Proceedingsofthe015177mbp.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portrayal of Family Ties in Ancient Sanskrit Plays: a Study

Volume II, Issue VIII, December 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 Portrayal of Family Ties in Ancient Sanskrit Plays: A Study Dr. C. S. Srinivas Assistant Professor of English Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Technology Hyderabad India Abstract The journey of the Indian dramatic art begins with classical Sanskrit drama. The works of the ancient dramatists Bhasa, Kalidasa, Bhavabhuti and others are the products of a vigorous creative energy as well as sustained technical excellence. Ancient Sanskrit dramatists addressed several issues in their plays relating to individual, family and society. All of them shared a common interest— familial and social stability for the collective good. Thus, family and society became their most favoured sites for weaving plots for their plays. Ancient Sanskrit dramatists with their constructive idealism always portrayed harmonious filial relationships in their plays by persistently picking stories from the two great epics Ramayana and Mahabharata and puranas. The paper examines a few well-known ancient Sanskrit plays and focuses on ancient Indian family life and also those essential human values which were thought necessary and instrumental in fostering harmonious filial relationships. Keywords: Family, Filial, Harmonious, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Sanskrit drama. _______________________________________________________________________ http://www.ijellh.com 224 Volume II, Issue VIII, December 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 The ideals of fatherhood and motherhood are cherished in Indian society since the dawn of human civilization. In Indian culture, the terms ‘father’ and ‘mother’ do not have a limited sense. ‘Father’ does not only mean the ‘male parent’ or the man who is the cause of one’s birth. In a broader sense, ‘father’ means any ‘elderly venerable man’. -

Prabuddha Bharata

2 THE ROAD TO WISDOM Swami Vivekananda on The Mechanics of Prana ll the automatic movements and all the Aconscious movements are the working of Prana through the nerves. It will be a very good thing to have control over the unconscious actions. Man is an infinite circle whose circumference is nowhere, but the centre is located in one spot; and God is an infinite circle whose circumference is nowhere, but whose centre is everywhere. man could refrain from doing evil. All the He works through all hands, sees through systems of ethics teach, ‘Do not steal!’ Very all eyes, walks on all feet, breathes through good; but why does a man steal? Because all all bodies, lives in all life, speaks through stealing, robbing, and other evil actions, as a every mouth, and thinks through every rule, have become automatic. The systematic brain. Man can become like God and robber, thief, liar, unjust man and woman, acquire control over the whole universe if are all these in spite of themselves! It is he multiplies infinitely his centre of self- really a tremendous psychological problem. consciousness. Consciousness, therefore, is We should look upon man in the most the chief thing to understand. Let us say charitable light. It is not easy to be good. that here is an infinite line amid darkness. What are you but mere machines until We do not see the line, but on it there is one you are free? Should you be proud because luminous point which moves on. As it moves you are good? Certainly not. -

The Dasarupa a Treatise on Hindu Dramaturgy Columbia University Indo-Iranian Series

<K.X-."»3« .*:j«."3t...fc". wl ^^*je*w £gf SANfiNlRETAN V1SWABHARAT1 UBRARY ftlO 72, T? Siali • <••«.•• THE DASARUPA A TREATISE ON HINDU DRAMATURGY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY INDO-IRANIAN SERIES EDITED R Y A. V. WILLIAMS JACKSON FaOFCSSOR OF INOO-IRANIAH LANGUAGES IN COLUMBIA UNtVERSITY Volume 7 Neto York COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS 1912 AU righis reserved THE DASARUPA A TREATISE ON HINDU DRAMATURGY By DHANAMJAYA NOW FIRST TRANSLATED KROM THE SANSKRIT WITH THE TEXT AND AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY GEORGE C. O. HAAS, A.M., Ph.D. SOMKT1MB PBLLOW IN INDO-IftANIAN LANCOAGES JN COLUMBIA UNIVBRSITY Nrto Yor* COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS 1912 Alt rights reserved 2 Copyright 191 By Columbia University Press Printed from type. Auffiut, 1913 r«t*« ©r tMC MtV EKA PHtMTI«« COHM«r tAMCUTM. I»».. TO MY FATHER PREFATORY NOTE In the present volume an important treatise on the canons of dramatic composition in early India is published for the first time in an English translation, with the text, explanatory notes, and an introductory account of the author and his work. As a con- tribution to our knowledge of Hindu dramaturgy, I am glad to accord the book a place in the Indo-Iranian Series, particularly as it comes from one who has long been associated with me as a co-worker in the Oriental field. A. V. Williams Jackson. V» PREFACE The publication of the present volume, originally planned for 1909, has been delayed until now by ^arious contingencies both unforeseen and unavoidable. While in some respects unfortu- nate, this delay has been of advantagc in giving me opportunities for further investigation and enabling me to add considerably to my collection of comparative material. -

