Provide an Analysis of the Environmental Economy in the North West and the Links Between Environment and Economic Development;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSA341 Agecroft Bro 14/1/10 11:43 Am Page 2 LAND DEVELOPMENT SERVICED of PLOTS FOUR for SALE from 1.43 - 11.40 Acres for SALE PARK COMMERCE AGECROFT

SSA341 Agecroft Bro 14/1/10 11:43 am Page 2 AGECROFT AGECROFT ROAD | SALFORD COMMERCE PHASE PARK T L A A LLY S N H G E M L A E A R Y N E WA R R O W A Y A D Y 3 FORFOR SALESALE FOUR PLOTS OF SERVICED DEVELOPMENT LAND From 1.43 - 11.40 Acres (0.58 - 4.61 Hectares) SSA341 Agecroft Bro 14/1/10 11:43 am Page 3 AGECROFT AGECROFT COMMERCE COMMERCE PARK Agecroft Commerce Park is situated on the PARK site of the former Agecroft Colliery and is one of North West England’s success stories. The site which has been reclaimed by the North West Regional Development Agency A580 (NWDA) in association with English A666 Partnerships (National Coalfields Programme) is now the home to a large number of companies including Bunzl, Securicor, Nimans, Worthington Nicholls, The Juice Corporation and most recently PZ Cussons. AGECROFT RD Developers including Langtree, Priority Sites, Network Space and Scarborough have Plot 4 Plot 5 carried out successful schemes on previous Plot 2 Plot 3 phases of Agecroft Commerce Park. Plot 1 SOLD TO LAMPLIGHT PZ CUSSONS WAY BUNZL TALLYMAN WAY Description NIMANS NETWORK SECURICOR Phase 3 of Agecroft Commerce Park SPACE SQUIRREL comprises the last parcels of land of this STORAGE exciting Regeneration Project. The site infrastructure and services have all been installed. The site has been masterplanned to give a great deal of flexibility with individual plots ranging from 0.76 hectares (1.88 acres) to 4.44 hectares (10.98 acres). -

Agecroft Power Stations Generated Together the Original Boiler Plant Had Reached 30 Years for 10 Years

AGECROl?T POWER STATIONS 1924-1993 - About the author PETER HOOTON joined the electricity supply industry in 1950 at Agecroft A as a trainee. He stayed there until his retirement as maintenance service manager in 1991. Peter approached the brochure project in the same way that he approached work - with dedication and enthusiasm. The publication reflects his efforts. Acknowledgements MA1'/Y. members and ex members of staff have contributed to this history by providing technical information and their memories of past events In the long life of the station. Many of the tales provided much laughter but could not possibly be printed. To everyone who has provided informati.on and stories, my thanks. Thanks also to:. Tony Frankland, Salford Local History Library; Andrew Cross, Archivist; Alan Davies, Salford Mining Museum; Tony Glynn, journalist with Swinton & Pendlebury Journal; Bob Brooks, former station manager at Bold Power Station; Joan Jolly, secretary, Agecroft Power Station; Dick Coleman from WordPOWER; and - by no means least! - my wife Margaret for secretarial help and personal encouragement. Finally can I thank Mike Stanton for giving me lhe opportunity to spend many interesting hours talkin11 to coUcagues about a place that gave us years of employment. Peter Hooton 1 September 1993 References Brochure of the Official Opening of Agecroft Power Station, 25 September 1925; Salford Local History Library. Brochure for Agecroft B and C Stations, published by Central Electricity Generating Board; Salford Local Published by NationaJ Power, History Library. I September, 1993. Photographic albums of the construction of B and (' Edited and designed by WordPOWER, Stations; Salford Local Histo1y Libraty. -

Agecroft in Steam

( ?I ~- - - ~"~ _., -- ........... / -- . , ·--....., __ t) \ ,-- The 1960's saw a dramatic change m the use of The 'A' station system was abandoned early m steam locomotion in the North West of 1947 as construction of 'B' station cooling to Cl!Jton Junc1:c'n ) England. Within the short space of 8 years the towers severed the line. Between then and its QI✓ . familiar sight of a steam-hauled train closure the 'A' station received coal by road. {not all 1he rm,ways shown exi~ad al the some time vanished completely from British Rail. For a A Stallon .,:· :·, ,: ' _::' .·. ·-~ ·.. while steam continued to be used at some ·'..,·.'. _. 1, · ,_ c · ·n... c····. ~:·y···,--·· Reception Sidings industrial sites in Lancashire but now only II AG hopper Agecroft Power Station, near Manchester, .if •i•>,c': fp , ' . ,. Ill ·• continues the tradition. Three power stations (A, B and C ) have been A completely ne w coal handling system using developed on the Agecroft site smce 1925 and steam locomotives, was built on a separate each has used a rrnl system in its coal site· to se rve···•· both 'B ' and 'C' stations. A senes of handling. lines, approximately I mile lung, was coalslockmg construc ted running from the original gmundwilh ,:···. ~ ~ -c·,.' .-:B.ft. .,. ....:;: y ·:·:· conveyor to Agecroft Junc tion. The line passed crone lrack (standard gmrgel -.. ~~:: .. ·~&--... 2 loco sheds and fanned into wagon sidings ,,,. .-n:v ...' ... which converged lo pass through the tippler. .. .. A new conveyor was built to take the coal over . .. ... the British Rail line and the canal to the power The original 'A' statio,n used a 2' 6" gauge station. -

Chapter 2 the Historical Background

CHAPTER 2 THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1 5 I GEOGRAPHICAL AND CLIMATIC FOUNDATIONS As an area of historical study the Greater milder climate, by comparison both with the Manchester County has the disadvantage of being moors and with other westerly facing parts of without an history of its own. Created by Act Britain. Opening as they do on to what is, of Parliament a little over ten years ago, it climatically speaking, an inland sea, they joins together many areas with distinct avoid much of the torrential downpours brought histories arising from the underlying by Atlantic winds to the South West of England. geographical variations within its boundaries. At the same time the hills give protection from the snow bearing easterlies. The lowland areas The Greater Manchester County is the are fertile, and consist largely of glacial administrative counterpart of 20th century deposits. urban development which has masked the diversity of old pre-industrial southeast In the northwest of the Greater Manchester Lancashire and northeast Cheshire. County the plain rises around Wigan and Standish. For centuries the broad terraced The area has three dominant geographic valley of the Rivers Mersey and Irwell, which characteristics: the moorlands; the plains; and drains the plain, has been an important barrier the rivers, most notably the Mersey/Irwell to travel because of its mosses. Now the system. region's richest farmland, these areas of moss were largely waste until the early 19th century, when they were drained and reclaimed. The central area of Greater Manchester County, which includes the major part of the The barrier of the Mersey meant that for conurbation, is an eastward extension of the centuries northeast Cheshire developed .quite Lancashire Plain, known as the 'Manchester separately from southeast Lancashire, and it Embayment1 because it lies, like a bay, between was not until the twenties and thirties that high land to the north and east. -

Walk 3 in Between

The Salford Trail is a new, long distance walk of about 50 public transport miles/80 kilometres and entirely within the boundaries The new way to find direct bus services to where you of the City of Salford. The route is varied, going through want to go is the Route Explorer. rural areas and green spaces, with a little road walking walk 3 in between. Starting from the cityscape of Salford Quays, tfgm.com/route-explorer the Trail passes beside rivers and canals, through country Access it wherever you are. parks, fields, woods and moss lands. It uses footpaths, tracks and disused railway lines known as ‘loop lines’. Start of walk The Trail circles around to pass through Kersal, Agecroft, Bus Number 92, 93, 95 Walkden, Boothstown and Worsley before heading off to Bus stop location Littleton Road Post Office Chat Moss. The Trail returns to Salford Quays from the historic Barton swing bridge and aqueduct. During the walk Bus Number 484 Blackleach Country Park Bus stop location Agecroft Road 5 3 Clifton Country Park End of walk 4 Walkden Roe Green Bus Number 8, 22 5 miles/8 km, about 2.5 hours Kersal Bus stop location Manchester Road, St Annes’s church 2 Vale 6 Worsley 7 Eccles Chat 1 more information Moss 8 Barton For information on any changes in the route please Swing Salford 9 Bridge Quays go to visitsalford.info/thesalfordtrail kersal to clifton Little Woolden 10 For background on the local history that you will This walk follows the River Irwell upstream Moss as it meanders through woodland and Irlam come across on the trail or for information on wildlife please go to thesalfordtrail.btck.co.uk open spaces to a large country park. -

The Victorian Society in Manchester Registered Charity No

The Victorian Society in Manchester Registered Charity No. 1081435 Registered Charity No.1081435 Summer Newsletter 2014 EDITORIAL has, indeed, been the subject for in other comments on the question of monographic books by Ian he clearly distinguished between the Toplis (1987) and Bernard Porter ‘Greek’ idiom of the ancient world THE BATTLE OF THE STYLES (2011) – as well as of a number of and the ‘Italian’ of the Renaissance. CONTINUED? scholarly articles, beginning with What he surely meant was a building David Brownlee’s ‘That regular in the Victorian Italianate style which, Anyone with more than a passing mongrel affair’ in 1985. Brownlee by the end of the 1850s, had become interest in Victorian architecture will conceptualized the contretemps as the expressive idiom for a far greater know about the ‘battle of the styles’ the moment when the High Victorian proportion of British architecture than that began at the start of the Queen’s movement in architecture was derailed was encompassed by neo-Gothic reign and reached its climax with by an elderly survivor (Palmerston was churches, educational buildings and the commission for new government 76 in 1860) of the earlier nineteenth- the like. It was an idiom that had just offices on Whitehall between 1856 and century Reform movement, whose as much right as the Gothic Revival 1860. The three-section competition, architectural ideas were retrogressively to claim to represent ‘the modern launched during Lord Palmerston’s late Georgian. Although more school of English architecture’, as first administration, resulted in victories nuanced interpretations have emerged W.H. Leeds called it in the title of for little-known architects peddling subsequently, that idea has basically his 1839 monograph on Charles versions of contemporary Parisian stuck. -

