Jordan's Encounter with Shiism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel/Lebanon out of All Proportion - Civilians Bear the Brunt of the War

Israel/Lebanon Out of all proportion - civilians bear the brunt of the war AI Index: MDE 02/033/2006 Amnesty International November 2006 2 Israel/Lebanon: Out of all proportion - civilians bear the brunt of the war TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Introduction..................................................................................................2 Chapter 2: International law as it applies to the war......................................................7 International humanitarian law...................................................................................8 International human rights law.................................................................................13 International criminal law ........................................................................................14 Chapter 3: Israel’s attacks and their rationale..............................................................17 Chapter 4: Civilians under fire.....................................................................................28 Trapped and terrorized .............................................................................................28 Killed in their homes................................................................................................31 Attacked in flight......................................................................................................41 Medical vehicles and humanitarian -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Maternal Mortality Ratio in Lebanon in 2008: a Hospital-Based Reproductive Age Mortality Survey (Ramos)

MATERNAL MORTALITY RATIO IN LEBANON IN 2008: A HOSPITAL-BASED REPRODUCTIVE AGE MORTALITY SURVEY (RAMOS) Salim Adib, MD, DrPH Professor of Epidemiology and Public Heath Faculty of Medicine Saint-Joseph University Beirut- Lebanon Beirut- Lebanon January 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: This proposal is based on an earlier document prepared by Dr. Ziad Mansour, Technical Officer, WR Office in Beirut. Fieldwork was conducted by Drs. Tony Ghanem, Miche Fahad, Ralph Karam, Chucrallah Chamandi, and was coordinated by Dr. Samer Abi-Chaker. Mr. Elie Hobeika was instrumental in data entry, analysis and report preparation. The project was also facilitated through the intervention of Mr. Mohammad-Ali Hamandi and Mrs. Rita Rahbany-Saad on behalf of the Syndicate of Private Hospitals and Ms. Hilda Harb on behalf of the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health (MOPH). MOPH Director-General, Dr. Walid Ammar was the senior advisor on the project. Funding was provided through the WR Office in Beirut. MATERNAL MORTALITY RATIO IN LEBANON IN 2008: A HOSPITAL-BASED REPRODUCTIVE AGE MORTALITY SURVEY (RAMOS) A. INTRODUCTION A1. Rationale The complexity of ascertaining maternal deaths makes it difficult for many low income countries to measure the levels of maternal mortality, hence the lack of valid data on such avoidable deaths. A report prepared by international agencies (1) has recently assigned Lebanon to the group H of countries with “no national data on maternal mortality”. As a result, an arbitrary equation was used to determine that Lebanon’s maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in 2005 was 150 per 100,000 live births. The Lebanese government disputes this classification and its consequences. -

The Notion and Significance of Ma[Rifa in Sufism

Journal of Islamic Studies 13:2 (2002) pp. 155–181 # Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies 2002 THE NOTION AND SIGNIFICANCE OF MA[RIFA IN SUFISM REZA SHAH-KAZEMI London At the heart of the Sufi notion of ma[rifa there lies a paradox that is as fruitful in spiritual terms as it is unfathomable on the purely mental plane: on the one hand, it is described as the highest knowledge to which the individual has access; but on the other, the ultimate content of this knowledge so radically transcends the individual that it comes to be described in terms of ‘ignorance’. In one respect, it is said to be a light that illumines and clarifies, but in another respect its very brilliance dazzles, blinds, and ultimately extinguishes the one designated as a ‘knower’ (al-[a¯rif ).1 This luminous knowledge that demands ‘unknowing’ is also a mode of being that demands effacement; and it is the conjunction between perfect knowledge and pure being that defines the ultimate degree of ma[rifa. Since such a conjunction is only perfectly realized in the undifferentiated unity of the Absolute, it follows that it can only be through the Absolute that the individual can have access to this ultimate degree of ma[rifa, thus becoming designated not as al-[a¯rif, tout court, but as al-[a¯rif bi-Lla¯h: the knower through God. The individual is thus seen as participating in Divine knowledge rather than possessing it, the attribute of knowledge pertaining in fact to God and not himself. In this light, the definition of tasawwuf given by al-Junayd (d. -

