Readings Advised by Venerable Robina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REACHING OUT: a History of and Contemporary Look at the Centers, Projects and Services of FPMT

REACHINGOUT REACHING OUT: A history of and contemporary look at the Centers, Projects and Services of FPMT Lama Yeshe supervises building of Kopan FPMT pioneers: Peter Kedge, Lama Yeshe, Gompa extension, 1976 Sister Max1 and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, 1982 We make the ocean and the fish will come. – Lama Thubten Yeshe pi-o-neer: And funding? Lama Yeshe was brutal in his insistence 1. One who ventures into unknown or unclaimed that centers and students be self-sufficient and often territory to settle. encouraged them to start businesses. Lama’s early students 2. One who opens up new areas of thought, research or were made up of those from the anti-establishment genera- development. tion and many had been quite proud to cheat on their taxes, accept welfare payments, shoplift or sell marijuana as ama Thubten Yeshe (1935-1984), founder of the methods to remain on the fringes of society. Lama insisted Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana that his students “do what society people do” and function LTradition (FPMT), was many things to many people. as professional members of the world. Breaking the law or What seems a constant impression from those who knew following the “hippie” notion that money and capitalism him was that Lama Yeshe was big. “Think big,” “big love,” were necessary evils would get them nowhere. It was one’s – these are catch-phrases commonly attributed to Lama. motivation that corrupted ventures in commerce, and since Some students even claim he often appeared to physically his students were engaging in business practice to be of grow far bigger than his 5 ft 6 in (167 cm) frame. -

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts By Ramin Etesami A thesis submitted to the graduate school in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the International Buddhist College, Thailand March, 20 Abstract The Tulku institution is a unique characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism with a central role in this tradition, to the extent that it is present in almost every aspect of Tibet’s culture and tradition. However, despite this central role and the scope and diversity of the socio-religious aspects of the institution, only a few studies have so far been conducted to shed light on it. On the other hand, an aura of sacredness; distorted pictures projected by the media and film industries;political propaganda and misinformation; and tendencies to follow a pattern of cult behavior; have made the Tulku institution a highly controversial topic for research; and consequently, an objective study of the institution based on a critical approach is difficult. The current research is an attempt to comprehensively examine different dimensions of the Tulku tradition with an emphasis on the issue of its orthodoxy with respect to the core doctrines of Buddhism and the social implications of the practice. In this research, extreme caution has been practiced to firstly, avoid any kind of bias rooted in faith and belief; and secondly, to follow a scientific methodology in reviewing evidence and scriptures related to the research topic. Through a comprehensive study of historical accounts, core Buddhist texts and hagiographic literature, this study has found that while the basic Buddhist doctrines allow the possibility for a Buddhist teacher or an advanced practitioner to “return back to accomplish his tasks, the lack of any historical precedence which can be viewed as a typical example of the practice in early Buddhism makes the issue of its orthodoxy equivocal and relative. -

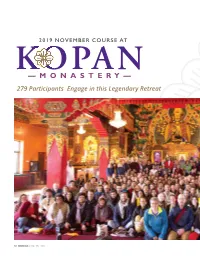

— M O N a S T E R

2019 NOVEMBER COURSE AT KOPAN —MONASTERY— 279 Participants Engage in this Legendary Retreat 52 MANDALA | Issue One 2020 Every year, the November Course, a month-long lamrim meditation course at Kopan Monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal, draws diverse students from around the world. What started in 1971 with a dozen students in attendance, reached a record 279 participants from forty-nine countries this year with Ven. Robina Courtin teaching the course for the first time. This was also the first course held in Kopan’s new Chenrezig gompa. Mandala editor, Carina Rumrill asked Ven. Robina about this year’s course, and we share this beautiful account of her experience and history with this style of retreat. THIS YEAR’S RECORD NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS — 279 PEOPLE FROM FORTY-NINE COUNTRIES — WITH KOPAN’S ABBOT KHEN RINPOCHE THUBTEN CHONYI, VEN. ROBINA COURTIN, AND OTHER TEACHERS AND MEDITATION LEADERS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). Issue One 2020 | MANDALA 53 VEN. ROBINA COURTIN OFFERED A MANDALA TO RINPOCHE REQUESTING TEACHINGS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). AND THE BLESSINGS: YOU COULDN’T HELP BUT FEEL THEM BY VEN. ROBINA COURTIN The Kopan November Course is legendary. The first of what But the beauty of the place was its saving grace: a hill became an annual event, one month of lamrim teachings by surrounded on all sides by the terraced fields of the magnifi cent Lama Zopa Rinpoche to a dozen Westerners fifty years ago, Kathmandu Valley, with mountains to the north and the holy quickly became a magnet for spiritual seekers worldwide. -

