Fakir Mohan Senapati: the Trend Setter of Everyday Speaking Language of Common Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue1 Ser. II || Jan, 2020 || PP 01-04 The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature Dr. Ajay Kumar Panda Sr. Lecturer in Odia Upendranath College, Soro, Balasore, Odisha ABSTRACT : Feminism, in literature as well as otherwise, began as an expression of dissatisfaction regarding the attitude of the society towards the identity and rights of women. However, slowly, it evolved to empower women to make her financially, socially and psychologically independent. In the field of literature, it evolved to finally enable the female writers to be free from the influence of male writers as well as the social norms that suggested different standards for male and female KEYWORDS – Feminism, identity and rights of women, empower women, free from the influence of male writers ,Sita, Draupadi,Balaram Das, Vaishanbism, Panchasakha, Kuntala Kumari, Rama Devi, Sarala Devi, Nandini Satapathy, Prativa Ray,Pratiova Satapathy, Sarojini Sahu.Ysohodhara Mishra ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ --------------- Date of Submission: 18-01-2020 Date of Acceptance: 06-02-2020 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION: Feminism in Indian literature, as can be most commonly conceived is a much sublime and over-the-top concept, -

Four Major Modern Oriya Novelists

Orissa Review * November - 2008 Four Major Modern Oriya Novelists Jitendra Narayan Patnaik While the first major event in the hundred-and- Panigrahi also wrote five novels, four of them twenty-year old history of the Oriya novel is the having been published in the nineteen-thirties and publication of Fakir Mohan Senapati's Cha Mana nineteen-forties. His first novel, Matira Manisha, Atha Guntha in 1897, its full potential as a published in 1931, is considered a modern classic legitimate literary form was realized during and in Oriya language. Its film version, directed by after the nineteen-thirties when Gandhian and Mrinal Sen, was a great success and won a Marxist ideologies as well as the politics of number of national awards. The plot revolves resistance against colonial power and a pervasive round the family of Shama Pradhan, a rural farmer sense of social reform in the wake of exposure to and his two sons, Baraju and Chakadi. At the modern educational system led to a renewed time of his death, Shama Pradhan entrusts Baraju vision of social and historical forces that found with the responsibility of looking after his younger felicity of expression in the new fictional form of son Chakadi and entreats him to prevent partition the prose narrative. The four novelists discussed of land and the house between the two brothers. in this paper began writing in the nineteen-thirties Baraju is a peace-loving person who commands and nineteen-forties and while three of them--- respect from the villagers for his idealistic way of Kanhu Charan Mohanty, Gopinath Mohanty and life. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXX NO. 8 MARCH - 2014 PRADEEP KUMAR JENA, I.A.S. Principal Secretary PRAMOD KUMAR DAS, O.A.S.(SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Sri Krsna - Jagannath Consciousness : Vyasa - Jayadeva - Sarala Dasa Dr. Satyabrata Das ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 Classical Language : Odia Subrat Kumar Prusty ... 4 Language and Language Policy in India Prof. Surya Narayan Misra ... 14 Rise of the Odia Novel : 1897-1930 Jitendra Narayan Patnaik ... 18 Gangadhar Literature : A Bird’s Eye View Jagabandhu Panda ... 23 Medieval Odia Literature and Bhanja Dynasty Dr. Sarat Chandra Rath ... 25 The Evolution of Odia Language : An Introspection Dr. Jyotirmati Samantaray ... 29 Biju - The Greatest Odia in Living Memory Rajkishore Mishra ... 31 Binode Kanungo (1912-1990) - A Versatile Genius ... 34 Role of Maharaja Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo in the Odia Language Movement Harapriya Das Swain ... 38 Odissi Vocal : A Unique Classical School Kirtan Narayan Parhi .. -

