A Work Project, Presented As Part of Requirements for the Award of a Master Degree in Finance from the NOVA - School of Business and Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AWA AR Editoral

AMERICA WEST HOLDINGS CORPORATION Annual Report 2002 AMERICA WEST HOLDINGS CORPORATION America West Holdings Corporation is an aviation and travel services company. Wholly owned subsidiary, America West Airlines, is the nation’s eighth largest carrier serving 93 destinations in the U.S., Canada and Mexico. The Leisure Company, also a wholly owned subsidiary, is one of the nation’s largest tour packagers. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chairman’s Message to Shareholders 3 20 Years of Pride 11 Board of Directors 12 Corporate Officers 13 Financial Review 15 Selected Consolidated Financial Data The selected consolidated data presented below under the captions “Consolidated Statements of Operations Data” and “Consolidated Balance Sheet Data” as of and for the years ended December 31, 2002, 2001, 2000, 1999 and 1998 are derived from the audited consolidated financial statements of Holdings. The selected consolidated data should be read in conjunction with the consolidated financial statements for the respective periods, the related notes and the related reports of independent accountants. Year Ended December 31, (in thousands except per share amounts) 2002 2001(a) 2000 1999 1998 (as restated) Consolidated statements of operations data: Operating revenues $ 2,047,116 $ 2,065,913 $ 2,344,354 $ 2,210,884 $ 2,023,284 Operating expenses (b) 2,207,196 2,483,784 2,356,991 2,006,333 1,814,221 Operating income (loss) (160,080) (417,871) (12,637) 204,551 209,063 Income (loss) before income taxes and cumulative effect of change in accounting principle (c) (214,757) -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

1 United States Securities and Exchange Commission

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q [X]Quarterly Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the Quarterly Period Ended September 30, 2002. [ ]Transition Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the Transition Period From to . Commission file number 1-2691. American Airlines, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 13-1502798 (State or other (I.R.S. Employer jurisdiction Identification No.) of incorporation or organization) 4333 Amon Carter Blvd. Fort Worth, Texas 76155 (Address of principal (Zip Code) executive offices) Registrant's telephone number, including area code (817) 963-1234 Not Applicable (Former name, former address and former fiscal year , if changed since last report) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes X No . Indicate the number of shares outstanding of each of the issuer's classes of common stock, as of the latest practicable date. Common Stock, $1 par value - 1,000 shares as of October 14, 2002. The registrant meets the conditions set forth in, and is filing this form with the reduced disclosure format prescribed by, General Instructions H(1)(a) and (b) of Form 10-Q. -

Overview and Trends

9310-01 Chapter 1 10/12/99 14:48 Page 15 1 M Overview and Trends The Transportation Research Board (TRB) study committee that pro- duced Winds of Change held its final meeting in the spring of 1991. The committee had reviewed the general experience of the U.S. airline in- dustry during the more than a dozen years since legislation ended gov- ernment economic regulation of entry, pricing, and ticket distribution in the domestic market.1 The committee examined issues ranging from passenger fares and service in small communities to aviation safety and the federal government’s performance in accommodating the escalating demands on air traffic control. At the time, it was still being debated whether airline deregulation was favorable to consumers. Once viewed as contrary to the public interest,2 the vigorous airline competition 1 The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 was preceded by market-oriented administra- tive reforms adopted by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) beginning in 1975. 2 Congress adopted the public utility form of regulation for the airline industry when it created CAB, partly out of concern that the small scale of the industry and number of willing entrants would lead to excessive competition and capacity, ultimately having neg- ative effects on service and perhaps leading to monopolies and having adverse effects on consumers in the end (Levine 1965; Meyer et al. 1959). 15 9310-01 Chapter 1 10/12/99 14:48 Page 16 16 ENTRY AND COMPETITION IN THE U.S. AIRLINE INDUSTRY spurred by deregulation now is commonly credited with generating large and lasting public benefits. -

