The Book of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astrology, Astronomy and Spiritualism in 'Siddhanta Darpana'

Odisha Review January - 2012 Astrology, Astronomy and Spiritualism in µSiddhanta Darpana¶: A Comparison with Similar Thoughts Dr. K.C. Sarangi Jyotisham api tatjyotih «««« Jnanam jneyam jnanagamyam ««« (Gita, Chapter 13, Verse-18) The creator of µSiddhanta Darpana¶ was indeed one among millions. He worked and struggled in the solitude to µhear the unheard and glimpse the invisible¶. µSiddhanta Darpana¶ is an immortal this great book. One may, therefore, benefit creation of the famous Odia astrologer Samanta the knowledge of all astrological literature by Chandrasekhar. Astrology emanates from the reading this one great book on astrology. Vedic thoughts. It is immensely useful for the Secondly, the writer, Late Samanta society. Aruna Kumar Upadhyaya, in his Chandrasekhara, wherever, had not explained translation of µSiddhanta Darpana¶ in Devnagari the astrological theories of the past, he had, script writes: at least, given indication how to approach the same. Last but not least, Chandrasekhara had µUdwesya Jyotisa¶ is known as the eyes of the made correction in the movement of the Moon. Vedas. Setting it apart, it is difficult to know In its correctness, it is equal to the modern the time of ancient literature and scriptures. astronomy. (Ibid, Preface-ii). Without knowing time of the scriptures, any discussion on the Sashtras may not be proper As a subject, the present astrology in and hence may not be understood in the proper India is taken into account from the period of context. (Preface i) Aryabhatta. However, there are rare astrological master-pieces like, µJyotisha Bhaskar¶, written by Upadhyaya further clarifies with specific the Divine teacher Brihaspati, which shines like reference to µSiddhanta Darpana¶: the Sun in the sphere of astrological sciences. -

Global Journal of Human Social Science the Engagement Patters (Such As Listening)

OnlineISSN:2249-460X PrintISSN:0975-587X DOI:10.17406/GJHSS AnalysisofIslamicSermon PortrayalofRohingyaWomen NabakalebaraofLordJagannath TheRe-EmbodimentoftheDivine VOLUME20ISSUE7VERSION1.0 Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Volume 2 0 I ssue 7 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. *OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Social Sciences. 2020. Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Open Scientific Standards $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 7KLVLVDVSHFLDOLVVXHSXEOLVKHGLQYHUVLRQ Publisher’s Headquarters office RI³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 6FLHQFHV´%\*OREDO-RXUQDOV,QF Global Journals ® Headquarters $OODUWLFOHVDUHRSHQDFFHVVDUWLFOHVGLVWULEXWHG XQGHU³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 945th Concord Streets, 6FLHQFHV´ Framingham Massachusetts Pin: 01701, 5HDGLQJ/LFHQVHZKLFKSHUPLWVUHVWULFWHGXVH United States of America (QWLUHFRQWHQWVDUHFRS\ULJKWE\RI³*OREDO -RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO6FLHQFHV´XQOHVV USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 RWKHUZLVHQRWHGRQVSHFLILFDUWLFOHV USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 1RSDUWRIWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQPD\EHUHSURGXFHG Offset Typesetting RUWUDQVPLWWHGLQDQ\IRUPRUE\DQ\PHDQV HOHFWURQLFRUPHFKDQLFDOLQFOXGLQJ SKRWRFRS\UHFRUGLQJRUDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQ Global Journals Incorporated VWRUDJHDQGUHWULHYDOV\VWHPZLWKRXWZULWWHQ 2nd, Lansdowne, Lansdowne Rd., Croydon-Surrey, SHUPLVVLRQ Pin: CR9 2ER, United Kingdom 7KHRSLQLRQVDQGVWDWHPHQWVPDGHLQWKLV ERRNDUHWKRVHRIWKHDXWKRUVFRQFHUQHG 8OWUDFXOWXUHKDVQRWYHULILHGDQGQHLWKHU -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue1 Ser. II || Jan, 2020 || PP 01-04 The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature Dr. Ajay Kumar Panda Sr. Lecturer in Odia Upendranath College, Soro, Balasore, Odisha ABSTRACT : Feminism, in literature as well as otherwise, began as an expression of dissatisfaction regarding the attitude of the society towards the identity and rights of women. However, slowly, it evolved to empower women to make her financially, socially and psychologically independent. In the field of literature, it evolved to finally enable the female writers to be free from the influence of male writers as well as the social norms that suggested different standards for male and female KEYWORDS – Feminism, identity and rights of women, empower women, free from the influence of male writers ,Sita, Draupadi,Balaram Das, Vaishanbism, Panchasakha, Kuntala Kumari, Rama Devi, Sarala Devi, Nandini Satapathy, Prativa Ray,Pratiova Satapathy, Sarojini Sahu.Ysohodhara Mishra ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ --------------- Date of Submission: 18-01-2020 Date of Acceptance: 06-02-2020 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION: Feminism in Indian literature, as can be most commonly conceived is a much sublime and over-the-top concept, -