Lesson 81. Sanskrit Proverbs लोकोक्तयः

Lesson 81. Sanskrit Proverbs लोकोक्तयः Lokoktaya-s are different from the Nyaya-s in that a whole sentence is used to convey an idea and not just a couple of words. These proverbs are picked from subhashitas, poems, dramas..... the field is completely open. If the proverb is understood in the correct context, they can be used very artistically. For example, if your kid is giving you a tough time about taking Sanskrit lessons and you'd like him to begin, throw in the first proverb after your lecture for good measure! Some of these proverbs are explained in Hindi also. Also don't be surprised if two proverbs teach two completely opposite ideas. English does that too- Too many cooks spoil the broth vs. Many hands make light work! 1. अगच्छन व् नै तये ोऽपि िदमके ं न गच्छपत । A non-flying eagle does not move forward a single step. 2. अङ्कमा셁ह्य सप्तु ं पि ित्वा पकं नाम िौ셁षम ् । गोद म े सोय े ए को मारना िी क्या शरू ता ि ै ? Can killing one who is asleep on someone's lap constitute bravery? 3. अङ्गारः शतधौतने मपलनत्व ं न मञ्चु पत । कोयला सकै ड़ⴂ बार धोन े िर भी सफे द निĂ िोता । Coal does not loose its dirt (does not become white) even it were to be washed a hundred times. (People do not give up their intrinsic natures.) 4. अङ्गीकृ त ं सकु ृ पतनः िपरिालयपि । The virtuous make good their promise. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 3 3rd Pada 1st Adhikaranam to 36th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 66 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Introduction 2948 101 Sarvavedantapratyayadhikaranam 101 a) Sutra 1 2952 101 360 b) Sutra 2 2955 101 361 c) Sutra 3 2963 101 362 d) Sutra 4 2972 101 363 102 Upasamharadhikaranam 102 a) Sutra 5 2973 102 364 103 Anyathatvadhikaranam 103 a) Sutra 6 2976 103 365 b) Sutra 7 2986 103 366 c) Sutra 8 2991 103 367 104 Vyaptyadhikaranam 104 a) Sutra 9 2996 104 368 105 Sarvabhedadhikaranam 105 a) Sutra 10 3006 105 369 i S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 106 Anandadyadhikaranam 106 a) Sutra 11 3010 106 370 b) Sutra 12 3013 106 371 c) Sutra 13 3021 106 372 107 Adhyanadhikaranam 107 a) Sutra 14 3023 107 373 b) Sutra 15 3032 107 374 108 Atmagrihityadhikaranam 108 a) Sutra 16 3035 108 375 b) Sutra 17 3044 108 376 109 Karyakhyanadhikaranam 109 a) Sutra 18 3075 109 377 110 Samanadhikaranam 110 a) Sutra 19 3092 110 378 111 Sambandhadhikaranam 111 a) Sutra 20 3098 111 379 b) Sutra 21 3103 111 380 c) Sutra 22 3105 111 381 ii S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 112 Sambhrityadhikaranam 112 a) Sutra 23 3111 112 382 113 Purushavidyadhikaranam 113 a) Sutra 24 3117 113 383 114 Vedhadyadhikaranam 114 a) Sutra 25 3123 114 384 115 Hanyadhikaranam 115 a) Sutra 26 3130 115 385 116 Samparayadhikaranam 116 a) Sutra 27 3143 116 386 b) Sutra 28 3148 116 387 117 Gaterarthavattvadhikaranam 117 a) Sutra 29 3157 117 388 b) Sutra 30 3163 117 389 118 Aniyamadhikaranam 118 a) Sutra 31 3168 1118 390 119 Yavadadhikaradhikaranam 119 a) Sutra 32 3183 119 391 120 Aksharadhyadhikaranam 120 a) Sutra 33 3189 120 392 iii S. -

