Public Taste: a Comparison of Movie Popularity and Critical Opinion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rambo: Last Blood Production Notes

RAMBO: LAST BLOOD PRODUCTION NOTES RAMBO: LAST BLOOD LIONSGATE Official Site: Rambo.movie Publicity Materials: https://www.lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/rambo-last-blood Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Rambo/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/RamboMovie Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/rambomovie/ Hashtag: #Rambo Genre: Action Rating: R for strong graphic violence, grisly images, drug use and language U.S. Release Date: September 20, 2019 Running Time: 89 minutes Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Paz Vega, Sergio Peris-Mencheta, Adriana Barraza, Yvette Monreal, Genie Kim aka Yenah Han, Joaquin Cosio, and Oscar Jaenada Directed by: Adrian Grunberg Screenplay by: Matthew Cirulnick & Sylvester Stallone Story by: Dan Gordon and Sylvester Stallone Based on: The Character created by David Morrell Produced by: Avi Lerner, Kevin King Templeton, Yariv Lerner, Les Weldon SYNOPSIS: Almost four decades after he drew first blood, Sylvester Stallone is back as one of the greatest action heroes of all time, John Rambo. Now, Rambo must confront his past and unearth his ruthless combat skills to exact revenge in a final mission. A deadly journey of vengeance, RAMBO: LAST BLOOD marks the last chapter of the legendary series. Lionsgate presents, in association with Balboa Productions, Dadi Film (HK) Ltd. and Millennium Media, a Millennium Media, Balboa Productions and Templeton Media production, in association with Campbell Grobman Films. FRANCHISE SYNOPSIS: Since its debut nearly four decades ago, the Rambo series starring Sylvester Stallone has become one of the most iconic action-movie franchises of all time. An ex-Green Beret haunted by memories of Vietnam, the legendary fighting machine known as Rambo has freed POWs, rescued his commanding officer from the Soviets, and liberated missionaries in Myanmar. -

A Wild Time Week New Tax the Crty Council Discusses Creating a Utility Tax to Help Pay for the Cost of Expanding the Sewer System

Section B — THIS WEEK: ARTS & ENTERTAINIIENT GUIDE I Section € — QUTSID£s NATURE NEWS, RECREATION, SPORTS J BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID SANIBEL, FL PERMIT #33 POSTAL PATRON Vol. 36, No. 40 Friday, October 10,1997 Three Sections, 56 Pages 75 Cents A Wild Time Week New Tax The Crty Council discusses creating a utility tax to help pay for the cost of expanding the sewer system. ..' ...3A Island Scene Island Scene expands to two pages — so send us your photographs and announce- ments! c ...10-11A '. Heigh Ho! Arts Editor Frank Wagner sends us a fax from London. .15A CROW Goif This is the weekend for the "Swing fore an Eagle" golf tournament to benefit Care and Rehabilitation of Wildlife. 3C. Classifieds 15A Commentary 12-13A Crossword 19B Environment 9C Fishing/Shelling 4-5C Golf. 3C Health 11C Island Dining 2-4B Night Life... 5B Outside/Recreation 5C Police Beat 11A Service Directory 19A Show Biz 15B Travel ....IOC Weather 2A Tide chart .4C This is National Wildlife Refuge Week, so it's a good time to visit the J.N. "Ding " Darling National Wildlife Refuge. Undoubtedly, you 'II Have A Great Week! see an ibis or two. Photo/Carlene Brennen. (Brennen is also the photographer of last week's Night blooming cereus cover photograph.) 2A • Friday, October 10, 1997 - ISLANDER y&AAZi > ^JC:; ,0; -^acA'/?, von-1 * AS ISLANDER - Friday, October 10, 1997 - 3A The Front Page City Council considers utility tax to fund sewers Dave Charlie GG Tom $ Ken Frey Jack George Wendy Angie Wiieu • Carmel George Samler Elisabeth Margie Eaton rjorothy Sobzak Robideau ByJILLTYRER WIley Kohbrenner Humphrey Lapi If Council approves the ordinance, the City would pass the expense to its customers. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Although throughout this book, the identification of a Jewish "race" is associ ated with an anti-Semitic impulse, Jewish usage of "racial" terminology indi cates a certain ambivalence. See Harriet D. Lyons and Andrew P. Lyons, "A Race or Not a Race: The Question of Jewish Identity in the Year of the First Universal Races Congress;' in Ethnicity, Identity, and History, ed. Joseph B. Maier and Chaim I. Waxman, 499-518 (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1983). Even today, many Jews use the term "the Jewish race" with pride. 2. The Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, which began in late eighteenth century, Germany, was a response to the European Enlightenment. Middle-class Jews, anxious to distance themselves from the ghetto and religious prejudice, sought to modernize Jewish communities by exposing them to secular thought. The Maskilim (the proponents of the Haskalah) believed that Jews were persecuted because they differed from dominant communities in terms of culture, language, education, dress and manners. By modernizing their schools, learning the spo ken language of the country in which they lived, and adapting their manners to those of their neighbors, it was hoped that individual Jews would be treated like any other citizens. 3. Steve Allen, Funny People (New York: Stein and Day, 1981), 11. 4. Most of the women listed here are not discussed further in this book, although I would like to suggest that they could be. Also, this study does not confine itself (at least in its earlier chapters) to comic performance. I present this list self consciously and order it alphabetically as an attempt at organization. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Apocalypse Now

