Wb Yeats and 20Th Century Russian Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folia Orient. Bibliotheca I.Indd

FOLIA ORIENTALIA — BIBLIOTHECA VOL. I — 2018 DOI 10.24425/for.2019.126132 Yousef Sh’hadeh Jagiellonian University [email protected] The Koran in the Poetry of Alexander Pushkin and Ivan Bunin: Inspiration, Citation and Intertextuality Abstract The Koran became an inspiration to the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837), made obvious in many of his works, such as Imitations of the Koran, The Prophet, and In a Secret Cave. Pushkin studied the translation of the Koran carefully and used many verses of its Surahs in his texts. Many of his contemporary poets and followers were influenced by his poetry, like Ivan Bunin (1870–1953), who continued the traditions of Pushkin. Bunin repeated many thoughts from Koranic discourse and placed them in his poems that were full of faith and spirituality. He wrote many of them at the beginning of the 20th century1, before his emigration to France in 1918, for example: Mohammed in Exile, Guiding Signs and For Treason. It has been noted that Bunin was quoting verses from the Koran to create an intertextual relationships between some Surahs and his poems, showing a great enthusiasm to mystical dimension of Islam. We find this aspect in many works, such as The Night of al-Qadr, Tamjid, Black Stone of the Kaaba, Kawthar, The Day of Reckoning and Secret. It can also be said that a spiritual inspiration and rhetoric of Koran were not only attractive to Pushkin and Bunin, but also to a large group of Russian poets and writers, including Gavrila Derzhavin, Mikhail Lermontov, Fyodor Tyutchev, Yakov Polonsky, Lukyan Yakubovich, Konstantin Balmont, and others. -

SUMMARY Articles and Reports History of Literature Natalia L

SUMMARY Articles and Reports History of Literature Natalia L. Lavrova. The motif of Divine Narcissism in Baroque Literature. This article focuses on historical fate of the motif of divine narcissism which is explicitly actualized in Baroque literature. Key words: Narcissus myth; Baroque; divine narcissism; «Divine Comedy»; Ficino; «Paradise Lost». Olga A. Bogdanova. «Country-estate Culture» in the Russian Literature of the XIX – beg. XX Century. Social and Cultural Aspects. The country estate of the XIX century as a phenomenon of Russian culture united the parts of the Russian nation – nobility and peasantry, split in the process of Peter’s reforms – into a certain wholeness. Both Europeism and «soilness» of the Russian classical literature came from the fact that its creators, the Russian landlords with their European education, within the estate were closely tied with the peasants and thus could express the folk mentality by the European artistic language. The town intellectuals of the «Silver Age», alien to the «country-estate culture», on the opposite, lost the immediate link with the common people and created the literature, which was far from the national religious tradition («legend»), not that of «soil», but of «catastrophy». Key words Country-estate; estate nobility; peasantry; Russian classical literature; «legend»; intellectuals; Silver Age; «soillessness»; catastrophism. Yulia N. Starodubtseva. Afanasy Fet’s Works as Perceived by Aleksandr Blok (using Aleksandr Blok’s library as a study case). The author aims to investigate the influence of Afanasy Fet’s work on Aleksandr Blok by analyzing the notes made by Blok when reading. This method makes it possible to address the issue on the basis of factual and therefore more reliable material, and pairing poems for comparison is facilitated by the fact that Fet’s side is preselected by Blok’s notes. -

Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes in the Context of Symbolism Andrey Konovalov1,A Liudmila Mikheeva2,* Yulia Gushchina3,B

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 572 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2021) Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes in the Context of Symbolism Andrey Konovalov1,a Liudmila Mikheeva2,* Yulia Gushchina3,b 1 Institute of Fine Arts, Moscow Pedagogical State University, Moscow, Russia 2 Department of General Humanitarian Disciplines, Russian State Specialized Academy of Arts, Moscow, Russia 3 Likhachev Russian Research Institute for Cultural and Natural Heritage, Moscow, Russia a Email: [email protected] b Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The present article focuses on the artistic culture of the Silver Age and the remarkable creative atmosphere of Russia at the turn of the 20th century characterized by the synthesis of arts: drama, opera, ballet, and scenography. A key figure of the period was Sergei Diaghilev, the editor and publisher of the magazines Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) and The Yearbook of the Imperial Theatres, the founder of the famous Ballets Russes in Paris, the organizer of exhibitions of Russian artists of different schools and movements. The article studies the features of Symbolism as an artistic movement and philosophy of art of the Silver Age, a spiritual quest of artistic people of the time, and related and divergent interests of representatives of different schools and trends. The Silver Age is considered the most sophisticated and creative period of Russian culture, the time of efflorescence, human spirit, creativity, the rise of social forces, general renewal, in other words, Russian spiritual and cultural renaissance. -

