Late Eighteenth Century Painters in Malta -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/41440 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Said-Zammit, G.A. Title: The development of domestic space in the Maltese Islands from the Late Middle Ages to the second half of the Twentieth Century Issue Date: 2016-06-30 BIBLIOGRAPHY Aalen F.H.A. 1984, ‘Vernacular Buildings in Cephalonia, Ionian Islands’, Journal of Cultural Geography 4/2, 56-72. Abela G.F. 1647, Della descrittione di Malta. Malta, Paolo Bonacota. Abela J. 1997, Marsaxlokk a hundred Years Ago: On the Occasion of the Erection of Marsaxlokk as an Independent Parish. Malta, Kumitat Festi Ċentinarji. Abela J. 1999, Marsaskala, Wied il-Għajn. Malta, Marsascala Local Council. Abela J. 2006, The Parish of Żejtun Through the Ages. Malta, Wirt iż-Żejtun. Abhijit P. 2011, ‘Axial Analysis: A Syntactic Approach to Movement Network Modeling’, Institute of Town Planners India Journal 8/1, 29-40. Abler R., Adams J. and Gould P. 1971, Spatial Organization. New Jersey, Prentice- Hall. Abrams P. and Wrigley E.A. (eds.) 1978, Towns in Societies: Essays in Economic History and Historical Sociology. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Abulafia D. 1981, ‘Southern Italy and the Florentine Economy, 1265-1370’, The Economic History Review 34/3, 377-88. Abulafia D. 1983, ‘The Crown and the Economy under Roger II and His Successors’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 37, 1-14. Abulafia D. 1986, ‘The Merchants of Messina: Levant Trade and Domestic Economy’, Papers of the British School at Rome 54, 196-212. Abulafia D. 2007, ‘The Last Muslims in Italy’, Annual Report of the Dante Society 125, 271-87. -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,652 Prezz/Price €1.98 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette It-Tnejn, 28 ta’ Ġunju, 2021 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Monday, 28th June, 2021 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Notifikazzjonijiet tal-Gvern ............................................................................................. 6609 - 6617 Government Notices ......................................................................................................... 6609 - 6617 Avviżi lill-Baħħara ........................................................................................................... 6617 - 6618 Notices to Mariners .......................................................................................................... 6617 - 6618 Avviżi tal-Gvern ............................................................................................................... 6618 - 6619 Notices .............................................................................................................................. 6618 - 6619 Offerti ............................................................................................................................... 6619 - 6624 Tenders ............................................................................................................................. 6619 - 6624 Avviżi tal-Qorti ................................................................................................................ 6625 - 6648 Court Notices .................................................................................................................. -

L-Awtorità Ta' Malta Għall-Kompetizzjoni U Għall

L-Awtorità ta’ Malta għall-Kompetizzjoni u għall-Affarijiet tal-Konsumatur Reġistrazzjoni/Regi Belt jew raħal/Town Bini/Building Triq/Street Serial stration or village N/AL/0023/14 AFS, Triq L-Imdina, ATTARD QH4264/AFS28411 N/AP/0008/10 The Ivies, Block A, Triq il-Mosta, ATTARD A993 N/AP/0056/08 Windsor Court, Triq Kananea, ATTARD A649 N/AU/0027/11 350, San Salvatore, Triq il-Linja, ATTARD 1101003 N/AN/0028/09 Trouvaille Apartments, Triq il-Pruna, ATTARD AC15254 N/AU/0012/11 New Building c/o AM Development, Triq Lorenzo Manche`, ATTARD 103003 N/AU/0013/11 New Building c/o AM Development, Triq il-Fikus, ATTARD 103001 N/AU/0017/11 Ecuador, Block 1, Triq il-Faqqiegh, ATTARD 27107-C N/AU/0018/11 Ecuador, Block 2, Triq il-Faqqiegh, ATTARD CG450B N/AU/0023/11 4, Flora Mansions, Triq l-Ghenba, ATTARD 104011 E/AP/0011/02 3, C + M Marketing Limited, Triq Ferdinandu Inglott, ATTARD IEP1285 N/AA/0015/10 In Design Malta Ltd, Triq Haz-Zebbug, ATTARD 106-10 ADV N/AU/0021/06 Mount Carmel, Jean Antide Ward, Triq Notabile, ATTARD 9532 N/AJ/0006/07 The Gold Market, Triq l-Imdina, ATTARD 10.94/27/05 N/AU/0004/11 Mount Carmel, Triq Notabile, ATTARD 30344 N/AI/0072/10 Villa Emmanuel, Triq il-Belt Valletta, ATTARD MEK 085_07 / 10944331 N/AN/0023/09 New Block, Triq il-Mosta, ATTARD AC-40471 N/AN/0018/09 Highland Mension, Triq Mario Cortis, ATTARD AC-30089 APRIL 2021 1 L-Awtorità ta’ Malta għall-Kompetizzjoni u għall-Affarijiet tal-Konsumatur E/AL/0034/02 Office of the President, San Anton Palace, ATTARD EXM 4462755 N/AP/0009/10 The Ivies, Block B, Triq il-Mosta, -

