Doing Business in Malaysia: 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Jul 1

The Fifth Estate Broadcasting Jul 1 You'll find more women watching Good Company than all other programs combined: Company 'Monday - Friday 3 -4 PM 60% Women 18 -49 55% Total Women Nielsen, DMA, May, 1985 Subject to limitations of survey KSTP -TV Minneapoliso St. Paul [u nunc m' h5 TP t 5 c e! (612) 646 -5555, or your nearest Petry office Z119£ 1V ll3MXVW SO4ii 9016 ZZI W00b svs-lnv SS/ADN >IMP 49£71 ZI19£ It's hours past dinner and a young child hasn't been seen since he left the playground around noon. Because this nightmare is a very real problem .. When a child is missing, it is the most emotionally exhausting experience a family may ever face. To help parents take action if this tragedy should ever occur, WKJF -AM and WKJF -FM organized a program to provide the most precise child identification possible. These Fetzer radio stations contacted a local video movie dealer and the Cadillac area Jaycees to create video prints of each participating child as the youngster talked and moved. Afterwards, area law enforce- ment agencies were given the video tape for their permanent files. WKJF -AM/FM organized and publicized the program, the Jaycees donated man- power, and the video movie dealer donated the taping services-all absolutely free to the families. The child video print program enjoyed area -wide participation and is scheduled for an update. Providing records that give parents a fighting chance in the search for missing youngsters is all a part of the Fetzer tradition of total community involvement. -

Alphabetical Channel Guide 800-355-5668

Miami www.gethotwired.com ALPHABETICAL CHANNEL GUIDE 800-355-5668 Looking for your favorite channel? Our alphabetical channel reference guide makes it easy to find, and you’ll see the packages that include it! Availability of local channels varies by region. Please see your rate sheet for the packages available at your property. Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package 5StarMAX 712 774 Cinemax A&E 95 488 ABC 10 WPLG 10 410 Local Local Local Local ABC Family 62 432 AccuWeather 27 ActionMAX 713 775 Cinemax AMC 84 479 America TeVe WJAN 21 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package American Heroes Channel 112 Animal Planet 61 420 AWE 256 491 AXS TV 493 Azteca America 399 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package Bandamax 625 En Espanol Package Bang U 810 Adult BBC America 51 BBC World 115 Becon WBEC 397 Local Local Local Local beIN Sports 214 502 beIN Sports (en Espanol) 602 En Espanol Package BET 85 499 BET Gospel 114 Big Ten Network 208 458 Bloomberg 222 Boomerang 302 Bravo 77 471 Brazzers TV 811 Adult CanalSur 618 En Espanol Package Cartoon Network 301 433 CBS 4 WFOR 4 404 Local Local Local Local CBS Sports Network 201 459 Centric 106 Chiller 109 CineLatino 630 En Espanol Package Cinemax 710 772 Cinemax Cloo Network 108 CMT 93 CMT Pure Country 94 CNBC 48 473 CNBC World 116 CNN 49 465 CNN en Espanol 617 En Espanol Package CNN International 221 Comedy Central 29 426 Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

TX-NR636 AV RECEIVER Advanced Manual

TX-NR636 AV RECEIVER Advanced Manual CONTENTS AM/FM Radio Receiving Function 2 Using Remote Controller for Playing Music Files 15 TV operation 42 Tuning into a Radio Station 2 About the Remote Controller 15 Blu-ray Disc player/DVD player/DVD recorder Presetting an AM/FM Radio Station 2 Remote Controller Buttons 15 operation 42 Using RDS (European, Australian and Asian models) 3 Icons Displayed during Playback 15 VCR/PVR operation 43 Playing Content from a USB Storage Device 4 Using the Listening Modes 16 Satellite receiver / Cable receiver operation 43 CD player operation 44 Listening to Internet Radio 5 Selecting Listening Mode 16 Cassette tape deck operation 44 About Internet Radio 5 Contents of Listening Modes 17 To operate CEC-compatible components 44 TuneIn 5 Checking the Input Format 19 Pandora®–Getting Started (U.S., Australia and Advanced Settings 20 Advanced Speaker Connection 45 New Zealand only) 6 How to Set 20 Bi-Amping 45 SiriusXM Internet Radio (North American only) 7 1.Input/Output Assign 21 Connecting and Operating Onkyo RI Components 46 Slacker Personal Radio (North American only) 8 2.Speaker Setup 24 About RI Function 46 Registering Other Internet Radios 9 3.Audio Adjust 27 RI Connection and Setting 46 DLNA Music Streaming 11 4.Source Setup 29 iPod/iPhone Operation 47 About DLNA 11 5.Listening Mode Preset 32 Firmware Update 48 Configuring the Windows Media Player 11 6.Miscellaneous 33 About Firmware Update 48 DLNA Playback 11 7.Hardware Setup 33 Updating the Firmware via Network 48 Controlling Remote Playback from a PC 12 8.Remote Controller Setup 39 Updating the Firmware via USB 49 9.Lock Setup 39 Music Streaming from a Shared Folder 13 Troubleshooting 51 Operating Other Components Using Remote About Shared Folder 13 Reference Information 58 Setting PC 13 Controller 40 Playing from a Shared Folder 13 Functions of REMOTE MODE Buttons 40 Programming Remote Control Codes 40 En AM/FM Radio Receiving Function Tuning into stations manually 2. -

