An Example of Phenotypic Adherence to the Island Rule? – Anticosti Gray Jays Are Heavier but Not Structurally Larger Than Mainland Conspecifics Dan Strickland1 & D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ecology and Management of Moose in North America

THE ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF MOOSE IN NORTH AMERICA Douglas H. PIMLOTT Department of Lands and Forests, Maple, Ontario, Canada Concepts of the status, productivity and management of North American moose (Alces alces) have changed greatly during the past decade. The rapidity of the change is illustrated by the published record. TUFTS (1951) questioned, « Is the moose headed for extinc tion ? » and discussed the then current belief that moose populations had seriously declined across much of the continent. Five years later, PETERSON (1955: 217) stated, « It appears almost inevitable that the days of unlimited hunting for moose must soon pass from most of North America. » He also suggested (1955 : 216) that a kill of 12 to 25 per cent of the adult population is the highest that would permit the maintenance of the breeding population. Four years later, I showed (PIMLOTT, 1959a) that moose in Newfoundland could sustain a kill of twice the magnitude suggested by Peterson. I also suggested (PIMLOTT, 1959b) that the North American moose kill could be very greatly increased-in spite of progressive liberalization of hunting regulations over much of Canada and a marked increase in annual kill. It is not realistic to assume that the status of the species has changed, within the decade, from threatened extinction to annual harvests of approximately 40,000 and potential harvests of two to three times that number. Although moose populations have increased in some areas since 1950, there is little doubt that the changed think ing about moose management is more the result of the increase in knowledge than of any other factor. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

A Fossil Scrub-Jay Supports a Recent Systematic Decision

THE CONDOR A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY Volume 98 Number 4 November 1996 .L The Condor 98~575-680 * +A. 0 The Cooper Omithological Society 1996 g ’ b.1 ;,. ’ ’ “I\), / *rs‘ A FOSSIL SCRUB-JAY SUPPORTS A”kECENT ’ js.< SYSTEMATIC DECISION’ . :. ” , ., f .. STEVEN D. EMSLIE : +, “, ., ! ’ Department of Sciences,Western State College,Gunnison, CO 81231, ._ e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Nine fossil premaxillae and mandibles of the Florida Scrub-Jay(Aphelocoma coerulescens)are reported from a late Pliocene sinkhole deposit at Inglis 1A, Citrus County, Florida. Vertebrate biochronologyplaces the site within the latestPliocene (2.0 to 1.6 million yearsago, Ma) and more specificallyat 2.0 l-l .87 Ma. The fossilsare similar in morphology to living Florida Scrub-Jaysin showing a relatively shorter and broader bill compared to western species,a presumed derived characterfor the Florida species.The recent elevation of the Florida Scrub-Jayto speciesrank is supported by these fossils by documenting the antiquity of the speciesand its distinct bill morphology in Florida. Key words: Florida; Scrub-Jay;fossil; late Pliocene. INTRODUCTION represent the earliest fossil occurrenceof the ge- nus Aphelocomaand provide additional support Recently, the Florida Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma for the recognition ofA. coerulescensas a distinct, coerulescens) has been elevated to speciesrank endemic specieswith a long fossil history in Flor- with the Island Scrub-Jay(A. insularis) from Santa ida. This record also supports the hypothesis of Cruz Island, California, and the Western Scrub- Pitelka (195 1) that living speciesof Aphefocoma Jay (A. californica) in the western U. S. and Mex- arose in the Pliocene. ico (AOU 1995). -

Corvids of Cañada

!!! ! CORVIDS OF CAÑADA COMMON RAVEN (Corvus corax) AMERICAN CROW (Corvus brachyrhyncos) YELLOW-BILLED MAGPIE (Pica nuttalli) STELLER’S JAY (Cyanocitta stelleri) WESTERN SCRUB-JAY Aphelocoma californica) Five of the ten California birds in the Family Corvidae are represented here at the Cañada de los Osos Ecological Reserve. Page 1 The Common Raven is the largest and can be found in the cold of the Arctic and the extreme heat of Death Valley. It has shown itself to be one of the most intelligent of all birds. It is a supreme predator and scavenger, quite sociable at certain times of the year and a devoted partner and parent with its mate. The American Crow is black, like the Raven, but noticeably smaller. Particularly in the fall, it may occur in huge foraging or roosting flocks. Crows can be a problem for farmers at times of the year and a best friend at other times, when crops are under attack from insects or when those insects are hiding in dried up leftovers such as mummified almonds. Crows know where those destructive navel orange worms are. Smaller birds do their best to harass crows because they recognize the threat they are to their eggs and young. Crows, ravens and magpies are important members of the highway clean-up crew when it comes to roadkills. The very attractive Yellow-billed Magpie tends to nest in loose colonies and forms larger flocks in late summer or fall. In the central valley of California, they can be a problem in almond and fruit orchards, but they also are adept at catching harmful insect pests. -

