The 'Beshya' and the 'Bahu': Re-Reading Fakir Mohan Senapati's “Patent Medicine”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue1 Ser. II || Jan, 2020 || PP 01-04 The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature Dr. Ajay Kumar Panda Sr. Lecturer in Odia Upendranath College, Soro, Balasore, Odisha ABSTRACT : Feminism, in literature as well as otherwise, began as an expression of dissatisfaction regarding the attitude of the society towards the identity and rights of women. However, slowly, it evolved to empower women to make her financially, socially and psychologically independent. In the field of literature, it evolved to finally enable the female writers to be free from the influence of male writers as well as the social norms that suggested different standards for male and female KEYWORDS – Feminism, identity and rights of women, empower women, free from the influence of male writers ,Sita, Draupadi,Balaram Das, Vaishanbism, Panchasakha, Kuntala Kumari, Rama Devi, Sarala Devi, Nandini Satapathy, Prativa Ray,Pratiova Satapathy, Sarojini Sahu.Ysohodhara Mishra ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ --------------- Date of Submission: 18-01-2020 Date of Acceptance: 06-02-2020 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION: Feminism in Indian literature, as can be most commonly conceived is a much sublime and over-the-top concept, -

Strategies for Combating the Culture of Dowry and Domestic Violence in India

pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com "Violence against women: Good practices in combating and eliminating violence against women" Expert Group Meeting Organized by: UN Division for the Advancement of Women in collaboration with: UN Office on Drugs and Crime 17 to 20 May 2005 Vienna, Austria Strategies for Combating the Culture of Dowry and Domestic Violence in India Expert paper prepared by: Madhu Purnima Kishwar Manushi, India 1 This paper deals with the varied strategies used by Manushi and other women’s organizations to deal with issues of domestic violence, the strengths and limitations of approaches followed hitherto and strategies I think might work far better than those tried so far. However, at the very outset I would like to clarify that even though Manushi played a leading role in bringing national attention to domestic violence and the role dowry has come to play in making women’s lives vulnerable, after nearly 28 years of dealing with these issues, I have come to the firm conclusion that terms “dowry death” and “dowry violence” are misleading. They contribute towards making domestic violence in India appear as unique, exotic phenomenon. They give the impression that Indian men are perhaps the only one to use violence out of astute and rational calculations. They alone beat up women because they get rewarded with monetary benefits, whereas men in all other parts of the world beat their wives without rhyme or reason, without any benefits accruing to them. Domestic violence is about using brute force to establish power relations in the family whereby women are taught and conditioned to accepting a subservient status for themselves. -

Four Major Modern Oriya Novelists

Orissa Review * November - 2008 Four Major Modern Oriya Novelists Jitendra Narayan Patnaik While the first major event in the hundred-and- Panigrahi also wrote five novels, four of them twenty-year old history of the Oriya novel is the having been published in the nineteen-thirties and publication of Fakir Mohan Senapati's Cha Mana nineteen-forties. His first novel, Matira Manisha, Atha Guntha in 1897, its full potential as a published in 1931, is considered a modern classic legitimate literary form was realized during and in Oriya language. Its film version, directed by after the nineteen-thirties when Gandhian and Mrinal Sen, was a great success and won a Marxist ideologies as well as the politics of number of national awards. The plot revolves resistance against colonial power and a pervasive round the family of Shama Pradhan, a rural farmer sense of social reform in the wake of exposure to and his two sons, Baraju and Chakadi. At the modern educational system led to a renewed time of his death, Shama Pradhan entrusts Baraju vision of social and historical forces that found with the responsibility of looking after his younger felicity of expression in the new fictional form of son Chakadi and entreats him to prevent partition the prose narrative. The four novelists discussed of land and the house between the two brothers. in this paper began writing in the nineteen-thirties Baraju is a peace-loving person who commands and nineteen-forties and while three of them--- respect from the villagers for his idealistic way of Kanhu Charan Mohanty, Gopinath Mohanty and life. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXX NO. 8 MARCH - 2014 PRADEEP KUMAR JENA, I.A.S. Principal Secretary PRAMOD KUMAR DAS, O.A.S.(SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Sri Krsna - Jagannath Consciousness : Vyasa - Jayadeva - Sarala Dasa Dr. Satyabrata Das ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 Classical Language : Odia Subrat Kumar Prusty ... 4 Language and Language Policy in India Prof. Surya Narayan Misra ... 14 Rise of the Odia Novel : 1897-1930 Jitendra Narayan Patnaik ... 18 Gangadhar Literature : A Bird’s Eye View Jagabandhu Panda ... 23 Medieval Odia Literature and Bhanja Dynasty Dr. Sarat Chandra Rath ... 25 The Evolution of Odia Language : An Introspection Dr. Jyotirmati Samantaray ... 29 Biju - The Greatest Odia in Living Memory Rajkishore Mishra ... 31 Binode Kanungo (1912-1990) - A Versatile Genius ... 34 Role of Maharaja Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo in the Odia Language Movement Harapriya Das Swain ... 38 Odissi Vocal : A Unique Classical School Kirtan Narayan Parhi .. -

