01-2 Sumar.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Praxis, International Edition, 1969, No. 3-4.Pdf

PRAXIS A PHILOSOPHICAL JOURNAL Editorial Board B r a n k o B o š n ja k , D a n k o G r l ić , M il a n K a n g r g a I v a n K u v a č ić , G a jo P e t r o v ić , R u d i S u p e k , P r e d r a g V r a n ic k i Editora-in-Chief G a jo P e t r o v ić a n d R u d i S u p e k Editorial Secretary B r a n k o D e s p o t Advisory Board K o sta s A x e l o s (Paris), A l f r e d J. A y e r (O xford), Z y g m u n d B a u m a n n (Tel-Aviv), N o r m a n B ir n b a u m (Amherst), E r n s t B l o c h (Tubingen), T h o m a s B o t t o m o r e (Brighton), U m b e r t o C e r r o n i (Ro m a), M la d e n Č a l d a r o v ić (Z agreb), R o b e r t S. C o h e n (Boston), V e l jk o C v je t ič a n in (Z agreb), B o ž id a r D e b e n ja k (Ljubljana), Mi- h a il o Đ u r ić (Beograd), M a r v in F a r b e r (Buffalo), M u h a m e d F i l i- p o v ić (Sarajevo), V l a d im ir F il ip o v ić (Z agreb), E u g e n F in k (Frei burg), I v a n F o c h t (Sarajevo), E r ic h F r o m m (Mexico City), L u c ie n G o l d m a n n (Paris), A n d r e G o r z (Paris), J u r g e n H a b er m a s (F ran k furt), E r ic h H e in t e l (W ien), A g n es H e l l e r (Budapest), B esim I brahimpašić (Sarajevo), M it k o I l ie v s k i (Skopje), L eszek K o l a - k o w s k i (Warszawa), V e l jk o K o r a ć (Beograd), K a r e l K o sik (Praha), A n d r ija K r e š ić (Beograd), H e n r i L e fe b v r e (Paris), G e o r g L u - ka cs (Budapest), S e r g e M a l l e t (Paris), H e r b e r t M a r c u s e (San Diego), M ih a il o M a r k o v ić (Beograd), V o jin M il ić (Beograd), E n zo P a c i (M ilano), H o w a r d L. -

The Praxis School's Marxist Humanism and Mihailo Marković's

The Praxis School’s Marxist Humanism and Mihailo Marković’s Theory of Communication Christian Fuchs Fuchs, Christian. 2017. The Praxis School’s Marxist Humanism and Mihailo Marković’s Theory of Communication. Critique 45 (1-2): 159-182. Full version: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03017605.2016.1268456 Abstract <159:> Mihailo Marković (1923-2010) was one of the leading members of the Yugoslav Praxis Group. Among other topics, he worked on the theory of communication and dialectical meaning, which makes his approach relevant for a contemporary critical theory of communication. This paper asks: How did Mihailo Marković conceive of communication? Marković turned towards Serbian nationalism and became the Vice-President of the Serbian Socialist Party. Given that nationalism is a particular form of ideological communication, an ideological anti-praxis that communicates the principle of nationhood, a critical theory of communication also needs to engage with aspects of ideology and nationalism. This paper therefore also asks whether there is a nationalist potential in Marković’s theory in particular or even in Marxist humanism in general. For providing answers to these questions, the article revisits Yugoslav praxis philosophy, the concepts of praxis, communication, ideology and nationalism. It shows the importance of a full humanism and the pitfalls of truncated humanism in critical theory in general and the critical theory of communication in particular. Taking into account complete humanism, the paper introduces the concept of praxis communication. Keywords: praxis, praxis philosophy, Yugoslavia, Praxis School, Praxis Group, Mihailo Marković, critical theory of communication, Marxist theory, humanism, nationalism, ideology, praxis communication 1. Introduction The Praxis Group was a community of scholars in Yugoslavia. -

Rituals and Repetitions: the Displacement of Context in Marina Abramović’S Seven Easy Pieces