Dr. Milind Barhate (Principal) C.P

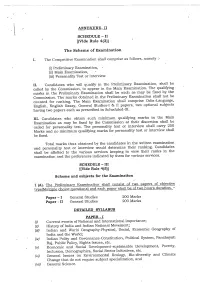

1 RE-ACCREDITATION REPORT (RAR – 2nd Cycle) (2010-11 to 2014-15) Submitted to: NATIONAL ASSESSMENT & ACCREDITATION COUNCIL BANGALORE - 560072 (NAAC) Western Region Submitted by: Dr. Milind Barhate (Principal) C.P. & Berar Education Society's C.P.& Berar College COLLEGE (Affiliated to Rashtrasant Tukdoji Maharaj Nagpur University) Nagpur (MS) Website: www.cpberar.co.in Email:[email protected] 2 College Building 3 Contents Page No Cover Page 1 College Building Photo 3 Contents 4 Preface 6 Principal‘s Message 7 IQAC 8 Criterion Wise Committees 8 Executive Summary 9 Re-Accreditation Report Profile of the Institution 14-24 Criteria-wise Analytical Report 1 Criterion I : Curricular Aspects 24-38 2 Criterion II : Teaching Learning and Evaluation 38-67 3 Criterion III : Research Consultancy and Extension 67-100 4 Criterion IV : Infrastructure and Learning Resources 101-118 5 Criterion V : Student Support and Progression 118-133 6 Criterion VI : Governance, Leadership and Management 133-151 7 Criterion VII : Innovations and Best Practices 151-166 Evaluative Reports From the Departments 1 Commerce 167-180 4 2 Marathi 180-203 3 English 203-214 4 Sanskrit 214-229 5 Economics 229-238 6 Political Science 238-245 7 Sociology 245-252 8 Psychology 252-262 9 Home Economics 262-269 10 History 269- 274 11 Physical Education 275-280 Post Accreditation Initiatives 280 Declaration by the Head of the Institution 281 Certificate of Compliance 282 Annexure 283 Approval to start college 283 Permanent Affiliation 284 Continuation of Affiliation 285-286 UGC 2 (f) 287 UGC Development Grant Letter XII Plan 288 Audit Report of Last Four Years 289-319 UGC Grant XI Plan – Utilization Certificate 320-326 Teaching Master Plan 327-331 Non Teaching Master Plan 332-336 5 Preface C.P.& Berar E.S. -

Four Major Modern Oriya Novelists

Orissa Review * November - 2008 Four Major Modern Oriya Novelists Jitendra Narayan Patnaik While the first major event in the hundred-and- Panigrahi also wrote five novels, four of them twenty-year old history of the Oriya novel is the having been published in the nineteen-thirties and publication of Fakir Mohan Senapati's Cha Mana nineteen-forties. His first novel, Matira Manisha, Atha Guntha in 1897, its full potential as a published in 1931, is considered a modern classic legitimate literary form was realized during and in Oriya language. Its film version, directed by after the nineteen-thirties when Gandhian and Mrinal Sen, was a great success and won a Marxist ideologies as well as the politics of number of national awards. The plot revolves resistance against colonial power and a pervasive round the family of Shama Pradhan, a rural farmer sense of social reform in the wake of exposure to and his two sons, Baraju and Chakadi. At the modern educational system led to a renewed time of his death, Shama Pradhan entrusts Baraju vision of social and historical forces that found with the responsibility of looking after his younger felicity of expression in the new fictional form of son Chakadi and entreats him to prevent partition the prose narrative. The four novelists discussed of land and the house between the two brothers. in this paper began writing in the nineteen-thirties Baraju is a peace-loving person who commands and nineteen-forties and while three of them--- respect from the villagers for his idealistic way of Kanhu Charan Mohanty, Gopinath Mohanty and life. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