Ganga As Perceived by Some Ganga Lovers Mother Ganga's Rights Are Our Rights

Ganga as Perceived by Some Ganga Lovers Mother Ganga’s Rights Are Our Rights Pujya Swami Chidanand Saraswati Nearly 500 million people depend every day on the Ganga and Her tributaries for life itself. Like the most loving of mothers, She has served us, nourished us and enabled us to grow as a people, without hesitation, without discrimination, without vacation for millennia. Regardless of what we have done to Her, the Ganga continues in Her steady fl ow, providing the waters that offer nourishment, livelihoods, faith and hope: the waters that represents the very life-blood of our nation. If one may think of the planet Earth as a body, its trees would be its lungs, its rivers would be its veins, and the Ganga would be its very soul. For pilgrims, Her course is a lure: From Gaumukh, where she emerges like a beacon of hope from icy glaciers, to the Prayag of Allahabad, where Mother Ganga stretches out Her glorious hands to become one with the Yamuna and Saraswati Rivers, to Ganga Sagar, where She fi nally merges with the ocean in a tender embrace. As all oceans unite together, Ganga’s reach stretches far beyond national borders. All are Her children. For perhaps a billion people, Mother Ganga is a living goddess who can elevate the soul to blissful union with the Divine. She provides benediction for infants, hope for worshipful adults, and the promise of liberation for the dying and deceased. Every year, millions come to bathe in Ganga’s waters as a holy act of worship: closing their eyes in deep prayer as they reverently enter the waters equated with Divinity itself. -

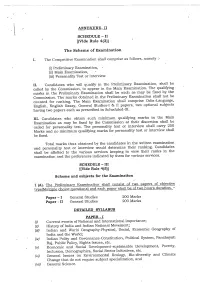

Ocs-2015-Syllabus-F0db7a3a.Pdf

Syllabi for the Odisha Civil Services (Main) Examination (Subject-wise) SYLLABUS FOR ODISHA CIVIL SERVICES (MAIN) EXAMINATION ODIA LANGUAGE The aim of the paper is to test the candidate’s ability to understand serious discursive prose and express his ideas clearly and correctly in Odia language. The pattern of questions would broadly be as follows:- Comprehension of a given passage .. 30 Marks Precis writing with a passage of around 1000 words .. 40 Marks Translation from English to Odia .. 30 Marks Grammar, usage and vocabulary .. 80 Marks Short Essay of around 1000 words .. 100 Marks Expansion of an idea .. 20 Marks Total .. 300 Marks ENGLISH The aim of the paper is to test the candidate’s ability to understand serious discursive prose and express his ideas clearly and correctly in English language. The pattern of questions would broadly be as follows :- Comprehension of a given passage .. 30 Marks Precis writing with a passage of around 1000 words .. 40 Marks Translation from Odia to English .. 30 Marks Grammar, usage and vocabulary .. 80 Marks Short Essay of around 1000 words .. 100 Marks Expansion of an idea .. 20 Marks Total .. 300 Marks ENGLISH ESSAY GENERAL INSTRUCTION Candidates will be required to write an Essay on a specific topic. The choice of subjects will be given. They will be expected to keep closely to the subject of the essay to arrange their ideas in orderly fashion and to write concisely. Credit will be given for effective and exact expression. GENERAL STUDIES The nature and standard of questions in this paper will be such that a well educated person will be able to answer them without any specialized study. -

6. Yes to Sita, No to Ram-24.8.06.Pmd

wish to clarify at the outset that I am going to focus primarily on the ISita of popular imagination rather than the Sita of Tulsi, Balmiki or any other textual or oral version of the Yes to Sita, No to Ram! Ramayan. Therefore, I deliberately refrain from detailed textual analysis. The Continuing Popularity of Sita in India I have focused on how her life is inter- preted and sought to be emulated in today’s context. Madhu Kishwar However, there is no escaping the fact that in north India the Sita of popu- lar imagination has been deeply influ- enced by the Sita of Ramcharit Manas study carried out in Uttar Pradesh, 500 was a 1957 survey. However, Sita con- by Tulsi. In most other versions of boys and 360 girls between the ages tinues to command similar reverence the Ramayan, close companionship of 9 and 22 years were asked to select even today, even among modern edu- and joyful togetherness of the couple the ideal woman from a list of 24 names cated people in India. This paper is a are the most prominent features of the of gods, goddesses, heroes, and hero- preliminary exploration into why Sita Ram-Sita relationship rather than her ines of history. Sita was seen as the continues to exercise such a powerful self-effacing devotion and loyalty ideal woman by an overwhelming pro- grip on popular imagination, especially which have become the hallmark of portion of the respondents. There among women. the modern day stereotype of Sita. were no age or sex differences.1 That The medieval Ramayan of Tulsi marks A Slavish Wife? the transition from Ram and Sita being I grew up thinking of Sita as a presented as an ideal couple to pro- much wronged woman — a slavish wife jecting each of them as an ideal man without a mind of her own. -

Odia Identity, Language and Regionalism: a Historical Perspective

IAR Journal of Humanities and Social Science ISSN Print : 2708-6259 | ISSN Online : 2708-6267 Frequency: Bi-Monthly Language: Multilingual Origin: KENYA Website : https://www.iarconsortium.org/journal-info/IARJHSS Review Article Odia Identity, Language and Regionalism: A Historical Perspective Article History Abstract: The Odisha had a rich heritage in sphere of culture, religion, politics, and economy. They could maintain the same till they came contact with outsiders. However the Received: 18.12.2020 decay in all aspects started during the British Rule. The main aim of the paper is to Revision: 03.01.2021 understand the historical development of Odia language particularly in the colonial period Accepted: 29.01.2021 which in the later time formed the separate state basing on language. The Odia who could realize at the beginning of the 20th century proved their mettle in forming the Published: 15.02.2021 Odisha province in 1936 and amalgamating Garhjat States in 1948 and 1950. Equally there Author Details are huge literature in defending the Odia language and culture by Odia and non-Odia writers Laxmipriya Palai and activists of the century. Similarly, from the beginning of the 20th century and with the growth of Odia nationalism, the Odias had to struggle for formation of Odisha with the Authors Affiliations amalgamation of Odia speaking tracts from other province and play active role in freedom P.G. Dept. of History, Berhampur University, movement. Berhampur-760007, Odisha, India Keywords: Odia, language, identity, regionalism, amalgamation, movement, culture. Corresponding Author* Laxmipriya Palai How to Cite the Article: INTRODUCTION Laxmipriya Palai (2021); Odia Identity, Language By now, we have enough literature on how there was a systematic and Regionalism: A Historical Perspective . -

Ramayan Ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu Way of Life and the Contribution of Hindu Women, Amongst Others

Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) Mahila Shibir 2020 East and South Midlands Vibhag FOREWORD INSPIRING AND UNPRECEDENTED INITIATIVE In an era of mass consumerism - not only of material goods - but of information, where society continues to be led by dominant and parochial ideas, the struggle to make our stories heard, has been limited. But the tides are slowly turning and is being led by the collaborative strength of empowered Hindu women from within our community. The Covid-19 pandemic has at once forced us to cancel our core programs - which for decades had brought us together to pursue our mission to develop value-based leaders - but also allowed us the opportunity to collaborate in other, more innovative ways. It gives me immense pride that Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) have set a new precedent for the trajectory of our work. As a follow up to the successful Mahila Shibirs in seven vibhags attended by over 500 participants, 342 Mahila sevikas came together to write 411 articles on seven different topics which will be presented in the form of seven e-books. I am very delighted to launch this collection which explores topics such as: The uniqueness of Bharat, Ramayan ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu way of life and The contribution of Hindu women, amongst others. From writing to editing, content checking to proofreading, the entire project was conducted by our Sevikas. This project has revealed hidden talents of many mahilas in writing essays and articles. We hope that these skills are further encouraged and nurtured to become good writers which our community badly lacks. -

Ramayana: a Divine Drama Actors in the Divine Play As Scripted by Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Ramayana: A Divine Drama Actors in the Divine Play as scripted by Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Volume I Compiled by Tumuluru Krishna Murty Edited by Desaraju Sri Sai Lakshmi © Tumuluru Krishna Murty ‘Anasuya’ C-66 Durgabai Deshmukh Colony Ahobil Mutt Road Hyderabad 500007 Ph: +91 (40) 2742 7083/ 8904 Typeset and formatted by: Desaraju Sri Sai Lakshmi Cover Designed by: Insty Print 2B, Ganesh Chandra Avenue Kolkata - 700013 Website: www.instyprint.in VOLUME I No one can shake truth; no one can install untruth. No one can understand My mystery. The best you can do is get immersed in it. The mysterious, indescribable power has come within the reach of all. No one is born and allowed to live for the sake of others. Each has their own burden to carry and lay down. - Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Put all your burdens on Me. I have come to bear it, so that you can devote yourselves to Sadhana TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR VOLUME I PRAYERS 11 1. SAMARPANAM 17 2. EDITORIAL COMMENTS 27 3. THE ESSENCE OF RAMAYANA 31 4. IKSHVAKU DYNASTY-THE IMPERIAL LINE 81 5. DASARATHA AND HIS CONSORTS 117 118 5.1 DASARATHA 119 5.2 KAUSALYA 197 5.3 SUMITRA 239 5.4 KAIKEYI 261 INDEX 321 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS FIGURE 1: DESCENT OF GANGA 113 FIGURE 2: PUTHRAKAMESHTI YAGA 139 FIGURE 3: RAMA TAKING LEAVE OF DASARATHA 181 FIGURE 4: DASARATHA SEES THE FATALLY INJURED SRAVANA 191 PRAYERS Vaamaankasthitha Jaanaki parilasat kodanda dandaamkare Chakram Chordhva karena bahu yugale samkham saram Dakshine Bibranam Jalajadi patri nayanam Bhadradri muurdhin sthitham Keyuradi vibhushitham Raghupathim Soumitri Yuktham Bhaje!! - Adi Sankara.