Television As a Teacher. a Research Monograph. INSTITUTION National Inst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Jul 1

The Fifth Estate Broadcasting Jul 1 You'll find more women watching Good Company than all other programs combined: Company 'Monday - Friday 3 -4 PM 60% Women 18 -49 55% Total Women Nielsen, DMA, May, 1985 Subject to limitations of survey KSTP -TV Minneapoliso St. Paul [u nunc m' h5 TP t 5 c e! (612) 646 -5555, or your nearest Petry office Z119£ 1V ll3MXVW SO4ii 9016 ZZI W00b svs-lnv SS/ADN >IMP 49£71 ZI19£ It's hours past dinner and a young child hasn't been seen since he left the playground around noon. Because this nightmare is a very real problem .. When a child is missing, it is the most emotionally exhausting experience a family may ever face. To help parents take action if this tragedy should ever occur, WKJF -AM and WKJF -FM organized a program to provide the most precise child identification possible. These Fetzer radio stations contacted a local video movie dealer and the Cadillac area Jaycees to create video prints of each participating child as the youngster talked and moved. Afterwards, area law enforce- ment agencies were given the video tape for their permanent files. WKJF -AM/FM organized and publicized the program, the Jaycees donated man- power, and the video movie dealer donated the taping services-all absolutely free to the families. The child video print program enjoyed area -wide participation and is scheduled for an update. Providing records that give parents a fighting chance in the search for missing youngsters is all a part of the Fetzer tradition of total community involvement. -

Afterschool for the Global Age

Afterschool for the Global Age Asia Society The George Lucas Educational Foundation Afterschool and Community Learning Network The Children’s Aid Society Center for Afterschool and Community Education at Foundations, Inc. Asia Society Asia Society is an international nonprofi t organization dedicated to strengthening relationships and deepening understanding among the peoples of Asia and the United States. The Society seeks to enhance dialogue, encourage creative expression, and generate new ideas across the fi elds of policy, business, education, arts, and culture. Through its Asia and International Studies in the Schools initiative, Asia Society’s education division is promoting teaching and learning about world regions, cultures, and languages by raising awareness and advancing policy, developing practical models of international education in the schools, and strengthening relationships between U.S. and Asian education leaders. Headquartered in New York City, the organization has offi ces in Hong Kong, Houston, Los Angeles, Manila, Melbourne, Mumbai, San Francisco, Shanghai, and Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2007 by the Asia Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For more on international education and ordering -

Sesame Street Combining Education and Entertainment to Bring Early Childhood Education to Children Around the World

SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION TO CHILDREN AROUND THE WORLD Christina Kwauk, Daniela Petrova, and Jenny Perlman Robinson SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO Sincere gratitude and appreciation to Priyanka Varma, research assistant, who has been instrumental BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD in the production of the Sesame Street case study. EDUCATION TO CHILDREN We are also thankful to a wide-range of colleagues who generously shared their knowledge and AROUND THE WORLD feedback on the Sesame Street case study, including: Sashwati Banerjee, Jorge Baxter, Ellen Buchwalter, Charlotte Cole, Nada Elattar, June Lee, Shari Rosenfeld, Stephen Sobhani, Anita Stewart, and Rosemarie Truglio. Lastly, we would like to extend a special thank you to the following: our copy-editor, Alfred Imhoff, our designer, blossoming.it, and our colleagues, Kathryn Norris and Jennifer Tyre. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Support for this publication and research effort was generously provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and The MasterCard Foundation. The authors also wish to acknowledge the broader programmatic support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the LEGO Foundation, and the Government of Norway. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. -

Doing Business in Malaysia: 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S

Doing Business in Malaysia: 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2010-2014. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. Chapter 1: Doing Business In Malaysia Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment Chapter 5: Trade Regulations, Customs and Standards Chapter 6: Investment Climate Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing Chapter 8: Business Travel Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services Return to table of contents Chapter 1: Doing Business In Malaysia Market Overview Market Challenges Market Opportunities Market Entry Strategy Market Overview Return to top For centuries, Malaysia has profited from its location at a crossroads of trade between the East and West, a tradition that carries into the 21st century. Geographically blessed, peninsular Malaysia stretches the length of the Strait of Malacca, one of the most economically and politically important shipping lanes in the world. Capitalizing on its location, Malaysia has been able to transform its economy from an agriculture and mining base in the early 1970s to a relatively high-tech, competitive nation, where services and manufacturing now account for 75% of GDP (51% in services and 24% in manufacturing in 2013). In 2013, U.S.-Malaysia bilateral trade was an estimated US$44.2 billion counting both manufacturing and services,1 ranking Malaysia as the United States’ 20th largest trade partner. Malaysia is America’s second largest trading partner in Southeast Asia, after Singapore. -

