Integrating Chinese Culture Into Sesame Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transmedia Muppets: the Possibilities of Performer Narratives

Volume 5, Issue 2 September 2012 Transmedia Muppets: The Possibilities of Performer Narratives AARON CALBREATH-FRASIEUR, University of Nottingham ABSTRACT This article examines how the Muppets franchise engages with transmedia narratives, their stories moving fluidly between television, film, comics, the internet and more. Rather than highlight the complexity Henry Jenkins (2006), Elizabeth Evans (2011) and others associate with transmedia, an examination of the Muppets offers insight into a mechanism that allows for simpler coherent connection between texts. The Muppets’ ongoing performer narrative challenges the prevailing understanding of transmedia storytelling. As performative characters (singers, actors, performance artists), any text concerned with Muppets, even those in which they act as other characters, becomes part of an overarching Muppet narrative. A high degree of self-reflexivity further supports transmediality, as most Muppet texts contain references to that text as a performance by the Muppets. Thus the comic Muppet Robin Hood and the film Muppet Treasure Island continue the story of the Muppets as further insight is gained into the characters' personalities and ongoing performance history. Examining different iterations of the Muppets franchise illuminates the ramifications of performer narratives for transmedia storytelling. KEYWORDS Transmedia storytelling, franchise, narrative, Muppets, multi-platform For over fifty-five years the Muppets have been appearing in media texts. They began on local television but have spread across most contemporary mediums, with many of these texts part of the over-arching, ongoing Muppet story. This article explores an alternative framework for defining one form of transmedia storytelling. This model suggests a complication in the understanding of transmedia storytelling put forward by Henry Jenkins (2006) and Elizabeth Evans (2011). -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 329 218 IR 014 857 TITLE Development Communication Report, 1990/1-4, Nos. INSTITUTION Agency for Internationa

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 329 218 IR 014 857 TITLE Development Communication Report, 1990/1-4, Nos. 68-71. INSTITUTION Agency for International Development (IDCA), Washington, DC. Clearinghouse on Development Communication. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 74p.; For the 1989 issues, see ED 319 394. AVAILABLE FROMClearinghouse on Development Communication, 1815 North Fort Meyers Dr., Suite 600, Arlington, VA 22209. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) JOURNAL CIT Development Communication Report; n68-71 1990 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Literacy; *Basic Skills; Change Strategies; Community Education; *Developing Nations; Development Communication; Educational Media; *Educational Technology; Educational Television; Feminism; Foreign Countries; *Health Education; *Literacy Education; Mass Media Role; Public Television; Sex Differences; Teaching Models; Television Commercials; *Womens Education ABSTRACT The four issues of this newsletter focus primarily on the use of communication technologies in developing nations tc educate their people. The first issue (No. 68) contains a review of the current status of adult literacy worldwide and articles on an adult literacy program in Nepal; adult new readers as authors; testing literacy materials; the use Jf hand-held electronic learning aids at the primary level in Belize; the use of public television to promote literacy in the United States; reading programs in Africa and Asia; and discussions of the Laubach and Freirean literacy models. Articles in the second issue (no. 69) discuss the potential of educational technology for improving education; new educational partnerships for providing basin education; gender differences in basic education; a social marketing campaign and guidelines for the improvement of basic education; adaptations of educational television's "Sesame Street" for use in other languages and cultures; and resources on basic education. -

En Vogue Ana Popovic Artspower National Touring Theatre “The

An Evening with Jazz Trumpeter Art Davis Ana Popovic En Vogue Photo Credit: Ruben Tomas ArtsPower National Alyssa Photo Credit: Thomas Mohr Touring Theatre “The Allgood Rainbow Fish” Photo Courtesy of ArtsPower welcome to North Central College ometimes good things come in small Ana Popovic first came to us as a support act for packages. There is a song “Bigger Isn’t Better” Jonny Lang for our 2015 homecoming concert. S in the Broadway musical “Barnum” sung by When she started on her guitar, Ana had everyone’s the character of Tom Thumb. He tells of his efforts attention. Wow! I am fond of telling people who to prove just because he may be small in stature, he have not been in the concert hall before that it’s a still can have a great influence on the world. That beautiful room that sounds better than it looks. Ana was his career. Now before you think I have finally Popovic is the performer equivalent of my boasts lost it, there is a connection here. February is the about the hall. The universal comment during the smallest month, of the year, of course. Many people break after she performed was that Jonny had better feel that’s a good thing, given the normal prevailing be on his game. Lucky for us, of course, he was. But weather conditions in the month of February in the when I was offered the opportunity to bring Ana Chicagoland area. But this little month (here comes back as the headliner, I jumped at the chance! Fasten the connection!) will have a great influence on the your seatbelts, you are in for an amazing evening! fine arts here at North Central College with the quantity and quality of artists we’re bringing to you. -

