Overview and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to the Legislature: Indoor Air Pollution in California

California Environmental Protection Agency Air Resources Board Report to the California Legislature INDOOR AIR POLLUTION IN CALIFORNIA A report submitted by: California Air Resources Board July, 2005 Pursuant to Health and Safety Code § 39930 (Assembly Bill 1173, Keeley, 2002) Arnold Schwarzenegger Governor Indoor Air Pollution in California July, 2005 ii Indoor Air Pollution in California July, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared with the able and dedicated support from Jacqueline Cummins, Marisa Bolander, Jeania Delaney, Elizabeth Byers, and Heather Choi. We appreciate the valuable input received from the following groups: • Many government agency representatives who provided information and thoughtful comments on draft reports, especially Jed Waldman, Sandy McNeel, Janet Macher, Feng Tsai, and Elizabeth Katz, Department of Health Services; Richard Lam and Bob Blaisdell, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment; Deborah Gold and Bob Nakamura, Cal/OSHA; Bill Pennington and Bruce Maeda, California Energy Commission; Dana Papke and Kathy Frevert, California Integrated Waste Management Board; Randy Segawa, and Madeline Brattesani, Department of Pesticide Regulation; and many others. • Bill Fisk, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, for assistance in assessing the costs of indoor pollution. • Susan Lum, ARB, project website management, and Chris Jakober, for general technical assistance. • Stakeholders from the public and private sectors, who attended the public workshops and shared their experiences and suggestions -

Community Outreach

Truckee Tahoe Airport District COMMUNITY OUTREACH Neighborhood Meetings October 2016 Draft Acknowledgements We wish to thank our supportive community who provided their insight and thoughtful feedback. TRUCKEE TAHOE AIRPORT DISTRICT BOARD AIRPORT COMMUNITY ADVISORY TEAM Lisa Wallace, President Kathryn Rohlf, Community Member/Chair James W. Morrison, Vice President Joe Polverari, Pilot Member/Vice Chair Mary Hetherington Christopher Gage, Pilot Member John B. Jones, Jr. Leigh Golden, Pilot Member J. Thomas Van Berkem Kent Hoopingarner, Community Member/Treasurer Lisa Krueger, Community Member AIRPORT STAFF Kevin Smith, General Manager BRIDGENET INTERNATIONAL Hardy Bullock, Director of Aviation Cindy Gibbs, Airspace Study Project Manager and Community Services Marc R. Lamb, Aviation and FRESHTRACKS COMMUNICATIONS Community Services Manager Seana Doherty, Owner/Founder Michael Cooke, Aviation and Phebe Bell, Facilitator Community Services Manager Amanda Wiebush, Associate Jill McClendon, Aviation and Community Greyson Howard,Mead &Associate Hunt, Inc. M & H Architecture, Inc. Services Program Coordinator 133 Aviation Boulevard, Suite 100 Lauren C. Tapia, District Clerk MEAD & HUNT,Santa INC. Rosa, California 95403 Mitchell Hooper,707-526-5010 West Coast Aviation meadhunt.com Planning Manager Brad Musinski, Aviation Planner Maranda Thompson, Aviation Planner TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND PROGRAM DESIGN .............................................. 1 2 NEIGHBORHOOD FEEDBACK ..................................................................... 5 APPENDICES A. Meeting Materials B. Public Comments C. Advertising and Marketing Efforts Introduction and ProgramMead & Hunt, Inc. Design M & H Architecture, Inc. 133 Aviation Boulevard, Suite 100 Santa Rosa, California 95403 707-526-5010 meadhunt.com INTRODUCTION Purpose The Truckee Tahoe Airport District (TTAD) understands that community input is incredibly valuable in developing good policies and making sound decisions about Truckee Tahoe Airport (TRK). -

