Folia Orient. Bibliotheca I.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet(5 December 1820 - 3 December 1892) Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet, later changed his name to Shenshin was a Russian poet regarded as one of the finest lyricists in Russian literature. <b>Biography</b> <b>Origins</b> The circumstances of Afanasy Fet's birth have been the subject of controversy, and some uncertainties still remain. Even the exact date is unknown and has been cited as either October 29 (old style), or November 23 or 29, 1820. Brief biographies usually maintain that Fet was the son of the Russian landlord Shenshin and a German woman named Charlotta Becker, an that at the age of 14 he had to change his surname from his father's to that of Fet, because the marriage of Shenshin and Becker, registered in Germany, was deemed legally void in Russia. Detailed studies reveal a complicated and controversial story. It began in September 1820 when a respectable 44-year old landlord from Mtsensk, Afanasy Neofitovich Shenshin, (described as a follower of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's ideas) returned to his Novosyolky estate from the German spa resorts where he had spent a year on a recreational trip. There he had rented rooms in the house of Karl Becker and fell for his daughter Charlotta Elizabeth, a married woman with a one-year-old daughter named Carolina, and pregnant with another child. As to what happened next, opinions vary. According to some sources. Charlotta hastily divorced her husband Johann Foeth, a Darmstadt court official, others maintain that Shenshin approached Karl Becker with the idea that the latter should help his daughter divorce Johann, and when the old man refused to cooperate, kidnapped his beloved (with her total consent). -

SUMMARY Articles and Reports History of Literature Natalia L

SUMMARY Articles and Reports History of Literature Natalia L. Lavrova. The motif of Divine Narcissism in Baroque Literature. This article focuses on historical fate of the motif of divine narcissism which is explicitly actualized in Baroque literature. Key words: Narcissus myth; Baroque; divine narcissism; «Divine Comedy»; Ficino; «Paradise Lost». Olga A. Bogdanova. «Country-estate Culture» in the Russian Literature of the XIX – beg. XX Century. Social and Cultural Aspects. The country estate of the XIX century as a phenomenon of Russian culture united the parts of the Russian nation – nobility and peasantry, split in the process of Peter’s reforms – into a certain wholeness. Both Europeism and «soilness» of the Russian classical literature came from the fact that its creators, the Russian landlords with their European education, within the estate were closely tied with the peasants and thus could express the folk mentality by the European artistic language. The town intellectuals of the «Silver Age», alien to the «country-estate culture», on the opposite, lost the immediate link with the common people and created the literature, which was far from the national religious tradition («legend»), not that of «soil», but of «catastrophy». Key words Country-estate; estate nobility; peasantry; Russian classical literature; «legend»; intellectuals; Silver Age; «soillessness»; catastrophism. Yulia N. Starodubtseva. Afanasy Fet’s Works as Perceived by Aleksandr Blok (using Aleksandr Blok’s library as a study case). The author aims to investigate the influence of Afanasy Fet’s work on Aleksandr Blok by analyzing the notes made by Blok when reading. This method makes it possible to address the issue on the basis of factual and therefore more reliable material, and pairing poems for comparison is facilitated by the fact that Fet’s side is preselected by Blok’s notes. -

Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes in the Context of Symbolism Andrey Konovalov1,A Liudmila Mikheeva2,* Yulia Gushchina3,B

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 572 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2021) Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes in the Context of Symbolism Andrey Konovalov1,a Liudmila Mikheeva2,* Yulia Gushchina3,b 1 Institute of Fine Arts, Moscow Pedagogical State University, Moscow, Russia 2 Department of General Humanitarian Disciplines, Russian State Specialized Academy of Arts, Moscow, Russia 3 Likhachev Russian Research Institute for Cultural and Natural Heritage, Moscow, Russia a Email: [email protected] b Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The present article focuses on the artistic culture of the Silver Age and the remarkable creative atmosphere of Russia at the turn of the 20th century characterized by the synthesis of arts: drama, opera, ballet, and scenography. A key figure of the period was Sergei Diaghilev, the editor and publisher of the magazines Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) and The Yearbook of the Imperial Theatres, the founder of the famous Ballets Russes in Paris, the organizer of exhibitions of Russian artists of different schools and movements. The article studies the features of Symbolism as an artistic movement and philosophy of art of the Silver Age, a spiritual quest of artistic people of the time, and related and divergent interests of representatives of different schools and trends. The Silver Age is considered the most sophisticated and creative period of Russian culture, the time of efflorescence, human spirit, creativity, the rise of social forces, general renewal, in other words, Russian spiritual and cultural renaissance. -

