Exchange Rate Unification: the Cuban Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meetings & Incentives

MOVES PEOPLE TO BUSINESS TRAVEL & MICE Nº 37 EDICIÓN ESPECIAL FERIAS 2016-2017 / SPECIAL EDITION SHOWS 2016-2017 5,80 € BUSCANDO América Meetings & Incentives Edición bilingüe Bilingual edition 8 PRESENTACIÓN INTRODUCTION Buscando América. Un Nuevo Searching for America. A New Mundo de oportunidades 8 World of Opportunities 9 NORTE Y CENTRO NORTH AND CENTRAL Belice 16 Belize 16 Costa Rica 18 Costa Rica 19 El Salvador 22 El Salvador 22 14 Guatemala 24 Guatemala 24 Honduras 28 Honduras 28 México 30 Mexico 30 Nicaragua 36 Nicaragua 36 Panamá 40 Panama 40 CARIBE CARIBEAN Cuba 48 Cuba 48 Jamaica 52 Jamaica 52 Puerto Rico 54 Puerto Rico 54 46 República Dominicana 58 Dominican Republic 58 SUDAMÉRICA SOUTH AMERICA Argentina 64 Argentina 64 Bolivia 70 Bolivia 70 Brasil 72 Brazil 72 62 Chile 78 Chile 78 Colombia 82 Colombia 82 Ecuador 88 Ecuador 88 Paraguay 92 Paraguay 92 Perú 94 Peru 94 Uruguay 98 Uruguay 99 Venezuela 102 Venezuela 102 104 TURISMO RESPONSABLE SUSTAINABLE TOURISM 106 CHECK OUT Un subcontinente cada vez más An increasingly consolidated consolidado en el segmento MICE continent in the MICE segment Txema Txuglà Txema Txuglà MEET IN EDICIÓN ESPECIAL FERIAS 2016-2017 / SPECIAL EDITION SHOWS 2016-2017 EDITORIAL Natalia Ros EDITORA Fernando Sagaseta DIRECTOR Te busco y sí te I search for you encuentro and I find you «Te estoy buscando, América… Te busco y no te encuentro», “ I am searching for you America… I am searching for you but cantaba en los 80 el panameño Rubén Blades, por más señas I can’t find you ”, sang the Panamanian Rubén Blades in the ministro de Turismo de su país entre 2004 y 2009. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Culture Box of Cuba

CUBA CONTENIDO CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................3 Introduction .................................6 Items .............................................8 More Information ........................89 Contents Checklist ......................108 Evaluation.....................................110 AGRADECIMIENTOS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributors The Culture Box program was created by the University of New Mexico’s Latin American and Iberian Institute (LAII), with support provided by the LAII’s Title VI National Resource Center grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Contributing authors include Latin Americanist graduate students Adam Flores, Charla Henley, Jennie Grebb, Sarah Leister, Neoshia Roemer, Jacob Sandler, Kalyn Finnell, Lorraine Archibald, Amanda Hooker, Teresa Drenten, Marty Smith, María José Ramos, and Kathryn Peters. LAII project assistant Katrina Dillon created all curriculum materials. Project management, document design, and editorial support were provided by LAII staff person Keira Philipp-Schnurer. Amanda Wolfe, Marie McGhee, and Scott Sandlin generously collected and donated materials to the Culture Box of Cuba. Sponsors All program materials are readily available to educators in New Mexico courtesy of a partnership between the LAII, Instituto Cervantes of Albuquerque, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and Spanish Resource Center of Albuquerque - who, together, oversee the lending process. To learn more about the sponsor organizations, see their respective websites: • Latin American & Iberian Institute at the -

When Racial Inequalities Return: Assessing the Restratification of Cuban Society 60 Years After Revolution

When Racial Inequalities Return: Assessing the Restratification of Cuban Society 60 Years After Revolution Katrin Hansing Bert Hoffmann ABSTRACT Few political transformations have attacked social inequalities more thoroughly than the 1959 Cuban Revolution. As the survey data in this article show, however, sixty years on, structural inequalities are returning that echo the prerevolutionary socioethnic hierarchies. While official Cuban statistics are mute about social differ- ences along racial lines, the authors were able to conduct a unique, nationwide survey with more than one thousand respondents that shows the contrary. Amid depressed wages in the state-run economy, access to hard currency has become key. However, racialized migration patterns of the past make for highly unequal access to family remittances, and the gradual opening of private business disfavors Afro- Cubans, due to their lack of access to prerevolutionary property and startup capital. Despite the political continuity of Communist Party rule, a restructuring of Cuban society with a profound racial bias is turning back one of the proudest achieve- ments of the revolution. Keywords: Cuba, social inequality, race, socialism, migration, remittances he 1959 Cuban Revolution radically broke with a past in which “class” tended Tto influence and overlap most aspects of social life, including “race,” gender, income, education, and territory. The “centralized, state-sponsored economy, which provided full employment and guaranteed modest income differences, was the great social elevator of the lower strata of society. As a result, by the 1980s Cuba had become one of the most egalitarian societies in the world” (Mesa-Lago and Pérez- López 2005, 71). Katrin Hansing is an associate professor of sociology and anthropology at Baruch College, City University of New York. -