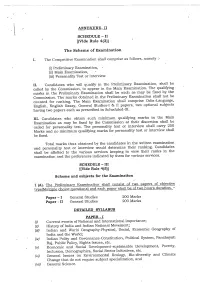

Ocs-2015-Syllabus-F0db7a3a.Pdf

Syllabi for the Odisha Civil Services (Main) Examination (Subject-wise) SYLLABUS FOR ODISHA CIVIL SERVICES (MAIN) EXAMINATION ODIA LANGUAGE The aim of the paper is to test the candidate’s ability to understand serious discursive prose and express his ideas clearly and correctly in Odia language. The pattern of questions would broadly be as follows:- Comprehension of a given passage .. 30 Marks Precis writing with a passage of around 1000 words .. 40 Marks Translation from English to Odia .. 30 Marks Grammar, usage and vocabulary .. 80 Marks Short Essay of around 1000 words .. 100 Marks Expansion of an idea .. 20 Marks Total .. 300 Marks ENGLISH The aim of the paper is to test the candidate’s ability to understand serious discursive prose and express his ideas clearly and correctly in English language. The pattern of questions would broadly be as follows :- Comprehension of a given passage .. 30 Marks Precis writing with a passage of around 1000 words .. 40 Marks Translation from Odia to English .. 30 Marks Grammar, usage and vocabulary .. 80 Marks Short Essay of around 1000 words .. 100 Marks Expansion of an idea .. 20 Marks Total .. 300 Marks ENGLISH ESSAY GENERAL INSTRUCTION Candidates will be required to write an Essay on a specific topic. The choice of subjects will be given. They will be expected to keep closely to the subject of the essay to arrange their ideas in orderly fashion and to write concisely. Credit will be given for effective and exact expression. GENERAL STUDIES The nature and standard of questions in this paper will be such that a well educated person will be able to answer them without any specialized study. -

Odia Identity, Language and Regionalism: a Historical Perspective

IAR Journal of Humanities and Social Science ISSN Print : 2708-6259 | ISSN Online : 2708-6267 Frequency: Bi-Monthly Language: Multilingual Origin: KENYA Website : https://www.iarconsortium.org/journal-info/IARJHSS Review Article Odia Identity, Language and Regionalism: A Historical Perspective Article History Abstract: The Odisha had a rich heritage in sphere of culture, religion, politics, and economy. They could maintain the same till they came contact with outsiders. However the Received: 18.12.2020 decay in all aspects started during the British Rule. The main aim of the paper is to Revision: 03.01.2021 understand the historical development of Odia language particularly in the colonial period Accepted: 29.01.2021 which in the later time formed the separate state basing on language. The Odia who could realize at the beginning of the 20th century proved their mettle in forming the Published: 15.02.2021 Odisha province in 1936 and amalgamating Garhjat States in 1948 and 1950. Equally there Author Details are huge literature in defending the Odia language and culture by Odia and non-Odia writers Laxmipriya Palai and activists of the century. Similarly, from the beginning of the 20th century and with the growth of Odia nationalism, the Odias had to struggle for formation of Odisha with the Authors Affiliations amalgamation of Odia speaking tracts from other province and play active role in freedom P.G. Dept. of History, Berhampur University, movement. Berhampur-760007, Odisha, India Keywords: Odia, language, identity, regionalism, amalgamation, movement, culture. Corresponding Author* Laxmipriya Palai How to Cite the Article: INTRODUCTION Laxmipriya Palai (2021); Odia Identity, Language By now, we have enough literature on how there was a systematic and Regionalism: A Historical Perspective . -

