Aberystwyth University Journeys to the Limits of First-Hand Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Abgeordneten Der Bundes

Die Wahlkreisbüros der LINKEN in Nordrhein-Westfalen Die BürgerInnenbüro Ingrid Remmers Wahlkreisbüro Kathrin Vogler Wahlkreisbüro Kathrin Vogler Abgeordnetenbüro Inge Höger Abgeordneten Bismarckstr. 65, 45881 Gelsenkirchen Eper Str. 10, 48599 Gronau Rheiner Str. 39, 48282 Emsdetten Radewiger Str. 10, 32052 Herford Telefon (02 09) 38 65 19 90 Telefon (0 25 62) 7 18 59 80 Telefon (0 25 72) 9 60 77 60 Telefon (0 52 21) 1 74 90 71 der Bundes- Telefax (02 09) 38 65 06 09 Telefax (0 25 62) 7 18 59 81 Telefax (0 25 72) 9 60 67 65 Telefax (0 52 21) 1 74 90 73 Mail [email protected] Mail kathrin.vogler.wk.05@ Mail [email protected] Mail [email protected] wk.bundestag.de tagsfraktion Wahlkreisbüro Niema Movassat August-Bebel-Str. 126, 33603 Bielefeld DIE LINKE Elsässerstr. 19, 46045 Oberhausen Telefon: (05 21) 5 20 29 02 Telefon (02 08) 69 69 15 37 Telefax: (05 21) 5 20 29 03 Telefax (02 08) 69 69 15 39 Mail: [email protected] Nordrhein- Mail [email protected] Westfalen Wilhelm-Lantermann-Str. 55, Wahlkreisbüro Ulla Jelpke/ 46535 Dinslaken Linkes Zentrum Telefon (0 20 64) 4 81 54 06 Achtermannstr. 19, 48143 Münster Telefax (0 20 64) 4 81 55 42 Telefon (02 51) 4 90 92 46 Mail [email protected] Telefax (02 51) 4 90 92 92 Mail [email protected] Wahlkreisbüro Ulla Lötzer Severinstr. 1, 45127 Essen BürgerInnenbüro Ingrid Remmers (02 01) 49 02 14 51 Telefon Klosterstr. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 228. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 7. Mai 2021 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 1 Änderungsantrag der Abgeordneten Christian Kühn (Tübingen), Daniela Wagner, Britta Haßelmann, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN zu der zweiten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Drs. 19/24838, 19/26023, 19/29396 und 19/29409 Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Mobilisierung von Bauland (Baulandmobilisierungsgesetz) Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 611 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 98 Ja-Stimmen: 114 Nein-Stimmen: 431 Enthaltungen: 66 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 07.05.2021 Beginn: 12:25 Ende: 12:57 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Dr. Michael von Abercron X Stephan Albani X Norbert Maria Altenkamp X Peter Altmaier X Philipp Amthor X Artur Auernhammer X Peter Aumer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. André Berghegger X Melanie Bernstein X Christoph Bernstiel X Peter Beyer X Marc Biadacz X Steffen Bilger X Peter Bleser X Norbert Brackmann X Michael Brand (Fulda) X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Dr. Helge Braun X Silvia Breher X Sebastian Brehm X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Dr. Carsten Brodesser X Gitta Connemann X Astrid Damerow X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Thomas Erndl X Dr. Dr. h. c. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Enak Ferlemann X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Thorsten Frei X Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich (Hof) X Maika Friemann-Jennert X Michael Frieser X Hans-Joachim Fuchtel X Ingo Gädechens X Dr. -