St-Paul-Faith-Iconography.Pdf

An exhibition organized by the Sacred Art Commission in collaboration with the Ministry for Gozo on the occasion of the year dedicated to St. Paul Exhibition Hall Ministry for Gozo Victoria 24th January - 14th February 2009 St Paul in Art in Gozo c.1300-1950: a critical study Exhibition Curator Fr. Joseph Calleja MARK SAGONA Introduction Artistic Consultant Mark Sagona For many centuries, at least since the Late Middle Ages, when Malta was re- Christianised, the Maltese have staunchly believed that the Apostle of the Gentiles Acknowledgements was delivered to their islands through divine intervention and converted the H.E. Dr. Edward Fenech Adami, H.E. Tommaso Caputo, inhabitants to Christianity, thus initiating an uninterrupted community of 1 Christians. St Paul, therefore, became the patron saint of Malta and the Maltese H.E. Bishop Mario Grech, Hon. Giovanna Debono, called him their 'father'. However, it has been amply and clearly pointed out that the present state of our knowledge does not permit an authentication of these alleged Mgr. Giovanni B. Gauci, Arch. Carmelo Mercieca, Arch. Tarcisio Camilleri, Arch. Salv Muscat, events. In fact, there is no historic, archaeological or documentary evidence to attest Arch. Carmelo Gauci, Arch. Frankie Bajada, Arch. Pawlu Cardona, Arch. Carmelo Refalo, to the presence of a Christian community in Malta before the late fourth century1, Arch. {u\epp Attard, Kapp. Tonio Galea, Kapp. Brian Mejlaq, Mgr. John Azzopardi, Can. John Sultana, while the narrative, in the Acts of the Apostles, of the shipwreck of the saint in 60 AD and its association with Malta has been immersed in controversy for many Fr. -

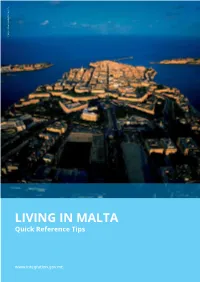

LIVING in MALTA Quick Reference Tips

image: www.viewingmalta.com LIVING IN MALTA Quick Reference Tips www.integration.gov.mt This information brochure is being published by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in collaboration with the Ministry for Social Dialogue, Consumer Affairs, and Civil Liberties (MSDC) and funded by the Integration Fund of the European Union (EU). It is intended for third country nationals (TCNs) residing in Malta with the aim of providing information regarding entry and residence, citizenship, work, social security, health, social welfare services, education and accommodation. image: www.viewingmalta.com ENTRY AND RESIDENCE REQUIREMENTS The Immigration Act (Cap 217) regulates entry and permanence in Malta of non-Maltese citizens, as well as the conditions for residence. Entry Conditions TCNs who wish to enter into Malta are able to do so under the following circumstances: 1. Possess a valid Schengen visa or a national visa or are exempted from being in possession of such a visa in accordance with the relative EU Regulation. 2. Possess a resident permit issued by another Member State which is party to the Schengen Convention. 3. Are granted a resident permit by Malta for a specific purpose. Residence Permits The issue of residence permits is regulated by the provisions of the Immigration Act (Cap 217) or national policies. Residence permits are issued to TCNs who have been authorised to reside in Malta for a specific purpose. Each type of residence provides different rights and obligations. The following is a list of the purposes for which residence permits may be granted: • Employment • Family reunification • Self-employment • Partner • Health reasons • Exempt-person status • Economic self-sufficiency • Temporary residence • Study • Long-term residence TCNs are given residence documents in the format established by the relative Regulation. -