Books on Logic (Manṭiq) and Dialectics (Jadal)

_full_journalsubtitle: An Annual on the Visual Cultures of the Islamic World _full_abbrevjournaltitle: MUQJ _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0732-2992 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 2211-8993 (online version) _full_issue: 1 _full_volume: 14 _full_pubyear: 2019 _full_journaltitle: Muqarnas Online _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_fpage: 000 _full_lpage: 000 _full_articleid: 10.1163/22118993_01401P008 _full_alt_author_running_head (change var. to _alt_author_rh): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (change var. to _alt_arttitle_rh): Manuscripts on Logic (manṭiq) and Dialectics (jadal) Manuscripts on Logic (manṭiq) and Dialectics (jadal) 891 KHALED EL-ROUAYHEB BOOKS ON LOGIC (MANṭIQ) AND DIALECTICS (JADAL) The ordering of subjects in the palace library inventory Secrets in Commenting upon the Dawning of Lights); prepared by ʿAtufi seems to reflect a general sense of the fourth entry has “The Commentary on the Logic of rank. Logic and dialectics appear toward the end of the Maṭāliʿ al-anwār, entitled Lawāmiʿ al-asrār,” again with inventory, suggesting that they were ranked relatively no indication of the author. low. Nevertheless, these disciplines were regularly stud- To take another example, ʿAtufi has four entries on ied in Ottoman colleges (madrasas). The cataloguer the same Quṭb al-Din al-Razi’s commentary on another ʿAtufi himself contributed to them, writing a commen- handbook of logic, al-Risāla al-Shamsiyya (The Epistle tary on Īsāghūjī (Introduction), the standard introduc- for Shams al-Din) by Najm al-Din al-Katibi (d. 1276). The tory handbook -

Usaid/Lebanon Lebanon Industry Value Chain

USAID/LEBANON LEBANON INDUSTRY VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT (LIVCD) PROJECT LIVCD QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT - YEAR 3, QUARTER 4 JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2015 FEBRUARY 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. CONTENTS ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................3 YEAR 3 QUARTER 4: JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30 2015 ............................................................... 4 PROJECT OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 4 EXCUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................... 4 QUARTERLY REPORT structure ...................................................................................................................... 5 1. LIVCD YEAR 3 QUARTER 4: RESULTS (RESULTS FRAMEWORK & PERFORMANCE INDICATORS) ................................................................................................................................6 Figure 1: LIVCD Results framework and performance indicators ......................................................... 7 Figure 2: Results achieved against targets .................................................................................................... 8 Table 1: Notes on results achieved .................................................................................................................. -

Abd Al-Karim Al-Jili

‛ABD AL-KAR ĪM AL-JĪLĪ: Taw ḥīd, Transcendence and Immanence by NICHOLAS LO POLITO A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The present thesis is an attempt to understand ‛Abd Al-Kar īm Al-Jīlī’s thought and to illustrate his original contribution to the development of medieval Islamic mysticism. In particular, it maintains that far from being an obscure disciple of Ibn ‛Arab ī, Al-Jīlī was able to overcome the apparent contradiction between the doctrinal assumption of a transcendent God and the perception of divine immanence intrinsic in God’s relational stance vis-à-vis the created world. To achieve this, this thesis places Al-Jīlī historically and culturally within the Sufi context of eighth-ninth/fourteenth-fifteenth centuries Persia, describing the world in which he lived and the influence of theological and philosophical traditions on his writings, both from within and without the Islamic world. -