Dr. Itirani Samanta Entrepreneur, Creative Writer, Journalist, Editor (Premier Monthly Family Magazine of the State), Publisher, Director (Kadambini Media Pvt

Dr. Itirani Samanta Entrepreneur, Creative Writer, Journalist, Editor (premier monthly family magazine of the state), Publisher, Director (Kadambini Media Pvt. Ltd.), National Award Winning Film Producer, Reputed Television Producer, Interviewer and Social Activist. 1 Dr. Itirani Samanta A women entrepreneur who is a Creative Writer, Journalist, Editor, Publisher, Director (Kadambini Media), National Award Winning Film Producer, Reputed Television Producer, Interviewer and Social Activist. Nationality : Indian Village : Kalarabank Dist : Cuttack State : Odisha PIN : 754132 Education : • Electronics & Telecommunication Engineering • Post Graduate Degree in Odia Literature • Masters Degree in Mass Communications and Advanced Journalism from Utkal University, Odisha • Ph.D in literature from Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Residence: Nilima Nilaya, 421/2359, Padmabati Vihar Sailashree Vihar, Bhubaneswar - 751 021, Odisha. Cell: +91 9937220229 / 9437014119 Office: Kadambini Villa, 421/2358, Padmabati Vihar Sailashree Vihar, Bhubaneswar - 751 021, Odisha. Tel: +91 7328841932 / 7328841933, 0674-2740519 / 2741260 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Website: https://itisamanta.com & https://kadambini.org Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Itirani_Samanta Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/ItiraniSamantaOfficial Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/itiranisamanta 2 Dr. Itirani Samanta, an eminent writer, journalist, editor, publisher and national award winning film producer occupies a very signficant position in contemporary Odisha. Writing is her first love. In fact, from early childhood, she started cuddling up emotions and scribbled down her feelings on a regular basis. That in later stage culminated into stories, novels, poems, dramas, features, articles of social relevance, women empowerment & gender related issues. She has been continuously writing her editorials in ‘The Kadambini’, the most popular family magazine in Odisha on women related issues, women empowerment and current social problems since two decade. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXX NO. 8 MARCH - 2014 PRADEEP KUMAR JENA, I.A.S. Principal Secretary PRAMOD KUMAR DAS, O.A.S.(SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Sri Krsna - Jagannath Consciousness : Vyasa - Jayadeva - Sarala Dasa Dr. Satyabrata Das ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 Classical Language : Odia Subrat Kumar Prusty ... 4 Language and Language Policy in India Prof. Surya Narayan Misra ... 14 Rise of the Odia Novel : 1897-1930 Jitendra Narayan Patnaik ... 18 Gangadhar Literature : A Bird’s Eye View Jagabandhu Panda ... 23 Medieval Odia Literature and Bhanja Dynasty Dr. Sarat Chandra Rath ... 25 The Evolution of Odia Language : An Introspection Dr. Jyotirmati Samantaray ... 29 Biju - The Greatest Odia in Living Memory Rajkishore Mishra ... 31 Binode Kanungo (1912-1990) - A Versatile Genius ... 34 Role of Maharaja Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo in the Odia Language Movement Harapriya Das Swain ... 38 Odissi Vocal : A Unique Classical School Kirtan Narayan Parhi .. -