Cuba! Identity Revealed Through Cultural Connections

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2016 Volume II: Literature and Identity Cuba! Identity Revealed through Cultural Connections Curriculum Unit 16.02.07 by Waltrina Dianne Kirkland-Mullins Introduction I am a New Haven, Connecticut Public School instructor who loves to travel abroad. I do so because it affords me the opportunity to connect with people from myriad cultures, providing insight into the lives, customs, and traditions of diverse populations within our global community. It too helps me have a better understanding of diverse groups of Americans whose families live beyond American shores, many with whom I interact right within my New Haven residential and school community. Equally important, getting to experience diverse cultures first-hand helps to dispel misconceptions and false identification regarding specific cultural groups. Last summer, I was honored to travel to Cuba as part of a team of college students, teaching professionals, and businesspersons who visited the country with Washington State’s Pinchot University. While there, I met and conversed with professors, educators, entrepreneurs, scientists, and everyday folk—gaining insight into Cuba and its people from their perspective. Through that interaction, I experienced that Cuba, like the U.S., is a diverse nation. Primarily comprised of descendants of the Taíno, the Ciboney, and Arawak (original inhabitants of the island), Africans, and Spaniards, the diversity is evident in the color spectrum of the population, ranging from deep, ebony-hues to sun-kissed tan and creamy vanilla tones. I too learned something deeper. One afternoon, my Pinchot roommate and I decided to venture out to visit Callejon de Hamel , a narrow thoroughfare laden with impressive Santeria murals, sculptures, and Yoruba images. -

Black Market Peso Exchange As a Mechanism to Place Substantial Amounts of Currency from U.S

United States Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network FinCEN Advisory Subject: This advisory is provided to alert banks and other depository institutions Colombian to a large-scale, complex money laundering system being used extensively by Black Market Colombian drug cartels to launder the proceeds of narcotics sales. This Peso Exchange system is affecting both U.S. financial depository institutions and many U.S. businesses. The information contained in this advisory is intended to help explain how this money laundering system works so that U.S. financial institutions and businesses can take steps to help law enforcement counter it. Overview Date: November Drug sales in the United States are estimated by the Office of National 1997 Drug Control Policy to generate $57.3 billion annually, and most of these transactions are in cash. Through concerted efforts by the Congress and the Executive branch, laws and regulatory actions have made the movement of this cash a significant problem for the drug cartels. America’s banks have effective systems to report large cash transactions and report suspicious or Advisory: unusual activity to appropriate authorities. As a result of these successes, the Issue 9 placement of large amounts of cash into U.S. financial institutions has created vulnerabilities for the drug organizations and cartels. Efforts to avoid report- ing requirements by structuring transactions at levels well below the $10,000 limit or camouflage the proceeds in otherwise legitimate activity are continu- ing. Drug cartels are also being forced to devise creative ways to smuggle the cash out of the country. This advisory discusses a primary money laundering system used by Colombian drug cartels. -

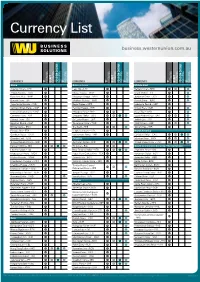

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Colombian Peso Forecast Special Edition Nov

Friday Nov. 4, 2016 Nov. 4, 2016 Mexican Peso Outlook Is Bleak With or Without Trump Buyside View By George Lei, Bloomberg First Word The peso may look historically very cheap, but weak fundamentals will probably prevent "We're increasingly much appreciation, regardless of who wins the U.S. election. concerned about the The embattled currency hit a three-week low Nov. 1 after a poll showed Republican difference between PDVSA candidate Donald Trump narrowly ahead a week before the vote. A Trump victory and Venezuela. There's a could further bruise the peso, but Hillary Clinton wouldn't do much to reverse 26 scenario where PDVSA percent undervaluation of the real effective exchange rate compared to the 20-year average. doesn't get paid as much as The combination of lower oil prices, falling domestic crude production, tepid economic Venezuela." growth and a rising debt-to-GDP ratio are key challenges Mexico must address, even if — Robert Koenigsberger, CIO at Gramercy a status quo in U.S. trade relations is preserved. Oil and related revenues contribute to Funds Management about one third of Mexico's budget and output is at a 32-year low. Economic growth is forecast at 2.07 percent in 2016 and 2.26 percent in 2017, according to a Nov. 1 central bank survey. This is lower than potential GDP growth, What to Watch generally considered at or slightly below 3 percent. To make matters worse, Central Banks Deputy Governor Manuel Sanchez said Oct. Nov. 9: Mexico's CPI 21 that the GDP outlook has downside risks and that the government must urgently Nov. -