Southwest Airlines 1996 Annual Report

1996 Annual Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Consolidated Highlights 2 Introduction 3 Letter to Shareholders 4 People and Planes 6 Southwest Spirit 8 THE Low Fare Airline 10 Productivity 12 Ontime Performance 14 Customer Satisfaction 16 Mintenance and Safety 18 What’s Next? 20 Financial Review 22 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 22 Consolidated Financial Statements 31 Report of Independent Auditors 49 Quarterly Financial Data 50 Common Stock Price Ranges and Dividends 50 Corporate Data 51 Directors and Officers 52 Ten Year Summary 55 CONSOLIDATED HIGHLIGHTS (DOLLARS IN THOUSANDS PERCENT EXCEPT PER SHARE AMOUNTS) 1996 1995 CHANGE Operating revenues $3,406,170 $2,872,751 18.6 Operating expenses $3,055,335 $2,559,220 19.4 Operating income $350,835 $313,531 11.9 Operating margin 10.3% 10.9% (0.6)pts. Net income $207,337 $182,626 13.5 Net margin 6.1% 6.4% (0.3)pts. Net income per common and common equivalent share $1.37 $1.23 11.4 Stockholders’ equity $1,648,312 $1,427,318 15.5 Return on average stockholders’ equity 13.5% 13.7% (0.2)pts. Debt as a percentage of invested capital 28.3% 31.7% (3.4)pts. Stockholders’ equity per common share outstanding $11.36 $9.91 14.6 Revenue passengers carried 49,621,504 44,785,573 10.8 Revenue passenger miles (RPMs)(000s) 27,083,483 23,327,804 16.1 Available seat miles (ASMs)(000s) 40,727,495 36,180,001 12.6 Passenger load factor 66.5% 64.5% 2.0 pts. Passenger revenue yield per RPM 12.07¢ 11.83¢ 2.0 Operating revenue yield per ASM 8.36¢ 7.94¢ 5.3 Operating expenses per ASM 7.50¢ 7.07¢ 6.1 Number of Employees at yearend 22,944 19,933 15.1 NET INCOME (in millions) $207 $179 $183 250 $154 200 $97 150 100 50 0 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 2 NET INCOME PER SHARE $1.37 $1.22 $1.23 1.40 $1.05 1.20 1.00 $.68 0.80 0.60 0.40 0.20 0.00 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 SOUTHWEST AIRLINES CO. -

Airline Competition Plan Final Report

Final Report Airline Competition Plan Philadelphia International Airport Prepared for Federal Aviation Administration in compliance with requirements of AIR21 Prepared by City of Philadelphia Division of Aviation Philadelphia, Pennsylvania August 31, 2000 Final Report Airline Competition Plan Philadelphia International Airport Prepared for Federal Aviation Administration in compliance with requirements of AIR21 Prepared by City of Philadelphia Division of Aviation Philadelphia, Pennsylvania August 31, 2000 SUMMARY S-1 Summary AIRLINE COMPETITION PLAN Philadelphia International Airport The City of Philadelphia, owner and operator of Philadelphia International Airport, is required to submit annually to the Federal Aviation Administration an airline competition plan. The City’s plan for 2000, as documented in the accompanying report, provides information regarding the availability of passenger terminal facilities, the use of passenger facility charge (PFC) revenues to fund terminal facilities, airline leasing arrangements, patterns of airline service, and average airfares for passengers originating their journeys at the Airport. The plan also sets forth the City’s current and planned initiatives to encourage competitive airline service at the Airport, construct terminal facilities needed to accommodate additional airline service, and ensure that access is provided to airlines wishing to serve the Airport on fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory terms. These initiatives are summarized in the following paragraphs. Encourage New Airline Service Airlines that have recently started scheduled domestic service at Philadelphia International Airport include AirTran Airways, America West Airlines, American Trans Air, Midway Airlines, Midwest Express Airlines, and National Airlines. Airlines that have recently started scheduled international service at the Airport include Air France and Lufthansa. The City intends to continue its programs to encourage airlines to begin or increase service at the Airport. -

TWA's Caribbean Flights Caribbean Cure for The

VOLUME 48 NUMBER 9 MAY 6, 1985 Caribbean . TWA's Caribbean Flights Cure for The Doldrums TWA will fly to the Caribbean this fall, President Ed Meyer announced. The air line willserve nine Caribbean destinations from New York starting November 15; at the same time, it will inaugurate non-stop service between St. Louis and SanJuan. Islands to be served are St. Thomas, the Bahamas, St. Maarten, St. Croix, Antigua, Martinique, Guadeloupe and Puerto Rico. For more than a decade TWA has con sistently been the leading airline across . the North Atlantic in terms of passengers carried. With the addition of the Caribbean routes, TWA willadd an important North South dimension to its internationalserv ices, Mr. Meyer said. "We expect that strong winter loads to Caribbean vacation destinations will help TWA counterbalance relatively light transatlantic traffic at that time of year, . and vice versa," he explained. "Travelers willbenefit from TWA's premiere experi ence in international operations and its reputation for excellent service," he added. Mr. Meyer emphasized TWA's leader ship as the largest tour operator across the Atlantic, and pointed to the airline's feeder network at both Kennedy and St. Louis: "Passengers from the west and midwest caneasily connect into these ma- (topage4) Freeport � 1st Quarter: Nassau SAN JUAN A Bit Better St. Thomas With the publication of TWA's first-quar St. Croix ter financial results,· the perennial ques tion recurs: "With load factors like that, how could we lose so much money?" Martinique As always, the answer isn't simple. First the numbers, then the words. -

