Sir Syed Journal of Education & Social Research Description And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern -

BSW 044 Block 3 English.Pmd

BSW-044 TRIBALS IN NORTH Indira Gandhi EASTERN AND National Open University School of Social Work NORTHERN INDIA Block 3 TRIBALS OF NORTHERN INDIA UNIT 1 Tribes of Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh 5 UNIT 2 Tribes of Rajasthan, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh 16 UNIT 3 Displacement and Migration of Tribals 31 UNIT 4 Impact of Scientific Culture and Globalization 47 EXPERT COMMITTEE Prof. Virginius Xaxa Dr. Archana Kaushik Dr. Saumya Director – Tata Institute of Associate Professor Faculty Social Sciences Department of Social Work School of Social Work Uzanbazar, Guwahati Delhi University IGNOU, New Delhi Prof. Hilarius Beck Dr. Ranjit Tigga Dr. G. Mahesh Centre for Community Department of Tribal Studies Faculty Organization and Development Indian Social Institute School of Social Work Practice Lodhi Road, New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi School of Social Work Prof. Gracious Thomas Dr. Sayantani Guin Deonar, Mumbai Faculty Faculty Prof. Tiplut Nongbri School of Social Work School of Social Work Centre for the Study of Social IGNOU, New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi Systems Dr. Rose Nembiakkim Dr. Ramya Jawaharlal Nehru University Director Faculty New Delhi School of Social Work School of Social Work IGNOU, New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi COURSE PREPARATION TEAM Block Preparation Team Programme Coordinator Unit 1 & 4 Dr. Binu Sundas Dr. Rose Nembiakkim Unit 2 & 3 Mercy Vunghiamuang Director School of Social Work IGNOU PRINT PRODUCTION Mr. Kulwant Singh Assistant Registrar (P) SOSW, IGNOU August, 2018 © Indira Gandhi National Open University, 2018 ISBN-978-93-87237-74-2 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the Indira Gandhi National Open University. -

The Importance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 32 Number 1 Ladakh: Contemporary Publics and Politics Article 13 No. 1 & 2 8-1-2013 The mpI ortance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil Radhika Gupta Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious & Ethnic Diversity, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Gupta, Radhika (2012) "The mporI tance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 32: No. 1, Article 13. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol32/iss1/13 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADHIKA GUPTA MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGIOUS & ETHNIC DIVERSITY THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING LADAKHI: AFFECT AND ARTIFICE IN KARGIL Ladakh often tends to be associated predominantly with its Tibetan Buddhist inhabitants in the wider public imagination both in India and abroad. It comes as a surprise to many that half the population of this region is Muslim, the majority belonging to the Twelver Shi‘i sect and living in Kargil district. This article will discuss the importance of being Ladakhi for Kargili Shias through an ethnographic account of a journey I shared with a group of cultural activists from Leh to Kargil. -

The Baltistan Movement and the Power of Pop Ghazals

Jan Magnusson Lund University, Sweden The Baltistan Movement and the Power of Pop Ghazals This article investigates the role of locally produced pop ghazal music in the politics of the people of Baltistan, a community living in the western Hima- layas on both sides of the border between India and Pakistan and character- ized by its blend of Shi’ite and Tibetan culture and its vernacular Tibetan dialect. The pop ghazals conjure up an alternative narrative of local history and belonging that is situated in a Himalayan, rather than South Asian, con- text. Pop ghazals are emblematic for local resistance against the postcolonial nationalism of the Indian and Pakistani nation-states and are at the core of the Baltistan Movement, a western Himalayan social movement emerging in the past two decades. The analytical perspective is a continuation of Manuel’s (1993) work on the cassette culture of northern India that explores the politi- cal power of the pop ghazal further by drawing on Scott’s (1990) concept of hidden/public transcript and Smelser’s (1968) social strain model of the dynamics of social change. keywords: Baltistan—Himalaya—Tibet—Kargil—Skardu—ghazal— cassette culture—hidden/public transcript—social strain—social change Asian Ethnology Volume 70, Number 1 • 2011, 33–57 © Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture an pop music play a role in Himalayan contemporary social change? In the C Baltistan Movement of the western Himalayas, pop versions of the tradi- tional Arabic, Persian, or Urdu ghazal sung in the vernacular Tibetan dialect seem to have acquired a political power by innocuously expressing local political resis- tance against the nation-states of India and Pakistan. -

Introducing Another Script for Writing Balti

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3842 L2/10-231 2010-07-13 Title: Introducing Another Script for Writing Balti Author: Anshuman Pandey ([email protected]) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by UTC and WG2 Date: 2010-07-13 1 Introduction A script named ‘Balti’ was brought to the attention of UTC and WG2 by Rick McGowan in 1997 in “Unicode Technical Report #3” (N2042). It was allocated in the roadmap to the Supplementary Multilingual Plane, but has not yet been encoded. The present author recently learned about another script used for writing the Balti language, which differs entirely from the script identified in N2042. The information available about this second script is limited, but script charts and a manuscript are available. This document provides some background details on the script as well as a basic character repertoire with tentative names and properties. Research is ongoing and a preliminary proposal to encode the script in the Universal Character Set will be submitted once additional details have been gathered. 2 Background Balti [bft] (Tibetan sBal-ti; Urdu baltī) is Tibeto-Burman language that belongs to the Western Ti- ལ་ཏི་ फ betan sub-family, which also includes Ladakhi [lbj], Purik [prx], and Zangskari [zau]. It is spoken primarily in the Baltistan (Baltiyul) region of northern Pakistan and in neighboring Ladakh in India. There is no of- ficial script for Balti. The Tibetan script was introduced in the 8th century when the region was brought under Tibetan control.1 The Arabic script replaced the Tibetan in the 17th century as the influence of Islam grew in the region. -

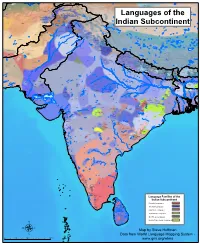

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

General Historical and Analytical / Writing Systems: Recent Script

9 Writing systems Edited by Elena Bashir 9,1. Introduction By Elena Bashir The relations between spoken language and the visual symbols (graphemes) used to represent it are complex. Orthographies can be thought of as situated on a con- tinuum from “deep” — systems in which there is not a one-to-one correspondence between the sounds of the language and its graphemes — to “shallow” — systems in which the relationship between sounds and graphemes is regular and trans- parent (see Roberts & Joyce 2012 for a recent discussion). In orthographies for Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages based on the Arabic script and writing system, the retention of historical spellings for words of Arabic or Persian origin increases the orthographic depth of these systems. Decisions on how to write a language always carry historical, cultural, and political meaning. Debates about orthography usually focus on such issues rather than on linguistic analysis; this can be seen in Pakistan, for example, in discussions regarding orthography for Kalasha, Wakhi, or Balti, and in Afghanistan regarding Wakhi or Pashai. Questions of orthography are intertwined with language ideology, language planning activities, and goals like literacy or standardization. Woolard 1998, Brandt 2014, and Sebba 2007 are valuable treatments of such issues. In Section 9.2, Stefan Baums discusses the historical development and general characteristics of the (non Perso-Arabic) writing systems used for South Asian languages, and his Section 9.3 deals with recent research on alphasyllabic writing systems, script-related literacy and language-learning studies, representation of South Asian languages in Unicode, and recent debates about the Indus Valley inscriptions. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Mandarin Chinese Evenki Oroqen Tuva China Buriat Russian Southern Altai Oroqen Mongolia Buriat Oroqen Russian Evenki Russian Evenki Mongolia Buriat Kalmyk-Oirat Oroqen Kazakh China Buriat Kazakh Evenki Daur Oroqen Tuva Nanai Khakas Evenki Tuva Tuva Nanai Languages of China Mongolia Buriat Tuva Manchu Tuva Daur Nanai Russian Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Halh Mongolian Manchu Salar Korean Ta tar Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Northern UzbekTuva Russian Ta tar Uyghur SalarNorthern Uzbek Ta tar Northern Uzbek Northern Uzbek RussianTa tar Korean Manchu Xibe Northern Uzbek Uyghur Xibe Uyghur Uyghur Peripheral Mongolian Manchu Dungan Dungan Dungan Dungan Peripheral Mongolian Dungan Kalmyk-Oirat Manchu Russian Manchu Manchu Kyrgyz Manchu Manchu Manchu Northern Uzbek Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Korean Kyrgyz Northern Uzbek West Yugur Peripheral Mongolian Ainu Sarikoli West Yugur Manchu Ainu Jinyu Chinese East Yugur Ainu Kyrgyz Ta jik i Sarikoli East Yugur Sarikoli Sarikoli Northern Uzbek Wakhi Wakhi Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Ainu Tu Wakhi Wakhi Khowar Tu Wakhi Uyghur Korean Khowar Domaaki Khowar Tu Bonan Bonan Salar Dongxiang Shina Chilisso Kohistani Shina Balti Ladakhi Japanese Northern Pashto Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Amdo Tibetan Northern Hindko Kashmiri Purik Choni Ladakhi Changthang Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Japanese Bhadrawahi Zangskari Kashmiri Baima Ladakhi Pangwali Mandarin Chinese Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Japanese Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Ladakhi Northern Qiang -

Ladakh Studies 22

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES 22 July 2008 ISSN 1356-3491 THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES Patrons: Tashi Rabgias and Kacho Sikander Khan President: John Bray, 1208 2-14-1; Furuishiba, Koto-ku; Tokyo, Japan [email protected] EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: Honorary Secretary: Dr. Monisha Ahmed Praneta, Flat 2, 23 B Juhu Tara Road, Mumbai 400 049 INDIA [email protected] Honorary Editor: Prof. Kim Gutschow Departments of Religion and Anthropology North Building #338 Williams College Williamstown, MA 01267 USA [email protected] Honorary Treasurer and Membership Secretary: Francesca Merritt, 254 West End Road; Ruislip, Mx; HA4 6DX United Kingdom ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Ravina Aggarwal (USA) Rev. E.S. Gergan (LSC) Maria Phylactou (UK) Monisha Ahmed (India) Kim Gutschow (USA) Mohd. Raza Abbasi (LSC) John Crook (UK) Clare Harris (UK) Janet Rizvi (India) Mohamed Deen Darokhan Mohd. Jaffar Akhoon (LSC) Abdul Ghani Sheikh (LSC) (LSC) Jamyang Gyaltsen (LSC) Harjit Singh (India) David Sonam Dawa (LSC) Erberto Lo Bue (Italy) Sonam Wangchuk (LSC) Philip Denwood (UK) Seb Mankelow (UK) Tashi Morup (LSC) Thierry Dodin (Germany) Gudrun Meier (Germany) Tashi Ldawa Tshangspa Kaneez Fatima (LSC) Gulzar Hussain Munshi (LSC) (LSC) Uwe Gielen (USA) Nawang Tsering (LSC) Thupstan Paldan (LSC) Mohd. Salim Mir (LSC) Nawang Tsering Shakspo (LSC) LADAKH SUBCOMMITTEE (LSC) OFFICERS: Dr. Nawang Tsering (Chairman), Principal, Gulzar Hussain Munshi (Hon.Treas., Kargil Central Institute of Buddhist Studies, Choglamsar Distt.) 147 Munshi Enclave, Lancore, Kargil 194103 Abdul Ghani Sheikh (Hon. Sec., Yasmin Hotel, Tashi Morup (Hon. Treas. Leh Distt) Room 9 Leh- Ladakh 194101) Hemis Compound, Leh-Ladakh 194101 For the last three decades, Ladakh (made up of Leh and Kargil districts) has been readily accessible for academic study. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Pashto, Southern Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Shughni Chinese, Mandarin Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Wakhi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Khowar Khowar Domaaki Khowar Kati Shina Farsi, Eastern Yidgha Munji Kati Kalasha Gujari Kati KatiPhalura Gujari Kalami Shina, Kohistani Gawar-BatiKamviri Kalami Dameli TorwaliKohistani, Indus Gujari Chilisso Pashayi, Northwest Prasuni Kamviri Balti Kati Ushojo Gowro Languages of the Gawar-Bati Waigali Savi Chilisso Ladakhi Ladakhi Bateri Pashayi, SouthwestAshkun Tregami Pashayi, Northeast Shina Purik Grangali Shina Brokskat ParyaPashayi, Southeast Aimaq Shumashti Hindko, Northern Hazaragi GujariKashmiri Pashto, Northern Purik Tirahi Ladakhi Changthang Kashmiri Gujari Indian Subcontinent Gujari Pahari-PotwariGujari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Hindko, Southern Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Ormuri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Dogri-Kangri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Pashto, Southern Ladakhi Pashto, Central Khams Pahari, Kullu Kinnauri, Bhoti KinnauriSunam Gahri Shumcho Panjabi, Western Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Kinnauri, Chitkuli Pahari, Mahasu Panjabi, Eastern Panang Jaunsari Garhwali Balochi, Western Pashto, Southern Khetrani Tehri Rawat Tibetan Hazaragi Waneci Rawat Brahui Saraiki DarmiyaByangsi Chaudangsi Tibetan Balochi, Western Chaudangsi Bagri Kumauni Humla Bhotia Rangkas Dehwari Mugu Kumauni Tichurong Dolpo Haryanvi Urdu Buksa Lopa Nepali Kaike Panchgaunle Balochi, Eastern Raute Tichurong Sholaga Baragaunle Raji Nar Phu Tharu, Rana Sonha Thakali Kham, GamaleKham, Sheshi -

Graduate School of International Development

Discussion Paper No.175 A Comparative Analysis of Classical Tibetan (CT) and Dzongkha (DZ) basic vocabulary Dorji Gyaltshen November 2009 Graduate School of International Development NAGOYA UNIVERSITY NAGOYA 464-8601, JAPAN 〒464-8601 名古屋市千種区不老町 名古屋大学大学院国際開発研究科 A Comparative Analysis of Classical Tibetan (CT) and Dzongkha (DZ) basic vocabulary Dorji Gyaltshen 1 Abstract The kingdom of Bhutan is home to as many as nineteen different spoken languages of the Tibeto-Burman language. Dzongkha, the national language, is traditionally spoken in eight of the twenty districts. Linguistically, a Tibetan dialect, however, has its vocabulary and prosodic features different from the CT. Dzongkha tends to preserve the old form of Tibetan at least orthographically. Many Dzongkha lexicons have its cognates in old Tibetan. While the subjoined CT ra-btags are substituted with subjoined ya-btags in Dzongkha, the ra-gbags to p/, / ph/ and b/ initials, in particular, have resulted orthographical change in Dzongkha. Spra (tra), monkey in CT, for example, is spya (pya) in Dzongkha and likewise brag (dag) ‘rock’ is byag. The fundamental difference is also due to contraction of the CT dissyllable nouns to monosyllables as in ka-ba (pillar) ka-w, lag-pa (hand) la-p and bu-mo ‘girl’, of such several final letters. Further, orthographical change from CT words is also due to the phonological shift from CT nasal to aspirate /ha/ in Dzongkha. This paper attempts to analyse CT and DZ basic lexical items, development of newly written DZ orthography based on written CT. Some phonological changes in Dzongkha have also been discussed. Introduction Bhutan is home to nineteen different spoken languages of the Tibeto-Burman language, except Nepali of the Indo- Aryan origin which is spoken along the southern border.