Importance of Eco-Literature in Odia Short Stories

www.ijcrt.org © 2019 IJCRT | Volume 7, Issue 2 May 2019 | ISSN: 2320-2882 IMPORTANCE OF ECO-LITERATURE IN ODIA SHORT STORIES Dr Banaja Basini Barik Department of Odia B.N.M.A. College, Paliabindha, Bhadrak, Odisha, India ABSTRACT At present the people of whole world are in a mood to save the earth which is going to be spoiled soon. Scientists, philosophers, thinkers, Earth scientists are searching into the matter how to save the environment. They feel the tragedy of the earth which is somehow going to be submerged in the waters. To make the common people conscious about this, they feel the literature is the way through which the people of the world can be come to know about it and realized present state of acute situation of the environment. So it is need of the hour to convey the mankind about the devastating picture of the earth that is going to be happened soon. So worldwide consciousness in this context is badly necessary at present for literature and electronic media are mostly helpful. So there is the need of the eco-literature which can be sponsored around the earth for the survival of the mankind. KEYWORDS: Ecoliterature, afforestation, nature, ecology, forest etc. INTRODUCTION Since the start of the human life on the earth man has been closely related with the nature around him. So all of his activities and actions linked with life processes are also linked to the nature. He gets all sorts of his requirements from nature for his development, living and civilization. That is why nature supplies all kinds of nutrients for growth and progress of human life on the earth. -

Ocs-2015-Syllabus-F0db7a3a.Pdf

Syllabi for the Odisha Civil Services (Main) Examination (Subject-wise) SYLLABUS FOR ODISHA CIVIL SERVICES (MAIN) EXAMINATION ODIA LANGUAGE The aim of the paper is to test the candidate’s ability to understand serious discursive prose and express his ideas clearly and correctly in Odia language. The pattern of questions would broadly be as follows:- Comprehension of a given passage .. 30 Marks Precis writing with a passage of around 1000 words .. 40 Marks Translation from English to Odia .. 30 Marks Grammar, usage and vocabulary .. 80 Marks Short Essay of around 1000 words .. 100 Marks Expansion of an idea .. 20 Marks Total .. 300 Marks ENGLISH The aim of the paper is to test the candidate’s ability to understand serious discursive prose and express his ideas clearly and correctly in English language. The pattern of questions would broadly be as follows :- Comprehension of a given passage .. 30 Marks Precis writing with a passage of around 1000 words .. 40 Marks Translation from Odia to English .. 30 Marks Grammar, usage and vocabulary .. 80 Marks Short Essay of around 1000 words .. 100 Marks Expansion of an idea .. 20 Marks Total .. 300 Marks ENGLISH ESSAY GENERAL INSTRUCTION Candidates will be required to write an Essay on a specific topic. The choice of subjects will be given. They will be expected to keep closely to the subject of the essay to arrange their ideas in orderly fashion and to write concisely. Credit will be given for effective and exact expression. GENERAL STUDIES The nature and standard of questions in this paper will be such that a well educated person will be able to answer them without any specialized study. -

Odia Identity, Language and Regionalism: a Historical Perspective

IAR Journal of Humanities and Social Science ISSN Print : 2708-6259 | ISSN Online : 2708-6267 Frequency: Bi-Monthly Language: Multilingual Origin: KENYA Website : https://www.iarconsortium.org/journal-info/IARJHSS Review Article Odia Identity, Language and Regionalism: A Historical Perspective Article History Abstract: The Odisha had a rich heritage in sphere of culture, religion, politics, and economy. They could maintain the same till they came contact with outsiders. However the Received: 18.12.2020 decay in all aspects started during the British Rule. The main aim of the paper is to Revision: 03.01.2021 understand the historical development of Odia language particularly in the colonial period Accepted: 29.01.2021 which in the later time formed the separate state basing on language. The Odia who could realize at the beginning of the 20th century proved their mettle in forming the Published: 15.02.2021 Odisha province in 1936 and amalgamating Garhjat States in 1948 and 1950. Equally there Author Details are huge literature in defending the Odia language and culture by Odia and non-Odia writers Laxmipriya Palai and activists of the century. Similarly, from the beginning of the 20th century and with the growth of Odia nationalism, the Odias had to struggle for formation of Odisha with the Authors Affiliations amalgamation of Odia speaking tracts from other province and play active role in freedom P.G. Dept. of History, Berhampur University, movement. Berhampur-760007, Odisha, India Keywords: Odia, language, identity, regionalism, amalgamation, movement, culture. Corresponding Author* Laxmipriya Palai How to Cite the Article: INTRODUCTION Laxmipriya Palai (2021); Odia Identity, Language By now, we have enough literature on how there was a systematic and Regionalism: A Historical Perspective .