S Largest Islands: Scenarios for the Role of Corvid Seed Dispersal

Received: 21 June 2017 | Accepted: 31 October 2017 DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.13041 RESEARCH ARTICLE Oak habitat recovery on California’s largest islands: Scenarios for the role of corvid seed dispersal Mario B. Pesendorfer1,2† | Christopher M. Baker3,4,5† | Martin Stringer6 | Eve McDonald-Madden6 | Michael Bode7 | A. Kathryn McEachern8 | Scott A. Morrison9 | T. Scott Sillett2 1Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA; 2Migratory Bird Center, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC, USA; 3School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia; 4School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 5CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, Ecosciences Precinct, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 6School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 7ARC Centre for Excellence for Coral Reefs Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld, Australia; 8U.S. Geological Survey- Western Ecological Research Center, Channel Islands Field Station, Ventura, CA, USA and 9The Nature Conservancy, San Francisco, CA, USA Correspondence Mario B. Pesendorfer Abstract Email: [email protected] 1. Seed dispersal by birds is central to the passive restoration of many tree communi- Funding information ties. Reintroduction of extinct seed dispersers can therefore restore degraded for- The Nature Conservancy; Smithsonian ests and woodlands. To test this, we constructed a spatially explicit simulation Institution; U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), Grant/Award Number: DEB-1256394; model, parameterized with field data, to consider the effect of different seed dis- Australian Reseach Council; Science and persal scenarios on the extent of oak populations. We applied the model to two Industry Endowment Fund of Australia islands in California’s Channel Islands National Park (USA), one of which has lost a Handling Editor: David Mateos Moreno key seed disperser. -

A Bird in Our Hand: Weighing Uncertainty About the Past Against Uncertainty About the Future in Channel Islands National Park

A Bird in Our Hand: Weighing Uncertainty about the Past against Uncertainty about the Future in Channel Islands National Park Scott A. Morrison Introduction Climate change threatens many species and ecosystems. It also challenges managers of protected areas to adapt traditional approaches for setting conservation goals, and the phil- osophical and policy framework they use to guide management decisions (Cole and Yung 2010). A growing literature discusses methods for structuring management decisions in the face of climate-related uncertainty and risk (e.g., Polasky et al. 2011). It is often unclear, how- ever, when managers should undertake such explicit decision-making processes. Given that not making a decision is actually a decision with potentially important implications, what should trigger management decision-making when threats are foreseeable but not yet mani- fest? Conservation planning for the island scrub-jay (Aphelocoma insularis) may warrant a near-term decision about non-traditional management interventions, and so presents a rare, specific case study in how managers assess uncertainty, risk, and urgency in the context of climate change. The jay is restricted to Santa Cruz Island, one of the five islands within Chan- nel Islands National Park (CINP) off the coast of southern California, USA. The species also once occurred on neighboring islands, though it is not known when or why those populations went extinct. The population currently appears to be stable, but concerns about long-term viability of jays on Santa Cruz Island have raised the question of whether a population of jays should be re-established on one of those neighboring islands, Santa Rosa. -

Efficacy of Three Vaccines in Protecting Western Scrub-Jays (Aphelocoma Californica) from Experimental Infection with West Nile

VECTOR-BORNE AND ZOONOTIC DISEASES Volume 00, Number 00, 2011 ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0173 Efficacy of Three Vaccines in Protecting Western Scrub-Jays (Aphelocoma californica) from Experimental Infection with West Nile Virus: Implications for Vaccination of Island Scrub-Jays (Aphelocoma insularis) Sarah S. Wheeler,1 Stanley Langevin,1 Leslie Woods,2 Brian D. Carroll,1 Winston Vickers,3 Scott A. Morrison,4 Gwong-Jen J. Chang,5 William K. Reisen,1 and Walter M. Boyce3 Abstract The devastating effect of West Nile virus (WNV) on the avifauna of North America has led zoo managers and conservationists to attempt to protect vulnerable species through vaccination. The Island Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma insularis) is one such species, being a corvid with a highly restricted insular range. Herein, we used congeneric Western Scrub-Jays (Aphelocoma californica) to test the efficacy of three WNV vaccines in protecting jays from an experimental challenge with WNV: (1) the Fort Dodge West Nile-InnovatorÒ DNA equine vaccine, (2) an experimental DNA plasmid vaccine, pCBWN, and (3) the Merial RecombitekÒ equine vaccine. Vaccine efficacy after challenge was compared with naı¨ve and nonvaccinated positive controls and a group of naturally immune jays. Overall, vaccination lowered peak viremia compared with nonvaccinated positive controls, but some WNV-related pathology persisted and the viremia was sufficient to possibly infect susceptible vector mosquitoes. The Fort Dodge West Nile-Innovator DNA equine vaccine and the pCBWN vaccine provided humoral immune priming and limited side effects. Five of the six birds vaccinated with the Merial Recombitek vaccine, including a vaccinated, non-WNV challenged control, developed extensive necrotic lesions in the pectoral muscle at the vaccine inoculation sites, which were attributed to the Merial vaccine. -

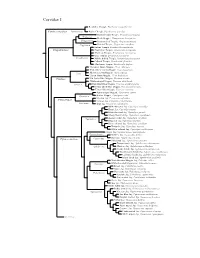

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Distribution Habitat and Social Organization of the Florida Scrub Jay

