Forgotten Irish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANALYSIS of 2011 CENSUS DATA Irish Community Statistics, England and Selected Urban Areas

ANALYSIS OF 2011 CENSUS DATA Irish Community Statistics, England and Selected Urban Areas REPORT FOR NORTH WEST Louise Ryan, Alessio D’Angelo, Michael Puniskis, Neil Kaye July 2014 Supported and funded by: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Irish in Britain is funded by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through the Emigrant Support Programme (ESP). The ESP supports Irish communities overseas by funding non-profit organisations and projects; allowing the development of more strategic links with the global Irish and support of frontline welfare services that help the most vulnerable members of Irish communities overseas. The Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC) at Middlesex University, set up 1990, is a dynamic research centre with a proven track record of delivering projects on time and on budget. The centre draws together a range of staff with expertise in social policy, migration, health, care, welfare and service provision, education, the needs of families, women, children, religion, culture and identity. To view reports from our recent research projects visit our web page: www.sprc.info Irish in Britain is the national representative organisation for the Irish voluntary and community sector across Britain. It provides crucial support and advice to its diverse membership on policy, funding, governance and sustainability. It undertakes research into the needs of the most vulnerable in the community and represents those to Government in Britain and Ireland. Irish in Britain is actively involved in promoting Irish culture, creating Irish -

Who Identifies As Welsh? National

November 2014 DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Who identifies asWelsh? National identities and ethnicity in Wales Summary • In Wales, 1.8 million people identify only as Welsh (58% of • People born in Wales are more likely to report only a Welsh the population) and 218,000 identify as Welsh and British national identity (76%). People born in Oceania and North (7% of the population). America and the Caribbean are more likely to report only a Welsh national identity (14% and 10% respectively) than • Mixed ethnic groups are more likely to identify with only people born in England (8%). a Welsh national identity than all other ethnic minority groups, with the highest proportion being amongst the White and Black Caribbean (59%) group. Introduction Since devolution, the Welsh Government has sought to • Mixed groups are more likely to identify only as Welsh support a common Welsh national identity through the ‘One (47%) than mixed groups in England (46%) and Scotland Wales’ strategy. This has included, for example, strengthening (37%) identify as English or Scottish only. the place of ‘Wales in the World’ and continued support for 1 • The ethnic groups in Wales most likely to identify only as the Welsh language. The inclusion of a question on national British are Bangladeshi (64%), Pakistani (56%) and Black identity in the 2011 Census provides us with an opportunity Caribbean (41%). to examine how people living in Wales describe themselves. The Census shows that 58% of people living in Wales identify • Welsh only national identity is reported more for younger only as Welsh and a further 7% identify as Welsh and British.2 people aged 0 to 17 than those aged 18 or older. -

THE IRISH in BRISTOL, 1938-1985 by Nick Conway BA (Swansea) MA (Liverpool)

1 THE IRISH IN BRISTOL, 1938-1985 by Nick Conway BA (Swansea) MA (Liverpool) Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Arts and Cultural Industries, Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education, University of the West of England August 2018 2 Contents List of Tables and Figures – 4 List of Abbreviations - 5 Abstract – 6 Acknowledgements - 7 Introduction - 8 Research Aims - 9 Research Methodology -9 Definition of terms and census data -13 Importance of the research - 14 Historiography - 18 Chapter 1: Irish Emigration and Bristol - 22 1.1: Leaving Ireland - 23 1.2: The Irish in Bristol - 32 1.3: Patterns of settlement in Bristol - 37 1.4: Experiences of Bristol - 45 1.5: Conclusion - 53 Chapter 2: „Factory and building site fodder‟? - 56 2.1: World War Two workers - 58 2.2: Wartime Irish labour in Bristol - 59 2.3: Transport and housing problems - 61 2.4 Building labourers - 67 2.5 Post-War rebuilding - 68 2.6: NSHC Hostels for Irish building labourers - 72 2.7: Irish nurses in Bristol -79 2.8: Nursing shortages - 83 2.9: The Glenside Irish - 86 2.10: Religious affiliation and geography - 87 2.11: Working at Glenside and further migration - 91 2.12: A positive stereotype? - 92 2.13: Conclusion - 95 Chapter 3: Twentieth century Anglo-Irish relations in the Bristol context - 98 3.1: Irish neutrality - 99 3 3.2: The Treaty Ports - 101 3.3: Loyalists and Nationalists - 104 3.4: Fifth column fears - 107 3.5: The American Note - 110 3.6: Volunteers and emigrants - 111 3.7: Condolences and speeches - 113 3.8: The Republic -

