Stories by K*^S* Das

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications MONOGRAPHS (MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE) Amrita Pritam (Punjabi writer) By Sutinder Singh Noor Pp. 96, Rs. 40 First Edition: 2010 ISBN 978-81-260-2757-6 Amritlal Nagar (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Narinder Bhullar Pp. 116, First Edition: 1996 ISBN 81-260-0088-0 Rs. 15 Baba Farid (Punjabi saint-poet) By Balwant Singh Anand Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 88, Reprint: 1995 Rs. 15 Balwant Gargi (Punjabi Playright) By Rawail Singh Pp. 88, Rs. 50 First Edition: 2013 ISBN: 978-81-260-4170-1 Bankim Chandra Chatterji (Bengali novelist) By S.C. Sengupta Translated by S. Soze Pp. 80, First Edition: 1985 Rs. 15 Banabhatta (Sanskrit poet) By K. Krishnamoorthy Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 96, First Edition: 1987 Rs. 15 Bhagwaticharan Verma (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Baldev Singh ‘Baddan’ Pp. 96, First Edition: 1992 ISBN 81-7201-379-5 Rs. 15 Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha (Punjabi scholar and lexicographer) By Paramjeet Verma Pp. 136, Rs. 50.00 First Edition: 2017 ISBN: 978-93-86771-56-8 Bhai Vir Singh (Punjabi poet) By Harbans Singh Translated by S.S. Narula Pp. 112, Rs. 15 Second Edition: 1995 Bharatendu Harishchandra (Hindi writer) By Madan Gopal Translated by Kuldeep Singh Pp. 56, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1984 Bharati (Tamil writer) By Prema Nand kumar Translated by Pravesh Sharma Pp. 103, Rs.50 First Edition: 2014 ISBN: 978-81-260-4291-3 Bhavabhuti (Sanskrit poet) By G.K. Bhat Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 80, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1983 Chandidas (Bengali poet) By Sukumar Sen Translated by Nirupama Kaur Pp. -

E:\ANNUAL REPORT-2019.Pmd

ESTD-1949 (1949-2019) 70th Anniversary Day 17th April, 2019 Tinkonia Bagicha - 753001 1 HOMAGE TO CHIEF PATRON Late Narendra Kumar Mitra FOUNDER MEMBERS Late (Dr.) Haridas Gupta Late Satyanarayan Gupta Late Preety Mallik Smt. Ila Gupta REMEMBRANCE (OUR SENIOR ASSOCIATES) 1. Late Sushil Ch. Gupta 12. Late Subrata Gupta 2. Late Nirupama Mitra 13. Late Robin Kundu 3. Late Sovana Basu 14. Late Nemailal Bose 4. Late Nanibala Roy Choudhury 15. Late Pranab Kumar Mitra 5. Late Ram Chandra Kar 16. Late Jishnu Roy 6. Late Narendra Ch. Mohapatra 17. Late Amal Krishna Roy(Adv.) 7. Late Sarat Kumar Mitra 18. Late Tripty Mitra 8. Late Subodh Ch. Ghose 19. Late Surya Narayan Acharya 9. Late Sunil Kumar Sen 20. Late Tarun Kumar Mitra 10. Late Renendra Ku. Mitra 21. Late Debal Kumar Mitra 11. Late Sanat Ku. Mitra LIST OF THE PAST LIFE TIME DEDICATED AWARDEE YEAR NAME OF THE AWARDEE DESIGNATION 2009 SMT. ILA GUPTA FOUNDER MEMBER 2010 LATE PRITY MALLIK(POSTHUMOUS) FOUNDER MEMBER 2011 LATE SATYA NARAYAN GUPTA FOUNDER MEMBER 2011 LATE (DR.) HARIDAS GUPTA FOUNDER MEMBER 2 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE LIBRARY President : Sri Prafulla Ch. Pattanayak Vice-President : Sri Tarak Nath Sur Secretary : Sri Sandip Kumar Mitra Treasurer : Sri Debraj Mitra MEMBERS 1. Sri Pratap Ch. Das 7. Sri Prasun Kumar Das 2. Sri Sunil Kumar Gupta 8. Smt. Anushree Dasgupta 3. Sri Shyamal Kumar Mitra 9. Sri Indranil Mitra 4. Sri Dilip Kumar Mitra 10. Smt. Barnali Ghosh 5. Smt. Tanushree Ghose 11. Sri Santanu Mitra 6. Sri Swapan Kumar Dasgupta 12. Sri Dipanjan Mitra LIST OF THE CHIEF GUEST WHO GRACED THE OCCASION IN THE PAST 1950 : Sri Lalit Kumar Das Gupta, Advocate 1951 : Sri Lingaraj Mishra, M.P. -

DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY ENGLISH by SUKANTI MOHAPATRA Dr. SARBESWAR SAMAL Hon. D. Litt

THE SPIRITUAL AND PSYCHIC ELEMENTS IN THE STORIES OF MANOJ DAS THIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UTKAL UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH BY SUKANTI MOHAPATRA RESEARCH GUIDE Dr. SARBESWAR SAMAL Hon. D. Litt. [USA] READER IN ENGLISH (RETD.) 2008 TOPIC CERTIFICATE Dr. Sarbeswar Samal, Dr. Sarbeswar Samal Hons. D. Litt. (USA) Hon. D. Litt (USA) Reader in English (Retd.) Plot No:- 15 Annapurna Ravenshaw College Residential Complex, (Autonomous) Cuttack Shelter Square Tulasipur, Cuttack This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Spiritual and Psychic Elements in the Stories of Manoj Das” being submitted by Sukanti Mohapatra, Lecturer in English, Maharishi College of Natural Law, Bhubaneswar, for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in English, of Utkal University, is a bonafide research work carried out by her under my supervision and guidance. The thesis is of the standard fulfilling the requirements of the regulation relating to the degree and it has not been submitted to any other University or Institute for the award of any degree or diploma. (Dr. Sarbeswar Samal) AREA CERTIFICATE Dr. Sarbeswar Samal, Hons. D. Litt. (USA) Reader in English (Retd.) Ravenshaw College (Autonomous) Cuttack This is to certify that the thesis entitled ―The Spiritual and Psychic Elements in the Stories of Manoj Das‖ prepared by Sukanti Mohapatra under my guidance is original and it is within the area of registration. (Dr. Sarbeswar Samal) DECLARATION I declare that this thesis entitled ―The Spiritual and Psychic Elements in the Stories of Manoj Das‖ is a product of original research done by me and it has not been submitted to any other University/Institute for doctoral degree. -

Sahitya Akademi

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2004 SAHITYA AKADEMI Orissa Sahitya Akademi an institution of letters was established in the year 1957 for work actively for the development of Oriya Language and Literature and to set high literary standards to foster and co-ordinate literary activities and to promote through them all, the cultural unity of the State. AIMS & OBJECTIVES (i) to promote co-operation among men of letters and literary associations, Universities and cultural organisations and to encourage the establishment and development of representative literary associations concerned with the advancement of Oriya literature; (ii) to encourage or to arrange translation of literary works from different Indian languages into Oriya and also from foreign languages into Oriya and vice verse; (iii) to publish or to assist associations and individuals in publishing literary works including bibliographies, dictionaries, bilingual or multilingual encyclopaedias, basic vocabularies etc., in the Oriya Language and also publishing literary journals, reviews and lists of publications in Oriya; (iv) to sponsor or to hold literary conference, seminars and exhibitions; (v) to award prizes and distinctions and to give recognition to individual writers for outstanding works. (vi) to promote research in Oriya language and literature and to encourage the propagation and study of such literature; (vii) to improve and develop the Oriya and other scripts in use in Orissa and to encourage publication of selected books in Oriya Language in the Devanagari Script; (viii) -

The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue1 Ser. II || Jan, 2020 || PP 01-04 The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature Dr. Ajay Kumar Panda Sr. Lecturer in Odia Upendranath College, Soro, Balasore, Odisha ABSTRACT : Feminism, in literature as well as otherwise, began as an expression of dissatisfaction regarding the attitude of the society towards the identity and rights of women. However, slowly, it evolved to empower women to make her financially, socially and psychologically independent. In the field of literature, it evolved to finally enable the female writers to be free from the influence of male writers as well as the social norms that suggested different standards for male and female KEYWORDS – Feminism, identity and rights of women, empower women, free from the influence of male writers ,Sita, Draupadi,Balaram Das, Vaishanbism, Panchasakha, Kuntala Kumari, Rama Devi, Sarala Devi, Nandini Satapathy, Prativa Ray,Pratiova Satapathy, Sarojini Sahu.Ysohodhara Mishra ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ --------------- Date of Submission: 18-01-2020 Date of Acceptance: 06-02-2020 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION: Feminism in Indian literature, as can be most commonly conceived is a much sublime and over-the-top concept, -