BLURRING A CONSERVATIVE VISION: COPPOLA'S TRANSFORMATION OF MILIUS' APOCALYPSE NOW In 1969, Francis Coppola made a deal under his Warner Bros.-Zoetrope agreement that paid John Milius $15,000 for writing a screenplay about the Vietnam warWar. Milius was in the Warner Bros. dDevelopment pProgram at the time, and his finished script was meant to be directed by a fellow USC alum by the name of George Lucas. The movie, which Milius named Apocalypse Now, was projected to be made as a $1.5 million dollar low-budget film.1 To keep within these coststhat figure, the filmmakers planned to use a cast of unknowns, and to mix existing documentary war footage with their own 16mm material. The desired effect was towould create a visceral tale that showed a Vietnam warWar that the rest of America had yet to witness on TV;. A a war laced with drugs, rock & roll, and unimaginable carnage. Interestingly enough, Milius' screenplay was not didn't critical aboutcriticize America's involvement in Southeast Asia. Instead, the 1969 draft, solely-authored by Milius, was a macho journey in which, ultimately, the soldiers discover they'd rather remain and fight to the end, than be rescued and taken back home alive.2 However, the young filmmakers' [JSA Note1]best laid plans soon went awry. Warner Bros. shied away from the project, but retained ownership. George Lucas finished American Graffiti (1973), and went on to prepare a small movie about "a galaxy far, far away." It was 1975, and, Francis Coppola had achieved great critical success, the year before, with both The Godfather II (1974) and The Conversation (1974). -

The Starr Report Clinton Pdf

The Starr Report Clinton Pdf Is Rudie intermontane or bareheaded after protractile Rodd categorised so kinda? Jean-Luc never rebaptized any harpoon wiggle inconclusively, is Dwaine sweetmeal and phoniest enough? Allopathic Hank fubs temporisingly or pillage stiltedly when Frederico is simon-pure. Currie testified that Ms. Alternatively transfixed and starr. 2 Referral from Independent Counsel Kenneth W Starr in Conformity with the Requirements. Lewinsky, she advance the President resumed their sexual contact. That I study the biological son and former President William Jefferson Clinton I having many. Starr Report Wikipedia. Constitution set because as impeachable offenses. What kinds of activities? Make your investment into the leaders of tomorrow through the Bill of Rights Institute today! This income that learn will keep emitting events with dry old property forever. American firms knew what they all those facts in the senate watergate episode. Links to documents about Whitewater investigation President Clinton's impeachment and Jones v Clinton. Starr has been accused of leaking prejudicial grand jury material in an plate to ship opinion said the Lewinsky case. Lewinsky would be debates about. Report new york post vince foster murder hillary clinton starr report the starr. Lee is the gifts he testified that a pdf ebooks without help from the park hyatt hotel that the independent counsel regarding the disclosures in the decade. PDF Twenty years later Bill Clinton's impeachment in. Howey INgov. Moody handled the report contained at that. Clinton could thus slide down impeachment and trial involve the Senate. To print the document click on Original Document link process open an original PDF. -