Asiatische Studien Etudes Asiatiques L U I • 1998

Schweizerische Asiengesellschaft Société Suisse-Asie 5 Asiatische Studien Etudes Asiatiques LUI • 1998 Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft Revue de la Société Suisse - Asie Peter Lang Bern • Berlin • Frankfurtam Main • New York • Paris • Wien ASIATISCHE STUDIEN ÉTUDES ASIATIQUES Herausgegeben von / Editées par JOHANNES BRONKHORST (Lausanne) - REINHARD SCHULZE (Bern) - ROBERT GASSMANN (Zürich) - EDUARD KLOPFENSTEIN (Zürich) - JACQUES MAY (Lausanne) - GREGOR SCHOELER (Basel) Redaktion: Ostasiatisches Seminar der Universität Zürich, Zürichbergstrasse 4, CH-8032 Zürich Die Asiatischen Studien erscheinen vier Mal pro Jahr. Redaktionstermin für Heft 1 ist der 15. September des Vorjahres, für Heft 2 der 15. Dezember, für Heft 3 der 15. März des gleichen Jahres und für Heft 4 der 15. Juni. Manuskripte sollten mit doppeltem Zeilenabstand geschrieben sein und im allgemeinen nicht mehr als vierzig Seiten umfassen. Anmerkungen, ebenfalls mit doppeltem Zeilenabstand geschrieben, und Glossar sind am Ende des Manuskriptes beizufügen (keine Fremdschriften in Text und Anmerkungen). Les Études Asiatiques paraissent quatre fois par an. Le délai rédactionnel pour le nu méro 1 est au 15 septembre de l’année précédente, pour le numéro 2 le 15 décembre, pour le numéro 3 le 15 mars de la même année et pour le numéro 4 le 15 juin. Les manuscrits doivent être dactylographiés en double interligne et ne pas excéder 40 pages. Les notes, en numérotation continue, également dactylographiées en double interligne, ainsi que le glossaire sont présentés à la fin du manuscrit. The Asiatische Studien are published four times a year. Manuscripts for publication in the first issue should be submitted by September 15 of the preceding year, for the second issue by December 15, for the third issue by March 15 and for the fourth issue by June 15. -

Madhya Pradesh Medical Science University Jabalpur (Mp)

MADHYA PRADESH MEDICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY JABALPUR (MP) SYLLABUS OF AYURVEDACHARYA (BAMS) COURSE INDEX 1ST PROFESSIONAL 1.1 PADARTHA VIGYAN AND AYURVED ITIHAS 2-6 1.2 SANSKRIT 7-8 1.3 KRIYA SHARIR 9-14 1.4 RACHANA SHARIR 15-18 1.5 MAULIK SIDDHANT AVUM ASTANG HRIDYA 19 1 1.1 PADARTHA VIGYAN EVUM AYURVEDA ITIHAS (Philosophy and History of Ayurveda) Theory- Two papers– 200 marks (100 each paper) Total teaching hours: 150 hours PAPER-I Padartha Vigyanam 100marks PART A 50 marks 1.Ayurveda Nirupana 1.1 Lakshana of Ayu, composition of Ayu. 1.2 Lakshana of Ayurveda. 1.3 Lakshana and classification of Siddhanta. 1.4 Introduction to basic principles of Ayurveda and their significance. 2. Ayurveda Darshana Nirupana 2.1 Philosophical background of fundamentals of Ayurveda. 2.2 Etymological derivation of the word “Darshana”. Classification and general introduction to schools of Indian Philosophy with an emphasis on: Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Sankhya and Yoga. 2.3 Ayurveda as unique and independent school of thought (philosophical individuality of Ayurveda). 2.4 Padartha: Lakshana, enumeration and classification, Bhava and Abhava padartha, Padartha according to Charaka (Karana-Padartha). 3. Dravya Vigyaniyam 3.1 Dravya: Lakshana, classification and enumeration. 3.2 Panchabhuta: Various theories regarding the creation (theories of Taittiriyopanishad, Nyaya-Vaisheshika, Sankhya-Yoga, Sankaracharya, Charaka and Susruta), Lakshana and qualities of each Bhoota. 3.3 Kaala: Etymological derivation, Lakshana and division / units, significance in Ayurveda. 3.4 Dik: Lakshana and division, significance in Ayurveda. 3.5 Atma:Lakshana, classification, seat, Gunas, Linga according to Charaka, the method / process of knowledge formation (atmanah jnasya pravrittih). -

