The Importance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compte Rendu De: Ladakhi Histories

Compte rendu de : Ladakhi Histories: Local and regional perspectives Pascale Dollfus To cite this version: Pascale Dollfus. Compte rendu de : Ladakhi Histories: Local and regional perspectives . 2006, pp.172- 177. halshs-01694592 HAL Id: halshs-01694592 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01694592 Submitted on 2 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 172 EBHR 29-30 Ladakhi Histories: Local and regional perspectives, edited by John Bray. Leiden: Brill (Tibetan Studies Library, 9). 2005. x + 406 pages, 36 maps, figures and plates, index. ISBN 90 04 14551 6. Reviewed by Pascale Dollfus, Paris. This volume illustrates the plurality of approaches to studying history and current research in the making. It compiles contributions – very different in length and in style – from researchers from a variety of disciplines: linguistics, tibetology, anthropology, history, art and archaeology. Their sources include linguistics, archaeological and artistical evidence; Tibetan chronicles, Persian biographies and European travel accounts; government records and private correspondence, land titles and trade receipts; oral tradition and reminiscence of survivors' recollections. The majority of the papers were first presented at the International Association of Ladakh Studies (IALS) conferences held in 1999, 2001 and 2003, and these have been supplemented by a few additional contributions. -

Impact of Climatic Change on Agro-Ecological Zones of the Suru-Zanskar Valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India

Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment Vol. 3(13), pp. 424-440, 12 November, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JENE ISSN 2006 - 9847©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Impact of climatic change on agro-ecological zones of the Suru-Zanskar valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India R. K. Raina and M. N. Koul* Department of Geography, University of Jammu, India. Accepted 29 September, 2011 An attempt was made to divide the Suru-Zanskar Valley of Ladakh division into agro-ecological zones in order to have an understanding of the cropping system that may be suitably adopted in such a high altitude region. For delineation of the Suru-Zanskar valley into agro-ecological zones bio-physical attributes of land such as elevation, climate, moisture adequacy index, soil texture, soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity have been taken into consideration. The agricultural productivity of the valley has been worked out according to Bhatia’s (1967) productivity method and moisture adequacy index has been estimated on the basis of Subrmmanyam’s (1963) model. The land use zone map has been superimposed on moisture adequacy index, soil texture and soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity zones to carve out different agro-ecological boundaries. The five agro-ecological zones were obtained. Key words: Agro-ecology, Suru-Zanskar, climatic water balance, moisture index. INTRODUCTION Mountain ecosystems of the world in general and India in degree of biodiversity in the mountains. particular face a grim reality of geopolitical, biophysical Inaccessibility, fragility, diversity, niche and human and socio economic marginality. -

Distribution of Bufotes Latastii (Boulenger, 1882), Endemic to the Western Himalaya

Alytes, 2018, 36 (1–4): 314–327. Distribution of Bufotes latastii (Boulenger, 1882), endemic to the Western Himalaya 1* 1 2,3 4 Spartak N. LITVINCHUK , Dmitriy V. SKORINOV , Glib O. MAZEPA & LeO J. BORKIN 1Institute Of Cytology, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Tikhoretsky pr. 4, St. Petersburg 194064, Russia. 2Department of Ecology and EvolutiOn, University of LauSanne, BiOphOre Building, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland. 3 Department Of EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy, EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy Centre (EBC), Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. 4ZoOlOgical Institute, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 1, St. PeterSburg 199034, Russia. * CorreSpOnding author <[email protected]>. The distribution of Bufotes latastii, a diploid green toad species, is analyzed based on field observations and literature data. 74 localities are known, although 7 ones should be confirmed. The range of B. latastii is confined to northern Pakistan, Kashmir Valley and western Ladakh in India. All records of “green toads” (“Bufo viridis”) beyond this region belong to other species, both to green toads of the genus Bufotes or to toads of the genus Duttaphrynus. B. latastii is endemic to the Western Himalaya. Its allopatric range lies between those of bisexual triploid green toads in the west and in the east. B. latastii was found at altitudes from 780 to 3200 m above sea level. Environmental niche modelling was applied to predict the potential distribution range of the species. Altitude was the variable with the highest percent contribution for the explanation of the species distribution (36 %). urn:lSid:zOobank.Org:pub:0C76EE11-5D11-4FAB-9FA9-918959833BA5 INTRODUCTION Bufotes latastii (fig. 1) iS a relatively cOmmOn green toad species which spreads in KaShmir Valley, Ladakh and adjacent regiOnS Of nOrthern India and PakiStan. -