Sanibona Bangane! South Africa

2003 ANNUAL REPORT sanibona bangane! south africa Takalani Sesame Meet Kami, the vibrant HIV-positive Muppet from the South African coproduction of Sesame Street. Takalani Sesame on television, radio and through community outreach promotes school readiness for all South African children, helping them develop basic literacy and numeracy skills and learn important life lessons. bangladesh 2005 Sesame Street in Bangladesh This widely anticipated adaptation of Sesame Street will provide access to educational opportunity for all Bangladeshi children and build the capacity to develop and sustain quality educational programming for generations to come. china 1998 Zhima Jie Meet Hu Hu Zhu, the ageless, opera-loving pig who, along with the rest of the cast of the Chinese coproduction of Sesame Street, educates and delights the world’s largest population of preschoolers. japan 2004 Sesame Street in Japan Japanese children and families have long benefited from the American version of Sesame Street, but starting next year, an entirely original coproduction designed and produced in Japan will address the specific needs of Japanese children within the context of that country’s unique culture. palestine 2003 Hikayat Simsim (Sesame Stories) Meet Haneen, the generous and bubbly Muppet who, like her counterparts in Israel and Jordan, is helping Palestinian children learn about themselves and others as a bridge to cross-cultural respect and understanding in the Middle East. egypt 2000 Alam Simsim Meet Khokha, a four-year-old female Muppet with a passion for learning. Khokha and her friends on this uniquely Egyptian adaptation of Sesame Street for television and through educational outreach are helping prepare children for school, with an emphasis on educating girls in a nation with low literacy rates among women. -

Biomedicine and Makeover TV DISSERTATION

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Bio-logics of Bodily Transformation: Biomedicine and Makeover TV DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Visual Studies by Corella Ann Di Fede Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Lucas Hilderbrand, Chair Associate Professor Fatimah Tobing Rony Associate Professor Jennifer Terry Assistant Professor Allison Perlman 2016 © 2016 Corella Ann Di Fede DEDICATION To William Joseph Di Fede, My brother, best friend and the finest interlocutor I will ever have had. He was the twin of my own heart and mind, and I am not whole without him. My mother for her strength, courage and patience, and for her imagination and curiosity, My father whose sense of humor taught me to think critically and articulate myself with flare, And both of them for their support, generosity, open-mindedness, and the care they have taken in the world to live ethically, value every life equally, and instill that in their children. And, to my Texan and Sicilian ancestors for lending me a history full of wild, defiant spirits ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vii INTRODUCTION 1 Biopolitical Governance in Pop Culture: Neoliberalism, Biomedicine, and TV Format 3 Health: Medicine, Morality, Aesthetics and Political Futures 11 Biomedicalization, the Norm, and the Ideal Body 15 Consumer-patient, Privatization and Commercialization of Life 20 Television 24 Biomedicalized Regulation: Biopolitics and the Norm 26 Emerging -

Public Taste: a Comparison of Movie Popularity and Critical Opinion

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1982 Public taste: A comparison of movie popularity and critical opinion R. Claiborne Riley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Riley, R. Claiborne, "Public taste: A comparison of movie popularity and critical opinion" (1982). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625207. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-hqz7-rj05 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLIC TASTE: A COMPARISON OF MOVIE u POPULARITY AND CRITICAL OPINION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Sociology The College of William, and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by R. Claiborne Riley 1982 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts R. Claiborne Riley Approved, September 1982 r**1. r i m f Satoshi Ito JL R. Wayne Kernodle Marion G. Vanfossen TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......... iv LIST OF TABLES . ..... .... ..................... v ABSTRACT .......... '......... vi INTRODUCTION .......... ...... 2 Chapter I. THE MOVIES: AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE .............. 6 Chapter II. THE AUDIENCE ........................................ 51 Chapter III. THE C R I T I C ............ 61 Chapter IV. THE WANDERER STUDY AND DUMAZEDIER ON MOVIES AND LEISURE ....... -

Menlo Park Juvi Dvds Check the Online Catalog for Availability

Menlo Park Juvi DVDs Check the online catalog for availability. List run 09/28/12. J DVD A.LI A. Lincoln and me J DVD ABE Abel's island J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Ociee Nash J DVD ADV The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin. J DVD ADV The adventures of Pinocchio J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE 2 Agent Cody Banks 2 J DVD AIR Air Bud J DVD AIR Air buddies J DVD ALA Aladdin J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALICE Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALL All dogs go to heaven J DVD ALL All about fall J DVD ALV Alvin and the chipmunks. -