The Tudor Water Mill. By Peter James Corbally in 1543 Sir Robert

The Tudor Water Mill. by Peter James Corbally In 1543 Sir Robert Langley of Agecroft Hall, Lord of the Manor of Prestwich, built a weir across the River Irwell to provide water for a water mill. The weir was to raise the level of the river and pen back water that could be used to work the wheel at the mill. The weir was 20 yards long and 28 inches high above the river level raising the river level by an extra 24 inches. Presumably there was a mill race which led a forceful stream of water to the wheel. The mill and weir cost 300 marks to build and provided a profit of 40 marks per annum. It operated smoothly for four or so years. th Then on 20 June 1548, Thomas Holland, Lord of the Manor of Clifton came with six other men and broke down the end of the weir on the western bank. The water flowed out through the broken weir and the mill ceased operation. Truth to tell the western end of the weir rested on Thomas Holland’s land on the Clifton bank. Sir Robert Langley needed the co-operation of Thomas Holland in order to build the weir. The river must have been surveyed and the best spot for the weir must have rested on the Prestwich bank on the east and the Clifton bank on the west of the river. The two men, Sir Robert Langley and Thomas Holland, made a gentleman’s agreement about the weir five years earlier and Sir Robert, trusting Thomas Holland’s word, had gone ahead and built the project. -

The Tram Roads of the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal

ISSN 1476-1580 North West Geography Volume 5, Number 1, 2005 North West Geography, Volume 5, 2005 16 The Tram Roads of the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal Paul Hindle Manchester Geographical Society [email protected] Abstract: The 15 ¼ mile Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal was effectively extended by 6 ½ miles as a transport system by numerous tram roads. Evidence for them is primarily from historic maps, plus limited documentary and archaeological evidence. Key words: Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal. Tram Roads. The Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal was authorised by The evidence for these lines is difficult to obtain, as Act of Parliament in 1791, and opened from Oldfield Road such minor features of the industrial landscape were poorly in Salford to Bolton and Bury by 1797; it was connected to recorded when in use, and have long since been disused. the River Irwell in Salford in 1809. It had a total length of There appear to be no contemporary photographs of any 15¼ miles, but it was effectively extended as a transport of the lines. Substantial earthworks and structures remain system by a further 6½ miles by the creation of numerous for two of the lines; but most have left little or no trace. tram roads. However better evidence comes from various maps, The canal was essentially a coal-carrying canal; many including the first edition of the Ordnance Survey 6” (c. coal pits were sunk alongside the canal, whilst other pits 1845), the canal’s own detailed maps (1881-2), and the first were linked to it by road. -

Walk 1 in Between

The Salford Trail is a new, long distance walk of about 50 public transport miles/80 kilometres and entirely within the boundaries The new way to find direct bus services to where you of the City of Salford. The route is varied, going through want to go is Route Explorer. rural areas and green spaces, with a little road walking walk 1 in between. Starting from the cityscape of Salford Quays, tfgm.com/route-explorer the Trail passes beside rivers and canals, through country Access it wherever you are. parks, fields, woods and moss lands. It uses footpaths, tracks and disused railway lines known as ‘loop lines’. Start of walk The Trail circles around to pass through Kersal, Agecroft, Bus Number 53, 79 24, 71, 73 Walkden, Boothstown and Worsley before heading off to Bus stop location The Quays Trafford Road Chat Moss. The Trail returns to Salford Quays from the historic Barton swing bridge and aqueduct. Tram/metro Salford Quays Blackleach During the walk Country Park Bus Number 10, 27, 67, 71, 73, 92, 93, 97, 98, 5 3 Clifton Country Park 100, 101 4 Walkden Roe Green Bus stop location Blackfriars Street Kersal Victoria, Exchange Square 5 miles/8 km, about 2.5 hours 2 Vale Tram/metro 6 Worsley 7 End of walk Eccles Chat 1 Moss 8 Bus Number 8, 26, 34-37 Barton salford quays to peel park Swing Salford 9 Bridge Quays Bus stop location Salford Crescent This first leg of the Salford Trail is mainly Little an urban walk taking you from the most Woolden 10 Tram/metro Salford Quays Moss modern development around Salford Quays Train Salford Crescent Irlam alongside the Manchester Ship Canal and the River Irwell. -