Translation of Selected Poems by K. Balmont

Swarthmore College Works Russian Faculty Works Russian 2015 Translation Of Selected Poems By K. Balmont K. Balmont Sibelan E.S. Forrester Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian Part of the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation K. Balmont and Sibelan E.S. Forrester. (2015). "Translation Of Selected Poems By K. Balmont". Russian Silver Age Poetry. 33-37. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian/220 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Konstantin Balmont 33 became more demanding; his poetry was described as a magnificent transla- tion from an unknown original, though always praised for its musicality. He himself translated poetry from numerous languages; authors he rendered from English included Blake, Poe, Shelley, Whitman, and Wilde. Balmont emigrated to France in 1922 and lived there in poverty, as did most émigré poets; he suffered a gradual mental decline that limited his ability to write and died in 1942. Verblessness [Безглагольность] In the nature of Russia there’s some weary tenderness, The unspeaking pain of a deep-buried sorrow, Ineluctable grief, voicelessness, endlessness, A high frozen sky, and horizons unfolding. Come out here at dawn to the slope of the hillside— A chill smoking over the shivering river, The massive pine forest stands darkly, unmoving, And the heart feels such pain, and the heart is not gladdened. -

London International Antiquarian Book Fair June 1-3, 2017 the Olympia National Hall 2017

Stand F14 LONDON INTERNATIONAL ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR June 1-3, 2017 The Olympia National Hall 2017 LONDON LONDON INTERNATIONAL ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR The Olympia National Hall 2017 Visit us at Stand F14 June 1-3, 2017 The Olympia National Hall Hammersmith Road, London W14 8UX LONDON Thursday 1st June: 1pm–8pm Friday 2nd June: 11am–7pm Saturday 3rd June: 11am–4pm Images and more information available on request. The prices are in £. Shipping costs are no included. We accept wire transfer and PayPal. Cover and pages design with details from our books in this list. Dickens in woodcuts 1. Dickens Charles Sverchok na pechi [The Cricket on the Hearth]. [Translation by M. Shishmareva]. Cover and illustrations by A. Kravchenko Moskva-Leningrad, Gosudarstvennoe izdatelʹstvo, 1925. 16mo, 143, [1] pp., ill. In publisher’s illustrated wrappers Near very good condition Limited to 4 000 copies. Fine illustrated edition of The Cricket on the Hearth (1845) in Russian. For the first time this translation appeared in Dickens’s Collected works (St. Petersburg, vol. 7, 1894). Our edition doesn’t contain the translator’s name. Cover, headpieces, endpieces and five full-page woodcuts by graphic artist Aleksey Kravchenko (1889–1940). He is considered a master of woodcut. He studied at Simon Hollosy’s art school in Munich and at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture under Konstantin Korovin and Valentin Serov. He was a member of the Four Arts Society of Artists. For the first time Russian artists illustrated Dickens’ works in the end of the XIX century. In the 20s of the XX century new generation of the Russian graphic artists, avant-garde minds, came back to Dickens and prepared illustrated editions of Great ex- pectations (Mitrokhin and Budogoskii, 1929 and 1935), Hard times (Favorsky, 1933), The posthumous papers of the Pickwick club (Milashevsky 1933). -

Construction and Tradition: the Making of 'First Wave' Russian

Construction and Tradition: The Making of ‘First Wave’ Russian Émigré Identity A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of History from The College of William and Mary by Mary Catherine French Accepted for ____Highest Honors_______________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Frederick C. Corney, Director ________________________________________ Tuska E. Benes ________________________________________ Alexander Prokhorov Williamsburg, VA May 3, 2007 ii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Part One: Looking Outward 13 Part Two: Looking Inward 46 Conclusion 66 Bibliography 69 iii Preface There are many people to acknowledge for their support over the course of this process. First, I would like to thank all members of my examining committee. First, my endless gratitude to Fred Corney for his encouragement, sharp editing, and perceptive questions. Sasha Prokhorov and Tuska Benes were generous enough to serve as additional readers and to share their time and comments. I also thank Laurie Koloski for her suggestions on Romantic Messianism, and her lessons over the years on writing and thinking historically. Tony Anemone provided helpful editorial comments in the very early stages of the project. Finally, I come to those people who sustained me through the emotionally and intellectually draining aspects of this project. My parents have been unstinting in their encouragement and love. I cannot express here how much I owe Erin Alpert— I could not ask for a better sounding board, or a better friend. And to Dan Burke, for his love and his support of my love for history. 1 Introduction: Setting the Stage for Exile The history of communities in exile and their efforts to maintain national identity without belonging to a recognized nation-state is a recurring theme not only in general histories of Europe, but also a significant trend in Russian history. -