DISTRIBUTION, HABITAT, AND SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE FLORIDA SCRUB JAY, WITH A DISCUSSION OF THE EVOLUTION OF COOPERATIVE BREEDING IN NEW WORLD JAYS BY JEFFREY A. COX A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1984 To my wife, Cristy Ann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank, the following people who provided information on the distribution of Florida Scrub Jays or other forms of assistance: K, Alvarez, M. Allen, P. C. Anderson, T. H. Below, C. W. Biggs, B. B. Black, M. C. Bowman, R. J. Brady, D. R. Breininger, G. Bretz, D. Brigham, P. Brodkorb, J. Brooks, M. Brothers, R. Brown, M. R. Browning, S. Burr, B. S. Burton, P. Carrington, K. Cars tens, S. L. Cawley, Mrs. T. S. Christensen, E. S. Clark, J. L. Clutts, A. Conner, W. Courser, J. Cox, R. Crawford, H. Gruickshank, E, Cutlip, J. Cutlip, R. Delotelle, M. DeRonde, C. Dickard, W. and H. Dowling, T. Engstrom, S. B. Fickett, J. W. Fitzpatrick, K. Forrest, D. Freeman, D. D. Fulghura, K. L. Garrett, G. Geanangel, W. George, T. Gilbert, D. Goodwin, J. Greene, S. A. Grimes, W. Hale, F. Hames, J. Hanvey, F. W. Harden, J. W. Hardy, G. B. Hemingway, Jr., 0. Hewitt, B. Humphreys, A. D. Jacobberger, A. F. Johnson, J. B. Johnson, H. W. Kale II, L. Kiff, J. N. Layne, R. Lee, R. Loftin, F. E. Lohrer, J. Loughlin, the late C. R. Mason, J. McKinlay, J. R. Miller, R. R. Miller, B. -

Arctic Fox Migrations in Manitoba

Arctic Fox Migrations in Manitoba ROBERT E. WRIGLEY and DAVID R. M. HATCH1 ABSTRACT. A review is provided of the long-range movements and migratory behaviour of the arctic fox in Manitoba. During the period 1919-75, peaks in population tended to occur at three-year intervals, the number of foxes trapped in any particular year varying between 24 and 8,400. Influxes of foxes into the boreal forest were found to follow decreases in the population of their lemming prey along the west coast of Hudson Bay. One fox was collected in 1974 in the aspen-oak transition zone of southern Manitoba, 840 km from Hudson Bay and almost 1000 km south of the barren-ground tundra, evidently after one of the farthest overland movements of the species ever recorded in North America. &UMfi. Les migrations du renard arctique au Manitoba. On prksente un compta rendu des mouvements B long terme et du comportement migrateur du renard arctique au Manitoba. Durant la p6riode de 1919-75, les maxima de peuplement tendaient fi revenir B des intervalles de trois ans, le nombre de renards pris au pihge dans une ann6e donn6e variant entre 24 et 8,400. On a constat6 que l'atiiux de renards dans la for& bor6ale suivait les diminutions de population chezleurs proies, les lemmings, en bordure de la côte oceidentale de la mer d'Hudson. En 1974, on a trouv6 un renard dans la zone de transition de trembles et de ch€nes, dans le sud du Manitoba, B 840 kilomhtres de la mer d'Hudson et fi presque 1000 kilomh- tres au sud des landes de la tundra. -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania. -

Acorn Dispersal by California Scrub-Jays in Urban Sacramento, California Daniel A

ACORN DISPERSAL BY CALIFORNIA SCRUB-JAYS IN URBAN SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA DANIEL A. AIROLA, Conservation Research and Planning, 114 Merritt Way, Sac- ramento, California 95864; [email protected] ABSTRACT: California Scrub-Jays (Aphelocoma californica) harvest and cache acorns as a fall and winter food resource. In 2017 and 2018, I studied acorn caching by urban scrub-jays in Sacramento, California, to characterize oak and acorn resources, distances jays transport acorns, caching’s effects on the jay’s territoriality, numbers of jays using acorn sources, and numbers of acorns distributed by jays. Within four study areas, oak canopy cover was <1%, and only 19% of 126 oak trees, 92% of which were coast live oaks (Quercus agrifolia), produced acorns. Jays transported acorns for ≥117 days. Complete (28%) and partially recorded (72%) flights from acorn sources to caching sites averaged 160 m and ranged up to 670 m. Acorn- transporting jays passed at tree-top level above other jays’ territories without eliciting defense. At least 20 scrub-jays used one acorn source in one 17.5-ha area, and ≥13 jays used another 4.7-ha area. Jays cached an estimated 6800 and 11,000 acorns at two study sites (mean 340 and 840 acorns per jay, respectively), a rate much lower than reported in California oak woodlands, where harvest and caching are confined within territories. The lower urban caching rate may result from a scarcity of acorns, the time required for transporting longer distances, and the availability of alternative urban foods. Oaks originating from acorns planted by jays benefit diverse wildlife and augment the urban forest.