03Aii Appendix One Pothole Action Fund 21 22 List of Identified

POTHOLE ACTION FUND 2021/22 FINAL PROPOSALS Street Name Neighbourhood Area Ward Primary Schemes Worsley & Boothstown Worsley & Westwood Park A580 (East Lancashire Rd) Swinton Swinton Park Claremont & Weaste Claremont A6 (Broad Street) Claremont & Weaste Claremont Douglas Green East Salford Pendleton & Charlestown Castlewood Road East Salford Kersal & Broughton Park Bury New Road East Salford Kersal & Broughton Park Park Road Eccles Eccles Weymouth Road Eccles Barton & Winton Wentworth Avenue Claremont & Weaste Weaste & Seedley Moss Meadow Road Claremont & Weaste Claremont Lord Street Irlam & Cadishead Cadishead & Lower Irlam Ridyard Street Little Hulton & Walkden Little Hulton Ashtonfield Drive Little Hulton & Walkden Walkden North Lower Seedley Road Ordsall &Langworthy Weaste & Seedley Agecroft Road Swinton & Pendlebury Pendlebury & Clifton Station Road Swinton & Pendlebury Pendlebury & Clifton Brentwood Road Worsley & Boothstown Worsley & Westwood Park Worsley Road Worsley & Boothstown Worsley & Westwood Park Astley Road Irlam & Cadishead Cadishead & Lower Irlam Reserve Schemes Manchester Road West Little Hulton & Walkden Little Hulton Algernon Road Little Hulton & Walkden Walkden North Walkden Road Little Hulton & Walkden Walkden South Roe Green Worsley & Boothstown Boothstown & Ellenbrook Eccles Old Road Ordsall &Langworthy Pendleton & Charlestown Vine Street East Salford Kersal & Broughton Park Wallness Lane East Salford Pendleton & Charlestown Littleton Road East Salford Kersal & Broughton Park Liverpool Road Eccles Barton & Winton/Eccles -

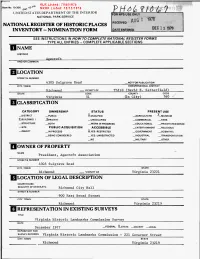

NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED DEC 1 a T978 ' SEE INSTRUCTIONS in HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS QNAME

VLR Listed: 7/18/1978 FormNo. 10-300 ^ \0-T*^ NRHP Listed: 12/13/1978 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED DEC 1 a t978 ' SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS QNAME HISTORIC Aeecroft AND/OR COMMON QLOCATION STREET* NUMBER 4305 Sulgrave Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Richmond — .VICINITYOF Third (David E. Satterfield) STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Virginia 51 (In City) 760 ^ HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED AGRICULTURE ?_MUSEUM 2LBUILDING( 1 JipRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: QOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME „ . , . ^ . President, Agecroft Association STREET & NUMBER 4305 Sulgrave Road CITY, TOWN STATE Richmond VICINITYOF Virginia 23221 HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Richmond City Hall STREET* NUMBER 900 East Broad Street CITY. TOWN STATE Richmond Virginia 23219 B REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Survey DATE December 1977 -FEDERAL X.STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEYRECORDS Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission - 221 Governor Street CITY, TOWN STATE Richmond Virginia 23219 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X EXCELLENT .DETERIORATED ^.UNALTERED X.ORIGINAL SITE GOOD -RUINS ALTERED —MOVED DATE- FAIR -UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Agecroft is situated on twenty-three acres of land located between the James River and Sulgrave Road in the Windsor Farms area of Richmond. -

74 75 Easy Access on All Buses

From 30 January Buses 74 and 75 All journeys are now run by Go Goodwins. No change to times 74 75 Easy access on all buses Irlams o’ th’ Height Agecroft Langley Road Pendleton From 30 January 2017 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays This timetable is available online at Operated by www.tfgm.com Go Goodwins PO Box 429, Manchester, M60 1HX ©Transport for Greater Manchester 16-1626–G74–3000–1216 Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request Go Goodwins large print, Braille or recorded information Lyntown Trading Estate phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com 186 Old Wellington Road, Eccles, Manchester Easy access on buses M30 9QG Telephone 0161 789 4545 Journeys run with low floor buses have no steps at the entrance, making getting on and off easier. Where shown, low floor Travelshops buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Eccles Church Street space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the Mon to Fri 7.30am to 4pm bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Sat 8am to 11.45am and 12.30pm to 3.30pm easy access services where these services are Sunday* Closed scheduled to run. Manchester Piccadilly Gardens Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm Using this timetable Sunday* 10am to 6pm Timetables show the direction of travel, bus Public hols 10am to 5.30pm numbers and the days of the week. Manchester Shudehill Interchange Main stops on the route are listed on the left.