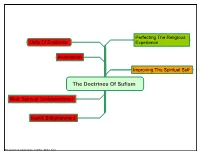

The Doctrines of Sufism

Perfecting The Religious Unity Of Existence Experience Annihilation Improving The Spiritual Self The Doctrines Of Sufism Wali: Spiritual Guide/sainthood Kashf: Enlightenment The doctrines of sufism.mmap • 3/4/2006 • Mindjet Team Emphasizes perception, maarifa leading to direct knowledge of Self and God, and Sufism uses the heart as its medium Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as The Context: (The Approaches To its medium, and subjects reason to Faith And Understanding) Kalam revelation Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as Philosophy its medium AL BAQARA Al Junayd Al Hallaj Annihilation By Examples Taqwa: Piety Sobriety The Goals Of The Spiritual Journey Paradox and biwelderment Intoxication QAAF The Consequence Of Annihilation Annihilation Abu Bakr (RAA): Incapacity to perceive is perception Perplexity Results from the negation in the first part of the Shahada (fana) AL HADEED And from the affirmation of the Living the Shahada subsistence in the second part of the Shahada: (Baqa) Be witness to the divine reality, and eliminate the egocentric self Living the Tawheed The Motivation For Annihilation Start as a stone Be shuttered by the divine light of the Self transformation divine reality you witness Emerge restructed as a jewel The Origins Of Annihilation AL RAHMAN Annihilation.mmap • 3/6/2006 • Mindjet Team Born and Raised in Baghdad (died in 910 or 198 H) His education focused on Fiqh and Hadith He studied under the Jurist Abu Thawr: An extraordinary jurist started as a Hanafii, then followed the Shafi school once al Imam Al Shafi came to Baghdad. -

Political Sectarianism in Lebanon Loulwa Murtada

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2018 Aversive Visions of Unanimity: Political Sectarianism in Lebanon Loulwa Murtada Recommended Citation Murtada, Loulwa, "Aversive Visions of Unanimity: Political Sectarianism in Lebanon" (2018). CMC Senior Theses. 1941. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1941 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Aversive Visions of Unanimity: Political Sectarianism in Lebanon Submitted to Professor Roderic Camp By Loulwa Murtada For Senior Thesis Fall 2017/ Spring 2018 23 April 2018 Abstract Sectarianism has shaped Lebanese culture since the establishment of the National Pact in 1943, and continues to be a pervasive roadblock to Lebanon’s path to development. This thesis explores the role of religion, politics, and Lebanon’s illegitimate government institutions in accentuating identity-based divisions, and fostering an environment for sectarianism to emerge. In order to do this, I begin by providing an analysis of Lebanon’s history and the rise and fall of major religious confessions as a means to explore the relationship between power-sharing arrangements and sectarianism, and to portray that sectarian identities are subject to change based on shifting power dynamics and political reforms. Next, I present different contexts in which sectarianism has amplified the country’s underdevelopment and fostered an environment for political instability, foreign and domestic intervention, lack of government accountability, and clientelism, among other factors, to occur. A case study into Iraq is then utilized to showcase the implications of implementing a Lebanese-style power-sharing arrangement elsewhere, and further evaluate its impact in constructing sectarian identities. -

A Study on Sayyid Qutb a Dissertation Submitted To

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO READING A RADICAL THINKER: A STUDY ON SAYYID QUTB A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY LAITH S. SAUD CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2017 Table of Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................................. iii Chapter One: Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Biography ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter Review .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter Two: Reading Qutb Theologically; Toward a Method for Reading an Islamist ............................................................................................................................................................................ 10 The Current State of Inquiries on Qutb: The Fundamentalist par excellence ............................. 11 Theology, Epistemology, and Logic: Toward a Methodology .............................................................. 17 What is Qutb’s General Cosmology? ............................................................................................................. -

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections Foreword This study on the political party mapping in Lebanon ahead of the 2018 elections includes a survey of most Lebanese political parties; especially those that currently have or previously had parliamentary or government representation, with the exception of Lebanese Communist Party, Islamic Unification Movement, Union of Working People’s Forces, since they either have candidates for elections or had previously had candidates for elections before the final list was out from the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities. The first part includes a systematic presentation of 27 political parties, organizations or movements, showing their official name, logo, establishment, leader, leading committee, regional and local alliances and relations, their stance on the electoral law and their most prominent candidates for the upcoming parliamentary elections. The second part provides the distribution of partisan and political powers over the 15 electoral districts set in the law governing the elections of May 6, 2018. It also offers basic information related to each district: the number of voters, the expected participation rate, the electoral quotient, the candidate’s ceiling on election expenditure, in addition to an analytical overview of the 2005 and 2009 elections, their results and alliances. The distribution of parties for 2018 is based on the research team’s analysis and estimates from different sources. 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction .......................................................................................................