Trainers Manual

Together in Malta – Trainers Manual 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms 3 Introduction 4 Proposed tools for facilitators of civic orientation sessions 6 What is civic orientation? 6 The Training Cycle 6 The principles of adult learning 7 Creating a respectful and safe learning space 8 Ice-breakers and introductions 9 Living in Malta 15 General information 15 Geography and population 15 Political system 15 National symbols 16 Holidays 17 Arrival and stay in Malta 21 Entry conditions 21 The stay in the country 21 The issuance of a residence permit 21 Minors 23 Renewal of the residence permit 23 Change of residence permit 24 Personal documents 24 Long-term residence permit in the EU and the acquisition of Maltese citizenship 24 Long Term Residence Permit 24 Obtaining the Maltese citizenship 25 Health 26 Access to healthcare 26 The National Health system 26 What public health services are provided? 28 Maternal and child health 29 Pregnancy 29 Giving Birth 30 Required and recommended vaccinations 30 Contraception 31 Abortion and birth anonymously 31 Women’s health protection 32 Prevention and early detection of breast cancer 32 Sexually transmitted diseases 32 Anti violence centres 33 FGM - Female genital mutilation 34 School life and adult education 36 IOM Malta 1 De Vilhena Residence, Apt. 2, Trejqet il-Fosos, Floriana FRN 1182, Malta Tel: +356 2137 4613 • Fax: +356 2122 5168 • E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.iom.int 2 Malta’s education system 36 School Registration 37 Academic / School Calendar 38 Attendance Control 38 -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,684 Prezz/Price €2.34 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette It-Tlieta, 17 ta’ Awwissu, 2021 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Tuesday, 17th August, 2021 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Notifikazzjonijiet tal-Gvern ............................................................................................. 8285 - 8292 Government Notices ......................................................................................................... 8285 - 8292 Avviżi tal-Pulizija ............................................................................................................ 8292 - 8293 Police Notices .................................................................................................................. 8292 - 8293 Avviżi lill-Baħħara ........................................................................................................... 8293 - 8295 Notices to Mariners .......................................................................................................... 8293 - 8295 Opportunitajiet ta’ Impjieg ............................................................................................... 8295 - 8300 Employment Opportunities .............................................................................................. 8295 - 8300 Avviżi tal-Gvern ............................................................................................................... 8300 - 8305 Notices ............................................................................................................................. -

Annual Report 2020

HERITAGE MALTA (HM) ANNUAL REPORT 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 5 Capital Works 6 Exhibitions and Events 19 Collections and Research 23 Conservation 54 Education, Publications and Outreach 64 Other Corporate 69 Visitor Statistics 75 Appendix 1 – Calendar of Events 88 Appendix 2 – Purchase of Modern and Contemporary Artworks 98 Appendix 3 – Acquisition of Natural History Specimens 100 Appendix 4 – Purchase of Items for Gozo Museum 105 Appendix 5 – Acquisition of Cultural Heritage Items 106 Foreword 2020 has been a memorable year. For all the wrong reasons, some might argue. And they could be right on several levels. However, the year that has tested the soundness and solidity of cultural heritage institutions worldwide, has also proved to be an eye-opener and a valuable teacher, highlighting a wealth of resourcefulness that we might have otherwise remained unaware of. The COVID-19 pandemic was a direct challenge to Heritage Malta’s mission of accessibility, forcing the agency first to close its doors entirely to the public and later to restrict admissions and opening hours. However, the agency was proactive and foresighted enough to be able to adapt to its new scenario. We found ourselves in a situation where cultural heritage had to visit the public, and not vice versa. We were able to achieve this thanks to our continuous investment in technology and digitisation, which enabled us to make our heritage accessible to the public virtually. In this way, we facilitated alternative access to our sites while also launching our online shop, making it possible for our clients to buy the products usually found at our retail outlets in sites and museums. -

07.06.2021 Area 1 Valletta, Floriana

07.06.2021 Area 1 Valletta, Floriana 7 Floriana Floriana Dispensary,29, Triq Vincenzo Dimech, Floriana 21233034 Area 2 Il-Ħamrun, Il-Marsa 4 National National Pharmacy, 17, Triq Santa Marija, il-Ħamrun 21225539 Collis Williams St. Venera Pharmacy, 532, Triq il-Kbira San Ġużepp, Santa Area 3 Ħal Qormi, Santa Venera 2 Collis Williams Venera 21238625 Area 4 Birkirkara, Fleur-de-Lys 5 Remedies Remedies Pharmacy, Triq Tumas Fenech, Birkirkara 21441589 Area 5 Il-Gżira, L-Imsida, Ta' Xbiex, Tal-Pietà, Gwardamanġa 8 St. Matthew St. Matthew's Pharmacy, Triq ix-Xatt, il-Gżira. 21311797 Brown's Brown's Medical Plaza Dispensing Chemists, Cass-i-Mall Buildings, Vjal ir- Area 6 San Ġwann, San Ġiljan, Is-Swieqi, Pembroke, Ta' Giorni, L-Ibraġ 14 Medical Plaza Rihan, San Ġwann 21372195 Drug Store: Anglo Maltese Dispensary Ltd. 382, Triq Manwel Dimech, Tas- Area 7 Tas-Sliema 1 Anglo-Maltese Sliema 21334627 Brown's Area 8 Ħal-Lija, Ħ'Attard, Ħal Balzan 1 St. Mary Brown's St. Mary Pharmacy, 2, Triq Antonio Schembri. Ħ'Attard 21436348 Area 9 Il-Mosta, In-Naxxar, Il-Għargħur, L-Imġarr 16 Mġarr Mġarr Pharmacy, Triq il-Kbira c/w Triq Vitale, l-Imġarr Malta 21577784 Area 10 Il-Mellieħa, San Pawl il-Baħar, Buġibba, Il-Qawra 7 Remedies Remedies Pharmacy, 111, Triq George Borg Olivier, il-Mellieħa 21523462 Area 11 Paola, Ħal Tarxien, Santa Luċija 2 Brown's Brown's Pharmacy, 45, Telgħet Raħal Ġdid, Paola 21694818 Area 12 L-Isla, Il-Birgu, Bormla, Il-Kalkara, Fgura (PO) 1 Verdala Verdala Pharmacy, 57, Triq il-Gendus Bormla 21824720 Area 13 Ħaż-Żabbar, Marsaskala, -