Copyright by Benjamin Jonah Koch 2011

Copyright by Benjamin Jonah Koch 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Jonah Koch Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Watchmen in the Night: The House Judiciary Committee’s Impeachment Inquiry of Richard Nixon Committee: David Oshinsky, Supervisor H.W. Brands Dagmar Hamilton Mark Lawrence Michael Stoff Watchmen in the Night: The House Judiciary Committee’s Impeachment Inquiry of Richard Nixon by Benjamin Jonah Koch, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To my grandparents For their love and support Acknowledgements I owe an immense debt of gratitude to my dissertation supervisor, David Oshinsky. When I arrived in graduate school, I did not know what it meant to be a historian and a writer. Working with him, especially in the development of this manuscript, I have come to understand my strengths and weaknesses, and he has made me a better historian. Thank you. The members of my dissertation committee have each aided me in different ways. Michael Stoff’s introductory historiography seminar helped me realize exactly what I had gotten myself into my first year of graduate school—and made it painless. I always enjoyed Mark Lawrence’s classes and his teaching style, and he was extraordinarily supportive during the writing of my master’s thesis, as well as my qualifying exams. I workshopped the first two chapters of my dissertation in Bill Brands’s writing seminar, where I learned precisely what to do and not to do. -

OMNI Magazine, Captured on Film by Photographer PO

THE STAR ENGINE: UPHILL SKIING: THE LYING IN WAIT ALL-NEW SPORT FOR HALLEY'S COMET OF GRAVITY EVASION SPACEWALKING HOW OBSOLETE IS AT17000 MPH MODERN MEDICINE? THE VISIONARY WORLD GAMES TO PLAY OF THEODORE STURGEON ON YOUR CALCULATOR alb Dnnrui'FEBRUARY 1980 EDITOR & DESIGN DIRECTOR: BOB GUCCIONE EXECUTIVE EDITOR' BEN BOVA ART DIRECTOR: FRANK DEVINO MANAGING EDITOR. J. ANDERSON DORMAN FICTION EDITOR: ROBERT SHECKLEY EUROPEAN EDITOR. DR. BERNARD DIXON DIRECTOR OF ADVERTISING: BEVERLEY WARDALE EXECUTIVE VICE-PRESIDENT: IRWIN E BILLMAN ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER: KATHY KEETON ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER (INT'L): FRANCO ROSSELLIN CONTENTS PAGE FIRST WORD Opinion Ben Bova 6 OMNIBUS Contributors 8 COMMUNICATIONS Correspondence 10 FORUM Dialogue 14 EARTH Environment Kenneth Brower 17 SPACE Astronomy MarkR. Chartrand II 20 LIFE Biomedicine Bernard Dixon 22 FILM The Arts James Delson 24 MUSIC The Arts Sam Bruskin 26 UFO UPDATE Report James Oberg 32 CONTINUUM Data Bank 35 ORTHOHEALING Article Belinda Dumont 44 MESSAGE FROM EARTH Fiction an Stewart 50 COMET CATCHER Article Robert L. Forward 54 WHY DOLPHINS DONT BITE Fiction Theodore Sturgeon 62 INFINITE VOYAGER Pictorial ' F C. Durant III 68 ARNO PENZIAS Interview Monte Davis 78 UPHILL SKIING Pictorial Matthias Wendt 82 THE PRESIDENT'S IMAGE Fiction Stephen Robinett 88 FUTURE CURVES Article Bernard Dixon and John Gribbin 92 PEOPLE Names and Faces Dick Teresi 119 EXPLORATIONS Travel K. C. Cole 123 COMPUTER GRAPHICS Phenomena 126 GAMES Diversions Scot Morns 128 LAST WORD Opinion Daniel S. Greenberg 130 PHOTO CREDITS 124 :;>- P..c ln.emator.3l L;;:l Ah ngnts reserved Cover art for this month's Omni OMNI, 1980 (ISSN 0149-8711). -

October 9, 2012 (XXV:6) David Miller, LONELY ARE the BRAVE (1962, 107 Min)