Afterschool for the Global Age

Afterschool for the Global Age Asia Society The George Lucas Educational Foundation Afterschool and Community Learning Network The Children’s Aid Society Center for Afterschool and Community Education at Foundations, Inc. Asia Society Asia Society is an international nonprofi t organization dedicated to strengthening relationships and deepening understanding among the peoples of Asia and the United States. The Society seeks to enhance dialogue, encourage creative expression, and generate new ideas across the fi elds of policy, business, education, arts, and culture. Through its Asia and International Studies in the Schools initiative, Asia Society’s education division is promoting teaching and learning about world regions, cultures, and languages by raising awareness and advancing policy, developing practical models of international education in the schools, and strengthening relationships between U.S. and Asian education leaders. Headquartered in New York City, the organization has offi ces in Hong Kong, Houston, Los Angeles, Manila, Melbourne, Mumbai, San Francisco, Shanghai, and Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2007 by the Asia Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For more on international education and ordering -

Sesame Street Combining Education and Entertainment to Bring Early Childhood Education to Children Around the World

SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION TO CHILDREN AROUND THE WORLD Christina Kwauk, Daniela Petrova, and Jenny Perlman Robinson SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO Sincere gratitude and appreciation to Priyanka Varma, research assistant, who has been instrumental BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD in the production of the Sesame Street case study. EDUCATION TO CHILDREN We are also thankful to a wide-range of colleagues who generously shared their knowledge and AROUND THE WORLD feedback on the Sesame Street case study, including: Sashwati Banerjee, Jorge Baxter, Ellen Buchwalter, Charlotte Cole, Nada Elattar, June Lee, Shari Rosenfeld, Stephen Sobhani, Anita Stewart, and Rosemarie Truglio. Lastly, we would like to extend a special thank you to the following: our copy-editor, Alfred Imhoff, our designer, blossoming.it, and our colleagues, Kathryn Norris and Jennifer Tyre. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Support for this publication and research effort was generously provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and The MasterCard Foundation. The authors also wish to acknowledge the broader programmatic support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the LEGO Foundation, and the Government of Norway. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. -

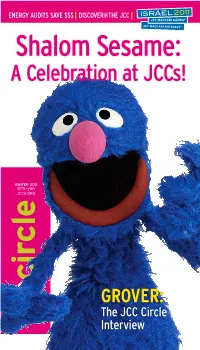

Shalom Sesame: a Celebration at Jccs!

energy audits save $$$ | discover@the jcc | shalom sesame: a celebration at JCCs! winter 2011 5771 qruj jcca.org circle Grover: the JCC circle interview insidewinter 2011 5771 qruj www.jcca.org Encouraging Jewish engagement 2 Allan Finkelstein DISCOVER @ THE JCC 4 Transcending fitness Viva Tel Aviv! 10 The other city that never sleeps Israel 2011: A dream come true 14 JCC Maccabi Games and ArtsFest in Eretz Yisrael Five secrets to building a great 18 board-executive relationship With Gary LIpman Nashville Journal: 20 Floodwaters, Gordon JCC rise to the occasion It’s money in the bank 22 Why you ought to have an energy audit now Grover: A world-traveler visits Israel 26 The JCC Circle interview Shalom Sesame and engaging families 28 The premiere is just the beginning Securing professional talent 32 Who will lead your JCC in ten years? For address correction or information about JCC Circle contact [email protected] or call (212) 532-4949. ©2010 jewish community centers association of north america. all rights reserved. 520 eighth avenue | new York, nY 10018 Phone: 212-532-4949 | Fax: 212-481-4174 | e-mail: [email protected] | web: www.jcca.org JCC association of north america is the leadership network of, and central agency for, 350 jewish community centers, YM-YwHas and camps in the United States and canada, that annually serve more than two million users. JCC association offers a wide range of services and resources to enable its affiliates to provide educational, cultural and recreational programs to enhance the lives of north american jewry. JCC association is also a U.S. -