Current Affairs October 2020

Current Affairs 2020 Current Affairs October 2020 International Day of Rural Women 2020 International Day of Rural Women is celebrated on 15 October. From agriculture to food security, nutrition, land and natural resource management, domestic care and work, rural women are at the forefront and are taking charge by being in the driver's seat. The International Day of Rural Women was created in 1995 by Civil society organizations at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing and was declared an official UN Day in 2007 by the UN General Assembly. From agriculture to food security, nutrition, land and natural resource management, domestic care and work, rural women are at the forefront. The theme for this International Day of Rural Women is “Building rural women’s resilience in the wake of COVID-19,” to create awareness of these women’s struggles, their needs, and their critical and key role in our society. Cabinet approved Special Package for UT of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh Union Cabinet has approved a Special Package worth Rs. 520 crore in the UTs of J&K and Ladakh for a period of five years till FY 2023-24 and ensure funding of DeendayalAntyodaya Yojana - National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM) in the UTs of Jammu and Kashmir & Ladakh on a demand driven basis without linking allocation with poverty ratio during this extended period. This will ensure sufficient funds under the Mission, as per need to the UTs and is also in line with Government of India's aim to universalize all centrally sponsored beneficiary-oriented schemes in the UTs of J&K and Ladakh in a time bound manner. -

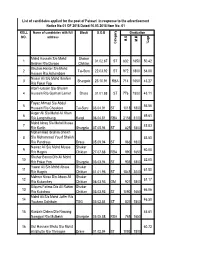

1 Mohd Hussain S/O Mohd Ibrahim R/O Dargoo Shakar Chiktan 01.02

List of candidates applied for the post of Patwari in response to the advertisement Notice No:01 OF 2018 Dated:10.03.2018 Item No: 01 ROLL Name of candidates with full Block D.O.B Graduation NO. address M.O M.M %age Category Category Mohd Hussain S/o Mohd Shakar 1 01.02.87 ST 832 1650 50.42 Ibrahim R/o Dargoo Chiktan Ghulam Haider S/o Mohd 2 Tai-Suru 22.03.92 ST 972 1800 54.00 Hassan R/o Achambore Nissar Ali S/o Mohd Ibrahim 3 Shargole 23.10.91 RBA 714 1650 43.27 R/o Fokar Foo Altaf Hussain S/o Ghulam 4 Hussain R/o Goshan Lamar Drass 01.01.88 ST 776 1800 43.11 Fayaz Ahmad S/o Abdul 5 56.56 Hussain R/o Choskore Tai-Suru 03.04.91 ST 1018 1800 Asger Ali S/o Mohd Ali Khan 6 69.61 R/o Longmithang Kargil 06.04.81 RBA 2158 3100 Mohd Ishaq S/o Mohd Mussa 7 45.83 R/o Karith Shargole 07.05.94 ST 825 1800 Mohammad Ibrahim Sheikh 8 S/o Mohammad Yousf Sheikh 53.50 R/o Pandrass Drass 05.09.94 ST 963 1800 Nawaz Ali S/o Mohd Mussa Shakar 9 60.00 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 27.07.88 RBA 990 1650 Shahar Banoo D/o Ali Mohd 10 52.00 R/o Fokar Foo Shargole 03.03.94 ST 936 1800 Yawar Ali S/o Mohd Abass Shakar 11 61.50 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 01.01.96 ST 1845 3000 Mehrun Nissa D/o Abass Ali Shakar 12 51.17 R/o Kukarchey Chiktan 06.03.93 OM 921 1800 Bilques Fatima D/o Ali Rahim Shakar 13 66.06 R/o Kukshow Chiktan 03.03.93 ST 1090 1650 Mohd Ali S/o Mohd Jaffer R/o 14 46.50 Youkma Saliskote TSG 03.02.84 ST 837 1800 15 Kunzais Dolma D/o Nawang 46.61 Namgyal R/o Mulbekh Shargole 05.05.88 RBA 769 1650 16 Gul Hasnain Bhuto S/o Mohd 60.72 Ali Bhutto R/o Throngos Drass 01.02.94 ST -