Aadvantage Platinum Status Puts You Miles Ahead

AAdvantage Platinum Status Puts You Miles Ahead We’re pleased to have you as an AAdvantage Platinum member and to welcome you into a very distinguished group of travelers. To recognize your loyalty to American Airlines, we invite you to enjoy the following AAdvantage Platinum member benefits through February 29, 2004. AAdvantage Platinum Hot Line Access For reservations, upgrade purchases and requests, seating preferences or to order a special meal, call 1-800-843-3000. If you are outside of the continental U.S., Canada, Puerto Rico or the U.S. Virgin Islands, contact your local American Airlines reservations office. 2 You can also use the Platinum Hot Line to access our AAdvantage Dial-In® system to claim awards, purchase electronic upgrades at a discount and get AAdvantage® program information, as well as your individual account activity. If you don’t already have a PIN, you can call the Platinum Hot Line. Admirals Club® Membership We are pleased to offer you membership in the Admirals Club at a special discounted price. For information about the Admirals Club and these special rates, please visit www.aa.com/admiralsclub, call 1-800-237-7971 (from the continental U.S., Canada or Puerto Rico) or stop by any Admirals Club location worldwide. Flight Bonuses As an AAdvantage Platinum member, you receive a 100% mileage bonus on the base or guaranteed minimum miles for flights on American Airlines, American Eagle, AmericanConnection and our airline participants1. Earned Threshold Upgrades We will credit your upgrade account with four 500-mile electronic upgrades for every 10,000 base miles you earn, including guaranteed minimum miles, when you purchase a ticket on eligible American Airlines, American Eagle, AmericanConnection and airline participant1 flights during your membership year. -

Special Rates for Your Group

Special rates for your group. Group travel discounts include: 5% off the lowest applicable fare For reservations, call 1-800-433-1790, and refer to the authorization number below: AN# A8799AQ Now Book your Discount Fares Directly Online To take advantage of a 5% discount on AA, American Eagle and AmericanConnections. It's simple! After you have selected your flight(s) under the "Enter Passenger Details" tab, go to the "AA.com Promotion Code" field and enter in your Authorization Code without the leading “A”. Go directly to www.aa.com to book your flights. Discount Fares are valid for travel on American Airlines, American Eagle®, AmericanConnection®, oneworld Alliance, and codeshare partners from anywhere to your meeting destination. Reservations and Ticketing For reservations and ticketing information, call AmericanAirlines Meeting Services Desk, or have your travel professional call 1-800-433-1790 from anywhere in the United States or Canada, seven days a week, from 6:00 a.m. to 12:00 midnight (Central Time), and reference the authorization number shown above. Reservations for the hearing and speech impaired are also available at 1-800-543-1586. There is a $20.00USD reservations service fee for tickets issued through AA reservations, and a $30.00USD ticketing fee for tickets issued at the airport. Frequent Flyer Miles Earn AAdvantage® miles for your trip. The AAdvantage program was the first airline frequent traveler program, and for more than 20 years has offered members the most innovative ways to earn travel awards. Enroll online at www.aa.com. *Seats are limited. American Airlines, American Eagle, AmericanConnection, American Airlines Group & Meeting Travel and AAdvantage are marks of American Airlines, Inc. -

Fly Quiet Program Chicago O’Hare International Airport

2nd Quarter 2016 Report Fly Quiet Program Chicago O’Hare International Airport Visit the O’Hare Noise Webpage on the Internet at www.flychicago.com/ORDNoise nd 2 Quarter 2016 Report Background On June 17, 1997, the City of Chicago announced that airlines operating at O’Hare International Airport had agreed to use designated noise abatement flight procedures in accordance with the Fly Quiet Program. The Fly Quiet Program was implemented in an effort to further reduce the impacts of aircraft noise on the surrounding neighborhoods. The Fly Quiet Program is a voluntary program that encourages pilots and air traffic controllers to use designated nighttime preferential runways and flight tracks developed by the Chicago Department of Aviation in cooperation with the O'Hare Noise Compatibility Commission, the airlines, and the air traffic controllers. These preferred routes direct aircraft over less-populated areas, such as forest preserves, highways, as well as commercial and industrial areas. As part of the Fly Quiet Program, the Chicago Department of Aviation prepares a Quarterly Fly Quiet Report. This report is shared with Chicago Department of Aviation officials, the O'Hare Noise Compatibility Commission, the airlines, and the general public. The Fly Quiet Report contains detailed information regarding nighttime runway use, flight operations, flight tracks, and noise complaints and 24-hour tracking of ground run-ups. The data presented in this report is compiled from the Airport Noise Management System (ANMS) and airport operation logs. Operations O’Hare has seven runways that are all utilized at different times depending on a number of conditions including weather, airfield pavement and construction activities and air traffic demand. -