Children's Rights and the Media

Centre for the Study of Communication and Culture Volume 28 (2009) No. 3 IN THIS ISSUE Children’s Rights and the Media Katharine Heintz, Guest Editor Santa Clara University AQUARTERLY REVIEW OF COMMUNICATION RESEARCH ISSN: 0144-4646 Communication Research Trends Volume 28 (2009) Number 3 Table of Contents http://cscc.scu.edu Children’s Rights and the Media Published four times a year by the Centre for the Study of Introduction . 3 Communication and Culture (CSCC), sponsored by the Guest Editor’s Introduction . 4 California Province of the Society of Jesus. Copyright 2009. ISSN 0144-4646 Rethinking and Reframing Media Effects in the Context of Children’s Rights: Editor: William E. Biernatzki, S.J. A New Paradigm Managing Editor: Paul A. Soukup, S.J. Michael Rich . 7 Subscription: Annual subscription (Vol. 28) US$50 A Rationale for Positive Online Content for Children Payment by check, MasterCard, Visa or US$ preferred. Sonia Livingstone . 12 For payments by MasterCard or Visa, send full account number, expiration date, name on account, and signature. Television as a “Safe Space” for Children: The Views of Producers around the World Checks and/or International Money Orders (drawn on Dafna Lemish . 17 USA banks; for non-USA banks, add $10 for handling) should be made payable to Communication Research Youth Media around the World: Implications Trends and sent to the managing editor for Communication and Media Studies Paul A. Soukup, S.J. JoEllen Fisherkeller . 21 Communication Department Santa Clara University Creating Global Citizens: The Panwapa Project 500 El Camino Real June H. Lee & Charlotte F. Cole . 25 Santa Clara, CA 95053 USA Transfer by wire: Contact the managing editor. -

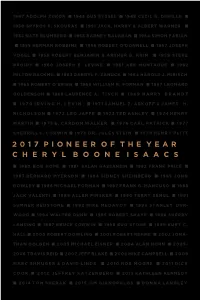

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

Sesame Street

Sesame Street The first TV show to achieve early-childhood learning gains, launched in the United States in the late 1960s, is now viewed by more than 156 million children around the world. In the mid-1960s, a new wave of research revealed the depths of unmet This case study is part of a series that accompanies The Bridgespan Group article educational needs of impoverished “Audacious Philanthropy: Lessons from 15 World-Changing Initiatives” (Harvard preschool-age children and the high Business Review, Sept/Oct 2017). See below for 15 stories of social movements costs of addressing these needs via that defied the odds and learn how traditional classroom-based programs philanthropy played a role in achieving their life-changing results. like Head Start. Against this backdrop, • The Anti-Apartheid Movement the concept of using television as • Aravind Eye Hospital a vehicle to improve early childhood • Car Seats • CPR Training education at scale came up at a • The Fair Food Program 1966 dinner conversation between • Hospice and Palliative Care documentarian Joan Ganz Cooney • Marriage Equality • Motorcycle Helmets in Vietnam and Carnegie Corporation of New York • The National School Lunch Program Vice President Lloyd Morrisett. • 911 Emergency Services • Oral Rehydration Together, they developed the concept and launched • Polio Eradication a new program they called Sesame Street, and by 1993, 77 percent of all preschoolers in the • Public Libraries United States watched the show at least once a • Sesame Street week, including 88 percent of those from low- • Tobacco Control income families, with significant positive effects. Among other outcomes, a recent study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that children who watched were more likely to be kindergarten-ready and an estimated 30 to 50 percent less likely to fall behind grade level, with the greatest impacts on the most disadvantaged children. -

UNIVERSAL TV-Leading Supplier of TV Series to the Itself of the Talent

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF TELEVISION 441 UNIVERSAL TV-leading supplier of TV series to the period. Robert Stack played Eliot Ness, head of the "un- networks since the mid -60s, usually having three times the touchable" government agents cracking down on the mobs. number of weekly hours on the air as the runner-up Hol- Although it was highly popular, the series was attacked lywood studio. A subsidiary of Universal Pictures, UTV has by Italian -American groups for ethnic defamation and by been responsible for such series as Ironside, Kojak, Columbo, others for the sensationalism of machine-gun murders and Baretta, Emergency, The Rockford Files, Rich Man, Poor Man acts of brutality. It was produced by Quinn Martin for and the NBC World Premiere movies, among scores of other Desilu, in association with Langford Productions. shows. Its sister company, MCA -TV, engaged in domestic and foreign syndication, habitually turns huge profits from the network hits through the sale of reruns. Universal Pictures was a foundering company when the talent agency MCA (originally, Music Corp. of America) bought control of the studio in 1962. MCA then divested itself of the talent agency and concentrated on making movies, television series and recordings (it had also pur- chased Decca Records). Earlier, MCA had bought the old Republic film studios and created Revue Productions, which turned out low -budget TV series. With Universal, MCA Inc. had the largest studio in Hollywood and the best- equipped backlot, and the show -business savvy of its princi- pal officers, Jules Stein and Lew Wasserman, quickly turned the facilities into a giant TV production source.