Translation of Selected Poems by K. Balmont

Swarthmore College Works Russian Faculty Works Russian 2015 Translation Of Selected Poems By K. Balmont K. Balmont Sibelan E.S. Forrester Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian Part of the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation K. Balmont and Sibelan E.S. Forrester. (2015). "Translation Of Selected Poems By K. Balmont". Russian Silver Age Poetry. 33-37. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian/220 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Konstantin Balmont 33 became more demanding; his poetry was described as a magnificent transla- tion from an unknown original, though always praised for its musicality. He himself translated poetry from numerous languages; authors he rendered from English included Blake, Poe, Shelley, Whitman, and Wilde. Balmont emigrated to France in 1922 and lived there in poverty, as did most émigré poets; he suffered a gradual mental decline that limited his ability to write and died in 1942. Verblessness [Безглагольность] In the nature of Russia there’s some weary tenderness, The unspeaking pain of a deep-buried sorrow, Ineluctable grief, voicelessness, endlessness, A high frozen sky, and horizons unfolding. Come out here at dawn to the slope of the hillside— A chill smoking over the shivering river, The massive pine forest stands darkly, unmoving, And the heart feels such pain, and the heart is not gladdened. -

Golden Age of Russian Literature New York - Washington 03-15 October 2015

Golden Age of Russian Literature New York - Washington 03-15 October 2015 ARTISTTV EXPO EXHIBITION in USA 3 2 Representatives of the Shaliapin music school with school director Irina Strykava Opera singer Irina Velichko Tenor Aleksaandr Lesin Memorable photo for memory participants of the concert «Cover girl» Superior room in the main building of the Russian Foreign Ministry on Smolenksoy Square opened its doors to the exhibition «Golden Age» of Russian literature» in Moscow from 16-24 september 2015 At the opening were well-known artists Irina Velichko and Alexander Lesin that sangs opera Speech by the deputy Department for songs. Culture of the Russian Foreign Ministry Ivanov Aleksey Vladimirovich Teachers and the best students of the director and organizer ARTISTTV Shalapin music school Moscow played and Yurchenko Andrey Anatolyevich sang for visitors. Curator Julia Jurchenko and Olga Mironovna Zinovieva - the wife of Alexander painter Svetlana Malahova Zinoviev, companion, guardian of the creative and intellectual heritage of Alexander Alexandrovich Zinoviev, the world-famous Russian thinker, On cover philosopher, logic, sociologist, writer and citizen. picture Andrei Podgorny «Sprout» Dear friends ! This booklet is catalogue , but has been designed to study. It get not For over a year, the project «Golden Age» of Russian literature» only the contemporary art culture of Russia, but also to learn the walking on the world. We make exhibition in different countries cultural origins of the Russian culture of the 19th century. and cities, and everywhere we were met with great success. Poems, sayings , citation of great writers - are selected in such a Of course this is due to the large interest in the theme of way that the reader knew what most deeply influence to Russian exhibition. -

London International Antiquarian Book Fair June 1-3, 2017 the Olympia National Hall 2017