Sanibona Bangane! South Africa

2003 ANNUAL REPORT sanibona bangane! south africa Takalani Sesame Meet Kami, the vibrant HIV-positive Muppet from the South African coproduction of Sesame Street. Takalani Sesame on television, radio and through community outreach promotes school readiness for all South African children, helping them develop basic literacy and numeracy skills and learn important life lessons. bangladesh 2005 Sesame Street in Bangladesh This widely anticipated adaptation of Sesame Street will provide access to educational opportunity for all Bangladeshi children and build the capacity to develop and sustain quality educational programming for generations to come. china 1998 Zhima Jie Meet Hu Hu Zhu, the ageless, opera-loving pig who, along with the rest of the cast of the Chinese coproduction of Sesame Street, educates and delights the world’s largest population of preschoolers. japan 2004 Sesame Street in Japan Japanese children and families have long benefited from the American version of Sesame Street, but starting next year, an entirely original coproduction designed and produced in Japan will address the specific needs of Japanese children within the context of that country’s unique culture. palestine 2003 Hikayat Simsim (Sesame Stories) Meet Haneen, the generous and bubbly Muppet who, like her counterparts in Israel and Jordan, is helping Palestinian children learn about themselves and others as a bridge to cross-cultural respect and understanding in the Middle East. egypt 2000 Alam Simsim Meet Khokha, a four-year-old female Muppet with a passion for learning. Khokha and her friends on this uniquely Egyptian adaptation of Sesame Street for television and through educational outreach are helping prepare children for school, with an emphasis on educating girls in a nation with low literacy rates among women. -

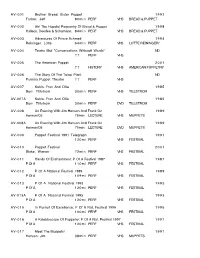

To Download a PDF of the Guild's Library List

AV-001 Brother Bread, Sister Puppet 1 9 9 2 Farber, Jeff 80min PERF VHS BREAD & PUPPET AV-002 Ah! The Hopeful Pageantry Of Bread & Puppet 1 9 9 8 Halleck, Deedee & Schumann, 84min PERF VHS BREAD & PUPPET AV-003 Adventures Of Prince Achmed 1 9 9 4 Reininger, Lotte 64min PERF VHS LOTTE REININGER/ AV-004 Teatro Muf "Conversations Withoutt Words" ND ? ? PERF VHS AV-005 The American Puppet 2 0 0 1 ? ? HISTORY VHS AMERICAN PUPPETRY AV-006 The Story Of The Tulasi Plant ND Purnina Puppet Theatre ? ? PERF VHS AV-007 Kukla, Fran And Ollie 1 9 8 5 Burr Tillstrom 30min PERF VHS TILLSTROM AV-007A Kukla, Fran And Ollie 1 9 8 5 Burr Tillstrom 30min PERF DVD TILLSTROM AV-008 An Evening With Jim Henson And Frank Oz 1 9 8 9 Henson/Oz 75min LECTURE VHS MUPPETS AV-008A An Evening With Jim Henson And Frank Oz 1 9 8 9 Henson/Oz 75min LECTURE DVD MUPPETS AV-009 Puppet Festival 1991 Telegraph 1 9 9 1 1 2 0 m i PERF VHS FESTIVAL AV-010 Puppet Festival 2 0 0 1 Blake, Warner 72min PERF VHS FESTIVAL AV-011 Hands Of Enchantment: P Of A Festival 1987 1 9 8 7 P Of A 1 1 0 m i PERF VHS FESTIVAL AV-012 P Of A National Festival 1989 1 9 8 9 P Of A 1 0 9 m i PERF VHS FESTIVAL AV-013 P Of A National Festival 1993 1 9 9 3 P Of A 1 2 0 m i PERF VHS FESTIVAL AV-013A P Of A National Festival 1993 1 9 9 3 P Of A 1 2 0 m i PERF VHS FESTIVAL AV-015 In Pursuit Of Excellence: P Of A Nat. -

Muppets Now Fact Sheet As of 6.22

“Muppets Now” is The Muppets Studio’s first unscripted series and first original series for Disney+. In the six- episode season, Scooter rushes to make his delivery deadlines and upload the brand-new Muppet series for streaming. They are due now, and he’ll need to navigate whatever obstacles, distractions, and complications the rest of the Muppet gang throws at him. Overflowing with spontaneous lunacy, surprising guest stars and more frogs, pigs, bears (and whatevers) than legally allowed, the Muppets cut loose in “Muppets Now” with the kind of startling silliness and chaotic fun that made them famous. From zany experiments with Dr. Bunsen Honeydew and Beaker to lifestyle tips from the fabulous Miss Piggy, each episode is packed with hilarious segments, hosted by the Muppets showcasing what the Muppets do best. Produced by The Muppets Studio and Soapbox Films, “Muppets Now” premieres Friday, July 31, streaming only on Disney+. Title: “Muppets Now” Category: Unscripted Series Episodes: 6 U.S. Premiere: Friday, July 31 New Episodes: Every Friday Muppet Performers: Dave Goelz Matt Vogel Bill Barretta David Rudman Eric Jacobson Peter Linz 1 6/22/20 Additional Performers: Julianne Buescher Mike Quinn Directed by: Bill Barretta Rufus Scot Church Chris Alender Executive Producers: Andrew Williams Bill Barretta Sabrina Wind Production Company: The Muppets Studio Soapbox Films Social Media: facebook.com/disneyplus twitter.com/disneyplus instagram.com/disneyplus facebook.com/muppets twitter.com/themuppets instagram.com/themuppets #DisneyPlus #MuppetsNow Media Contacts: Disney+: Scott Slesinger Ashley Knox [email protected] [email protected] The Muppets Studio: Debra Kohl David Gill [email protected] [email protected] 2 6/22/20 . -