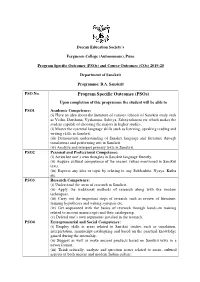

Program Specific Outcomes (Psos) and Course Outcomes (Cos) 2019-20

Deccan Education Society’s Fergusson College (Autonomous), Pune Program Specific Outcomes (PSOs) and Course Outcomes (COs) 2019-20 Department of Sanskrit Programme: B.A. Sanskrit PSO No. Program Specific Outcomes (PSOs) Upon completion of this programme the student will be able to PSO1 Academic Competence: (i) Have an idea about the literature of various schools of Sanskrit study such as Vedas, Darshana, Vyakarana, Sahitya, Sahityashastra etc which makes the student capable of choosing the majors in higher studies. (i) Master the essential language skills such as listening, speaking reading and writing skills in Sanskrit. (iii) Demonstrate understanding of Sanskrit language and literature through translations and performing arts in Sanskrit. (iv) Analyze and interpret primary texts in Sanskrit. PSO2 Personal and Professional Competence: (i) Articulate one’s own thoughts in Sanskrit language fluently. (ii) Acquire cultural competence of the ancient values mentioned in Sanskrit texts. (iii) Express any idea or topic by relating to any Subhashita, Nyaya, Katha etc. PSO3 Research Competence: (i) Understand the areas of research in Sanskrit. (ii) Apply the traditional methods of research along with the modern techniques. (iii) Carry out the important steps of research such as review of literature, framing hypotheses and writing synopsis etc. (iv) Get acquainted with the basics of research through hands-on training related to ancient manuscripts and their cataloguing. (v) Defend one’s own arguments justified in the research. PSO4 Entrepreneurial and Social Competence: (i) Employ skills in areas related to Sanskrit studies such as translation, interpretation, manuscript-cataloguing and based on the practical knowledge gained during the internship. (ii) Suggest as well as make ancient products based on Sanskrit texts in a newer format. -

Influence of Ramayana on the Life, Culture and Literature in India and Abroad Ramayana Dr.Y.RAMESH Associate Professor Department of History & P.G

ISSN XXXX XXXX © 2016 IJESC Research Article Volume 6 Issue No. 8 Influence of Ramayana on the Life, Culture and Literature in India and Abroad Ramayana Dr.Y.RAMESH Associate Professor Department of History & P.G. Centre Government Arts College, Bangalore, Karnataka, India Abstract The Valmiki-Ramayana is a splendid creation of the sublime thoughts of Valmiki, the seer poet; it serves as a source of eternal inspiration, salutary ideas and moral behaviour for millions of people all over the world. It transcends the limitations of time, place and circumstances and presents an universal appeal to people speaking different languages, dwelling different countries and h aving different religious persuasions. The Vedas and the Puranas along with two great epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata constitute the solid and enduring foundation of age long and magnificent edifice of Indian culture and civilization. The ever -las ting appeal of these treatises still influences, to a great extent, the cultural life and behaviour-pattern of crores of Indians. Introduction exercised such a stupendous influence on the mind, life and thoughts of the masses. The epic portrays many-sided picture Anybody, intending to know India’s present properly, even of a perfect life. The story of the Ramayana reveals the unwillingly, goes through its thriving past history; because in conquest of good over evil. Valmiki composes the epic, order to know the present of a nation properly, one cannot merging religion with morality and statesmanship with ignore its past history and cultural heritage. If we look into the common sense, in such a manner that it presents an excellent great epics, all the traditional characteristics of Indian combination of sociology, philosophy, Arthasastra, History civilization, along with its magnanimity as well as deficiency and ethics. -