Stand F14 LONDON INTERNATIONAL ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR June 1-3, 2017 The Olympia National Hall 2017 LONDON LONDON INTERNATIONAL ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR The Olympia National Hall 2017 Visit us at Stand F14 June 1-3, 2017 The Olympia National Hall Hammersmith Road, London W14 8UX LONDON Thursday 1st June: 1pm–8pm Friday 2nd June: 11am–7pm Saturday 3rd June: 11am–4pm Images and more information available on request. The prices are in £. Shipping costs are no included. We accept wire transfer and PayPal. Cover and pages design with details from our books in this list. Dickens in woodcuts 1. Dickens Charles Sverchok na pechi [The Cricket on the Hearth]. [Translation by M. Shishmareva]. Cover and illustrations by A. Kravchenko Moskva-Leningrad, Gosudarstvennoe izdatelʹstvo, 1925. 16mo, 143, [1] pp., ill. In publisher’s illustrated wrappers Near very good condition Limited to 4 000 copies. Fine illustrated edition of The Cricket on the Hearth (1845) in Russian. For the first time this translation appeared in Dickens’s Collected works (St. Petersburg, vol. 7, 1894). Our edition doesn’t contain the translator’s name. Cover, headpieces, endpieces and five full-page woodcuts by graphic artist Aleksey Kravchenko (1889–1940). He is considered a master of woodcut. He studied at Simon Hollosy’s art school in Munich and at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture under Konstantin Korovin and Valentin Serov. He was a member of the Four Arts Society of Artists. For the first time Russian artists illustrated Dickens’ works in the end of the XIX century. In the 20s of the XX century new generation of the Russian graphic artists, avant-garde minds, came back to Dickens and prepared illustrated editions of Great ex- pectations (Mitrokhin and Budogoskii, 1929 and 1935), Hard times (Favorsky, 1933), The posthumous papers of the Pickwick club (Milashevsky 1933). -

Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial Board T

GUIDE Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial board T. Liptuga, G. Zakipnaya, G. Semykina, A. Yavorskaya Authors A. Yavorskaya, G. Semykina, Y. Karakina, G. Zakipnaya, L. Melnichenko, A. Bozhko, L. Liputa, M. Kotelnikova, I. Savrasova English translation O. Voronina Photo Georgiy Isayev, Leonid Sidorsky, Andrei Rafael О417 Одеський літературний музей : Путівник / О. Яворська та ін. Ред. кол. : Т. Ліптуга та ін., – Фото Г. Ісаєва та ін. – Одеса, 2017. – 160 с.: іл. ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 Odessa Literary Museum: Guide / A.Yavorskaya and others. Editorial: T. Liptuga and others, - Photo by G.Isayev and others. – Odessa, 2017. — 160 p.: Illustrated Guide to the Odessa Literary Museum is a journey of more than two centuries, from the first years of the city’s existence to our days. You will be guided by the writers who were born or lived in Odessa for a while. They created a literary legend about an amazing and unique city that came to life in the exposition of the Odessa Literary Museum UDC 069:801 (477.74) Англійською мовою ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 © OLM, 2017 INTRODUCTION The creators of the museum considered it their goal The open-air exposition "The Garden of Sculptures" to fill the cultural lacuna artificially created by the ideo- with the adjoining "Odessa Courtyard" was a successful logical policy of the Soviet era. Despite the thirty years continuation of the main exposition of the Odessa Literary since the opening day, the exposition as a whole is quite Museum. The idea and its further implementation belongs he foundation of the Odessa Literary Museum was museum of books and local book printing and the history modern. -