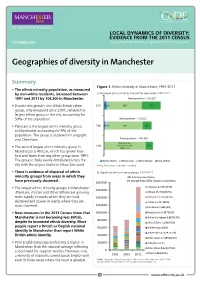

Geographies of Diversity in Manchester

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Manchester Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Manchester, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased between a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 1991 and 2011 by 104,300 in Manchester. Total population – 503,127 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 5% 2% 59% 33% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city, accounting for 59% of the population. Total population – 422,922 • Pakistani is the largest ethnic minority group 2001 2% 4% 74% 19% in Manchester accounting for 9% of the population. The group is clustered in Longsight and Cheetham. Total population – 432,685 85% (includes 1991 White Other and 15% • The second largest ethnic minority group in White Irish Manchester is African, which has grown four- fold and faster than any other group since 1991. The group is fairly evenly distributed across the White Other White Irish White British Non-White city with the largest cluster in Moss Side ward. Notes: Figures may not add due to rounding. • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 minority groups from areas in which they 2011 Census estimates (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. 180,000 • The largest ethnic minority groups in Manchester Pakistani 42,904 (73%) 160,000 (Pakistani, African and Other White) are growing African 25,718 (254%) more rapidly in wards where they are least 140,000 Chinese 13,539 (142%) clustered and slower in wards where they are Indian 11,417 (80%) 120,000 most clustered. -

Forecasting Sub-National Trends in COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake in the UK 2 3 A

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.17.20248382; this version posted April 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 Forecasting sub-national trends in COVID-19 vaccine uptake in the UK 2 3 A. de Figueiredo1,2 4 5 1 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, 6 UK. 7 2 Department of Mathematics, Imperial College London, UK. 8 9 [email protected] 10 11 12 The rollout of COVID-19 vaccines has begun to at-risk populations around the world. It is currently 13 unclear whether rejection of the vaccine will pose challenges for achieving herd/community immunity 14 either through large-scale rejection or localised pockets. Here we predict uptake of the vaccine at 15 unprecedented spatial resolution across the UK using a large-scale survey of over 17,000 individuals. 16 Although the majority of the UK population would likely take the vaccine, there is substantial 17 heterogeneity in uptake intent across the UK. Large urban areas, including London and North West 18 England, females, Black or Black British ethnicities, and Polish-speakers are among the least accepting. 19 This study helps identify areas and socio-demographic groups where vaccination levels may not reach 20 those levels reQuired for herd immunity. Identifying clusters of non-vaccinators is extremely important 21 in the context of achieving herd immunity as vaccination “cold-spots” can amplify epidemic spread and 22 disproportionately increase vaccination levels required for herd protection. -

The Changing Ethnic Profiles of Glasgow and Scotland, and the Implications for Population Health

The changing ethnic profiles of Glasgow and Scotland, and the implications for population health David Walsh September 2017 Acknowledgements Sincere thanks are due to a number of people who have helped with this report and the work that lies behind it. In particular, I would like to thank Duncan Buchanan (ISD Scotland) and Anne Douglas (University of Edinburgh) for their time and patience in various discussions of the SHELS research, as well as for highly useful comments on an earlier draft of the report. I am also extremely grateful to Jackie Erdman (NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde), Colin Fischbacher (ISD Scotland), Gerry McCartney (NHS Health Scotland), Paul Norman (University of Leeds) and Bruce Whyte (GCPH) for additional, and very helpful, comments. Thanks also to Jon Hunter (Scottish Government) for the provision of, and the permission to use, the data reproduced in Figures 8 & 9. Finally, the usual thanks are due to Joe Crossland (GCPH) for invaluable assistance in publishing the report. Contact David Walsh Public Health Programme Manager Glasgow Centre for Population Health Tel: 0141 330 2747 Email: [email protected] Web: www.gcph.co.uk Twitter: @theGCPH 2 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 2 Contact .................................................................................................................................................... 2 Summary ................................................................................................................................................ -

North West Leicestershire District Council

Coalville (Ward) Demographics – Population Age structure Ethnic group Marital status Country of birth Religion Housing – Average House Price Number of Houses Housing tenure Housing Type Council tax band Page 1 of 14 Crime – Burglary, Assault Criminal damage, Theft (vehicle) Fires attended Other – Occupation groups Economically active / inactive General Health Qualifications and students Indices of deprivation Sources - Page 2 of 14 Demographics – Population Total population (2001) North West Great Coalville Leicestershire Britain All People 4494 85503 57103923 Males 2182 42240 27758419 Females 2312 43263 29345504 % of District population 5.2% Coalville Ward makes up 5.2% of the population for North West Leicestershire. Age structure Coalville No of People People aged 0 - 4 284 People aged 5 - 7 171 People aged 8 - 9 118 People aged 10 - 14 291 People aged 15 57 People aged 16 - 17 109 People aged 18 - 19 103 People aged 20 - 24 242 People aged 25 - 29 349 People aged 30 - 44 1036 People aged 45 - 59 743 People aged 60 - 64 201 People aged 65 - 74 374 People aged 75 - 84 267 People aged 85 - 89 93 People aged 90 & over 58 The table above shows the break down of the population in Coalville by age groups. Page 3 of 14 Age structure – The graph below looks at the age structure as a % and compares Coalville with that of North West Leicestershire. 25 23.04 23.02 21.21 20 Coalville Nortn West Leicestershire 16.53 15 10 8.39 8.32 7.76 6.47 6.42 6.32 5.99 5.89 5.94 5.84 5.38 5.06 4.77 5 4.47 3.8 3.6 2.62 2.59 2.42 2.29 2.29 2.07 1.95 1.27 1.29 1.24 1.22 0.51 0 0 - 4 5 - 7 8 - 9 10 - 14 15 16 - 17 18 - 19 20 - 24 25 - 29 30 - 44 45 - 59 60 - 64 65 - 74 75 - 84 85 - 89 90 & over The graph shows which age groups are most predominant. -

Ethnic Minorities in the Hospitality Sector Comparing the Experiences of Hospitality Workers from Different Ethnic Backgrounds

BRIEFING Ethnic minorities in the hospitality sector Comparing the experiences of hospitality workers from different ethnic backgrounds Sharon Mai & Nye Cominetti December 2020 resolutionfoundation.org @resfoundation Ethnic minorities in the hospitality sector | 2 Comparing the experiences of hospitality workers from different ethnic backgrounds Introduction This briefing note examines the experiences of workers in the hospitality sector from different ethnic backgrounds, and has been produced for the organisation ‘BAME in Hospitality’.1 There is a broad body of evidence showing that ethnic minorities experience disadvantage and worse outcomes in the labour market compared to people from a White British background, both in terms of rates of participation, and experiences when in work.2 This briefing note looks for evidence of differences in outcomes within the hospitality sector specifically. We show that the characteristics (such as age, and educational attainment) and experiences (such as earnings and occupation level) of different ethnic groups within the hospitality workforce vary considerably. In general, we focus on describing the experiences of individual ethnic groups rather than the collective ‘Black and Minority Ethnic’ (BAME) group. However, we do draw comparisons between workers from a BAME background and workers from a White British background when it comes to pay. Although those two groups have very similar raw earnings (when looking at median hourly pay), after controlling for personal characteristics (age, level of educational attainment, occupation type, etc.), we find workers from BAME backgrounds have lower earnings. The briefing note proceeds as follows. In the remainder of this introductory section we provide a brief overview of the hospitality sector, and how it has been affected by the coronavirus crisis. -

Who Feels Scottish? National Identities and Ethnicity in Scotland

August 2014 DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Who feels Scottish? National identities and ethnicity in Scotland Summary • 83% of Scotland’s residents feel Scottish. • About 25% of Scotland’s residents born outside Scotland • 61% of Scotland’s residents identify as being of White do feel Scottish, and this is no less for those from South Scottish ethnicity and feel Scottish is their only national and East Asia, Africa and the Middle East, than it is for identity. A further 22% are from other ethnic groups and those born in England or other parts of Europe. About a feel they have a Scottish national identity, or are White third of Scotland’s residents born in North America, the Scottish whose Scottishness is combined with British or Old Commonwealth and Western Europe feel Scottish. other national identities. • The Polish ethnic group, who have recently had the • Catholics, Protestants and those of no religion share highest migration rates into Scotland, expressed most similar levels of commitment to a Scottish only national affiliation to a non-UK identity only (80%). identity, while two-thirds of Muslims in Scotland identify • For other groups, including Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, as Scottish or British. Africans, Indians and Chinese, British only was chosen • The ‘White: Other British’ are the largest ethnic minority in as frequently as Scottish only. This perhaps reflects the Scotland, and the ethnic group least likely to feel Scottish emphasis on Britishness in citizenship regulations, and national identity (11% feel Scottish, with or without other was also found in England where minorities identified identities). -