The Wall Street Journal New York, New York 25 July 2021

U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, Inc. New York, New York Telephone (917) 453-6726 • E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.cubatrade.org • Twitter: @CubaCouncil Facebook: www.facebook.com/uscubatradeandeconomiccouncil LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/u-s--cuba-trade-and-economic-council-inc- The Wall Street Journal New York, New York 25 July 2021 Opinion The Americas The Root Causes of Cuban Poverty The only blockade is the one imposed by Havana. Regime elites oppose competition. A man is arrested during a demonstration against the government of Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canel in Havana, July 11. Photo: yamil lage/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images Cuba’s primal scream for liberty on July 11 has gone viral and exposed the grisly methods used by Cuba’s gestapo to keep the lid on dissent. But Cubans need outside help. They need the civilized world to come together and ostracize the barbarians in Havana. This requires U.S. leadership. Unfortunately, the Biden administration hasn’t seemed up to the task. Repression and propaganda are the only two things that Havana does well. U.S. intervention to protect against human-rights violations is not practical. But the Biden administration could launch a campaign to inform the public about the realities of Cuban communism. Vice President Kamala Harris might label it “the root causes” of Cuban poverty. Debunking the Marxist myth that sanctions impede Cuban development would be a good place to start. For decades, Cuba has blamed what it calls the U.S. “blockade” for island privation. Regime talking points have been repeated ad nauseam in U.S. -

Cuba's New Social Structure: Assessing the Re- Stratification of Cuban Society 60 Years After Revolution

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Hansing, Katrin; Hoffmann, Bert Working Paper Cuba's new social structure: Assessing the re- stratification of Cuban society 60 years after revolution GIGA Working Papers, No. 315 Provided in Cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Suggested Citation: Hansing, Katrin; Hoffmann, Bert (2019) : Cuba's new social structure: Assessing the re-stratification of Cuban society 60 years after revolution, GIGA Working Papers, No. 315, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193161 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Inclusion of a paper in the Working Papers series does not constitute publication and should limit in any other venue. -

The Modern History of Exchange Rate Arrangements

THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS Vol. CXIX February2004 Issue 1 THEMODERN HISTORY OFEXCHANGE RATE ARRANGEMENTS: AREINTERPRETATION* CARMEN M. REINHART AND KENNETH S. ROGOFF Wedevelopa novelsystem of reclassifyinghistorical exchange rate regimes. Onekey differencebetween our study andprevious classi cations is that we employmonthly data on market-determined parallel exchange rates going back to 1946for 153 countries. Our approachdiffers from the IMF of cial classi cation (whichwe show to be only a littlebetter than random); it also differs radically fromall previous attempts at historicalreclassi cation. Our classication points toa rethinkingof economicperformance under alternative exchange rate regimes. Indeed,the breakup of BrettonWoods had less impact on exchangerate regimes thanis popularly believed. I. INTRODUCTION Thispaper rewritesthe history of post-World WarII ex- changerate arrangements, based onan extensivenew monthly data setspanning across153 countriesfor 1946 –2001. Ourap- proachdiffers notonly from countries’ of cially declaredclassi - cations(which weshowto be only a littlebetter than random);it alsodiffers radically fromthe small numberof previous attempts at historicalreclassi cation. 1 *Theauthors wish to thank Alberto Alesina, Arminio Fraga, Amartya Lahiri, VincentReinhart, Andrew Rose,Miguel Savastano, participants at HarvardUni- versity’s Canada-US Economicand Monetary Integration Conference,Interna- tionalMonetary Fund-World Bank JointSeminar, National Bureau of Economic ResearchSummer Institute, New York University,Princeton -

Argentina's 2001 Economic and Financial Crisis: Lessons for Europe

Argentina’s 2001 economic and Financial Crisis: Lessons for europe Former Under Secretary of Finance and Chief Advisor to the Minister of the Miguel Kiguel Economy, Argentina; Former President, Banco Hipotecario; Director, Econviews; Professor, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella he 2001 Argentine economic and financial banks and international reserves—was not enough crisis has many parallels with the problems to cover the financial liabilities of the consolidated Tthat some European countries are facing to- financial system . This was a major source of vulner- day . Prior to the crisis, Argentina was suffering a ability, especially because there is ample evidence deep recession, large levels of debt, twin deficits in that an economy without a lender of last resort is the fiscal and current accounts, and the country inherently unstable and subject to bank runs . This had an overvalued currency but devaluation was is not a pressing issue in Europe, where the Euro- not an option . pean Central Bank can provide liquidity to banks . Argentina tried in vain to restore its competitive- The trigger for the crisis in Argentina was a run on ness through domestic deflation and improving the banking system as people realized that there its solvency by increasing its fiscal accounts in were not enough dollars in the system to cover all the midst of a recession . The country also tried to the deposits . As the run intensified, the Argentine avoid a default first by resorting to a large financial government was forced to introduce a so-called package from the multilateral institutions (the so “fence” to control the outflow of deposits .