Construction and Tradition: the Making of 'First Wave' Russian

Construction and Tradition: The Making of ‘First Wave’ Russian Émigré Identity A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of History from The College of William and Mary by Mary Catherine French Accepted for ____Highest Honors_______________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Frederick C. Corney, Director ________________________________________ Tuska E. Benes ________________________________________ Alexander Prokhorov Williamsburg, VA May 3, 2007 ii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Part One: Looking Outward 13 Part Two: Looking Inward 46 Conclusion 66 Bibliography 69 iii Preface There are many people to acknowledge for their support over the course of this process. First, I would like to thank all members of my examining committee. First, my endless gratitude to Fred Corney for his encouragement, sharp editing, and perceptive questions. Sasha Prokhorov and Tuska Benes were generous enough to serve as additional readers and to share their time and comments. I also thank Laurie Koloski for her suggestions on Romantic Messianism, and her lessons over the years on writing and thinking historically. Tony Anemone provided helpful editorial comments in the very early stages of the project. Finally, I come to those people who sustained me through the emotionally and intellectually draining aspects of this project. My parents have been unstinting in their encouragement and love. I cannot express here how much I owe Erin Alpert— I could not ask for a better sounding board, or a better friend. And to Dan Burke, for his love and his support of my love for history. 1 Introduction: Setting the Stage for Exile The history of communities in exile and their efforts to maintain national identity without belonging to a recognized nation-state is a recurring theme not only in general histories of Europe, but also a significant trend in Russian history. -

Livret Philadelphia

DMITRI HVOROSTOVSKY RACHMANINOV ROMANCES IVARI ILJA, piano SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873–1943) 1 We shall rest ( My otdokhnjom) , Op. 26/3 2’32 2 Do you remember the evening? ( Ty pomnish’ li vecher?) (1893) 2’59 3 Oh no, I beg you, do not leave! ( O, net, molju, ne ukhodi!), Op. 4/1 1’49 4 Morning ( Utro) , Op. 4/2 2’28 5 In the silence of the mysterious night ( V molchan’ji nochi tajnoj) , Op. 4/3 2’51 2 6 Oh you, my corn field! ( Uzh ty, niva moja!) , Op. 4/5 4’47 7 My child, you are beautiful as a flower ( Ditja! Kak cvetok ty prekrasna) , Op. 8/2 2’14 8 A dream ( Son) , Op. 8/5 1’30 9 I was with her ( Ja byl u nej) , Op. 14/4 1’28 10 I am waiting for you (Ja zhdu tebja) , Op. 14/1 1’58 11 Do not believe me, my friend ( Ne ver mne drug) , Op. 14/7 1’41 12 She is as beautiful as noon ( Ona, kak polden’, khorosha) , Op. 14/9 3’05 13 Spring waters (Vesennije vody ), Op. 14/11 2’15 14 In my soul (V mojej dushe) , Op. 14/10 3’08 15 It is time! (Pora!), Op. 14/12 1’58 16 They replied (Oni otvechali) , Op. 21/4 1’58 17 An excerpt from Alfred de Musset ( Otryvok iz A. Mjusse) , Op. 21/6 2’17 18 How nice this place is ( Zdes’ khorosho) , Op. 21/7 2’10 19 How much it hurts (Kak mne bol’no) , Op. -

Concert Program

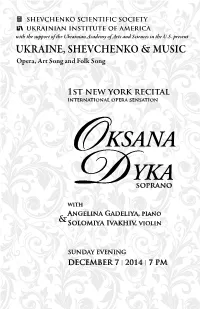

Oksana Dyka, soprano Angelina Gadeliya, piano • Solomiya Ivakhiv, violin I. Bellini Vincenzo Bellini Casta Diva (1801-1835) from Norma (1831) Program Mozart Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro (1756-1791) from The Marriage of Figaro (1786) Rossini Gioachino Rossini Selva opaca, Recitative and Aria (1792-1868) from Guglielmo Tell (William Tell, 1829) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya II. Shchetynsky Alexander Shchetynsky An Episode in the Life of the Poet, (b. 1960) an afterword to the opera Interrupted Letter (2014) World Premiere Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya III. From Poetry to Art Songs 1: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Shtoharenko Andriy Shtoharenko Yakby meni cherevyky (1902-1992) (If I had a pair of shoes, 1939) Silvestrov Valentin Silvestrov Proshchai svite (b. 1937) (Farewell world, from Quiet Songs, 1976) Shamo Ihor Shamo Zakuvala zozulen’ka (1925-1982) (A cuckoo in a verdant grove, 1958) Skoryk Myroslav Skoryk Zatsvila v dolyni (b. 1938) (A guelder-rose burst into bloom, 1962) Mussorgsky Modest Mussorgsky Hopak (1839-1881) from the opera Sorochynsky Fair (1880) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya 2 Program — INTERMISSION — I V. Beethoven Ludwig van Beethoven Allegro vivace (1770-1827) from Sonata in G Major, Op. 30 (1801-1802) Vieuxtemps Henri Vieuxtemps Désespoir (1820-1881) from Romances sans paroles, Op. 7, No. 2 (c.1845) Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya V. From Poetry to Art Songs 2: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Lysenko Mykola Lysenko Oy, odna ya odna (1842-1912) (I’m alone, so alone, 1882) Rachmaninov Sergei Rachmaninov Poliubila ya na pechal’ svoyu, (1873-1943) Op. 8, No. 4 (I have given my love, 1893) Stetsenko Kyrylo Stetsenko Plavai, plavai, lebedon’ko (1882-1922) (Swim on, swim on, dear swan, 1903) Dankevych Konstantyn Dankevych Halia’s Aria (1905-1984) from the opera Nazar Stodolia (1960) VI. -