Reru Valley Expedition Proposal 2011

RERU VALLEY EXPEDITION PROPOSAL 2011 FOREWORD The destination of this expedition is to the Reru valley in the Zanskar range. This range is located in the north East of India in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, between the Great Himalayan range and the Ladakh range. Until 2009 there had been no climbing expeditions to the valley, and there are a large number of unclimbed summits between 5700m and 6200m in this area: only two of the 36 identified peaks have seen ascents. Our expedition aims to take a large group of 7 members that will use a single base camp but split into two teams that will attempt different types of objective. One team will focus on technical rock climbing ascents, whilst the other team will focus on alpine style mixed snow and rock ascents of unclimbed peaks with a target elevation of around 6000m. CONTENTS 1. Expedition Aims & Objectives ............................................................................................................................. 3 2. Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Itinerary ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 4. Expedition Team ............................................................................................................................................... 13 5. Logistics ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Historical Places

Where to Next? Explore Jammu Kashmir And Ladakh By :- Vastav Sharma&Nikhil Padha (co-editors) Magazine Description Category : Travel Language: English Frequency: Twice in a Year Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh Unlimited is the perfect potrait of the most beautiful place of the world Jammu, Kashmir&Ladakh. It is for Travelers, Tourism Entrepreneurs, Proffessionals as well as those who dream to travel Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh and have mid full of doubts. This is a new kind of travel publication which trying to promoting the J&K as well as Ladakh tourism industry and remove the fake potrait from the minds of people which made by media for Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh. Jammu Kashmir and ladakh Unlimited is a masterpiece, Which is the hardwork of leading Travel writters, Travel Photographer and the team. This magazine has covered almost every tourist and pilgrimage sites of Jammu Kashmir & Ladakh ( their stories, history and facts.) Note:- This Magazine is only for knowledge based and fact based magazine which work as a tourist guide. For any kind of credits which we didn’t mentioned can claim for credits through the editors and we will provide credits with description of the relevent material in our next magazine and edit this one too if possible on our behalf. Reviews “Kashmir is a palce where not even words, even your emotions fail to describe its scenic beauty. (Name of Magazine) is a brilliant guide for travellers and explore to know more about the crown of India.” Moohammed Hatim Sadriwala(Poet, Storyteller, Youtuber) “A great magazine with a lot of information, facts and ideas to do at these beautiful places.” Izdihar Jamil(Bestselling Author Ted Speaker) “It is lovely and I wish you the very best for the initiative” Pritika Kumar(Advocate, Author) “Reading this magazine is a peace in itself. -

Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %Age 1 1898155 MOHD BAQIR MOHAMMED ALI FAROONA P-O SALISKOTE