The Muppets (2011

The Muppets (2011. Comedy. Rated PG. Directed by James Bobin) A Muppet fanatic and two humans in a budding relationship mobilize the Muppets, now scattered all over the world, to help save the Muppets’ beloved theater from being torn down. Songs, laughter tears ensue. Starring Jason Segel, Amy Adams, Chris Cooper, Steve Whitmire, Eric Jacobsen, David Goelz, Bill Barretta. The scenes of Kermit and friends driving across the country are in Tahoe (standing in for the snowy Rocky Mountains) and rural Lincoln in Western Placer County along Wise Road and various cross streets (standing in as the Midwest). Notice the beautiful, green fields along the roadways. \ Some of the road views can be seen from inside Kermit’s car, looking out. Other scenes feature the exterior of the car driving down county roads. The Muppets shot here in part because Placer County diverse terrain is a good substitute for many parts of the US; many other productions have done the same. This was the second time Kermit shot in Placer County. He filmed here for a few days in 2006, for a Superbowl commercial for the Ford Escape Hybrid (at Euchre Bar Tail Head/Iron Point near Alta, CA). Phenomenon (1996. Romantic fantasy. Rated PG. Directed by Jon Turteltaub) An amiable ordinary man of modest ambitions in a small town is inexplicably transformed into a genius. Starring John Travolta, Kyra Sedgewick, Forest Whitaker, and Robert Duvall. 90% of this film was shot in around Auburn, CA in 1995. Some of the locations include the Gold Country Fairgrounds, Machado’s Orchards, and various businesses in Old Town Auburn. -

Children's Television in Asia : an Overview

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Children's television in Asia : an overview Valbuena, Victor T 1991 Valbuena, V. T. (1991). Children's television in Asia : an overview. In AMIC ICC Seminar on Children and Television : Cipanas, September 11‑13, 1991. Singapore: Asian Mass Communiction Research & Information Centre. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/93067 Downloaded on 23 Sep 2021 22:26:31 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Children's Television In Asia : An Overview By Victor Valbuena CHILDREN'ATTENTION: ThSe S inTELEVISIONgapore Copyright Act apIpNlie s tASIAo the use: o f thiAs dNo cumOVERVIEent. NanyangW T echnological University Library Victor T. Valbuena, Ph.D. Senior Programme Specialist Asian Mass Communication Research and Information Centre Presented at the ICC - AMIC - ICWF Seminar on Children and Television Cipanas, West Java, Indonesia 11-13 September, 1991 CHILDREN'S TELEVISION IN ASIA: AN OVERVIEW Victor T. Valbuena The objective of this paper is to present an overview of children's AtelevisioTTENTION: The Snin gaiponre CAsiopyrigaht Aanct apdpl iessom to thee u seo off t histh doceu meproblemnt. Nanyang Tsec hnanologdic al issueUniversity sLib rary that beset it . By "children's television" is meant the range of programme materials made available specifically for children — from pure entertainment like televised popular games and musical shows to cartoon animation, comedies, news, cultural perform ances, documentaries, specially made children's dramas, science programmes, and educational enrichment programmes — and trans mitted during time slots designated for children. -

Jim Henson's Fantastic World

Jim Henson’s Fantastic World A Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department Produced in conjunction with Jim Henson’s Fantastic World, an exhibition organized by The Jim Henson Legacy and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service. The exhibition was made possible by The Biography Channel with additional support from The Jane Henson Foundation and Cheryl Henson. Jim Henson’s Fantastic World Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department, 2009 1 Table of Contents Introduction to Teachers ............................................................................................... 3 Jim Henson: A Biography ............................................................................................... 4 Text Panels from Exhibition ........................................................................................... 7 Key Characters and Project Descriptions ........................................................................ 15 Pre Visit Activities:.......................................................................................................... 32 Elementary Middle High School Museum Activities: ........................................................................................................ 37 Elementary Middle/High School Post Visit Activities: ....................................................................................................... 68 Elementary Middle/High School Jim Henson: A Chronology ............................................................................................