RITUALS AND REPETITIONS: THE DISPLACEMENT OF CONTEXT IN MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ’S SEVEN EASY PIECES by Milena Tomic B.F.A., York University, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Fine Arts – Art History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2008 © Milena Tomic, 2008 Abstract This thesis considers Seven Easy Pieces, Marina Abramović’s 2005 cycle of re-performances at the Guggenheim Museum, as part of a broader effort to recuperate the art of the 1960s and 1970s. In re-creating canonical pieces known to her solely through fragmentary documentation, Abramović helped to bring into focus how performances by Joseph Beuys, Bruce Nauman, Gina Pane, Vito Acconci, Valie Export, and herself were being re-coded by the mediating institutions. Stressing the production of difference, my analysis revolves around two of the pieces in detail. First, the Deleuzian insight that repetition produces difference sheds light on the artist’s embellishment of her own Lips of Thomas (1975) with a series of Yugoslav partisan symbols. What follows is an examination of the enduring role of this iconography, exploring the 1970s Yugoslav context as well as the more recent phenomenon of “Balkan Art,” an exhibition trend drawing upon orientalizing discourse. While the very presence of these works in Tito’s Yugoslavia complicates the situation, I show how the transplanted vocabulary of body art may be read against the complex interweaving of official rhetoric and dissident activity. I focus on two distinct interpretations of Marxism: first, the official emphasis on discipline and the body as material producer, and second, the critique of the cult of personality as well as dissident notions about the role of practice in social transformation. -

Sretenovic Dejan Red Horizon

Dejan Sretenović RED HORIZON EDITION Red Publications Dejan Sretenović RED HORIZON AVANT-GARDE AND REVOLUTION IN YUGOSLAVIA 1919–1932 kuda.org NOVI SAD, 2020 The Social Revolution in Yugoslavia is the only thing that can bring about the catharsis of our people and of all the immorality of our political liberation. Oh, sacred struggle between the left and the right, on This Day and on the Day of Judgment, I stand on the far left, the very far left. Be‑ cause, only a terrible cry against Nonsense can accelerate the whisper of a new Sense. It was with this paragraph that August Cesarec ended his manifesto ‘Two Orientations’, published in the second issue of the “bimonthly for all cultural problems” Plamen (Zagreb, 1919; 15 issues in total), which he co‑edited with Miroslav Krleža. With a strong dose of revolutionary euphoria and ex‑ pressionistic messianic pathos, the manifesto demonstrated the ideational and political platform of the magazine, founded by the two avant‑garde writers from Zagreb, activists of the left wing of the Social Democratic Party of Croatia, after the October Revolution and the First World War. It was the struggle between the two orientations, the world social revolution led by Bolshevik Russia on the one hand, and the world of bourgeois counter‑revolution led by the Entente Forces on the other, that was for Cesarec pivot‑ al in determining the future of Europe and mankind, and therefore also of the newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Cro‑ ats and Slovenes (Kingdom of SCS), which had allied itself with the counter‑revolutionary bloc. -

Borislav Mikulić

Poietic Notion of Practice and Its Cultural Context Praxis Philosophy in the Political, Theoretical and Artistic Turmoils in the 1960s1 221 Borislav MIKULIĆ Abstract: The aim of this essay is to present the philosophy of praxis as a theoretical medium which embodies the aspects of the high and popular cul- ture in the 1960s in Croatia and former Yugoslavia. The first part deals with the topic of the lack of references to praxis in the recent contribution to the ethnography of socialism and cultural studies as a symptom of scientific reduc- tionism; in the second part some arguments are presented for the relevance of philosophy in general and praxis in particular, as a (meta-)cultural form. The third part presents and comments the conflict regarding the theory of reflection, which has marked the thinking in different theoretical fields in the 1950s, and which became the foundational event for the praxis itself. The author is trying to provide a philosophically immanent political interpretation of the paradox that the philosophical/theoretical criticism of Stalinism leads philosophy to a direct conflict with the political apparatus in power which has itself carried out the same critique during dramatic political process in 1948. In the final part, the text points out, on the one hand, to the philosophical theorem of sponta- neity in art as a fundament of the praxis concept of autonomy of the subject, and on the other, to the striking lack of references, within the mainstream of praxis, to the avant-garde political conception of art of the EXAT 51 group from early 1950s; the text outlines the reasons for interpretation of this meta- theory of art as a political anticipation of praxis. -