Artikel Muster

VPT INFORMIERT Personal und Strukturen des Ausschusses für Gesundheit in der 18. Wahlperiode des Deutschen Bundestages – Vorsitz, Obleute, Berichterstatter und Sekretariat Unter Leitung des Bundestagsvizepräsidenten Johanes Singhammer (CSU) hat schlussempfehlungen an den Bundestag ̈ ̈ sich am 15. Januar 2014 der Ausschuss für Gesundheit konstituiert. Zum Vor- durfen sich nur auf die ihnen uberwiesenen Vorlagen oder mit diesen in unmittelbarem sitzenden wurde der 53-jährige promovierte Jurist Edgar Franke (SPD) bestimmt, Sachzusammenhang stehenden Fragen be- der damit die Nachfolge von Dr. Carola Reimann (SPD) antrat, die dem Ausschuss ziehen. Dies bedeutet also, dass den Aus- ̈ nicht mehr angehört und in den Vorstand der SPD-Bundestagsfraktion berufen schussen kein Initiativrecht im Plenum zu- kommt. Zu ihren Befugnissen zählt auch das wurde. Zitierrecht, wonach der Ausschuss die An- wesenheit eines Mitgliedes der Bundesre- Franke ist Rektor und Professor an der Hoch- sind bereits im 14. Jahrhundert„Standing gierung verlangen kann. Auch der Gesund- schule der Gesetzlichen Unfallversicherung Committees“ nachgewiesen. In Deutschland heitsausschuss macht von diesem Recht der in Bad Hersfeld und Mitherausgeber eines sahen Landesverfassungen des 19. Jahr- Herbeirufung aber nur selten Gebrauch, weil Lehr- und Praxiskommentars zum Siebten hunderts Ausschüsse vor. So wurden nach eine Bundesregierung um störungsfreie Buch Sozialgesetzbuch – Gesetzliche Un- einer Geschäftsordnung des Preußischen Kommunikationsflüsse zu den Ausschüssen fallversicherung. -

Kleine Anfrage Der Abgeordneten Andrej Hunko, Jan Korte, Ulla Jelpke, Dr

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 17/8145 17. Wahlperiode 13. 12. 2011 Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Andrej Hunko, Jan Korte, Ulla Jelpke, Dr. Petra Sitte, Frank Tempel, Alexander Ulrich, Kathrin Vogler, Halina Wawzyniak und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. Polizeiliche Soft- und Hardware bei den EU-Agenturen Seit Jahren rüsten auch polizeiliche EU-Agenturen ihr digitales Arsenal auf. Eu- ropol (Europäisches Polizeiamt) will zum „weltweit herausragenden Zentrum der Weltklasse“ (world-class centre of excellence) werden, was sich vor allem auf den IT-Bereich bezieht (www.europol.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/ anniversary_publication.pdf). Zentraler Bestandteil von Europol sind die um- fangreichen Datenbanken, deren Einrichtung im Europol-Übereinkommen fest- gelegt ist. Das „automatisierte System“ besteht aus drei Säulen, dem Informa- tionssystem, den Analysedateien und einem Indexsystem. Etliche EU-weite Abkommen erweitern die Zugriffsmöglichkeiten der Behörde. Europol selbst bezeichnet sich als „Information-Broker“ und sieht sich dem Grundsatz eines „proaktiven Handelns“. Mit dem deutschen Jürgen Storbeck als ersten amtieren- den Direktor 1999 und seinem Nachfolger Max-Peter Ratzel, vorher Abteilungs- präsident des Bundeskriminalamts (BKA), konnte Deutschland bis zum Antritt des britischen Rob Wainwright 2009 sein Gewicht in der Organisation ausbauen. Max-Peter Ratzel hatte im Oktober 2007 die neue „Strategy for Europol“ vorge- stellt. Durch die Ausweitung analytischer Kapazitäten sollte die Behörde zum Pionier des „Wandels, Identifizierung und Antwort auf neue Bedrohungen und der Entwicklung neuer Technik“ werden. Auch bei Europol kommt Software zur Vorgangsverwaltung, zu Ermittlungs- oder Analysezwecken oder zum Data-Mi- ning zur Anwendung. Nicht nur der Abgleich mehrerer Datensätze ist dabei pro- blematisch und kann als „Profiling“ bezeichnet werden. Die Software kann zudem mit „Zusatzapplikationen“ oder „Modulen“ erweitert werden, um weitere Daten- banken oder das Internet über Schnittstellen einzubinden. -