AWA AR Editoral

AMERICA WEST HOLDINGS CORPORATION Annual Report 2002 AMERICA WEST HOLDINGS CORPORATION America West Holdings Corporation is an aviation and travel services company. Wholly owned subsidiary, America West Airlines, is the nation’s eighth largest carrier serving 93 destinations in the U.S., Canada and Mexico. The Leisure Company, also a wholly owned subsidiary, is one of the nation’s largest tour packagers. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chairman’s Message to Shareholders 3 20 Years of Pride 11 Board of Directors 12 Corporate Officers 13 Financial Review 15 Selected Consolidated Financial Data The selected consolidated data presented below under the captions “Consolidated Statements of Operations Data” and “Consolidated Balance Sheet Data” as of and for the years ended December 31, 2002, 2001, 2000, 1999 and 1998 are derived from the audited consolidated financial statements of Holdings. The selected consolidated data should be read in conjunction with the consolidated financial statements for the respective periods, the related notes and the related reports of independent accountants. Year Ended December 31, (in thousands except per share amounts) 2002 2001(a) 2000 1999 1998 (as restated) Consolidated statements of operations data: Operating revenues $ 2,047,116 $ 2,065,913 $ 2,344,354 $ 2,210,884 $ 2,023,284 Operating expenses (b) 2,207,196 2,483,784 2,356,991 2,006,333 1,814,221 Operating income (loss) (160,080) (417,871) (12,637) 204,551 209,063 Income (loss) before income taxes and cumulative effect of change in accounting principle (c) (214,757) -

United States Court of Appeals for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

USCA Case #11-1018 Document #1351383 Filed: 01/06/2012 Page 1 of 12 United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT Argued November 8, 2011 Decided January 6, 2012 No. 11-1018 REPUBLIC AIRLINE INC., PETITIONER v. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, RESPONDENT On Petition for Review of an Order of the Department of Transportation Christopher T. Handman argued the cause for the petitioner. Robert E. Cohn, Patrick R. Rizzi and Dominic F. Perella were on brief. Timothy H. Goodman, Senior Trial Attorney, United States Department of Transportation, argued the cause for the respondent. Robert B. Nicholson and Finnuala K. Tessier, Attorneys, United States Department of Justice, Paul M. Geier, Assistant General Counsel for Litigation, and Peter J. Plocki, Deputy Assistant General Counsel for Litigation, were on brief. Joy Park, Trial Attorney, United States Department of Transportation, entered an appearance. USCA Case #11-1018 Document #1351383 Filed: 01/06/2012 Page 2 of 12 2 Before: HENDERSON, Circuit Judge, and WILLIAMS and RANDOLPH, Senior Circuit Judges. Opinion for the Court filed by Circuit Judge HENDERSON. KAREN LECRAFT HENDERSON, Circuit Judge: Republic Airline Inc. (Republic) challenges an order of the Department of Transportation (DOT) withdrawing two Republic “slot exemptions” at Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (Reagan National) and reallocating those exemptions to Sun Country Airlines (Sun Country). In both an informal letter to Republic dated November 25, 2009 and its final order, DOT held that Republic’s parent company, Republic Airways Holdings, Inc. (Republic Holdings), engaged in an impermissible slot-exemption transfer with Midwest Airlines, Inc. (Midwest). -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