It-Tlettax-Il Leġiżlatura Pl 5292

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 5292 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 359 tal-15 ta’ Lulju 2020 mill-Ministru fi ħdan l-Uffiċċju tal-Prim Ministru, f’isem il-Ministru għall-Finanzi u s-Servizzi Finanzjarji. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra GOOD CAUSES FUND – GĦOTJIET/GRANTS/BENEFIĊĊJI *15820. L-ONOR CLAUDIO GRECH staqsa lill-Ministru għall-Finanzi u s-Servizzi Finanzjarji: Jista’ l-Ministru jpoġġi fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra lista dettaljata tal- għotjiet/grants/benefiċċji kollha li ngħataw taħt il-programm tal-Good Causes Fund, sena b’sena, mis-sena 2015 ‘il hawn u għal kull għotja/grant/benefiċċju, jgħid kemm kien l-ammont, min kien il-benefiċjarju, x’kien il-proġett/inizzjattiva u meta ngħatat? 01/07/2020 ONOR. EDWARD SCICLUNA: Ngħarraf lill-Onorevoli Interpellant illi l-informazzjoni mitluba qed titpoġġa fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra. Seduta Numru 359 15/07/2020 PQ 15820 Papers Laid RAĠUNI TAL- SENA BENEFIĊJARJU AMMONT GĦOTJA/GRANT/BENEFIĊĊJU 2015 St Jeanne Antide Foundation Purchase of Second Hand Car. €8,500.00 Life Still Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings 2015 Mandrake Creations €6,000.00 and Sculpture. Contribution towards participation in UEFA 2015 Hibernians Football Club (Women) €10,000.00 competion. Support to South End Core for Malta's game vs 2015 Louis Agius (South End Core) €6,000.00 Italy. Accommodation of families requiring 2015 Puttinu Cares Foundation €40,000.00 treatment in Sutton. 2015 Rabat Parish Church Installation of lift at Pastoral Centre. €5,000.00 Organisation of the International Youth 2015 Living Ability Not Disability €1,800.00 Seminar Camp. -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,607 Prezz/Price €4.68 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette It-Tlieta, 13 ta’ April, 2021 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Tuesday, 13th April, 2021 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Notifikazzjonijiet tal-Gvern ............................................................................................. 3353 - 3372 Government Notices ......................................................................................................... 3353 - 3372 Avviżi lill-Baħħara ........................................................................................................... 3372 - 3373 Notices to Mariners .......................................................................................................... 3372 - 3373 Opportunitajiet ta’ Impjieg ............................................................................................... 3373 - 3381 Employment Opportunities .............................................................................................. 3373 - 3381 Avviżi tal-Gvern ............................................................................................................... 3381 - 3422 Notices .............................................................................................................................. 3381 - 3422 Offerti ............................................................................................................................... 3422 - 3429 Tenders ............................................................................................................................ -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 19,639 Prezz/Price €3.60 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette Il-Ġimgħa, 16 ta’ Settembru, 2016 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Friday, 16th September, 2016 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Notifikazzjonijiet tal-Gvern ............................................................................................. 7237 - 7241 Government Notices ......................................................................................................... 7237 - 7241 Avviżi tal-Pulizija ............................................................................................................ 7241 - 7243 Police Notices .................................................................................................................. 7241 - 7243 Avviżi lill-Baħħara ........................................................................................................... 7243 - 7246 Notices to Mariners .......................................................................................................... 7243 - 7246 Opportunitajiet ta’ Impieg ................................................................................................ 7246 - 7263 Employment Opportunities .............................................................................................. 7246 - 7263 Avviżi tal-Gvern ............................................................................................................... 7263 - 7274 Notices .............................................................................................................................