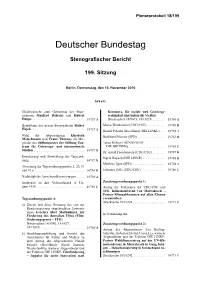

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a) -

Parlamentsmaterialien Beim DIP (PDF, 38KB

DIP21 Extrakt Deutscher Bundestag Diese Seite ist ein Auszug aus DIP, dem Dokumentations- und Informationssystem für Parlamentarische Vorgänge , das vom Deutschen Bundestag und vom Bundesrat gemeinsam betrieben wird. Mit DIP können Sie umfassende Recherchen zu den parlamentarischen Beratungen in beiden Häusern durchführen (ggf. oben klicken). Basisinformationen über den Vorgang [ID: 18-68571] Version für Lesezeichen / zum Verlinken 18. Wahlperiode Vorgangstyp: Gesetzgebung Gesetz zur Bekämpfung von Korruption im Gesundheitswesen Initiative: Bundesregierung Aktueller Stand: Verkündet GESTA-Ordnungsnummer: C080 Zustimmungsbedürftigkeit: Nein , laut Gesetzentwurf (Drs 360/15) Nein , laut Verkündung (BGBl I) Wichtige Drucksachen: BR-Drs 360/15 (Gesetzentwurf) BT-Drs 18/6446 (Gesetzentwurf) BT-Drs 18/8106 (Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht) Plenum: 1. Durchgang: BR-PlPr 936 , S. 330C - 332A 1. Beratung: BT-PlPr 18/137 , S. 13477B - 13485C 2. Beratung: BT-PlPr 18/164 , S. 16154B - 16164B 3. Beratung: BT-PlPr 18/164 , S. 16164A 2. Durchgang: BR-PlPr 945 , S. 187C Verkündung: Gesetz vom 30.05.2016 - Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I 2016 Nr. 25 03.06.2016 S. 1254 Sachgebiete: Recht ; Gesundheit Inhalt Beseitigung der Regelungslücke betr. unlautere Beeinflussung bei Verordnungs-, Abgabe- oder Zuführungsentscheidungen in akademischen Heilberufen und in Gesundheitsfachberufen: Schaffung von neuen Straftatbeständen der Bestechung und Bestechlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen, Strafrahmen in besonders schwerem Fall, relative Antragspflicht, Aufhebung der Differenzierung -

Migration, Integration, Asylum

www.ssoar.info Migration, Integration, Asylum: Political Developments in Germany 2018 Grote, Janne; Lechner, Claudia; Graf, Johannes; Schührer, Susanne; Worbs, Susanne; Konar, Özlem; Kuntscher, Anja; Chwastek, Sandy Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Forschungsbericht / research report Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Grote, J., Lechner, C., Graf, J., Schührer, S., Worbs, S., Konar, Ö., ... Chwastek, S. (2019). Migration, Integration, Asylum: Political Developments in Germany 2018. (Annual Policy Report / Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ)). Nürnberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ); Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Nationale Kontaktstelle für das Europäische Migrationsnetzwerk (EMN). https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168- ssoar-68295-9 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. -