July/August 2000 Volume 26, No

Irfc/I0 vfa£ /1 \ 4* Limited Edition Collectables/Role Model Calendars at home or in the office - these photo montages make a statement about who we are and what we can be... 2000 1999 Cmdr. Patricia L. Beckman Willa Brown Marcia Buckingham Jerrie Cobb Lt. Col. Eileen M. Collins Amelia Earhart Wally Funk julie Mikula Maj. lacquelyn S. Parker Harriet Quimby Bobbi Trout Captain Emily Howell Warner Lt. Col. Betty Jane Williams, Ret. 2000 Barbara McConnell Barrett Colonel Eileen M. Collins Jacqueline "lackie" Cochran Vicky Doering Anne Morrow Lindbergh Elizabeth Matarese Col. Sally D. Woolfolk Murphy Terry London Rinehart Jacqueline L. “lacque" Smith Patty Wagstaff Florene Miller Watson Fay Cillis Wells While They Last! Ship to: QUANTITY Name _ Women in Aviation 1999 ($12.50 each) ___________ Address Women in Aviation 2000 $12.50 each) ___________ Tax (CA Residents add 8.25%) ___________ Shipping/Handling ($4 each) ___________ City ________________________________________________ T O TA L ___________ S ta te ___________________________________________ Zip Make Checks Payable to: Aviation Archives Phone _______________________________Email_______ 2464 El Camino Real, #99, Santa Clara, CA 95051 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS (ISSN 0273-608X) 99 NEWS INTERNATIONAL Published by THE NINETV-NINES* INC. International Organization of Women Pilots A Delaware Nonprofit Corporation Organized November 2, 1929 WOMEN PILOTS INTERNATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Box 965, 7100 Terminal Drive OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OFTHE NINETY-NINES® INC. Oklahoma City, -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Air Passenger Origin and Destination, Canada-United States Report

Catalogue no. 51-205-XIE Air Passenger Origin and Destination, Canada-United States Report 2005 How to obtain more information Specific inquiries about this product and related statistics or services should be directed to: Aviation Statistics Centre, Transportation Division, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0T6 (Telephone: 1-613-951-0068; Internet: [email protected]). For information on the wide range of data available from Statistics Canada, you can contact us by calling one of our toll-free numbers. You can also contact us by e-mail or by visiting our website at www.statcan.ca. National inquiries line 1-800-263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 Depository Services Program inquiries 1-800-700-1033 Fax line for Depository Services Program 1-800-889-9734 E-mail inquiries [email protected] Website www.statcan.ca Information to access the product This product, catalogue no. 51-205-XIE, is available for free in electronic format. To obtain a single issue, visit our website at www.statcan.ca and select Publications. Standards of service to the public Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, reliable and courteous manner. To this end, the Agency has developed standards of service which its employees observe in serving its clients. To obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics Canada toll free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are also published on www.statcan.ca under About us > Providing services to Canadians. Statistics Canada Transportation Division Aviation Statistics Centre Air Passenger Origin and Destination, Canada-United States Report 2005 Published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada © Minister of Industry, 2007 All rights reserved. -

Traffic Report

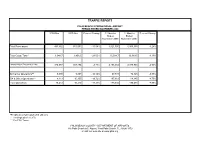

TRAFFIC REPORT PALM BEACH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PERIOD ENDED NOVEMBER 2008 2008/Nov 2007/Nov Percent Change 12 Months 12 Months Percent Change Ended Ended November 2008 November 2007 Total Passengers 493,852 561,053 -11.98% 6,521,590 6,955,356 -6.24% Total Cargo Tons * 1,048.7 1,456.6 -28.00% 15,584.7 16,083.5 -3.10% Landed Weight (Thousands of Lbs.) 326,077 357,284 -8.73% 4,106,354 4,370,930 -6.05% Air Carrier Operations** 5,099 5,857 -12.94% 67,831 72,125 -5.95% GA & Other Operations*** 8,313 10,355 -19.72% 107,861 118,145 -8.70% Total Operations 13,412 16,212 -17.27% 175,692 190,270 -7.66% H17 + H18 + H19 + H20 13,412.0000 16,212.0000 -17.27% 175,692.0000 190,270.0000 -7.66% * Freight plus mail reported in US tons. ** Landings plus takeoffs. *** Per FAA Tower. PALM BEACH COUNTY - DEPARTMENT OF AIRPORTS 846 Palm Beach Int'l. Airport, West Palm Beach, FL 33406-1470 or visit our web site at www.pbia.org TRAFFIC REPORT PALM BEACH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT AIRLINE PERCENTAGE OF MARKET November 2008 2008/Nov 12 Months Ended November 2008 Enplaned Market Share Enplaned Market Share Passengers Passengers Total Enplaned Passengers 246,559 100.00% 3,273,182 100.00% Delta Air Lines, Inc. 54,043 21.92% 676,064 20.65% JetBlue Airways 50,365 20.43% 597,897 18.27% US Airways, Inc. 36,864 14.95% 470,538 14.38% Continental Airlines, Inc.