QUESTION 20-1/2 Examination of Access Technologies for Broadband Communications

International Telecommunication Union QUESTION 20-1/2 Examination of access technologies for broadband communications ITU-D STUDY GROUP 2 3rd STUDY PERIOD (2002-2006) Report on broadband access technologies eport on broadband access technologies QUESTION 20-1/2 R International Telecommunication Union ITU-D THE STUDY GROUPS OF ITU-D The ITU-D Study Groups were set up in accordance with Resolutions 2 of the World Tele- communication Development Conference (WTDC) held in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1994. For the period 2002-2006, Study Group 1 is entrusted with the study of seven Questions in the field of telecommunication development strategies and policies. Study Group 2 is entrusted with the study of eleven Questions in the field of development and management of telecommunication services and networks. For this period, in order to respond as quickly as possible to the concerns of developing countries, instead of being approved during the WTDC, the output of each Question is published as and when it is ready. For further information: Please contact Ms Alessandra PILERI Telecommunication Development Bureau (BDT) ITU Place des Nations CH-1211 GENEVA 20 Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 730 6698 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 E-mail: [email protected] Free download: www.itu.int/ITU-D/study_groups/index.html Electronic Bookshop of ITU: www.itu.int/publications © ITU 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. International Telecommunication Union QUESTION 20-1/2 Examination of access technologies for broadband communications ITU-D STUDY GROUP 2 3rd STUDY PERIOD (2002-2006) Report on broadband access technologies DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by many volunteers from different Administrations and companies. -

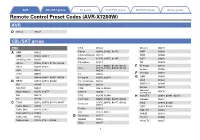

Remote Control Preset Codes (AVR-X7200W) AVR

AVR CBL/SAT group TV group VCR/PVR group BD/DVD group Audio group Remote Control Preset Codes (AVR-X7200W) AVR D Denon 73347 CBL/SAT group CBL CCS 03322 Director 00476 A ABN 03322 Celrun 02959, 03196, 03442 DMT 03036 ADB 01927, 02254 Channel Master 03118 DSD 03340 Alcatel-Lucent 02901 Charter 01376, 01877, 02187 DST 03389 Amino 01602, 01481, 01822, 02482 Chunghwa 01917 DV 02979 Arion 03034, 03336 01877, 00858, 01982, 02345, E Echostar 03452 Cisco 02378, 02563, 03028, 03265, Arris 02187 03294 Entone 02302 AT&T 00858 CJ 03322 F Freebox 01976 au 03444, 03445, 03485, 03534 CJ Digital 02693, 02979 G GBN 03407 B BBTV 02516, 02518, 02980 CJ HelloVision 03322 GCS 03322 Bell 01998 ClubInternet 02132 GDCATV 02980 BIG.BOX 03465 CMB 02979, 03389 Gehua 00476 General Bright House 01376, 01877 CMBTV 03498 Instrument 00476 BSI 02979 CNS 02350, 02980 H Hana TV 02681, 02881, 02959 BT 02294 Com Hem 00660, 01666, 02015, 02832 Handan 03524 C C&M 02962, 02979, 03319, 03407 01376, 00476, 01877, 01982, HCN 02979, 03340 Comcast 02187 Cable Magico 03035 HDT 02959, 03465 Coship 03318 Cable One 01376, 01877 Hello TV 03322 Cox 01376, 01877 Cable&Wireless 01068 HelloD 02979 Daeryung 01877 Cablecom 01582 D Hi-DTV 03500 DASAN 02683 Cablevision 01376, 01877, 03336 Hikari TV 03237 Digeo 02187 1 AVR CBL/SAT group TV group VCR/PVR group BD/DVD group Audio group Homecast 02977, 02979, 03389 02692, 02979, 03196, 03340, 01982, 02703, 02752, 03474, L LG 03389, 03406, 03407, 03500 Panasonic 03475 Huawei 01991 LG U+ 02682, 03196 Philips 01582, 02174, 02294 00660, 01981, 01983, -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