Four Major Modern Oriya Novelists

Orissa Review * November - 2008 Four Major Modern Oriya Novelists Jitendra Narayan Patnaik While the first major event in the hundred-and- Panigrahi also wrote five novels, four of them twenty-year old history of the Oriya novel is the having been published in the nineteen-thirties and publication of Fakir Mohan Senapati's Cha Mana nineteen-forties. His first novel, Matira Manisha, Atha Guntha in 1897, its full potential as a published in 1931, is considered a modern classic legitimate literary form was realized during and in Oriya language. Its film version, directed by after the nineteen-thirties when Gandhian and Mrinal Sen, was a great success and won a Marxist ideologies as well as the politics of number of national awards. The plot revolves resistance against colonial power and a pervasive round the family of Shama Pradhan, a rural farmer sense of social reform in the wake of exposure to and his two sons, Baraju and Chakadi. At the modern educational system led to a renewed time of his death, Shama Pradhan entrusts Baraju vision of social and historical forces that found with the responsibility of looking after his younger felicity of expression in the new fictional form of son Chakadi and entreats him to prevent partition the prose narrative. The four novelists discussed of land and the house between the two brothers. in this paper began writing in the nineteen-thirties Baraju is a peace-loving person who commands and nineteen-forties and while three of them--- respect from the villagers for his idealistic way of Kanhu Charan Mohanty, Gopinath Mohanty and life. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXX NO. 8 MARCH - 2014 PRADEEP KUMAR JENA, I.A.S. Principal Secretary PRAMOD KUMAR DAS, O.A.S.(SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Sri Krsna - Jagannath Consciousness : Vyasa - Jayadeva - Sarala Dasa Dr. Satyabrata Das ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 Classical Language : Odia Subrat Kumar Prusty ... 4 Language and Language Policy in India Prof. Surya Narayan Misra ... 14 Rise of the Odia Novel : 1897-1930 Jitendra Narayan Patnaik ... 18 Gangadhar Literature : A Bird’s Eye View Jagabandhu Panda ... 23 Medieval Odia Literature and Bhanja Dynasty Dr. Sarat Chandra Rath ... 25 The Evolution of Odia Language : An Introspection Dr. Jyotirmati Samantaray ... 29 Biju - The Greatest Odia in Living Memory Rajkishore Mishra ... 31 Binode Kanungo (1912-1990) - A Versatile Genius ... 34 Role of Maharaja Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo in the Odia Language Movement Harapriya Das Swain ... 38 Odissi Vocal : A Unique Classical School Kirtan Narayan Parhi .. -

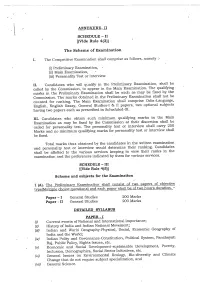

Ocs-2015-Syllabus-F0db7a3a.Pdf

Syllabi for the Odisha Civil Services (Main) Examination (Subject-wise) SYLLABUS FOR ODISHA CIVIL SERVICES (MAIN) EXAMINATION ODIA LANGUAGE The aim of the paper is to test the candidate’s ability to understand serious discursive prose and express his ideas clearly and correctly in Odia language. The pattern of questions would broadly be as follows:- Comprehension of a given passage .. 30 Marks Precis writing with a passage of around 1000 words .. 40 Marks Translation from English to Odia .. 30 Marks Grammar, usage and vocabulary .. 80 Marks Short Essay of around 1000 words .. 100 Marks Expansion of an idea .. 20 Marks Total .. 300 Marks ENGLISH The aim of the paper is to test the candidate’s ability to understand serious discursive prose and express his ideas clearly and correctly in English language. The pattern of questions would broadly be as follows :- Comprehension of a given passage .. 30 Marks Precis writing with a passage of around 1000 words .. 40 Marks Translation from Odia to English .. 30 Marks Grammar, usage and vocabulary .. 80 Marks Short Essay of around 1000 words .. 100 Marks Expansion of an idea .. 20 Marks Total .. 300 Marks ENGLISH ESSAY GENERAL INSTRUCTION Candidates will be required to write an Essay on a specific topic. The choice of subjects will be given. They will be expected to keep closely to the subject of the essay to arrange their ideas in orderly fashion and to write concisely. Credit will be given for effective and exact expression. GENERAL STUDIES The nature and standard of questions in this paper will be such that a well educated person will be able to answer them without any specialized study. -