Ethnic Inequalities in Manchester a Need for Local Partnerships and Solutions

Intelligence for a multi-ethnic Britain January 2017 Ethnic Inequalities in Manchester A need for local partnerships and solutions Summary This Briefing draws on data from the 2001 and 2011 Measuring Local Ethnic Inequalities Censuses and workshop discussions of academic researchers, Inequality for ethnic minorities in relation to the White community representatives and service providers, to identify British in education, employment, health and housing patterns and drivers of ethnic inequalities in Manchester, and has been calculated for districts in England and Wales potential solutions. The main findings are: using data from the 2001 and 2011 England and Wales • Manchester performs better than England and Wales in Census. Ethnic inequality is calculated as the absolute terms of ethnic inequalities in education, housing and difference in the proportion of the White British group health but worse on employment. and a particular ethnic minority group who experience disadvantage on key social indicators. The indicators of • There is considerable variation in ethnic inequalities inequality are: percent aged 16-24 with no qualifications between ethnic groups and across districts of Greater (Education); percent aged 25 and over who are Manchester. unemployed (Employment); percent with a limiting long • Employment inequality is particularly marked for the term illness (LLTI indirectly age standardized) (Health); Black African, Black Caribbean and Bangladeshi groups percent living with an occupancy rating of -1 or below, in Manchester. indicating overcrowding (Housing). A negative value indicates inequality (disadvantage) for the minority group. • Housing inequality is severe in Manchester and has Inequality was calculated for nine ethnic minority groups: worsened over the 2000s. White Irish, White Other, Mixed, Indian, Pakistani, • Minority advantage and reduction of inequalities in Bangladeshi, Chinese, Black African, Black Caribbean. -

Changing English Perceptions of the Irish from the 1820S Through the 1860S

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 From Peasant to Pariah: Changing English Perceptions of the Irish from the 1820s Through the 1860s Traci J. Scully West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Scully, Traci J., "From Peasant to Pariah: Changing English Perceptions of the Irish from the 1820s Through the 1860s" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3462. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3462 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Peasant to Pariah: Changing English Perceptions of the Irish from the 1820s Through the 1860s Traci J. Scully Dissertation submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences At West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Joseph Hodge, Ph.D., Chair Katherine Aaslestad, Ph.D. Kate Staples, Ph.D. Lisa Weihman, Ph.D. Sandra den Otter, Ph.D. -

Life Expectancy of Different Ethnic Groups Using Death Records Linked to Population Census Data for 4.62 Million People in Scotl

JECH Online First, published on July 29, 2016 as 10.1136/jech-2016-207426 Short report J Epidemiol Community Health: first published as 10.1136/jech-2016-207426 on 29 July 2016. Downloaded from Life expectancy of different ethnic groups using death records linked to population census data for 4.62 million people in Scotland Laurence Gruer,1 Geneviève Cézard,1 Esta Clark,2 Anne Douglas,1 Markus Steiner,3 Andrew Millard,4 Duncan Buchanan,5 Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi,6 Aziz Sheikh,1 Raj Bhopal1 ▸ Additional material is ABSTRACT Wales, deriving the proportion of the population published online only. To view Background Few countries record the data needed in each of the three groups from the 2001 please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech- to estimate life expectancy by ethnic group. Such Census. They then created life tables modelling 2016-207426). information is helpful in assessing the extent of health the effect on mortality rates of increasing propor- inequality. tions of the population being Asian or Black, 1Usher Institute for Population Health Sciences and Method Life tables were created using 3 years of adjusting for the effect of area deprivation. Rees 7 Informatics, University of deaths (May 2001–April 2004) linked to Scottish 2001 et al drew on evidence of a relationship between Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK Census data for 4.62 million individuals with self- self-reported health and subsequent mortality. 2 Demographic Statistics, reported ethnicity. We created 8 ethnic groups based They estimated age-specific and sex-specific mor- National Records of Scotland, fi Edinburgh, UK on the census de nitions, each with at least 5000 tality rates for 16 ethnic groups using the 2001 3Department of Child Health, individuals and 40 deaths.