Telecommunications Provider Locator

Telecommunications Provider Locator Industry Analysis & Technology Division Wireline Competition Bureau February 2003 This report is available for reference in the FCC’s Information Center at 445 12th Street, S.W., Courtyard Level. Copies may be purchased by calling Qualex International, Portals II, 445 12th Street SW, Room CY- B402, Washington, D.C. 20554, telephone 202-863-2893, facsimile 202-863-2898, or via e-mail [email protected]. This report can be downloaded and interactively searched on the FCC-State Link Internet site at www.fcc.gov/wcb/iatd/locator.html. Telecommunications Provider Locator This report lists the contact information and the types of services sold by 5,364 telecommunications providers. The last report was released November 27, 2001.1 All information in this report is drawn from providers’ April 1, 2002, filing of the Telecommunications Reporting Worksheet (FCC Form 499-A).2 This report can be used by customers to identify and locate telecommunications providers, by telecommunications providers to identify and locate others in the industry, and by equipment vendors to identify potential customers. Virtually all providers of telecommunications must file FCC Form 499-A each year.3 These forms are not filed with the FCC but rather with the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), which serves as the data collection agent. Information from filings received after November 22, 2002, and from filings that were incomplete has been excluded from the tables. Although many telecommunications providers offer an extensive menu of services, each filer is asked on Line 105 of FCC Form 499-A to select the single category that best describes its telecommunications business. -

IPR 2019 MCMC.Pdf

STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS In accordance with Part V, Chapter 15, Sections 123 – 125 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998, and Part II, Section 6 of Postal Services Act 2012, Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission hereby publishes and has transmitted to the Minister of Communications and Multimedia a copy of this Industry Performance Report (IPR) for the year ended 31 December 2019. MALAYSIAN COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA COMMISSION, 2020 The information or material in this publication is protected under copyright and save where otherwise stated, may be reproduced for non-commercial use provided it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. Where any material is reproduced, MCMC as the source of the material must be identified and the copyright status acknowledged. The permission to reproduce does not extend to any information or material the copyright of which belongs to any other person, organisation or third party. Authorisation or permission to reproduce such information or material must be obtained from the copyright holders concerned. This work is based on sources believed to be reliable, but MCMC does not warrant the accuracy or completeness of any information for any purpose and cannot accept responsibility for any error or omission. Published by: Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission MCMC Tower 1 Jalan Impact Cyber 6 63000 Cyberjaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan T: +60 3 86 88 80 00 F: +60 3 86 88 10 00 Toll Free: 1-800-888-030 W: www.mcmc.gov.my ISSN 1823 – 3724 Note: Numbers and percentages may not add up due to rounding practices. Information and figures given are accurate as per current date and time report was produced. -

Biomedicine and Makeover TV DISSERTATION

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Bio-logics of Bodily Transformation: Biomedicine and Makeover TV DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Visual Studies by Corella Ann Di Fede Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Lucas Hilderbrand, Chair Associate Professor Fatimah Tobing Rony Associate Professor Jennifer Terry Assistant Professor Allison Perlman 2016 © 2016 Corella Ann Di Fede DEDICATION To William Joseph Di Fede, My brother, best friend and the finest interlocutor I will ever have had. He was the twin of my own heart and mind, and I am not whole without him. My mother for her strength, courage and patience, and for her imagination and curiosity, My father whose sense of humor taught me to think critically and articulate myself with flare, And both of them for their support, generosity, open-mindedness, and the care they have taken in the world to live ethically, value every life equally, and instill that in their children. And, to my Texan and Sicilian ancestors for lending me a history full of wild, defiant spirits ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vii INTRODUCTION 1 Biopolitical Governance in Pop Culture: Neoliberalism, Biomedicine, and TV Format 3 Health: Medicine, Morality, Aesthetics and Political Futures 11 Biomedicalization, the Norm, and the Ideal Body 15 Consumer-patient, Privatization and Commercialization of Life 20 Television 24 Biomedicalized Regulation: Biopolitics and the Norm 26 Emerging -

Download Content (PDF)

CONTENT CONTENT RAISING THE BAR of Asian content with compelling vernacular originals that capture customers’ hearts INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2019 101 CONTENT 2018 was a huge year for our movies as our films collectively grossed over RM100 million in local cinemas We continue to captivate viewers’ imagination through our Box office champion comprehensive and eclectic content spread underpinned by our Our movies led the way in FY19, grossing over RM100 million in key differentiator – our own signature vernacular IPs. We produced local cinemas. With 9% share of overall Malaysia GBO collection and commissioned over 12,600 hours of content serving our (comprising international and local releases) and over 60% share of demographically diverse customers across varied ethnic groups who local movies’ GBO collection, this represents our best performance speak various languages and dialects. to date. The simplicity of the narratives yet profound subject matters resonated well among with diverse audiences while uniting Overall viewership has increased in FY19 through the combination Malaysians at the cinemas. of linear, OD and OTT. Linear viewership, measured as TV viewership share remained resilient at 75%, supplemented by growing OD Our highest grossing movie ever, satirical horror movie Hantu Kak consumption as video downloads more than doubled to 54 million Limah was miles ahead of most major Hollywood franchise titles and OTT registered users increased 32% to 2.2 million. released in Malaysia in 2018, raking in RM38 million. Our top performing action flick, Paskal reignited the sense of patriotism Our movies have done exceptionally well in FY19 by setting new among Malaysians and collected RM30 million in ticket sales. -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C.