GAJO-PETROVIC-BOOK.Pdf

GAJO PETROVIĆ – ČOVJEK I FILOZOF ZBORNIK RADOVA S KONFERENCIJE POVODOM 80. OBLJETNICE ROĐENJA GAJO PETROVIC BOOK.indb 1 5.6.2008 10:45:19 GAJO PETROVIĆ – čOVJEK I FILOZOF ZBORNIK RADOVA S KONFERENCIJE POVODOM 80. OBLJETNICE ROđENJA Izdavač Sveučilište u zagrebu Filozofski fakultet FF Press, Zagreb Za izdavača Miljenko Jurković Urednik Lino Veljak Recenzenti Rastko Močnik Nadežda čačinovič Lektura Asja Petrović (hrvatski) Damir Kalogjera (engleski) Grafička oprema Boris Bui Tisak CIP zapis dostupan u računalnom katalogu Nacionalne i sveučilišne knjižnice u zagrebu pod brojem 669281. ISBN 978-953-175-293-0 Tiskanje ove knjige financijski je pomoglo Ministarstvo znanosti, obrazovanja i športa RH sadrzaj - gajo petrovic.indd 2 3.7.2008 10:32:01 Urednik Lino Veljak GAJO PETROVIĆ ČOVJEK I FILOZOF ZBORNIK RADOVA S KONFERENCIJE POVODOM 80. OBLJETNICE ROĐENJA Zagreb, 2008. GAJO PETROVIC BOOK.indb 3 5.6.2008 10:45:20 GAJO PETROVIC BOOK.indb 4 5.6.2008 10:45:20 SADRŽAJ Sadržaj 5 Uvod 7 I. Jűrgen Habermas: U spomen na Gaju Petrovića / Zum Gedenken an Gajo Petrović 11 Milan Kangrga: Sjećanja na prijatelja, druga i suradnika Gaju Petrovića 19 Ivan Kuvačić: Gajo Petrović kao student 23 Vlado Sruk: Nekoliko rečenica o Gaji Petroviću 27 Nebojša Popov: Gajo Petrović nije bio samo profesor 31 Goran Švob: Gajo Petrović kao logičar 43 Ante Lešaja: Gajo Petrović i Korčula 49 II. Gajo Sekulić: Gajo Petrović o toleranciji 65 Božidar Jakšić: «Praxis» Gaje Petrovića 85 Veselin Golubović: Čemu mislioci u oskudnom vremenu? 107 Slobodan Sadžakov: Gajo Petrović – Odgovornost intelektualca 111 Barbara Stamenković/Lino Veljak: Humanizam u djelu Gaje Petrovića 117 Gordana Škorić: Petrović i neki aspekti suvremene njemačke fi lozofi je 123 Mladen Labus: Mogućnost stvaralaštva u djelu Gaje Petrovića 137 Borislav Mikulić: Revolucija i intervencija. -

Praxis, Student Protest, and Purposive Social Action: the Humanist Marxist Critique of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, 1964-1975

PRAXIS, STUDENT PROTEST, AND PURPOSIVE SOCIAL ACTION: THE HUMANIST MARXIST CRITIQUE OF THE LEAGUE OF COMMUNISTS OF YUGOSLAVIA, 1964-1975 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts by Sarah D. Žabić August 2010 Thesis written by Sarah D. Žabić B.A., Indiana University, 2000 M.A., Kent State University, 2010 Approved by ___________________________________ , Advisor Richard Steigmann-Gall, Ph.D. ___________________________________ , Chair, Department of History Kenneth J. Bindas, Ph.D. ___________________________________ , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences John R.D. Stalvey, Ph.D. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................ iv INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER I The Yugoslav Articulation of Humanist Marxism: The Praxis School ..................... 24 New Plurality in Socialist Discourse: An Ideological “Thaw” in the Early 1960s ... 31 The Praxis School Platform....................................................................................... 40 The Korčula Summer School..................................................................................... 60 Conclusion ................................................................................................................. 64 CHAPTER II The “Red Choir” in Action: The Yugoslav Student Protest, June 1968................... -

The Reception of Critical Theory in the Former Yugoslavia

Praxis Philosophy’s ’Older Sister‘ The Reception of Critical Theory in the Former Yugoslavia Marjan Ivković* Without any doubt, the former Yugoslavia was among the more fertile soils globally for the reception and flourishing of the tradition of Critical Theory over a span of several decades. Practically all major works by both the ‘first’- and ‘second-generation’ critical theorists were translated into Serbo-Croatian in the 1970s and 1980s. Not only were there translations of the most influential studies of Critical Theory’s history and theoretical legacy of that time (Martin Jay, Alfred Schmidt and Gian-Enrico Rusconi), there were also studies by local authors such as Simo Elaković’s Filozofija kao kritika društva (Philosophy as Critique of Society) and Žarko Puhovski’s Um i društvenost (Reason and Sociality). Contemporary Serbian political scientist Đorđe Pavićević remarks about Critical Theory in Yugoslavia that “this group of authors can perhaps be considered the most thoroughly covered area of scholarhip within political theory and philosophy in terms of both translations and original works up to the early 1990s” (2011: 51). Yet, throughout socialist times, the broad and differentiated reception of Critical Theory never really crossed the threshold of a truly original appropriation, whether it be attempts to elaborate existing perspectives in Critical Theory, modify them in light of particular socio-historical circumstances of the local context, or apply them as a research framework for the empirical study of society. The peculiarity -