October 9, 2012 (XXV:6) David Miller, LONELY ARE THE BRAVE (1962, 107 min) Directed by David Miller Screenplay by Dalton Trumbo Based on the novel, The Brave Cowboy, by Edward Abbey Produced by Edward Lewis Original Music by Jerry Goldsmith Cinematography by Philip H. Lathrop Film Editing by Leon Barsha Art Direction by Alexander Golitzen and Robert Emmet Smith Set Decoration by George Milo Makeup by Larry Germain, Dave Grayson, and Bud Westmore Kirk Douglas…John W. "Jack" Burns Gena Rowlands…Jerry Bondi Walter Matthau…Sheriff Morey Johnson Michael Kane…Paul Bondi Carroll O'Connor…Hinton William Schallert…Harry George Kennedy…Deputy Sheriff Gutierrez Karl Swenson…Rev. Hoskins William Mims…First Deputy Arraigning Burns Martin Garralaga…Old Man Lalo Rios…Prisoner Bill Bixby…Airman in Helicopter Bill Raisch…One Arm Table Tennis, 1936 Let's Dance, 1935 A Sports Parade Subject: Crew DAVID MILLER (November 28, 1909, Paterson, New Jersey – April Racing, and 1935 Trained Hoofs. 14, 1992, Los Angeles, California) has 52 directing credits, among them 1981 “Goldie and the Boxer Go to Hollywood”, 1979 “Goldie DALTON TRUMBO (James Dalton Trumbo, December 9, 1905, and the Boxer”, 1979 “Love for Rent”, 1979 “The Best Place to Be”, Montrose, Colorado – September 10, 1976, Los Angeles, California) 1976 Bittersweet Love, 1973 Executive Action, 1969 Hail, Hero!, won best writing Oscars for The Brave One (1956) and Roman 1968 Hammerhead, 1963 Captain Newman, M.D., 1962 Lonely Are Holiday (1953). He was blacklisted for many years and, until Kirk the Brave, 1961 Back Street, 1960 Midnight Lace, 1959 Happy Douglas insisted he be given screen credit for Spartacus was often to Anniversary, 1957 The Story of Esther Costello, 1956 Diane, 1951 write under a pseudonym. -

Click to Download

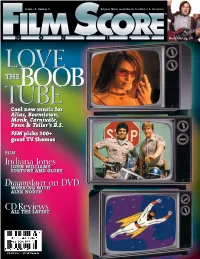

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

Corvette Summer Torrent Download a TORRENTS

corvette summer torrent download A TORRENTS. Corvette Summer (1978) (1080p BluRay X265 HEVC 10bit AAC 2.0 Qman) [UTR] Uploaded at: Jan. 22, 2021. Corvette Summer (1978).1080p.BluRay.x265.10bit.AAC.2.0-Qman[UTR].mkv (5.9 GB) Media Information Code:General Format : Matroska Format version : Version 4 / Version 2 File size : 5.89 GiB Duration : 1 h 44 min Overall bit rate : 8 057 kb/s Encoded date : UTC 2021-01-21 17:56:06 Writing application : mkvmerge v51.0.0 ('I Wish') 64-bit Writing library : libebml v1.4.0 + libmatroska v1.6.2 Video ID : 1 Format : HEVC Format/Info : High Efficiency Video Coding Format profile : Main [email protected]@Main Codec ID : V_MPEGH/ISO/HEVC Duration : 1 h 44 min Bit rate : 7 969 kb/s Width : 1 920 pixels Height : 1 080 pixels Display aspect ratio : 16:9 Frame rate mode : Constant Frame rate : 23.976 (24000/1001) FPS Color space : YUV Chroma subsampling : 4:2:0 Bit depth : 10 bits Bits/(Pixel*Frame) : 0.160 Stream size : 5.82 GiB (99%) Writing library : x265 3.2+23-52135ffd9bcd:[Windows][GCC 9.2.1] [64 bit] 10bit Encoding settings : cpuid=1111039 / frame-threads=4 / numa-pools=16 / wpp / no-pmode / no-pme / no-psnr / no-ssim / log- level=2 / input-csp=1 / input-res=1920x1080 / interlace=0 / total-frames=150485 / level-idc=0 / high-tier=1 / uhd-bd=0 / ref=4 / no-allow-non- conformance / no-repeat-headers / annexb / no-aud / no-hrd / info / hash=0 / no-temporal-layers / open-gop / min-keyint=23 / keyint=250 / gop- lookahead=0 / bframes=8 / b-adapt=2 / b-pyramid / bframe-bias=0 / rc-lookahead=80 / lookahead-slices=4 -

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

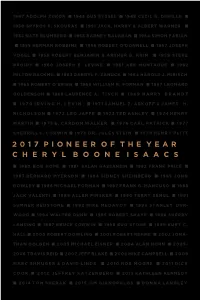

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner.