Livret Philadelphia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet(5 December 1820 - 3 December 1892) Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet, later changed his name to Shenshin was a Russian poet regarded as one of the finest lyricists in Russian literature. <b>Biography</b> <b>Origins</b> The circumstances of Afanasy Fet's birth have been the subject of controversy, and some uncertainties still remain. Even the exact date is unknown and has been cited as either October 29 (old style), or November 23 or 29, 1820. Brief biographies usually maintain that Fet was the son of the Russian landlord Shenshin and a German woman named Charlotta Becker, an that at the age of 14 he had to change his surname from his father's to that of Fet, because the marriage of Shenshin and Becker, registered in Germany, was deemed legally void in Russia. Detailed studies reveal a complicated and controversial story. It began in September 1820 when a respectable 44-year old landlord from Mtsensk, Afanasy Neofitovich Shenshin, (described as a follower of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's ideas) returned to his Novosyolky estate from the German spa resorts where he had spent a year on a recreational trip. There he had rented rooms in the house of Karl Becker and fell for his daughter Charlotta Elizabeth, a married woman with a one-year-old daughter named Carolina, and pregnant with another child. As to what happened next, opinions vary. According to some sources. Charlotta hastily divorced her husband Johann Foeth, a Darmstadt court official, others maintain that Shenshin approached Karl Becker with the idea that the latter should help his daughter divorce Johann, and when the old man refused to cooperate, kidnapped his beloved (with her total consent). -

Folia Orient. Bibliotheca I.Indd

FOLIA ORIENTALIA — BIBLIOTHECA VOL. I — 2018 DOI 10.24425/for.2019.126132 Yousef Sh’hadeh Jagiellonian University [email protected] The Koran in the Poetry of Alexander Pushkin and Ivan Bunin: Inspiration, Citation and Intertextuality Abstract The Koran became an inspiration to the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837), made obvious in many of his works, such as Imitations of the Koran, The Prophet, and In a Secret Cave. Pushkin studied the translation of the Koran carefully and used many verses of its Surahs in his texts. Many of his contemporary poets and followers were influenced by his poetry, like Ivan Bunin (1870–1953), who continued the traditions of Pushkin. Bunin repeated many thoughts from Koranic discourse and placed them in his poems that were full of faith and spirituality. He wrote many of them at the beginning of the 20th century1, before his emigration to France in 1918, for example: Mohammed in Exile, Guiding Signs and For Treason. It has been noted that Bunin was quoting verses from the Koran to create an intertextual relationships between some Surahs and his poems, showing a great enthusiasm to mystical dimension of Islam. We find this aspect in many works, such as The Night of al-Qadr, Tamjid, Black Stone of the Kaaba, Kawthar, The Day of Reckoning and Secret. It can also be said that a spiritual inspiration and rhetoric of Koran were not only attractive to Pushkin and Bunin, but also to a large group of Russian poets and writers, including Gavrila Derzhavin, Mikhail Lermontov, Fyodor Tyutchev, Yakov Polonsky, Lukyan Yakubovich, Konstantin Balmont, and others. -

Golden Age of Russian Literature New York - Washington 03-15 October 2015

Golden Age of Russian Literature New York - Washington 03-15 October 2015 ARTISTTV EXPO EXHIBITION in USA 3 2 Representatives of the Shaliapin music school with school director Irina Strykava Opera singer Irina Velichko Tenor Aleksaandr Lesin Memorable photo for memory participants of the concert «Cover girl» Superior room in the main building of the Russian Foreign Ministry on Smolenksoy Square opened its doors to the exhibition «Golden Age» of Russian literature» in Moscow from 16-24 september 2015 At the opening were well-known artists Irina Velichko and Alexander Lesin that sangs opera Speech by the deputy Department for songs. Culture of the Russian Foreign Ministry Ivanov Aleksey Vladimirovich Teachers and the best students of the director and organizer ARTISTTV Shalapin music school Moscow played and Yurchenko Andrey Anatolyevich sang for visitors. Curator Julia Jurchenko and Olga Mironovna Zinovieva - the wife of Alexander painter Svetlana Malahova Zinoviev, companion, guardian of the creative and intellectual heritage of Alexander Alexandrovich Zinoviev, the world-famous Russian thinker, On cover philosopher, logic, sociologist, writer and citizen. picture Andrei Podgorny «Sprout» Dear friends ! This booklet is catalogue , but has been designed to study. It get not For over a year, the project «Golden Age» of Russian literature» only the contemporary art culture of Russia, but also to learn the walking on the world. We make exhibition in different countries cultural origins of the Russian culture of the 19th century. and cities, and everywhere we were met with great success. Poems, sayings , citation of great writers - are selected in such a Of course this is due to the large interest in the theme of way that the reader knew what most deeply influence to Russian exhibition. -

Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial Board T

GUIDE Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial board T. Liptuga, G. Zakipnaya, G. Semykina, A. Yavorskaya Authors A. Yavorskaya, G. Semykina, Y. Karakina, G. Zakipnaya, L. Melnichenko, A. Bozhko, L. Liputa, M. Kotelnikova, I. Savrasova English translation O. Voronina Photo Georgiy Isayev, Leonid Sidorsky, Andrei Rafael О417 Одеський літературний музей : Путівник / О. Яворська та ін. Ред. кол. : Т. Ліптуга та ін., – Фото Г. Ісаєва та ін. – Одеса, 2017. – 160 с.: іл. ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 Odessa Literary Museum: Guide / A.Yavorskaya and others. Editorial: T. Liptuga and others, - Photo by G.Isayev and others. – Odessa, 2017. — 160 p.: Illustrated Guide to the Odessa Literary Museum is a journey of more than two centuries, from the first years of the city’s existence to our days. You will be guided by the writers who were born or lived in Odessa for a while. They created a literary legend about an amazing and unique city that came to life in the exposition of the Odessa Literary Museum UDC 069:801 (477.74) Англійською мовою ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 © OLM, 2017 INTRODUCTION The creators of the museum considered it their goal The open-air exposition "The Garden of Sculptures" to fill the cultural lacuna artificially created by the ideo- with the adjoining "Odessa Courtyard" was a successful logical policy of the Soviet era. Despite the thirty years continuation of the main exposition of the Odessa Literary since the opening day, the exposition as a whole is quite Museum. The idea and its further implementation belongs he foundation of the Odessa Literary Museum was museum of books and local book printing and the history modern. -

MAXIM LANDO, Piano

Candlelight Concert Society Presents MAXIM LANDO, piano Saturday, September 26, 2020, 7:30pm Broadcast Virtually PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893) The Seasons, op. 37a January: At the Fireside February: Carnival March: Song of the Lark April: Snowdrop May: Starlit Nights June: Barcarolle July: Song of the Reaper August: Harvest September: The Hunt October: Autumn Song November Troika December: Christmas NIKOLAI KAPUSTIN (1937-2020) Eight Concert Études, op 40 Prelude Reverie Toccatina Remembrance Raillery Pastorale Intermezzo Finale wine stewards. As a result, the singing and dancing that Program Notes takes place at their parties is always vigorous. Tchaikovsky captures this vitality through rapidly ______________________________ moving chords and arpeggios along with sudden Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) changes from loud to soft. THE SEASONS, OP. 37a March: Chant de l'alouette (Song of In 1875, the editor of the Saint Petersburg music the Lark) magazine Nouvellist, Nikolay Matveyevich The field shimmering with flowers, Bernard, commissioned Tchaikovsky to write twelve the stars swirling in the heavens, short piano pieces, one for each month of the year. The the song of the lark commission came just as Tchaikovsky was enjoying fills the blue abyss. the resounding success of the Boston premiere of his (Apollon Maykov) First Piano Concerto (while simultaneously resenting its lukewarm reception in St. Petersburg). Bernard’s The melody Tchaikovsky creates for this piece imitates plan was to publish the pieces in each of the monthly not only the trilling of the lark through its ornamentation editions of the magazine throughout 1876. Bernard but also the swooping of the bird in flight through its chose the subtitles and epigraphs for the pieces with recurring six-note motif, which alternately rises and an eye to the experiences and emotions that were falls. -

Key of F Minor, German Designation)

F dur C F Dur C EFF DOOR C (key of F major, German designation) F moll C f Moll C EFF MAWL C (key of f minor, German designation) Fa bemol majeur C fa bémol majeur C fah bay-mawl mah-zhör C (key of F flat major, French designation) Fa bemol mayor C FAH bay-MAWL mah-YAWR C (key of F flat major, Spanish designation) Fa bemol menor C FAH bay-MAWL may-NAWR C (key of f flat minor, Spanish designation) Fa bemol mineur C fa bémol mineur C fah bay-mawl mee-nör C (key of f flat minor, French designation) Fa bemolle maggiore C fa bemolle maggiore C FAH bay-MOHL-lay mahd-JO-ray C (key of F flat major, Italian designation) Fa bemolle minore C fa bemolle minore C FAH bay-MOHL-lay mee-NO-ray C (key of f flat minor, Italian designation) Fa diese majeur C fa dièse majeur C fah deeezz mah-zhör C (key of F sharp major, French designation) Fa diese mineur C fa dièse mineur C fah deeezz mee-nör C (key of f sharp minor, French designation) Fa diesis maggiore C fa diesis maggiore C FAH deeAY-zeess mahd-JO-ray C (key of F sharp major, Italian designation) Fa diesis minore C fa diesis minore C FAH deeAY-zeess mee-NO-ray C (key of f sharp minor, Italian designation) Fa maggiore C fa maggiore C FAH mahd-JO-ray C (key of F major, Italian designation) Fa majeur C fa majeur C fah mah-zhör C (key of F major, French designation) Fa mayor C FAH mah-YAWR C (key of F major, Spanish designation) Fa menor C FAH may-NAWR C (key of f minor, Spanish designation) Fa mineur C fa mineur C fah mee-nör C (key of f minor, French designation) Fa minore C fa minore C FAH mee-NO-ray -

Concert Program

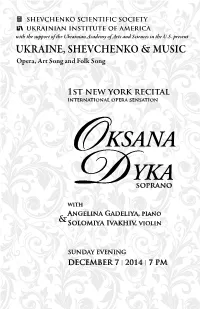

Oksana Dyka, soprano Angelina Gadeliya, piano • Solomiya Ivakhiv, violin I. Bellini Vincenzo Bellini Casta Diva (1801-1835) from Norma (1831) Program Mozart Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro (1756-1791) from The Marriage of Figaro (1786) Rossini Gioachino Rossini Selva opaca, Recitative and Aria (1792-1868) from Guglielmo Tell (William Tell, 1829) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya II. Shchetynsky Alexander Shchetynsky An Episode in the Life of the Poet, (b. 1960) an afterword to the opera Interrupted Letter (2014) World Premiere Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya III. From Poetry to Art Songs 1: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Shtoharenko Andriy Shtoharenko Yakby meni cherevyky (1902-1992) (If I had a pair of shoes, 1939) Silvestrov Valentin Silvestrov Proshchai svite (b. 1937) (Farewell world, from Quiet Songs, 1976) Shamo Ihor Shamo Zakuvala zozulen’ka (1925-1982) (A cuckoo in a verdant grove, 1958) Skoryk Myroslav Skoryk Zatsvila v dolyni (b. 1938) (A guelder-rose burst into bloom, 1962) Mussorgsky Modest Mussorgsky Hopak (1839-1881) from the opera Sorochynsky Fair (1880) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya 2 Program — INTERMISSION — I V. Beethoven Ludwig van Beethoven Allegro vivace (1770-1827) from Sonata in G Major, Op. 30 (1801-1802) Vieuxtemps Henri Vieuxtemps Désespoir (1820-1881) from Romances sans paroles, Op. 7, No. 2 (c.1845) Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya V. From Poetry to Art Songs 2: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Lysenko Mykola Lysenko Oy, odna ya odna (1842-1912) (I’m alone, so alone, 1882) Rachmaninov Sergei Rachmaninov Poliubila ya na pechal’ svoyu, (1873-1943) Op. 8, No. 4 (I have given my love, 1893) Stetsenko Kyrylo Stetsenko Plavai, plavai, lebedon’ko (1882-1922) (Swim on, swim on, dear swan, 1903) Dankevych Konstantyn Dankevych Halia’s Aria (1905-1984) from the opera Nazar Stodolia (1960) VI. -

47Th SEASON PROGRAM NOTES Week 2 July 21–27, 2019

th SEASON PROGRAM NOTES 47 Week 2 July 21–27, 2019 Sunday, July 21, 6 p.m. The marking for the first movement is of study at the University of California, San Monday, July 22, 6 p.m. unusual: Allegramente is an indication Diego, in the mid-1980s that brought a new more of character than of speed. (It means and important addition to his compositional ZOLTÁN KODÁLY (1882–1967) “brightly, gaily.”) The movement opens palette: computers. Serenade for Two Violins & Viola, Op. 12 immediately with the first theme—a sizzling While studying with Roger Reynolds, Vinko (1919–20) duet for the violins—followed by a second Globokar, and Joji Yuasa, Wallin became subject in the viola that appears to be the interested in mathematical and scientific This Serenade is for the extremely unusual song of the suitor. These two ideas are perspectives. He also gained further exposure combination of two violins and a viola, and then treated in fairly strict sonata form. to the works of Xenakis, Stockhausen, and Kodály may well have had in mind Dvorˇ ák’s The second movement offers a series of Berio. The first product of this new creative Terzetto, Op. 74—the one established work dialogues between the lovers. The viola mix was his Timpani Concerto, composed for these forces. Kodály appears to have been opens with the plaintive song of the man, between 1986 and 1988. attracted to this combination: in addition and this theme is reminiscent of Bartók’s Wallin wrote Stonewave in 1990, on to the Serenade, he wrote a trio in E-flat parlando style, which mimics the patterns commission from the Flanders Festival, major for two violins and viola when he was of spoken language. -

Here Where the Forest Thins, a Kite…’ 24 ‘Why, O Willow, to the River…’ 25 ‘In the Air’S Oppressive Silence…’ 26 ‘Pale Showed the East… Our Craft Sped Gently…’ 27

FYODOR TYUTCHEV Selected Poems Fyodor Tyutchev Selected Poems Translated with an Introduction and Notes by John Dewey BRIMSTONE PRESS First published in 2014 Translations, Introduction and Notes copyright © John Dewey ISBN 978-1-906385-43-9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by Brimstone Press The Mount, Buckhorn Weston Gillingham, Dorset, SP8 5HT www.brimstonepress.co.uk Printed and bound in Great Britain by imprintdigital.com Contents Introduction xi First Love: Amélie ‘That day remains in memory…’ 2 ‘A golden time still haunts my senses…’ 3 To N. 4 To N.N. 5 Two Sisters: Eleonore, Clotilde To Two Sisters 8 ‘To sort a pile of letters, on…’ 9 ‘Still love torments me with a vengeance…’ 10 K.B. 11 Nature Summer Evening 14 Thunderstorm in Spring 15 Evening 16 Spring Waters 17 Sea Stallion 18 ‘Knee-deep in sand our horses flounder…’ 19 Autumn Evening 20 Leaves 21 ‘What a wild place this mountain gorge is!..’ 23 ‘Here where the forest thins, a kite…’ 24 ‘Why, O willow, to the river…’ 25 ‘In the air’s oppressive silence…’ 26 ‘Pale showed the east… Our craft sped gently…’ 27 Philosophical Reflections Silentium! 30 Mal’aria 31 The Fountain 32 ‘My soul, Elysium of silent shades…’ 33 ‘Nature is not what you would have it…’ 34 ‘Nous avons pu tous deux, fatigués du voyage…’ 36 Columbus 37 Two Voices 38 ‘See on the trackless river, riding…’ 39 Day and Night ‘Just as the ocean’s mantling -

Michael Wachtel Curriculum Vitae

Michael Wachtel Curriculum Vitae ADDRESS: Home: 294 Western Way, Princeton, NJ, 08540 Tel: (609) 497-3288 Office: Slavic Department, 225 East Pyne, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 Tel: (609) 258-0114 Fax: (609) 258-2204 E-mail: [email protected] EMPLOYMENT: 1990–96: Assistant Professor, Slavic Department, Princeton University 1996–present: Full Professor, Slavic Department, Princeton University EDUCATION: Harvard University Ph.D. Comparative Literature, degree received November, 1990 M.A. Comparative Literature, degree received March, 1986 Moscow State University, USSR 9/88-6/89 Universität Konstanz, West Germany 10/87-7/88, 10/82-9/83 Pushkin Institute, Moscow, USSR 9/84-12/84 Yale University 9/78-6/82 B.A. Comparative Literature, summa cum laude, departmental distinction, degree received June, 1982. HONORS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2010 Likhachev Foundation fellowship (two weeks in St. Petersburg) 2007–2008 NEH grant Guggenheim Fellowship 1 2002 Awarded AATSEEL prize for best new translation (for Vyacheslav Ivanov, Selected Essays): NB: I was editor of translation, not translator. 1999 Awarded AATSEEL prize for best new book in Literary/Cultural Studies (for The Development of Russian Verse) 9/94-9/97 Princeton University Gauss Preceptorship 7/93-8/93 Princeton University grant (Committee for Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences) for research in Germany, Italy, and Russia 6/91-7/91 Princeton University grant (Committee for Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences) for research in Italy and Russia 9/88-6/89 International Research and Exchanges (IREX) fellowship (and Fulbright-Hays Travel Grant) for dissertation research in the USSR 9/87-6/88 Fulbright fellowship (study and research in Konstanz, Germany) 9/86-6/87 Harvard Merit fellowship and U.S. -

Download File

Intimations of the Absolute: Afanasii Fet‘s Metalinguistic and Aspectual Poetics John Wright Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 John Wright All rights reserved ABSTRACT Intimations of the Absolute: Afanasii Fet‘s Metalinguistic and Aspectual Poetics John Wright This work explores the poetry of Afanasii Fet from the perspective that careful observation of certain meta-lingual features of his work, most notably his use of verbal aspect, are relevant to understanding his metaphysical strivings and philosophical beliefs. The analytical focus is on a series of representative lyrics from throughout Fet‘s career. Each individual analysis is then interpreted in the light of Fet‘s biography, his poetic dialogue with his predecessors, and his unhappy romance with Maria Lazic. The analysis of the poetry considers that Fet‘s poetic language often uses the aspectual forms of the Russian verb as a significant organizing principle. Aspect as such in these lyrics interacts with the paraphrasable meaning, while it often stands out in a mathematically or graphically precise form. The introduction reviews Fet‘s life and his autobiographical works and offers a new reading of his autobiography to contextualize the metaphysical tension that plagued the poet throughout his long career. Chapter 1 gives linguistic and philosophical foundations for this approach, while Chapter 2 offers a set of individual readings to demonstrate the variety of types of meaning to which aspectual structures contribute in Fet‘s work. Chapter 3 considers verbal aspect in Fet‘s spring-themed poems, which express some of his most foundational meta-poetic and metaphysical ideas. -

Sl.4: Russian Literature and Culture from the Golden Age to the Silver Age

Sl.4: Russian Literature and Culture from the Golden Age to the Silver Age Chekhov and Tolstoy in Crimea (1901) Course Adviser: Dr Daniel Green ([email protected]) Handbook 2020-21 (updated June 2020) Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………................................................ 3 2. Overview of Texts and Topics for 2020-21…………………………………….. 3 3. Teaching & Assessment………………………………………………………………… 4 4. Preparatory Reading…………………………………………………………………….. 5 5. Reading Lists………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Using the Reading Lists……………………………………………………… 5 Section A: Set Texts…………………………………………………………… 6 Section B: Topics……………………………………………………………….. 10 2 Sl.4: Russian Literature and Culture from the Golden Age to the Silver Age Introduction The nineteenth century saw the rapid development of Russian literary culture – from the emergence of the modern Russian literary language in poetry, to the rise of the great Russian novel, and, by the end of the century, the launch of modernism in Russia. Bold in their formal and aesthetic innovations, the works of this century pose the decisive questions of Russian modernity and pursue urgent issues of social, political and theological import. The course is a study of Russian literature from the beginning of the nineteenth century through to the very early twentieth century and introduces students to a range of authors, genres and issues. In order to achieve a balance of depth and breadth, the paper is organised around the study of two set texts and four topics. (There are suggested pathways through the texts and topics tailored to Part IB, option A (ex-ab initio) students, but students should not feel limited to these.) Overview of Texts and Topics for 2020-21 Set Texts: A1. Aleksandr Pushkin, Evgenii Onegin (1825-32) A2.