Paper 18 History of Odisha

DDCE/History (M.A)/SLM/Paper-18 HISTORY OF ODISHA (FROM 1803 TO 1948 A.D.) By Dr. Manas Kumar Das CONTENT HISTORY OF ODISHA (From 1803 TO 1948 A.D.) Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No UNIT- I. a. British Occupation of Odisha. b. British Administration of Odisha: Land Revenue Settlements, administration of Justice. c. Economic Development- Agriculture and Industry, Trade and Commerce. UNIT.II. a. Resistance Movements in the 19th century- Khurda rising of 1804-05, Paik rebellion of 1817. b. Odisha during the revolt of 1857- role of Surendra Sai c. Tribal uprising- Ghumsar Rising under Dara Bisoi, Khond Rising under Chakra Bisoi, Bhuyan Rising Under Ratna Naik and Dharani Dhar Naik. UNIT – III. a. Growth of Modern Education, Growth of Press and Journalism. b. Natural Calamities in Odisha, Famine of 1866- its causes and effect. c. Social and Cultural changes in the 19th Century Odisha. d. Mahima Dharma. UNIT – IV. a. Oriya Movement: Growth of Socio-Political Associations, Growth of Public Associations in the 19th Century, Role of Utkal Sammilini (1903-1920) b. Nationalist Movement in Odisha: Non-Cooperation and Civil Disobedience Movements in Odisha. c. Creation of Separate province, Non-Congress and Congress Ministries( 1937-1947). d. Quit India Movement. e. British relation with Princely States of Odisha and Prajamandal Movement and Merger of the States. UNIT-1 Chapter-I British Occupation of Odisha Structure 1.1.0. Objectives 1.1.1. Introduction 1.1.2. British occupation of Odisha 1.1.2.1. Weakness of the Maratha rulers 1.1.2.2. Oppression of the land lords 1.1.2.3. -

Odisha Review

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXIX NO. 6 JANUARY - 2013 PRADEEP KUMAR JENA, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum- Secretary DEBENDRA PRASAD DAS, O.A.S.(SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Bikram Maharana Production Assistance Debasis Pattnaik Sadhana Mishra Manas R. Nayak Cover Design & Illustration Hemanta Kumar Sahoo D.T.P. & Design Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty Photo The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. E-mail : [email protected] Five Rupees / Copy [email protected] Visit : http://orissa.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Buddha - Jagannath in the Evolution Process Dr. Harihar Kanungo ... 1 Good Governance ... 5 Constitutional Democracy, Judiciary and Social Justice in India Dr. Surya Narayan Misra ... 16 Our Republican Moorings Lagnajit Ray ... 21 Reminiscing with the Legend : An Interview with Smt. Annapurna Moharana Dr. Pragyan Das ... 24 Past Significance and Present Meaning in Fakir Mohan Senapati’s Rebati Dr. Shruti Das ... 30 The Novels of Pratibha Ray Prafulla Kumar Mohanty ... 37 Kantakabi: The Poet of Odisha State Song Asit Mohanty ... 42 Tr.: Bibhu Chandra Mishra Bikram Maharana Swami Vivekananda : The Prophet of Human Emancipation Souribandhu Kar ... 47 Netaji : A Profile Jagannath Mohanty ... 51 Samba Dasami in Odishan Culture Dr. -