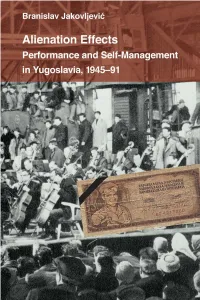

Performance and Self-Management in Yugoslavia, 1945–91

ALIENATION EFFECTS THEATER: THEORY/TEXT/PERFORMANCE Series Editors: David Krasner, Rebecca Schneider, and Harvey Young Founding Editor: Enoch Brater Recent Titles: Long Suffering: American Endurance Art as Prophetic Witness by Karen Gonzalez Rice Alienation Effects: Performance and Self-Management in Yugoslavia, 1945–91 by Branislav Jakovljević After Live: Possibility, Potentiality, and the Future of Performance by Daniel Sack Coloring Whiteness: Acts of Critique in Black Performance by Faedra Chatard Carpenter The Captive Stage: Performance and the Proslavery Imagination of the Antebellum North by Douglas A. Jones, Jr. Acts: Theater, Philosophy, and the Performing Self by Tzachi Zamir Simming: Participatory Performance and the Making of Meaning by Scott Magelssen Dark Matter: Invisibility in Drama, Theater, and Performance by Andrew Sofer Passionate Amateurs: Theatre, Communism, and Love by Nicholas Ridout Paul Robeson and the Cold War Performance Complex: Race, Madness, Activism by Tony Perucci The Sarah Siddons Audio Files: Romanticism and the Lost Voice by Judith Pascoe The Problem of the Color[blind]: Racial Transgression and the Politics of Black Performance by Brandi Wilkins Catanese Artaud and His Doubles by Kimberly Jannarone No Safe Spaces: Re-casting Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality in American Theater by Angela C. Pao Embodying Black Experience: Stillness, Critical Memory, and the Black Body by Harvey Young Illusive Utopia: Theater, Film, and Everyday Performance in North Korea by Suk-Young Kim Cutting Performances: Collage Events, Feminist Artists, and the American Avant-Garde by James M. Harding Alienation Effects PERFORMANCE AND SELF-MaNAGEMENT IN YUGOSLAVIA, 1945– 91 Branislav Jakovljević ANN ARBOR University of Michigan Press Copyright © 2016 by the University of Michigan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

Praxis, International Edition, 1973, No. 4.Pdf

PRAXIS REVUE PHILOSOPHIQUE EDITION INTERNATIONALE Comite de redaction Branko Bošnjak, Danko Grlić, Milan Kangrga, Veljko Korać, Andrija Krešić, Ivan Kuvačić, Mihailo Marković, Gajo Petrović, Svetozar Stojanović, Rudi Supek, Ljubomir Tadić, Predrag Vranicki, Miladin Životić Redacteurs en chef Veljko Korać et Gajo Petrović Secretaires de redaction Branko Despot et Nebojša Popov Redacteur technique Gvozden Flego Comite de soutien Kostas Axelos (Paris), Alfred J. Ayer (Oxford), Zygmund Baumann (Tel-Aviv), Norman Birnbaum (Amherst), Ernst Bloch (Tubingen), Thomas Bottomore (Brighton), Umberto Cerroni (Roma), Mladeri Caldarović (Zagreb), Robert S. Cohen (Boston), Veljko Cvjetičanin (Zagreb), Božidar Debenjak (Ljubljana), Mihailo Đurić (Beograd), Marvin Farber (Buffalo), Vladimir Filipović (Zagreb), Eugen Fink (Freiburg), Ivan Focht (Sarajevo), Erich Fromm (Mexico City), f Lucien Goldmann (Paris), Zagorka Golubović (Beograd), Andre Gorz (Paris), Jurgen Habermas (Starnberg), Erich Heintel (Wien), Agnes Heller (Budapest), Besim Ibrahimpašić (Sarajevo), Mitko llievski (Skopje), Leszek Kolakowski (Warszawa), Karel Kosik (Praha), Henri Lefebvre (Paris), f Georg Lukacs (Budapest), / Serge Mallet (Paris), Herbert Marcuse (San Diego), Enzo Pad (Milano), Howard L. Parsons (Bridgeport), David Riesman (Cam bridge, Mass.), Veljko Rus (Ljubljana), Abdulah Sarčević (Sara jevo), Ivan Varga (Budapest), Kurt H. Wolff (Newton, Mass.), Aldo Zanardo (Bologna). Editeurs HRVATSKO FILOZOFSKO DRUŠTVO SAVEZ FILOZOFSKIH DRUŠTAVA JUGOSLAVIJE L’edition internationale -

Zpth – Zeitschrift Für Politische Theorie 2-2017

www.ssoar.info Praxis Philosophy's 'Older Sister': the Reception of Critical Theory in the Former Yugoslavia Ivković, Marjan Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: Verlag Barbara Budrich Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Ivković, M. (2017). Praxis Philosophy's 'Older Sister': the Reception of Critical Theory in the Former Yugoslavia. ZPTh - Zeitschrift für Politische Theorie, 8(2), 271-280. https://doi.org/10.3224/zpth.v8i2.10 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-SA Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-SA Licence Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen) zur Verfügung gestellt. (Attribution-ShareAlike). For more Information see: Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-60685-8 Praxis Philosophy’s ’Older Sister‘ The Reception of Critical Theory in the Former Yugoslavia Marjan Ivković* Without any doubt, the former Yugoslavia was among the more fertile soils globally for the reception and flourishing of the tradition of Critical Theory over a span of several decades. Practically all major works by both the ‘first’- and ‘second-generation’ critical theorists were translated into Serbo-Croatian in the 1970s and 1980s. Not only were there translations of the most influential studies of Critical Theory’s history and theoretical legacy of that time (Martin Jay, Alfred Schmidt and Gian-Enrico Rusconi), there were also studies by local authors such as Simo Elaković’s Filozofija kao kritika društva (Philosophy as Critique of Society) and Žarko Puhovski’s Um i društvenost (Reason and Sociality). -

Praxis Društvena Kritika I Humanistički Socijalizam

Uredili Dragomir Olujić Oluja i Krunoslav Stojaković PRAXIS DRUŠTVENA KRITIKA I HUMANISTIČKI SOCIJALIZAM ZBORNIK RADOVA SA MEĐUNARODNE KONFERENCIJE O JUGOSLAVENSKOJ LJEVICI: PRAXIS-FILOZOFIJA I KORČULANSKA LJETNA ŠKOLA (1963-1974)63-1974 Uredili Dragomir Olujić Oluja i Krunoslav Stojaković PRAXIS DRUŠTVENA KRITIKA I HUMANISTIČKI SOCIJALIZAM ZBORNIK RADOVA SA MEĐUNARODNE KONFERENCIJE O JUGOSLAVENSKOJ LJEVICI: PRAXIS-FILOZOFIJA I KORČULANSKA LJETNA ŠKOLA (1963-1974) Beograd, 2012 IMPRESSUM PUBLIKACIJA: PRAXIS. DRUŠTVENA KRITIKA I HUMANISTIČKI SOCIJALIZAM Zbornik radova sa Međunarodne konferencije o jugoslavenskoj ljevici: Praxis-fi lozofi ja i Korčulanska ljetna škola (1963-1974) IZDAVAČ: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Regionalna kancelarija za jugoistočnu Evropu Gospodar Jevremova 47, Beograd, Srbija UREDNIŠTVO Dragomir Olujić Oluja Krunoslav Stojaković UREDNIČKI SAVET Boris Kanzleiter AUTORI I AUTORKE TEKSTOVA: Katarzyna Bielińska-Kowalewska, Luka Bogdanić, Branka Ćurčić, Thomas Flierl, Gabriella Fusi, Zagorka Golubović, Božidar Jakšić, Hrvoje Jurić, Boris Kanzleiter, Gal Kirn, Matthias István Köhler, Michael Koltan, Ivan Kuvačić, Nada Ler Sofronić, Ante Lešaja, Dušan Marković, Predrag Matvejević, Dragomir Olujić Oluja, Nebojša Popov, Thomas Seibert, Nenad Stefanov, Krunoslav Stojaković, Alen Sućeska, Lino Veljak PREVODI: Luka Bogdanić, Tomislav Brlek, Sonja Djerasimović, Ines Meštrović FOTOGRAFIJE: Zdravko Kučinar, Rajko Grlić LEKTURA I KOREKTURA: Dragomir Olujić Oluja DIZAJN: Ana Humljan PRIPREMA ZA ŠTAMPU: Dejan Dimitrijević ŠTAMPA: Pekograf,