Odia Identity, Language and Regionalism: a Historical Perspective

IAR Journal of Humanities and Social Science ISSN Print : 2708-6259 | ISSN Online : 2708-6267 Frequency: Bi-Monthly Language: Multilingual Origin: KENYA Website : https://www.iarconsortium.org/journal-info/IARJHSS Review Article Odia Identity, Language and Regionalism: A Historical Perspective Article History Abstract: The Odisha had a rich heritage in sphere of culture, religion, politics, and economy. They could maintain the same till they came contact with outsiders. However the Received: 18.12.2020 decay in all aspects started during the British Rule. The main aim of the paper is to Revision: 03.01.2021 understand the historical development of Odia language particularly in the colonial period Accepted: 29.01.2021 which in the later time formed the separate state basing on language. The Odia who could realize at the beginning of the 20th century proved their mettle in forming the Published: 15.02.2021 Odisha province in 1936 and amalgamating Garhjat States in 1948 and 1950. Equally there Author Details are huge literature in defending the Odia language and culture by Odia and non-Odia writers Laxmipriya Palai and activists of the century. Similarly, from the beginning of the 20th century and with the growth of Odia nationalism, the Odias had to struggle for formation of Odisha with the Authors Affiliations amalgamation of Odia speaking tracts from other province and play active role in freedom P.G. Dept. of History, Berhampur University, movement. Berhampur-760007, Odisha, India Keywords: Odia, language, identity, regionalism, amalgamation, movement, culture. Corresponding Author* Laxmipriya Palai How to Cite the Article: INTRODUCTION Laxmipriya Palai (2021); Odia Identity, Language By now, we have enough literature on how there was a systematic and Regionalism: A Historical Perspective . -

Odisha Sahitya Academy Awarded Books and Writers

ODISHA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2011 ODISHA SAHITYA ACADEMY AWARDED BOOKS AND WRITERS Sl. Name of the Book Category Name of Writers No. 1957-1958 1. Dilip Lyric Poem Sri Upendra Mohanty 2. Swarna Yugara Sandhana Play Sri Gyaneendra Burma 3. Agnee Parikshya Play Shri Bhanjakishore Patnaik 4. Vyasakabi Fakir Mohan Criticism Shri Natabar Samantaray 5. Veda Manushya Kruta Ki ? Criticism Shri Priyabrata Das 6. Godan Translation Golakha Bihari Dhal 7. Ajara Pound Kabita Translation Shri Gyaneendra Burma 8. Sabujapatra O Dhusara Golap Story Shri Surendra Mohanty 9. Chora Chaitali Story Smt. Rajeswari Dalbehera 10. Kanta O Phula Poetry Shri Godabarish Mohapatra 11. Sanchayan Poetry Smt. Bidyutprabha Devi 12. Bhagaban Sankaracharya Biography Shri Durga Charan Mohanty 13. Jateeya Jeebanara Atmabikash Biography Shri Gobinda Chandra Mishra 14. Odishi Chitra Science Literature Shri Binod Routray 15. Puspa Chasha Science Literature Shri Biswanath Sahoo 16. Kalinga Kahani Child Literature Smt. Kanaka Manjari Mohapatra 17. Pilanka Katha Lahari Child Literature Shri Chandra Sekhar Mohapatra 18. Europere Mo Anubhuti Travel Story Sriram Chandra Das 1959-1961 19. Aranyak Story Shri Manoj Das 20. Ootha Kankal Poetry Late Godabarish Mohapatra 21. Pashchima Diganta Travel Story Shri Shriharsha Mishra 22. E Jugara Shrestha Abiskar Science Literature Shri Gokulananda Mohapatra 23. Jeeban Bidyalaya Essay Shri Chittaranjan Das 24. Juga Prabarttak Radhanath Criticism Shri Natabar Samantaray 25. Kabi Samrat Upendra Bhanja Criticism Shri Ananta Padmanav Patnaik 26. Charam Patra Poetry Shri Rabindra Nath Singh 27. Nar Kinnar Novel Shri Shantanu Ku.Acharya 1962-1964 28. Adi Manabara Itibrutta Story Shri Kamal Lochan Baral 29. Satyabhama Lyric Poem Shri Golak Chandra Pradhan 30.