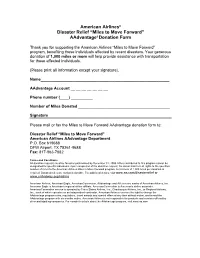

“Miles to Move Forward” Aadvantage® Donation Form

® American Airlines Disaster Relief “Miles to Move Forward” ® AAdvantage Donation Form Thank you for supporting the American Airlines “Miles to Move Forward” program, benefiting those individuals affected by recent disasters. Your generous donation of 1,000 miles or more will help provide assistance with transportation for those affected individuals. (Please print all information except your signature). Name___________________________________________________________ AAdvantage Account __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Phone number (____) __________ Number of Miles Donated __________________________________________ Signature Please mail or fax the Miles to Move Forward AAdvantage donation form to: Disaster Relief “Miles to Move Forward” American Airlines AAdvantage Department P.O. Box 619688 DFW Airport, TX 75261-9688 Fax: 817-963-7882 Terms and Conditions All donation requests must be faxed or postmarked by December 31, 2005. Miles contributed to this program cannot be designated for specific individuals. Upon completion of the donation request, the donor transfers all rights to the specified number of miles to the American Airlines Miles to Move Forward program. A minimum of 1,000 miles per donation is required. Donated miles are not tax deductible. For additional details, visit www.aa.com/disasterrelief or www.unitedway.org/katrina American Airlines, American Eagle, AmericanConnection, AAdvantage and AA.com are marks of American Airlines, Inc. American Eagle is American's regional airline affiliate. AmericanConnection is American's airline associate. AmericanConnection service is operated by Trans States Airlines, Inc., Chautauqua Airlines, Inc., or Regional Airlines, Inc., each of which operates as an independent contractor. American Airlines reserves the right to change the AAdvantage program rules, regulations, travel awards and special offers at any time without notice, and to end the AAdvantage program with six months notice. -

Filed by AMR Corporation Commission File No. 1-8400 Pursuant To

Filed by AMR Corporation Commission File No. 1-8400 Pursuant to Rule 425 Under the Securities Act of 1933 And Deemed Filed Pursuant to Rule 14a-12 Under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Subject Company: US Airways Group, Inc. Commission File No. 001-8444 ANreriwva Alsm Aerrriicvaanls Adrerifv.i nCgreating a Premier Global Carrier MA ajorcinht 2m0e, r2g0e1r 3communication for employees of the new American AIsrsriuvea ls5 is Now a Joint Publication oInf bthoeth s pcoirimt opfa onuiers m. Gerogienrg a fso rtwhaer dn,e we A’llm seproictalignh At ifrelinaetusr,e tsh ea bteoaumt bso ftrho ma irAlinmeesr ictoa nh ealnpd e UveSr yAoinrwea gyes th aacvqeu caoinmted t owgiteht htheer tnoe mwa ckoem tphaisn wy eaenkdly e maechrg oetrh neer’ws sbleutsteinre asvsa ailanbdl ec utoltu arell .employees aWttheantd beedt ttehre w anyn tuoa kl icWko omffe onu irn f iArsvti awteioenk coofn cvoemnbtioinne din dNisatsrihbvuitllieo,n T tehnan. ,w with esroem ae g Aromuepr icoaf nth/UoSug Ahitrfwual yAsm eemricpalony epeilo btso nbdroinugg?h tL faloswt eTrhsu arsndda ay ewmarpmlo wyeeelcso fmroem t ob oetmhp aloirylineess (asth tohwen U aSt left) HAeirwara Yyse ,t aHbelea.r EYveeryone involved expressed the same sentiment: We’re glad to be together! AUnSt iCtruEsOt, DCooumgp Petaitrikoenr Paonldic yA,m aenrdic aCno nCsEuOm eTro Rmig Hhotsrt.o Hne trrea vaerele da tfoe wC ahpigitholilg Hhitlls t hfriosm T utheesidr ateys ttoim oountylin: e the benefits of a merger before the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on “T..o.Omu Hr omrteorng eorn w tihthe UfuSt uAreirw oaf ytsh ew inll ecwre Aatmee trhicea ne: w American Airlines, a global competitor worthy of bearing the name of our country as America’s flag carrier. -

