary claims electronically for the transaction type. Attachments: A Check-mark indicates that the payer accepts medical attachments electronically for the transaction type. Available Enrollment COB Attachments Payer Name Payer Code Transaction Notes I P D I P D I P D I P D *Carisk Imaging to Allstate Insurance (Auto Only) E1069 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Allstate Insurance (Auto Only) E1069 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Geico (Auto Only) GEICO 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Geico (Auto Only) GEICO 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Nationwide A0002 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Nationwide A0002 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to New York City Law Department NYCL001 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to NJ-PLIGA E3926 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to NJ-PLIGA E3926 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to North Dakota WSI NDWSI 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to North Dakota WSI NDWSI 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to NYSIF NYSIF1510 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Progressive Insurance E1139 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Progressive Insurance E1139 835 ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Pure (Auto Only) PURE01 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ *Carisk Imaging to Safeco Insurance (Auto Only) E0602 837 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ -

The Dreams of the Cashless Society: a Study of EFTPOS in New Zealand

Journal of International Information Management Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 5 1999 The dreams of the cashless society: A study of EFTPOS in New Zealand Erica Dunwoodie Advantage Group Limited Michael D. Myers University of Auckland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/jiim Part of the Management Information Systems Commons Recommended Citation Dunwoodie, Erica and Myers, Michael D. (1999) "The dreams of the cashless society: A study of EFTPOS in New Zealand," Journal of International Information Management: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/jiim/vol8/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International Information Management by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dunwoodie and Myers: The dreams of the cashless society: A study of EFTPOS in New Zeal TheDreaima^Jhe^^ Journal of International InformcUiojiManagem^ The dreams of the cashless society: A study of EFTPOS in New Zealand Erica Dunwoodie Advantage Group Limited Michael E>. Myers University of Auckland ABSTBACT This paper looks at the way in which Utopian dreams, such as the cashless society, influ ence the adoption of information technology. Some authors claim that Utopian visions are used by IT firms to market their services and products, and that the hype that often accompanies technological innovations is part of a "large scale social process" in contemporary societies. This article discusses the social role of technological utopianism with respect to the introduc tion of EFTPOS in New Zealand. -

National Financial Inclusion Strategy

National Financial Inclu sion Strategy Summary Report Abuja, 20 January 2012 Financial Inclusion in Nigeria 14 Contents 1. Status Quo and Targets ____________________________________________________ 3 2. Scenarios, Operating Model and Regulatory Requirements ________________________ 40 3. Stakeholder Roles and Responsibilities _______________________________________ 58 4. Tracking Methodology _____________________________________________________ 83 5. Implementation Plan ______________________________________________________ 91 6 Conclusion _____________________________________________________________ 103 Financial Inclusion in Nigeria 2 1. Status Quo and Targets 1.1 Introduction to Financial Inclusion The purpose of defining a Financial Inclusion (FI) strategy for Nigeria is to ensure that a clear agenda is set for increasing both access to and use of financial services within the defined timeline, i.e. by 2020. Financial Inclusion is achieved when adults 1 have easy access to a broad range of financial products designed according to their needs and provided at affordable costs. These products include payments, savings, credit, insurance and pensions. The definition of Financial Inclusion is based on: 1. Ease of access to financial products and services Financial products must be within easy reach for all groups of people and should avoid onerous requirements, such as challenging KYC procedures 2. A broad range of financial products and services Financial Inclusion implies access to a broad range of financial services including payments, -

General Notes: Germany

General notes: Germany Source for Table 1: Eurostat. Source for all other tables: Deutsche Bundesbank, unless otherwise indicated. General Note: Change in methodology and data collection method in reference year 2007 and 2014, which may cause breaks in time series compared to previous years. In reference year 2014, figures are partly estimated by reporting agents. Table 2: Settlement media used by non-MFIs Currency in circulation outside MFIs Following the introduction of the euro on 1 January 2002, these figures are provided solely at an aggregated euro area level. Value of overnight deposits held by non-MFIs Overnight deposits held at MFIs (excluding ECB). The counterpart sector “non-MFIs” includes the component “Central government sector” and the component “Rest of the world”. Thus, this indicator is not synonymous with the same term used in the ECB concept of narrow money supply (M1). For 2002-2004, German data for this item do not include overnight deposits of the counterpart sector “Central government” held at the national central bank. Narrow money supply (M1) Following the introduction of the euro on 1 January 2002, these figures are provided solely at an aggregated euro area level. Outstanding value on e-money storages issued by MFIs Covering MFIs without derogations under Article 9(1) of Regulation ECB/2013/33 (where applicable). Encompasses only data of the German scheme “Geldkarte”. Table 4: Banknotes and coins Refer to Table 3 in the “Euro area aggregate data” section. General notes: Germany 1 Table 5: Institutions offering payment services to non-MFIs Central Bank: value of overnight deposits The break in the time series in reference period 2009 is caused by deposits held by the central government sector.