Deutscher Bundestag Beschlussempfehlung Und Bericht

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/1948 18. Wahlperiode 01.07.2014 Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Ausschusses für Wahlprüfung, Immunität und Geschäftsordnung (1. Ausschuss) zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Irene Mihalic, Dr. Konstantin von Notz, Luise Amtsberg, Volker Beck (Köln), Frank Tempel, Jan Korte, Ulla Jelpke, Martina Renner, Jan van Aken, Agnes Alpers, Kerstin Andreae, Annalena Baerbock, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, Marieluise Beck (Bremen), Herbert Behrens, Karin Binder, Matthias W. Birkwald, Heidrun Bluhm, Dr. Franziska Brantner, Agnieszka Brugger, Christine Buchholz, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Roland Claus, Sevim Da÷delen,Dr.DietherDehm,EkinDeligöz,KatMaDörner,KatharinaDröge, Harald Ebner, Klaus Ernst, Dr. Thomas Gambke, Matthias Gastel, Wolfgang Gehrcke, Kai Gehring, Katrin Göring-Eckardt, Diana Golze, Annette Groth, Dr. Gregor Gysi, Heike Hänsel, Dr. André Hahn, Anja Hajduk, Britta Haßelmann, Dr. Rosemarie Hein, Inge Höger, Bärbel Höhn, Dr. Anton Hofreiter, Andrej Hunko, Sigrid Hupach, Dieter Janecek, Susanna Karawanskij, Kerstin Kassner, Uwe Kekeritz, Katja Keul, Sven-Christian Kindler, Katja Kipping, Maria Klein-Schmeink, Tom Koenigs, Sylvia Kotting-Uhl, Jutta Krellmann, Oliver Krischer, Stephan Kühn (Dresden), Christian Kühn (Tübingen), Renate Künast, Katrin Kunert, Markus Kurth, Caren Lay, Monika Lazar, Sabine Leidig, Steffi Lemke, Ralph Lenkert, Michael Leutert, Stefan Liebich, Dr. Tobias Lindner, Dr. Gesine Lötzsch, Thomas Lutze, Nicole Maisch, Peter Meiwald, Cornelia Möhring, Niema Movassat, Beate Müller-Gemmeke, Özcan Mutlu, Thomas Nord, Omid Nouripour, Cem Özdemir, Friedrich Ostendorff, Petra Pau, Lisa Paus, Harald Petzold (Havelland), Richard Pitterle, Brigitte Pothmer, Tabea Rößner, Claudia Roth (Augsburg), Corinna Rüffer, Manuel Sarrazin, Elisabeth Scharfenberg, Ulle Schauws, Dr. Gerhard Schick, Michael Schlecht, Dr. Frithjof Schmidt, Kordula Schulz-Asche, Dr. Petra Sitte, Kersten Steinke, Dr. Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn, Hans-Christian Ströbele, Dr. -

Rekrutierung Minderjähriger Beenden

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/480 18. Wahlperiode 11.02.2014 Antrag der Abgeordneten Katrin Kunert, Diana Golze, Wolfgang Gehrcke, Jan van Aken, Christine Buchholz, Sevim Dağdelen, Dr. Diether Dehm, Annette Groth, Heike Hänsel, Dr. André Hahn, Dr. Rosemarie Hein, Inge Höger, Andrej Hunko, Ulla Jelpke, Michael Leutert, Stefan Liebich, Niema Movassat, Dr. Alexander Neu, Frank Tempel, Alexander Ulrich, Kathrin Vogler, Harald Weinberg, Katrin Werner und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. Rekrutierung von Minderjährigen für die Bundeswehr beenden - Fakultativproto- koll zur UN-Kinderrechtskonvention vollständig umsetzen Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Deutschland hat das Fakultativprotokoll zur UN-Kinderrechtskonvention betref- fend die Beteiligung von Kindern an bewaffneten Konflikten mit erarbeitet und am 13. Dezember 2004 ratifiziert. Zusätzlich hat die Bundesregierung im Rah- men der Mitgliedschaft Deutschlands im UN-Sicherheitsrat 2011/12 auch den Vorsitz der Arbeitsgruppe „Kinder in bewaffneten Konflikten“ übernommen. Die Vereinten Nationen (UN) gehen davon aus, dass gegenwärtig in mindestens 22 Staaten zirka 250 000 Kinder unter 18 Jahren für die aktive Teilnahme an militärischen Kampfhandlungen bzw. für unterstützende Tätigkeiten zwangsre- krutiert werden. Nach Auffassung und politischer Praxis einer deutlichen Staa- tenmehrheit muss deshalb als Konsequenz aus dem Fakultativprotokoll für den obligatorischen oder freiwilligen Militärdienst in den regulären Streitkräften die Volljährigkeitsgrenze von 18 Jahren strikt eingehalten werden. Deutschland gehört zu den wenigen Vertragsstaaten, die im eigenen Land von der Ausnahmeregelung des Fakultativprotokolls Gebrauch machen und minder- jährige Freiwillige für die nationalen Streitkräfte anwerben. In der Praxis betrifft dies freiwillige Wehrdienstleistende und Soldatinnen und Soldaten auf Zeit, die als 17-Jährige eine militärische Ausbildung bei der Bundeswehr beginnen. -