Wb Yeats and 20Th Century Russian Music

Tyumen State University Herald. Humanities Research. Humanitates, vol. 3, no 2, рр. 101-108 101 Alla V. KONONOVA1 W. B. YEATS AND 20TH CENTURY RUSSIAN MUSIC: NEW AESTHETIC IDEAS AT THE CROSSROADS OF CULTURE 1 Postgraduate Student, Foreign Literature Department, Tyumen State University [email protected] Abstract The article dwells upon the conceptual parallels between one of the greatest Irish poets W. B. Yeats and Russian composers of the 20th century, Alexander Scriabin and Igor Stravinsky. Yeats first became known in Russia in the end of the 19th century. Gradually, his works en- tered the literary context and subsequently opened a new perspective in the critical studies of early 20th century Russian poetry (prominent examples include works by the linguist and anthropologist Vyacheslav Ivanov, the poet and translator Grigory Kruzhkov, and so forth). However, very little attention has been given so far to the intriguing connection between Yeats and his Russian musical contemporaries. Thus, the article focuses on the comparative study of the philosophy and aesthetic principles of W. B. Yeats and the Russian composers, and highlights similarities in their aesthetic systems (such as the idea of time and Hermetic symbolism in the philosophy of Yeats and Alexander Scriabin). The comparative approach allows the author to look at the music of Scriabin and Stravinsky through the prism of poetry and vice versa to view Yeats’s works through the music of his Russian contemporaries. The author also aims to find out how the poet and the composers expressed similar ideas and aesthetic principles using completely different systems — that of music and that of the language. -

Translation, Littérisation, and the Nobel Prize for Literature

TranscUlturAl, vol. 8.1 (2016), 57-75. http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/TC Translation, Littérisation, and the Nobel Prize for Literature Kelly Washbourne Kent State University, USA As I proceed, I will from time to time indicate to you where we are in the manuscript. That way you won’t lose the thread. This will be of help especially to those of you who don’t understand either Italian or Swedish. English speakers will have a tremendous advantage over the rest because they will imagine things I’ve neither said nor thought. There is of course the problem of the two laughters: those who understand Italian will laugh immediately, those who don’t will have to wait for [the] Swedish translation. And then there are those of you who won’t know whether to laugh the first time or the second. Dario Fo, Nobel Lecture (Fo 130) Writers create national literature with their language, but world literature is written by translators. José Saramago (Appel 40) Introduction Translation is quite often a precondition for the Nobel Prize in Literature, to the extent that the canonization of a world-class writer can entail in part the canonization of his or her extant translations. One critic inscribes Mo Yan’s 2012 win in a network of “collaborators,” a process true of most writers working outside global literary languages: “[H]is prize winning is a success of collaboration with the author as the nodal point amid a necessary global network of cosmopolitanites, including translators, publishers, nominators, readers, [and] the media...” (Wang 178).