Selection List of candidates who have applied for admission to B. Ed Programme (Kargil Chapter) offered through Directorate of Admisssions, University of Kashmir session-2018 Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %age OM 1 1898155 MOHD BAQIR MOHAMMED ALI FAROONA P-O SALISKOTE, KARGIL KARGIL ST 9 7.09 78.78 2 1898735 SHAHAR BANOO MOHAMMAD BAQIR BAROO KARGIL KARGIL ST 10 7.87 78.70 3 1895262 FARIDA BANOO MOHD HUSSAIN SHAKAR KARGIL ST 2400 1800 75.00 VILLAGE PASHKUM DISTRICT KARGIL, 4 1897102 HABIBULLAH MOHD BAQIR LADAKH. KARGIL ST 3000 2240 74.67 5 1894751 ANAYAT ALI MOHD SOLEH STICKCHEY CHOSKORE KARGIL ST 2400 1776 74.00 6 1898483 STANZIN SALTON TASHI SONAM R/O MULBEK TEHSIL SHARGOLE KARGIL ST 3000 2177 72.57 7 1892415 IZHAR HUSSAIN NIYAZ ALI TITICHUMIK BAROO POST OFFICE BAROO KARGIL ST 3600 2590 71.94 8 1897301 MOHD HASSAN HADIRE MOHD IBRAHIM HARDASS GRONJUK THANG KARGIL KARGIL ST 3100 2202 71.03 9 1896791 MOHD HUSSAIN GHULAM MOHD ACHAMBORE TAISURU KARGIL KARGIL ST 4000 2835 70.88 10 1898160 MOHD HUSSAIN MOHD TOHA KHANGRAL,CHIKTAN,KARGIL KARGIL ST 3400 2394 70.41 11 1898257 MARZIA BANOO MOHD ALI R/O SAMRAH CHIKTAN KARGIL KARGIL ST 10 7 70.00 12 1893813 ZAIBA BANOO KACHO TURAB SHAH YABGO GOMA KARGIL KARGIL ST 2100 1466 69.81 13 1894898 MEHMOOD MOHD ALI LANKERCHEY KARGIL ST 4000 2784 69.60 14 1894959 SAJAD HUSSAIN MOHD HASSAN ACHAMBORE TAISURU KARGIL ST 3000 2071 69.03 15 1897813 IMRAN KHAN AHMAD KHAN CHOWKIAL DRASS KARGIL RBA 4650 3202 68.86 16 1897210 ARCHO HAKIMA SYED ALI SALISKOTE TSG KARGIL ST 500 340 68.00 17 -

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 “STATISTICAL HANDBOOK” DISTRICT KARGIL UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 RELEASED BY: DISTRICT STATISTICAL & EVALUATION OFFICE KARGIL D.C OFFICE COMPLEX BAROO KARGIL J&K. TELE/FAX: 01985-233973 E-MAIL: [email protected] Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH, Chairman/ Chief Executive Councilor, LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985 233827, 233856 Message It gives me immense pleasure to know that District Statistics & Evaluation Agency Kargil is coming up with the latest issue of its ideal publication “Statistical Handbook 2018-19”. The publication is of paramount importance as it contains valuable statistical profile of different sectors of the district. I hope this Hand book will be useful to Administrators, Research Scholars, Statisticians and Socio-Economic planners who are in need of different statistics relating to Kargil District. I appreciate the efforts put in by the District Statistics & Evaluation Officer and the associated team of officers and officials in bringing out this excellent broad based publication which is getting a claim from different quarters and user agencies. Sd/= (Feroz Ahmed Khan ) Chairman/Chief Executive Councilor LAHDC, Kargil Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH District Magistrate, (Deputy Commissioner/CEO) LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985-232216, Tele Fax: 232644 Message I am glad to know that the district Statistics and Evaluation Office Kargil is releasing its latest annual publication “Statistical Handbook” for the year 2018- 19. The present publication contains statistics related to infrastructure as well as Socio Economic development of Kargil District. -

Kargil Operation 1999

KARGIL OPERATION 1999 The Kargil War, also known as the Kargil conflict was an armed conflict between India and Pakistan that took place between May and July 1999 in the Kargil district of Kashmir and elsewhere along the Line of Control (LOC). In India, the conflict is also referred to as Operation Vijay which was the name of the Indian operation to clear the Kargil sector.The war is the most recent example of high-altitude warfare in mountainous terrain, and as such posed significant logistical problems for the combating sides.The cause of the war was the infiltration of Pakistani soldiers disguised as Kashmiri militants into positions on the Indian side of the LOC which serves as the border between the two states. During the initial stages of the war, Pakistan blamed the fighting entirely on independent Kashmiri insurgents, but documents left behind by casualties and later statements by Pakistan's Prime Minister and Chief of Army Staff showed involvement of Pakistani paramilitary forces led by General Ashraf Rashid. The Indian Army, later supported by the Indian Air Force, recaptured a majority of the positions on the Indian side of the LOC infiltrated by the Pakistani troops and militants. Facing international diplomatic opposition, the Pakistani forces withdrew from the remaining Indian positions along the LOC. There were three major phases to the Kargil War. First, Pakistan infiltrated forces into the Indian-controlled section of Kashmir and occupied strategic locations enabling it to bring NH1 within range of its artillery fire. The next stage consisted of India discovering the infiltration and mobilising forces to respond to it. -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern