Arctic Fox Migrations in Manitoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ecology and Management of Moose in North America

THE ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF MOOSE IN NORTH AMERICA Douglas H. PIMLOTT Department of Lands and Forests, Maple, Ontario, Canada Concepts of the status, productivity and management of North American moose (Alces alces) have changed greatly during the past decade. The rapidity of the change is illustrated by the published record. TUFTS (1951) questioned, « Is the moose headed for extinc tion ? » and discussed the then current belief that moose populations had seriously declined across much of the continent. Five years later, PETERSON (1955: 217) stated, « It appears almost inevitable that the days of unlimited hunting for moose must soon pass from most of North America. » He also suggested (1955 : 216) that a kill of 12 to 25 per cent of the adult population is the highest that would permit the maintenance of the breeding population. Four years later, I showed (PIMLOTT, 1959a) that moose in Newfoundland could sustain a kill of twice the magnitude suggested by Peterson. I also suggested (PIMLOTT, 1959b) that the North American moose kill could be very greatly increased-in spite of progressive liberalization of hunting regulations over much of Canada and a marked increase in annual kill. It is not realistic to assume that the status of the species has changed, within the decade, from threatened extinction to annual harvests of approximately 40,000 and potential harvests of two to three times that number. Although moose populations have increased in some areas since 1950, there is little doubt that the changed think ing about moose management is more the result of the increase in knowledge than of any other factor. -

Laurentide Ice-Flow Patterns: a Historical Review, and Implications of the Dispersal of Belcher Islands Erratics"

Article "Laurentide Ice-Flow Patterns: A Historical Review, and Implications of the Dispersal of Belcher Islands Erratics" Victor K. Prest Géographie physique et Quaternaire, vol. 44, n° 2, 1990, p. 113-136. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032812ar DOI: 10.7202/032812ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 12 février 2017 05:36 Géographie physique et Quaternaire, 1990, vol. 44, n°2, p. 113-136, 29 fig., 1 tabl LAURENTIDE ICE-FLOW PATTERNS A HISTORIAL REVIEW, AND IMPLICATIONS OF THE DISPERSAL OF BELCHER ISLAND ERRATICS Victor K. PREST, Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E8. ABSTRACT This paper deals with the evo Archean upland. Similar erratics are common en se fondant sur la croissance glaciaire vers lution of ideas concerning the configuration of in northern Manitoba in the zone of confluence l'ouest à partir du Québec-Labrador. -

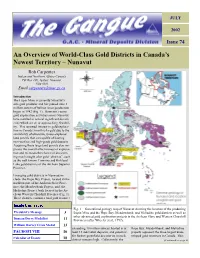

An Overview of World-Class Gold Districts in Canada's Newest

JULY 2002 Issue 74 An Overview of World-Class Gold Districts in Canada’s Newest Territory – Nunavut Rob Carpenter Indian and Northern Affairs Canada PO Box 100, Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 0H0 Email [email protected] Introduction The Lupin Mine is currently Nunavut’s sole gold producer and has poured over 3 million ounces of bullion since production began in 1982 (Fig. 1). However, recent gold exploration activities across Nunavut have resulted in several significant discov- eries which are at, or approaching, feasibil- ity. This renewed interest in gold explora- tion in Canada’s north is largely due to the availability of extensive, under-explored land parcels that are capable of hosting near-surface and high-grade gold deposits. Acquiring these large land parcels also im- proves the overall effectiveness of explora- tion and increases the chance of discover- ing much sought after gold “districts”, such as the well known Timmins and Kirkland Lake gold districts of the Archean Superior Province. Emerging gold districts in Nunavut in- clude: the Hope Bay Project, located in the northern part of the Archean Slave Prov- ince; the Meadowbank Project, and; the Meliadine Project, both located in the Ar- chean Western Churchill Province (Fig. 1). These districts contain a total gold resource ,QVLGH WKLV LVVXH Fig. 1 – Generalized geology map of Nunavut showing the location of the producing President’s Message 3 Lupin Mine and the Hope Bay, Meadowbank, and Meliadine gold districts as well as other advanced gold exploration projects in the Archean Slave and Western Churchill Duncan Derry Medallist 11 Provinces (after Wheeler et al., 1997). -

PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENTS 9.—Provinces and Territories Of

PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENTS 83 9.—Provinces and Territories of Canada, with present Areas, Dates of Admission to Confederation and Legislative Process by which this was effected. Present Area (square miles). Province, Date of Territory Admission Legislative Process. or District. or Creation. Land. Water. Total. Ontario July 1, 1867[Ac t of Imperial Parliament—The] 357,962 49,300 407,2621 Quebec " 1, 1867J British North America Act, 18671 571,004 23,430 594,4342 Nova Scotia " 1, 1867 (30-31 Vict., c. 3), and Imperial! 20,743 685 21,428 New Brunswick.. " 1, 1867[ Order in Council of May 22,1867. J 27,710 275 27,985 Manitoba " 15, 1870Manitob a Act, 1870 (33 Vict., c. 3) and Imperial Order in Council, June 23, 1870 224,777 27,055 251,8323 British Columbia. " 20, 1871Imperia l Order in Council, May 16,1871 349,970 5,885 355,855 P.E. Island " 1, 1873Imperia l Order in Council, June 26,1873 2,184 2,184 Saskatchewan Sept. 1, 1905Saskatchewa n Act, 1905 (4-5 Edw. VII, c. 42) 237,975 13,725 251,700* Alberta. " 1, 1905Albert a Act, 1905 (4-5 Edw. VII, c. 3). 248,80J 6,485 255,285* Yukon.. June 13, 1898Yuko n Territory Act, 1898 (61 Vict., c.6) 205,346 1,730 207,076 Mackenzie. Jan. 1, 1920 493,225 34,265 527,490 s Keewatin.. " 1, 1920-Orde r in Council, Mar. 16,1918. 218,460 9,700 228,160s Franklin... " 1, 1920 546,532 7,500 554,0325 Total. 3,504,688 180,035 3,684,733 1 The area of Ontario was extended by the Canada (Ontario Boundary) Act, 1889, and the Ontario Boundaries Extension Act, 1912 (2 Geo. -

Barren-Ground Caribouin A

SCIENCE ADVANCES | RESEARCH ARTICLE APPLIED ECOLOGY Copyright © 2018 The Authors, some Undermining subsistence: Barren-ground caribou in a rights reserved; exclusive licensee “tragedy of open access” American Association for the Advancement 1 2 3 of Science. No claim to Brenda L. Parlee, * John Sandlos, David C. Natcher original U.S. Government Works. Distributed Sustaining arctic/subarctic ecosystems and the livelihoods of northern Indigenous peoples is an immense challenge under a Creative “ ” ’ amid increasing resource development. The paper describes a tragedy of open access occurring in Canada s north Commons Attribution as governments open up new areas of sensitive barren-ground caribou habitat to mineral resource development. NonCommercial Once numbering in the millions, barren-ground caribou populations (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus/Rangifer License 4.0 (CC BY-NC). tarandus granti) have declined over 70% in northern Canada over the last two decades in a cycle well understood by northern Indigenous peoples and scientists. However, as some herds reach critically low population levels, the impacts of human disturbance have become a major focus of debate in the north and elsewhere. A growing body of science and traditional knowledge research points to the adverse impacts of resource development; however, management efforts have been almost exclusively focused on controlling the subsistence harvest of northern Indigenous peoples. These efforts to control Indigenous harvesting parallel management practices during pre- vious periods of caribou population decline (for example, 1950s) during which time governments also lacked Downloaded from evidence and appeared motivated by other values and interests in northern lands and resources. As mineral re- source development advances in northern Canada and elsewhere, addressing this “science-policy gap” problem is critical to the sustainability of both caribou and people. -

Medicine in Manitoba

Medicine in Manitoba THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS /u; ROSS MITCHELL, M.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY LIBRARY FR OM THE ESTATE OF VR. E.P. SCARLETT Medic1'ne in M"nito/J" • THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS By ROSS MITCHELL, M. D. .· - ' TO MY WIFE Whose counsel, encouragement and patience have made this wor~ possible . .· A c.~nowledg ments THE LATE Dr. H. H. Chown, soon after coming to Winnipeg about 1880, began to collect material concerning the early doctors of Manitoba, and many years later read a communication on this subject before the Winnipeg Medical Society. This paper has never been published, but the typescript is preserved in the medical library of the University of Manitoba and this, together with his early notebook, were made avail able by him to the present writer, who gratefully acknowledges his indebtedness. The editors of "The Beaver": Mr. Robert Watson, Mr. Douglas Mackay and Mr. Clifford Wilson have procured informa tion from the archives of the Hudson's Bay Company in London. Dr. M. T. Macfarland, registrar of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba, kindly permitted perusal of the first Register of the College. Dr. J. L. Johnston, Provincial Librarian, has never failed to be helpful, has read the manuscript and made many valuable suggestions. Mr. William Douglas, an authority on the Selkirk Settlers and on Free' masonry has given precise information regarding Alexander Cuddie, John Schultz and on the numbers of Selkirk Settlers driven out from Red River. Sheriff Colin Inkster told of Dr. Turver. Personal communications have been received from many Red River pioneers such as Archbishop S. -

NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas Cultural Heritage and Interpretative

NTI IIBA for Phase I: Cultural Heritage Resources Conservation Areas Report Cultural Heritage Area: McConnell River and Interpretative Migratory Bird Sanctuary Materials Study Prepared for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 1 May 2011 This Cultural Heritage Report: McConnell River Migratory Bird Sanctuary (Arviat) is part of a set of studies and a database produced for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. as part of the project: NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas, Cultural Resources Inventory and Interpretative Materials Study Inquiries concerning this project and the report should be addressed to: David Kunuk Director of Implementation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 3rd Floor, Igluvut Bldg. P.O. Box 638 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 E: [email protected] T: (867) 975‐4900 Project Manager, Consulting Team: Julie Harris Contentworks Inc. 137 Second Avenue, Suite 1 Ottawa, ON K1S 2H4 Tel: (613) 730‐4059 Email: [email protected] Cultural Heritage Report: McConnell River Migratory Bird Sanctuary (Arviat) Authors: Philip Goldring, Consultant: Historian and Heritage/Place Names Specialist (primary author) Julie Harris, Contentworks Inc.: Heritage Specialist and Historian Nicole Brandon, Consultant: Archaeologist Luke Suluk, Consultant: Inuit Cultural Specialist/Archaeologist Frances Okatsiak, Consultant: Collections Researcher Note on Place Names: The current official names of places are used here except in direct quotations from historical documents. Throughout the document Arviat refers to the settlement established in the 1950s and previously known as Eskimo Point. Names of -

Comparative Effects on Plants of Caribou/Reindeer, Moose and White-Tailed Deer Herbivory MICHEL CRÊTE,1 JEAN-PIERRE OUELLET2 and LOUIS LESAGE3

ARCTIC VOL. 54, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 2001) P. 407– 417 Comparative Effects on Plants of Caribou/Reindeer, Moose and White-Tailed Deer Herbivory MICHEL CRÊTE,1 JEAN-PIERRE OUELLET2 and LOUIS LESAGE3 (Received 15 May 2000; accepted in revised form 21 February 2001) ABSTRACT. We reviewed the literature reporting negative or positive effects on vegetation of herbivory by caribou/reindeer, moose, and white-tailed deer in light of the hypothesis of exploitation ecosystems (EEH), which predicts that most of the negative impacts will occur in areas where wolves were extirpated. We were able to list 197 plant taxa negatively affected by the three cervid species, as opposed to 24 that benefited from their herbivory. The plant taxa negatively affected by caribou/reindeer (19), moose (37), and white-tailed deer (141) comprised 5%, 9%, and 11% of vascular plants present in their respective ranges. Each cervid affected mostly species eaten during the growing season: lichens and woody species for caribou/reindeer, woody species and aquatics for moose, and herbs and woody species for white-tailed deer. White-tailed deer were the only deer reported to feed on threatened or endangered plants. Studies related to damage caused by caribou/reindeer were scarce and often concerned lichens. Most reports for moose and white-tailed deer came from areas where wolves were absent or rare. Among the three cervids, white- tailed deer might damage the most vegetation because of its smaller size and preference for herbs. Key words: caribou, forage, herbivory, moose, reindeer, vegetation, white-tailed deer, wolf RÉSUMÉ. À la lumière de l’hypothèse de l’exploitation des écosystèmes (EEH), nous avons examiné les publications qui mentionnent les effets négatifs ou positifs, sur la végétation, du broutement du caribou/renne, de l’orignal et du cerf de Virginie. -

Taiga Shield Ecozone

.9t Perspective on Canatia's f£cosgstems YIn OVerview oftfie 'Ierrestria{ and !Mari:ne t£cazones Prepared for the Canadian Council on Ecological Areas Ottawa, Ontario KIA OH3 llTitten by Ed B. Wiken, David Gauthier, Ian Marshall, Ken Lawton and Harry Hirvonen CCEA Occasional Papers (September 1996) 1996, NO. 14 ( ( Table of Contents ( ( Prelude ........................................................................................... iv ( vi Acknowledgements ....................................................................... t Section 1 ( Introduction .................................................................................. 1 ( Section 2 ( Defining Ecozones and Ecosystems ............................................. 2 ( Section 3 ( The Terrestrial Ecozones of Canada ........................................ 11 ( Arctic Cordillera Ecozone ............................................................ 12 Northern Arctic Ecozone .............................................................. 15 ( Southern Arctic Ecozone .............................................................. 18 C Taiga Plains Ecozone .................................................................... 22 ( Taiga Shield Ecozone ................................................................... 25 ( Taiga Cordillera Ecozone ............................................................. 28 Hudson Plains Ecozone ................................... :............................ 31 ( Boreal Plains Ecozone ................................................................. -

Wildlife Conservation in the North: Historic Approaches and Their Consequences; Seeking Insights for Contemporary Resource Management

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Conferences Canadian Parks for Tomorrow 2008 Wildlife Conservation in the North: Historic Approaches and their Consequences; Seeking Insights for Contemporary Resource Management Sandlos, John Sandlos, J. "Wildlife Conservation in the North: Historic Approaches and their Consequences; Seeking Insights for Contemporary Resource Management." Paper Commissioned for Canadian Parks for Tomorrow: 40th Anniversary Conference, May 8 to 11, 2008, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/46878 conference proceedings Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Wildlife Conservation in the North: Historic Approaches and their Consequences; Seeking Insights for Contemporary Resource Management John Sandlos Assistant Professor Department of History Memorial University of Newfoundland St. John’s, Newfoundland A1C 5S7 tel: 709-737-2429 fax: 709 [email protected] Abstract: Recent studies in the field of Canadian environmental history have suggested that early state wildlife conservation programs in northern Canada were closely tied to broader efforts to colonize the social and economic lives of the region’s Aboriginal people. Although it is tempting to draw a sharp distinction between the “bad old days” of autocratic conservation and the more inclusive approaches of the enlightened present such as co-management and the incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) into wildlife management decision-making, this paper will argue that many conflicts -

Breeds on Islands and Along Coasts of the Chukchi and Bering

FAMILY PTEROCLIDIDAE 217 Notes.--Also known as Common Puffin and, in Old World literature, as the Puffin. Fra- tercula arctica and F. corniculata constitutea superspecies(Mayr and Short 1970). Fratercula corniculata (Naumann). Horned Puffin. Mormon corniculata Naumann, 1821, Isis von Oken, col. 782. (Kamchatka.) Habitat.--Mostly pelagic;nests on rocky islandsin cliff crevicesand amongboulders, rarely in groundburrows. Distribution.--Breedson islandsand alongcoasts of the Chukchiand Bering seasfrom the DiomedeIslands and Cape Lisburnesouth to the AleutianIslands, and alongthe Pacific coast of western North America from the Alaska Peninsula and south-coastal Alaska south to British Columbia (QueenCharlotte Islands, and probablyelsewhere along the coast);and in Asia from northeasternSiberia (Kolyuchin Bay) southto the CommanderIslands, Kam- chatka,Sakhalin, and the northernKuril Islands.Nonbreeding birds occurin late springand summer south along the Pacific coast of North America to southernCalifornia, and north in Siberia to Wrangel and Herald islands. Winters from the Bering Sea and Aleutians south, at least casually,to the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (from Kure east to Laysan), and off North America (rarely) to southern California;and in Asia from northeasternSiberia southto Japan. Accidentalin Mackenzie (Basil Bay); a sight report for Baja California. Notes.--See comments under F. arctica. Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas). Tufted Puffin. Alca cirrhata Pallas, 1769, Spic. Zool. 1(5): 7, pl. i; pl. v, figs. 1-3. (in Mari inter Kamtschatcamet -

The Boundaries of Canada

THE BOUNDARIES OF CANADA A. F. N. POOLE* Toronto 1. General Introduction . Throughout its history Canada has been concerned with both international and internal boundary problems, and the purpose of this article is to present the legal authorities by which they were settled. The international boundaries were finally determined early in this century, and this article does not cover such secondary problems as the utilization of international rivers,' particularly the Columbia,' St. Lawrence' and Niagara`' Rivers, the Air De- fence Identification Zones,' the use of the contiguous zone for fisheries conservation' and the status in international law of Hud- *A. F. N. Poole, M.A. (Oxon.), LL.B., Toronto . 1 See Robert A. MacKay, The International Joint Commission between the United States and Canada (1928), 22 Am. J. of Int. L. 292 ; Clyde Eagleton, The Use of the Waters of International Rivers (1955), 33 Can. Bar Rev. 1018 ; Robert Day Scott, The Canadian-American Boundary Waters Treaty : Why Article II? (1958), 36 Can. Bar Rev . 511 ; L. M . Bloomfield and G. F. Fitzgerald, Boundary Waters Problems of Canada and the United States (1958) ; William L. Griffin, The Use of the Waters of International Drainage Basins under Customary International Law (1959), 53 Am. J. of Int . L. 50 ; Jacob Austin, Canadian-United States Practice and Theory Respecting the International Law of International Rivers (1959), 37 Can. Bar Rev . 393 ; Ludwik A. Leclaff, United States River Treaties (1963), 31 Fordham L. Rev. 697 ; L.J. Bouchez, The Fixing of Boundaries in International Boundary Rivers (1963), 12 Int . & Comp . L.Q. 789. a See C.