Translation, Littérisation, and the Nobel Prize for Literature

TranscUlturAl, vol. 8.1 (2016), 57-75. http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/TC Translation, Littérisation, and the Nobel Prize for Literature Kelly Washbourne Kent State University, USA As I proceed, I will from time to time indicate to you where we are in the manuscript. That way you won’t lose the thread. This will be of help especially to those of you who don’t understand either Italian or Swedish. English speakers will have a tremendous advantage over the rest because they will imagine things I’ve neither said nor thought. There is of course the problem of the two laughters: those who understand Italian will laugh immediately, those who don’t will have to wait for [the] Swedish translation. And then there are those of you who won’t know whether to laugh the first time or the second. Dario Fo, Nobel Lecture (Fo 130) Writers create national literature with their language, but world literature is written by translators. José Saramago (Appel 40) Introduction Translation is quite often a precondition for the Nobel Prize in Literature, to the extent that the canonization of a world-class writer can entail in part the canonization of his or her extant translations. One critic inscribes Mo Yan’s 2012 win in a network of “collaborators,” a process true of most writers working outside global literary languages: “[H]is prize winning is a success of collaboration with the author as the nodal point amid a necessary global network of cosmopolitanites, including translators, publishers, nominators, readers, [and] the media...” (Wang 178). -

Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 11-2013 Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Slavic Languages and Societies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry" (2013). Zea E-Books. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/21 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry N Marcelline Hutton Many Russian women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries tried to find happy marriages, authentic religious life, liberal education, and ful- filling work as artists, doctors, teachers, and political activists. Some very remarkable ones found these things in varying degrees, while oth- ers sought unsuccessfully but no less desperately to transcend the genera- tions-old restrictions imposed by church, state, village, class, and gender. Like a Slavic “Downton Abbey,” this book tells the stories, not just of their outward lives, but of their hearts and minds, their voices and dreams, their amazing accomplishments against overwhelming odds, and their roles as feminists and avant-gardists in shaping modern Russia and, in- deed, the twentieth century in the West. -

Russian Silver Age Poetry: Texts and Contexts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Works Swarthmore College Works Russian Faculty Works Russian 2015 Russian Silver Age Poetry: Texts And Contexts Sibelan E. S. Forrester Swarthmore College, [email protected] M. Kelly Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian Part of the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Sibelan E. S. Forrester and M. Kelly. (2015). "Russian Silver Age Poetry: Texts And Contexts". Russian Silver Age Poetry: Texts And Contexts. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian/160 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTRODUCTION: POETRY OF THE RUSSIAN SILVER AGE Sibelan Forrester and Martha Kelly oetry is only one of the exciting cultural achievements of the Russian Pfin-de-siècle, which has come to be known as the Silver Age. Along with the Ballets russes, the music of Alexander Scriabin or Igor Stravinsky, the avant- garde painting of Kazimir Malevich or Marc Chagall, and the philosophical writings of Lev Shestov or Nikolai Berdyaev, poetry is one of the era’s most precious treasures. The Silver Age witnessed an unprecedented and fruitful interaction between Russian literature and the other arts, sometimes within the same person: several of the major poets were (or could have been) musi- cians and composers; others were painters, important literary critics, religious thinkers, scholars, or philosophers. -

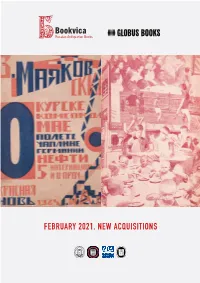

February 2021. New Acquisitions F O R E W O R D

FEBRUARY 2021. NEW ACQUISITIONS F O R E W O R D Dear friends & colleagues, We are happy to present our first catalogue of the year in which we continue to study Russian and Soviet reality through books, magazines and other printed materials. Here is a list of contents for your easier navigation: ● Architecture, p. 4 ● Women Studies, p. 19 ● Health Care, p. 25 ● Music, p. 34 ● Theatre, p. 40 ● Mayakovsky, p. 49 ● Ukraine, p. 56 ● Poetry, p. 62 ● Arctic & Antarctic, p. 66 ● Children, p. 73 ● Miscellaneous, p. 77 We will be virtually exhibiting at Firsts Canada, February 5-7 (www.firstscanada.com), andCalifornia Virtual Book Fair, March 4-6 (www.cabookfair.com). Please join us and other booksellers from all over the world! Stay well and safe, Bookvica team February 2021 BOOKVICA 2 Bookvica 15 Uznadze St. 25 Sadovnicheskaya St. 0102 Tbilisi Moscow, RUSSIA GEORGIA +7 (916) 850-6497 +7 (985) 218-6937 [email protected] www.bookvica.com Globus Books 332 Balboa St. San Francisco, CA 94118 USA +1 (415) 668-4723 [email protected] www.globusbooks.com BOOKVICA 3 I ARCHITECTURE 01 [HOUSES FOR THE PROLETARIAT] Barkhin, G. Sovremennye rabochie zhilishcha : Materialy dlia proektirovaniia i planovykh predpolozhenii po stroitel’stvu zhilishch dlia rabochikh [i.e. Contemporary Workers’ Dwellings: Materials for Projecting and Planned Suggestions for Building Dwellers for Workers]. Moscow: Voprosy truda, 1925. 80 pp., 1 folding table. 23x15,5 cm. In original constructivist wrappers with monograph MB. Restored, pale stamps of pre-war Worldcat shows no Ukrainian construction organization on the title page, pp. 13, 45, 55, 69, copies in the USA. -

1 Russ 689 Thurs 2:30 – 4:20 Hgs 217 Мы Для Новой Красоты Нарушаем Все Законы Прест

RUSS 689 RUSSIAN SYMBOLIST POETRY GRADUATE SEMINAR FALL 2013 THURS 2:30 – 4:20 HGS 217B MARIJETA BOZOVIC Мы для новой красоты Нарушаем все законы Преступаем все черты. — Дмитрий Мережковский DESCRIPTION: This graduate seminar explores Russian Symbolist poetry in cultural and international contexts. We will study the philosophical foundations (Nietzsche, Solovyov); the preoccupation with various temporalities (modernity); the longing for total art (Wagner) bounded by lyric form; aestheticism; utopianism; decadence; and other topics. Our readings include the works of Vladimir Solovyov, Valery Briusov, Konstantin Balmont, Fedor Sologub, Zinnaida Gippius, Mikhail Kuzmin, Viacheslav Ivanov, Andrei Bely, and Aleksandr Blok—as well as of “post-Symbolists” Nikolai Gumilyov, Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, and Marina Tsvetaeva. Our approach emphasizes prosody, genre, and medium as well as the dissemination of ideas across media and cultures; our weekly practices will involve close reading, research, theoretical reframing, and ongoing collaborative participation and presentations. REQUIREMENTS: Seminar requirements include challenging reading assignments and excellent preparation for each discussion. You will be asked to post a close reading, response, or intervention (approximately 4–6 paragraphs; other media also welcome) based on the readings prior to each session; we will experiment with social media platforms as part of our ongoing collaborative attempt to enhance and extend discussion—and to think about medium and technology even as we try to find creative ways to misuse the latter. Other assignments include short presentations on meter and translations; a topic proposal for the final course assignment; and a final paper written in conference presentation form. We will deliver these papers in an informal setting at the end of the semester: the goal is for each student to leave the course with a ready original, beautifully written, and practiced conference paper on Russian poetry. -

“Barbaric Yawp” in Russian

Rocznik Komparatystyczny — Comparative Yearbook 4 (2013) Andrey Azov Moskóvskiy Gosudárstvennyy Universitét “Barbaric Yawp” in Russian Whitman’s poetry was translated into Russian by a number of transla- tors, most notably by Kornei Chukovsky, who began writing on Whitman and translating his poetry in the first decade of the 20th century. His first transla- tions of Whitman appeared alongside the translations by Konstantin Balmont, a prominent figure of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry, and incited a rather heated polemic on whose renditions were better. In 1920 Balmont emigrated from the Soviet Russia, while Chukovsky stayed, and was gradually elevated in the literary ranks, steadily becoming one of the leading authorities on transla- tion.1 In 1936 he published the first complete translation of “Song of Myself.” As far as I could ascertain, there have been no other published translations of this poem into Russian. This may be explained both by the enormity of the task and, quite possibly, by the general reverence for Chukovsky’s translations.2 As for the yawp in “Song of Myself,” the final Chukovsky’s rendition is rather puzzling. Here is what he does (Whitman, 1982: 100): 1 He is celebrated, for instance, for his book on literary translation Высокое искусство (A High Art), which was immensely popular in Russia. It was translated into English by Lauren Leighton under the title The Art of Translation: Kornei Chukovsky’s A High Art. 2 Vladimir Britanishsky, in the foreword to a collection of his translations of American poetry, recalls that when in 1982 (over a decade after Chukovsky’s death) a definitive Rus- sian edition of Leaves of Grass was being prepared, he was asked to re-translate several of Whitman’s poems previously translated by Chukovsky.