United States Securities and Exchange Commission

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D. C. 20549 _____________ FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of earliest event reported: June 8, 2012 American Airlines, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 1-2691 13-1502798 _ (State of Incorporation) (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer Identification No.) 4333 Amon Carter Blvd. Fort Worth, Texas 76155 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (817) 963-1234 _ (Registrant's telephone number) (Former name or former address, if changed since last report.) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: [ ] Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) [ ] Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) [ ] Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) [ ] Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 8.01 Other Events AMR Corporation, the parent company of American Airlines, Inc., issued a press release on June 8, 2012 reporting May revenue and traffic results. The press release is attached as Exhibit 99.1. SIGNATURE Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned hereunto duly authorized. -

US Airways, Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) (Commission File No

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 or o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to US Airways Group, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) (Commission File No. 1-8444) Delaware 54-1194634 (State or other Jurisdiction of (IRS Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 111 West Rio Salado Parkway, Tempe, Arizona 85281 (Address of principal executive offices, including zip code) (480) 693-0800 (Registrants telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, $0.01 par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None US Airways, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) (Commission File No. 1-8442) Delaware 54-0218143 (State or other Jurisdiction of (IRS Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 111 West Rio Salado Parkway, Tempe, Arizona 85281 (Address of principal executive offices, including zip code) (480) 693-0800 (Registrants telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: None Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE Portions of the proxy statement related to US Airways Group, Inc.’s 2009 Annual Meeting of Stockholders, which proxy statement will be filed under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 within 120 days of the end of US Airways Group, Inc.’s fiscal year ended December 31, 2008, are incorporated by reference into Part III of this Annual Report on Form 10-K. -

AMERICA WEST HOLDINGS CORPORATION Building a Winning Airline by Taking Care of Our Customers

AMERICA WEST HOLDINGS CORPORATION Building a winning airline by taking care of our customers. Annual Report 2003 www.americawest.com SELECTED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL DATA The selected consolidated financial data presented below under the captions “Consolidated Statements of Operations Data” and “Consolidated Balance Sheet Data” as of and for the years ended December 31, 2003, 2002, 2001, 2000 and 1999 are derived from the audited consolidated financial statements of America West Holdings Corporation. The selected consolidated financial data should be read in conjunction with the consolidated financial statements for the respective periods, the related notes and the related reports of independent auditors. Year Ended December 31, 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 (in thousands except per share amounts) Consolidated statements of operations data: Operating revenues $2,254,497 $2,047,116 $2,065,913 $2,344,354 $2,210,884 Operating expenses (a) 2,221,616 2,207,196 2,483,784 2,356,991 2,006,333 Operating income (loss) 32,881 (160,080) (417,871) (12,637) 204,551 Income (loss) before income taxes and cumulative effect of change in accounting principle (b) 57,534 (214,757) (324,387) 24,743 206,150 Income taxes (benefit) 114 (35,071) (74,536) 17,064 86,761 Income (loss) before cumulative effect of change in accounting principle 57,420 (179,686) (249,851) 7,679 119,389 Net income (loss) 57,420 (387,909) (249,851) 7,679 119,389 Earnings (loss) per share before cumulative effect of change in accounting principle: Basic 1.66 (5.33) (7.42) 0.22 3.17 Diluted 1.29