Plenarprotokoll 19/167

Plenarprotokoll 19/167 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 167. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 19. Juni 2020 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt 26: Zusatzpunkt 25: a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen der Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD eingebrachten Ent- CDU/CSU und SPD eingebrachten Entwurfs wurfs eines Zweiten Gesetzes zur Umset- eines Gesetzes über begleitende Maßnah- zung steuerlicher Hilfsmaßnahmen zur men zur Umsetzung des Konjunktur- und Bewältigung der Corona-Krise (Zweites Krisenbewältigungspakets Corona-Steuerhilfegesetz) Drucksache 19/20057 . 20873 D Drucksache 19/20058 . 20873 B in Verbindung mit b) Erste Beratung des von der Bundesregie- rung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Zwei- ten Gesetzes über die Feststellung eines Zusatzpunkt 26: Nachtrags zum Bundeshaushaltsplan Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und für das Haushaltsjahr 2020 (Zweites SPD: Beschluss des Bundestages gemäß Ar- Nachtragshaushaltsgesetz 2020) tikel 115 Absatz 2 Satz 6 und 7 des Grund- Drucksache 19/20000 . 20873 B gesetzes Drucksache 19/20128 . 20874 A c) Antrag der Abgeordneten Kay Gottschalk, Marc Bernhard, Jürgen Braun, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der AfD: in Verbindung mit Arbeitnehmer, Kleinunternehmer, Frei- berufler, Landwirte und Solo-Selbstän- Zusatzpunkt 27: dige aus der Corona-Steuerfalle befreien Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Dirk Spaniel, und gleichzeitig Bürokratie abbauen Wolfgang Wiehle, Leif-Erik Holm, weiterer Drucksache 19/20071 . 20873 C Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der AfD: d) Antrag der Abgeordneten Caren Lay, Deutscher Automobilindustrie zeitnah hel- Simone Barrientos, Dr. Gesine Lötzsch, fen, Bahnrettung statt Konzernrettung, Be- weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion richte des Bundesrechnungshofs auch in DIE LINKE: Clubs und Festivals über der Krise beachten und umsetzen die Corona-Krise retten Drucksache 19/20072 . -