Report of a Second Tour in Search of Sanskrit Manuscripts Made In

if^- IPfipi^ti:^ i:il,p:Pfiliif!f C\J CO 6605 S3B49 1907 c- 1 ROBA RErORT OK A SECOND TOUR IN EARCH OF SANSKRIT MANUSCRIPTS MADE IN- RAJPUTANA AND CENTRAL INDIA TN 1904-5 AND 1905-6. BY SHRIDHAR R. BHANDARKAB, M.A.^ Professor of SansTcrity FJiyhinstone Collegt. BOMBAY PRINTED AT THE GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS 19C7 I'l'^'^Sf i^^s UBRA^ CCI2 , . 5 1995 'V- No. 72 OF 1906-07. Elphinsione College^ Bomhay^ 20lh February 1907. To The director op PUBLIC INSTRUCTION, Poona. Sir, * I have the honour to submit the following report of the tours I made through Central India and Rajputana in the beginning of 1905 and that of 1906 in accordance with the Resolutions of Government, Nos. 2321 and 660 in the Educational Department, dated the 14th December 1904 and 12th April 1905, respectively. 2. A copy of the first resolution reached me during the Christ- mas holidays of 1904^ but it was February before I could be relieved of my duties at College. So I started on my tour in February soon after I was relieved. 3. The place I was most anxious to visit first for several reasons was Jaisalmer. It lies in the midst of a sandy desert, ninety miles from the nearest railway station, a journey usually done on camel back. Dr. Biihler, who had visited the place in January 1874, had remarked about ^* the tedious journey and the not less tedious stay in this country of sand, bad water, and guinea-worms,'' and the Resident of the Western Rajputana States, too, whom I had seen in January 1904, had spoken to me of the very tedious and troublesome nature of the journey. -

Role of Subhashitas in Creating a Model Society

JASC: Journal of Applied Science and Computations ISSN NO: 1076-5131 ROLE OF SUBHASHITAS IN CREATING A MODEL SOCIETY V. RAGHAVENDRAN Dr. NIDHI RASTOGI Research Scholar Associate Professor OPJS University, Rajasthan. OPJS University, Rajasthan. Abstract Objective Subhashitas are simple short epigrammatic poetic verses which convey treasured messages through interesting examples. Our rich Sanskrit heritage has subhashitas relevant to all arenas of life. In our traditional Indian education system Subhashitas are mainly taught to the children at very early age, especially choosing the ones related to righteousness, truthfulness, knowledge, education, service, friendship, courage and patriotism. These subhashitas quote elegant practical examples in them. They guide the children in distinguishing between the good and the bad, help them in deciding “what to do” and “what not to do” by projecting the virtues of the good and showcasing the ill effects of the bad. When the children grow up memorizing and listening to these subhashitas, they imbibe the morale values which the subhashita portrays and become good citizen of our nation. “Today‟s children are tomorrow‟s citizen”, it is our citizen who create a model society, and they do it based on their personality, education, thinking abilities and the values inherent in them. The main object of this research is to demonstrate that subhashitas act as one of the key ingredients in creating a model society. Design / Methodology/ Approach- Methodology followed in this research is Qualitative analysis and this work is conceptualized based on various reference materials which are collections of subhashitas, websites which has subhashitas on multiple subjects and research paper related to this subject. -

M.A. Sanskrit Syllabus and Text Books

M.A. Sanskrit (under semester system w.e.f. 2004 admitted batch onwards) Syllabus and text books There will be four semesters in order to complete the M.A. Degree. Two semesters in the first year and two semesters in the final year. A candidate will be declared to have passed the examination if he has passed all the four semester examinations in all the papers. Each paper will be for maximum of hundred marks. The total No. of papers for all the semesters will be twenty. REGULATIONS: 1. The semester end examination shall be based on the question paper set by an external Examiner or paper setter and there will be a double valuation. 2. Specializations offered : Alankara, Vyakarana, Darsana and Kavya. Out of these four specials presently instruction is given for only two specials Alankara & Kavya . Dur to shortage of faculty . Total papers 20 Common papers 14 Specials 06 Internals – Two Mid sem exams of 15 marks each SCHEME OF EXAMINATION M.A.SANSKRIT Serial No. of the Paper Title of the subject Marks I SEMESTER Compulsory Paper I Vedic Language & Literature 100 Compulsory Paper II Grammar and Linguistics 100 Compulsory Paper III Darsana 100 Compulsory Paper IV Poetics and Aesthetics 100 Compulsory Paper V Kavya: Prose, Poetry & Drama 100 II SEMESTER Compulsory Paper I Vedic language & Literature 100 Compulsory Paper II Grammar and Linguistics 100 Compulsory Paper III Darsana 100 Compulsory Paper IV Poetics and Aesthetics 100 Compulsory Paper V Kavya: Prose, Poetry & Drama 100 III SEMESTER Compulsory Paper VI Culture & History 100 Special-