Classical2.Pdf

Contents Chapter-I 19 Introduction Odia & Odisha 1.1 Udra to Odisha 1.2 Literary and Epigraphical Sources 1.3 Visitors’ Accounts Chapter-II 29 Odia Language and Script 2.1 Odia Language 2.2 Odia Script CONTENTS a. Odia Script in the Inscription b. Odia Script in Palm leaf manuscripts Chapter-III 41 Pre-History of Odisha 3.1 Stone Age Culture 3.2 Copper – Bronze Age 3.3. Iron / Megalithic Age 3.4 Pre-historic sites Chapter-IV History of Odisha 4.1 Kalinga Janapada 4.2 Nanda Rule 4.3 Kalinga War and Mauryan Empire 4.4 Mahameghavana Emperor 4.5 Satavahana & Murundas 4.6 Naga dynasties 4.7 The Guptas 4.8 The Matharas 4.9 The Eastern Gangas 4.10 The Sailodbhavas 4.11 The Sailodbhavas & Srivijaya kingdom 4.12 The Bhaumakaras 4.13 The Somavamsis 4.14 The Imperial Gangas 4.15 The Suryavamsi 4.16 Afghan rule .................................................................................................................................... 4.17 Mughal Rule 4.18 Maratha Rule 4.19 British Rule 4.20 Freedom movement 4.21 Lessons of History Chapter-V Maritime history of Odisha 5.1 Crafts and Trade 5.2 Boita 5.3 Bali Jatra 5.4 Ancient Ports of Odisha a. Tamralipti b. Palur/ Dantapura c. Che-li-ta-lo d. Golbai Sasan e. Manikpatna and Khalakatapatna f. Dosareene g. Pithunda od Pihunda 5.5 Literary Sources 5.6 Inscriptional and Epigraphic records 5.7 Archaeological Evidence CONTENTS 5.8 Numismatic Evidence 5.9 Art and Sculptural Evidence 5.10 Overseas Routes 5.11 Overseas contacts & Colonization a. Burma b. Java c. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXIV NO.9 APRIL - 2018 HEMANT SHARMA, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary LAXMIDHAR MOHANTY, O.A.S Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Kishor Kumar Sinha Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty Niranjan Baral The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Rs.5/- Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Special Development Council ... ... 1 The Contributions of Harihar Mardaraj Dr. Dasarathi Bhuiyan ... 4 for the Formation of New Odisha Dr. Prafulla Kumar Maharana Depicting Upanishads as the Secret of Life and the Universe Santosh Kumar Nayak ... 11 Dalit Literature in Odia Prof. Udayanath Sahoo ... 21 Integration of the Princely States and Dr. Harekrushna Mahtab Dr. Bhagabat Tripathy ... 28 British Relations with the Princely States of Odisha (1905-1947) Sunita Panigrahy ... 33 The First Ministry of Biju Patnaik : An Analysis Sudarsan Pradhan ... 39 Kalinga and China : A Study in Ancient Relations Dr. Benudhar Patra ... 42 Reinforcing Power to People : Revamping the Frontiers of Panchayati Raj Dr. Girish P. -

Sovenir -2008

CONTENTS 1. Message from Governor of Gujarat 3 2. Message from Chief Minister of Gujarat 5 3. Message from Minister, Revenue & Disaster Management, Orissa 7 4. Message from Minister of Tourism, Orissa 9 5. Message from Commissioner of Income Tax-1, Baroda 11 6. Message from Chief Commissioner Excise & Customs 12 7. From President’s Desk 13 8. News of Divya Bhaskar 14 9. Secretary Forward 15 10. Media Coverage By Sandesh 16 11. Ganesha Symbolism 20 12. A Guide to Orissa State Museum 21 13. Useful Info, on Cancer 24 14. Give Thanks 25 15. “As is” Questions “Shoud be” Your Key to Success 26 16. The Egoless Mind 28 17. The Festive Spirit 29 18 Konark 30 19. Prayer Timetable 31 20. Tour Orissa 32 21. Solar Cooker 34 22. Sattellite 35 23. A to Z Life 41 24. My Brother 41 25. Temples 42 26. Maa Sarala 45 27. Saint Poet Bhima Bhoi 47 28. Impact of Indian Culture on Modern Life 50 29. Sense of Morality 51 30. Specialities of Ayurveda for Rejuvenation and Cure 53 31. Jokes 54 32. Open your Eyes 56 33 Winner of Talent Search Competition 56 34. jbÞþHÜ AÒc HL 61 35. LaÞ[Ð HL dÊNê kóþ]¯Æeþ 61 36. ]ÞÒ_ LíÞ_ÞLç Òeþ 63 37. JXÏÞA LaÞ[ÐÒeþ `mîþÑ jÕ²ôÆ[Þ 65 38. @có[ jõ½¤Ð 69 39. aÞQÐeþ Leþ jÊSÒ_ 71 40. SÑa `eþc jcjÔÐ 71 41. NÊeÊþ ckÞþcÐjèÐcÑ ckÞþcÐ ^cà J j_ÔÐj `xÐeþ `õ[Þº¤Ð[Ð 72 40. Life Members 77 41. Members List 78 UTKALIKA ORISSA SEVA TRUST- BARODA 102, Gajanand Chamber, Nr.