Ordneten Bayram Wird Schriftlich Beantwortet. Vielen Dank

Deutscher Bundestag – 19. Wahlperiode – 16. Sitzung. Berlin, Mittwoch, den 28. Februar 2018 1341 (A) Vizepräsident Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich: Dr. Michael Meister, Parl. Staatssekretär beim Bun- (C) Dann ist auch das beantwortet. – Frage 32 der Abge- desminister der Finanzen: ordneten Bayram wird schriftlich beantwortet. Ja. Vielen Dank, Herr Staatssekretär. Vizepräsident Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich: Wir kommen zum Geschäftsbereich des Bundesminis- Eine Zusatzfrage des Kollegen Axel Fischer. teriums der Finanzen. Zur Beantwortung steht Staatsse- kretär Dr. Michael Meister zur Verfügung. Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) (CDU/CSU): Wir kommen zur Frage 33 des Kollegen Klaus-Peter Ich frage die geschäftsführende Bundesregierung, wie Willsch: sie die Refnanzierungsfähigkeit der Länder Irland, Por- Wie bewertet die Bundesregierung die Refnanzierungsfä- tugal, Italien und Spanien bewertet. higkeit Griechenlands nach Auslaufen des dritten Hilfspaketes im August dieses Jahres? Dr. Michael Meister, Parl. Staatssekretär beim Bun- Herr Staatssekretär, bitte schön. desminister der Finanzen: Wir gehen davon aus, dass sich die Situation aufgrund des Wachstums, sowohl in Irland wie auch in Spanien, Dr. Michael Meister, Parl. Staatssekretär beim Bun- desminister der Finanzen: für beide Länder deutlich verbessert hat. Herr Präsident! Lieber Kollege Willsch, die griechi- Was Spanien anbelangt, gab es in jüngerer Vergangen- sche Schuldenagentur konnte am 8. Februar dieses Jahres heit eine vorzeitige Rückzahlung in Richtung ESM. Das erstmals wieder seit 2010 eine Staatsanleihe mit sieben- zeigt, dass ofensichtlich auch die spanische Regierung jähriger Laufzeit am Finanzmarkt platzieren. Die Emis- davon ausgeht, sich vernünftig refnanzieren zu können. sion brachte 3 Milliarden Euro ein – bei einer Nachfrage Bei Irland ist seit Ende des Hilfsprogramms die Nach- am Markt in Höhe von 7 Milliarden Euro. -

Drucksache 18/1767

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/1767 18. Wahlperiode 17.06.2014 Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Jan van Aken, Christine Buchholz, Inge Höger, Heike Hänsel, Katrin Kunert, Stefan Liebich, Niema Movassat, Dr. Alexander S. Neu, Kathrin Vogler und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. Produktion und Verbreitung von Landminen und Verlegesysteme für diese Unter Landminen werden nicht nur Antipersonenminen, sondern auch Antifahr- zeugminen gefasst, die sich gegen Fahrzeuge aller Art richten. Antifahrzeugmi- nen reagieren z. B. auf Überfahren oder auf Motorwärme, Motorgeräusche oder Bodenerschütterung und werden so zur Auslösung gebracht. Die Ächtung von Antipersonenminen ist durch die Ottawa-Konvention fest- geschrieben, die den Einsatz, die Produktion, den Transfer und den Handel von Antipersonenminen verbietet. Die Konvention gilt für „Minen, die der Kon- struktion nach gegen Personen gerichtet sind […]. Minen, die nicht gegen Per- sonen sondern gegen Fahrzeuge gerichtet sind, fallen nicht unter das Verbot.“ (www.landmine.de/infos-ueber-minen-und-streumunition/welche-minen-sind- verboten.html). Für Antifahrzeugminen existiert eine solche Ächtung nicht. Diese Minen ge- fährden aber ebenfalls die Zivilbevölkerung, die in zivilen Fahrzeugen, wie Bus- sen, Lkw, landwirtschaftlichen Fahrzeugen, fahren bzw. transportiert werden. Zudem gibt es als Antifahrzeugminen definierte Minen, die auch von Personen ausgelöst werden können und damit wie Antipersonenminen wirken; je nach Bauart auch noch lange Zeit nach Verlegung der Minen. Deshalb kritisieren zivilgesellschaftliche Organisationen, wie z. B. die Internationale Kampagne für das Verbot von Landminen, schon lange, dass es unzureichend ist, die tech- nischen Eigenschaften oder Bestandteile einer Mine als Kriterium der Ächtung zu nehmen und fordern dagegen eine „effektorientierte Definition dieser Waffe“ (vgl. www.landmine.de). In dieser Kleinen Anfrage werden unter dem Begriff „Landmine“ alle Landmi- nentypen, wie Antipanzerminen, Antifahrzeugminen, Anti-Material-Submuni- tionsminen, intelligente Wirksysteme u.