Robina S&S Feature Template

Robina_S&S Feature Template 04/10/2013 09:59 Page 1 “If you don’t RESPECT YOURSELF, how can you expect others to?” Our new columnist, the venerable Robina Courtin is an outspoken, tough and fiery Buddhist nun. Each month she answers your questions concerning Buddhism in a modern world. Robina is teaching in London, Somerset, This month it’s how to respect YOU! Scotland, France, Denmark and Sweeden remember my mother would For sure, we do get angry, bad-mouth in November. say this phrase to me, but others, make a mess of our relationships, get See her schedule at I could never hear it. I would jealous, and the rest, and need to be robinacourtin.com. desperately want others to accountable for these parts of ourselves. But Iapprove of, love and respect me, we end up feeling guilty instead, and this is but I couldn’t join the dots between useless: it’s not about taking responsibility at that and my own low self-esteem. In all. It merely reinforces our low self-esteem, The Five Top Regrets of the Dying. She said and we believe it’s permanent, and that it is fact, I didn’t know what it meant! It the top regret was: ‘I wish I’d had the courage who we really are. seemed so true that I wasn’t worthy to live a life true to myself, not the one others expected of me’. or good enough. ON THE BRIGHT SIDE That’s the one! It’s huge, actually, but we This is the irony of the ego, according to the But we also do good things: work hard, have no choice. -

This Is the Published Version: Available from Deakin Research

This is the published version: Halafoff, Anna 2013, Women in Buddhism at the grass roots in Australia, in 2013 : Buddhism at the grassroots : Proceedings of the 2013 Sakyadhita international conference on Buddhist women, Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women, Kailua, Hawaii, pp. 51‐56. Available from Deakin Research Online: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30060001 Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright owner. Copyright : 2013, Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women Edited by: Karma Lekshe Tsomo -tt io' Oopyrl0hl Sakyadhlta 2013 Âll tlghta roserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means now known or lo bs lnvented, electronic or mechanical, including ptotocopying, recording or by any information slorage or retrleval system without written permissions from the respected authors. Buddhism at the Grassroots 13th Sakyadhita lnternational Conference on Buddhist Women Vashali, lndia. Published by: Sakyadhita lnternational Association of Buddhist Women 923 Mokapu Blvd. Kailua, H196734 U.S.A. e-mail : vaishali20l [email protected] www.sakyadhita.org Printed at New Delhi by: Norbu Graphics TABLE OF CONTENTS Buddhist Women of India 1. Examining the Date of Mahapajapatl's Ordination Kustiani I4 2.Rasic Buddhism in Songs: Contemporary Nuns' Oral Traditions in Kinnattr Linda LaMacchia (, 2l 3. Buddhist'Women of the Himalayas Namgey Lhamu 4. Ambedkar's Perspective on Women in Indian Society: Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar 26 Thich Nu Nhu Nguyet Buddhist Women of the World 5. The Changing Roles of Buddhist Nuns and Laywomen in cambodia JJ Thavory Huot 6. Than Hsiang Kindergarten: A Case Study 44 Zhen Yuan Shi 7. -

Recommended by Ven. Robina Courtin

Venerable Robina Recommends Venerable Robina Courtin has been a nun for 29 years in the Gelugpa tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and is a student of the FPMT’s Lama Zopa Rinpoche and Lama Yeshe. She spent 10 years editing for Wisdom Publications followed by over 5 years as the editor of Mandala, the magazine of the FPMT. Ven. Robina currently directs the Liberation Prison Project based in San Francisco serving hundreds of prisoners world-wide, and travels around the world teaching Buddhism at FPMT centers. She has been profiled in the award- winning documentary, Chasing Buddha. For more information visit the LPP website: www.LiberationPrisonProject.org Spiritual Friends Edited by Thubten Dondrub A collection of the favorite guided meditations of senior monks and nuns of the International Mahayana Institute of the FPMT. These meditations center on different Buddhist themes and provide a good resource for the practicing meditator. The book also includes brief spiritual autobiographies that allow the reader to trace each contributor’s entry into and study of Tibetan Buddhism. Destructive Emotions: How Can We Overcome Them? A Scientific Dialogue With the Dalai Lama by His Holiness the Dalai Lama & Daniel Goleman Imagine sitting with the Dalai Lama in his private meeting room with a small group of world-class scientists and philosophers. Although there are no easy answers, the dialogues, which are part of a series sponsored by the Mind and Life Institute, chart an ultimately hopeful course. They are sure to spark discussion among all people who seek peace for themselves and the world. Buddhism for Dummies by Jonathan Landlaw and Stephen Bodian How can the practice of Buddhism enrich our never-ending hectic lives? Discover what it means to be a Buddhist in everyday life and everyday lands in this fascinating Eastern religion. -

The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-Pa Formations

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-09-13 The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations Emory-Moore, Christopher Emory-Moore, C. (2012). The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28396 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/191 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-pa Formations by Christopher Emory-Moore A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2012 © Christopher Emory-Moore 2012 Abstract This thesis explores the adaptation of the Tibetan Buddhist guru/disciple relation by Euro-North American communities and argues that its praxis is that of a self-motivated disciple’s devotion to a perceptibly selfless guru. Chapter one provides a reception genealogy of the Tibetan guru/disciple relation in Western scholarship, followed by historical-anthropological descriptions of its practice reception in both Tibetan and Euro-North American formations. -

MOTHER TARA Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Buddhist Meditation and Healing Centre Rinpoche

HMT is affiliated with the Foundation HOSPICE of for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition founded in 1975 by two Tibetan Lamas, Lama MOTHER TARA Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Buddhist Meditation and Healing Centre Rinpoche. 18 Clifton Street Bunbury WA 6230 t: 9791 9798 w: www.hmt.org.au e: [email protected] July - September 2015 Update From the Nepal Earthquake By Venerable Roger Kunsang, May 2015, Edited by Fran Steele. Firstly, I would like to extend a very big THANK this is the short- and long- YOU to everyone for moving on this emergency term strategy of how we relief effort so quickly by offering to the Nepal can help. Earthquake Support Fund, (http://my.fpmt.org/ donate/socialservicesfund) which we set up Short-Term and Immediate through the FPMT International Office. It has Needs already meant a lot to so many villages. This We have the short-term and has made a HUGE difference. When you are immediate urgent needs freezing cold, have no home, are out in the of the people in mind. This open, in the mountains with hardly any food is food, water, medicine and water left – even for these very hearty and shelter. We are trying people – it is too much. to support the efforts of There are dead people around you: people you the local people to look once knew, some close relatives, your mother, after themselves as the aid etc. Then having to deal with the ground still coming in from overseas shaking from time to time and not knowing if it isn’t reaching them in the will get stronger or just pass. -

The Words of Her Perfect Teacher by Ven

AN EDITOR’S APPROACH TO THE WORDS OF HER PERFECT TEACHER BY VEN. ROBINA COURTIN Over the past several years, Ven. Robina Courtin, a former editor of Mandala, has been compiling and editing the teachings of Lama Zopa Rinpoche into an accessible and clear book on death. Ven. Robina shared with Mandala her process for developing this much-needed publication, which is entitled How to Enjoy Death: Preparing for Life’s Final Challenge without Fear and will be published by Wisdom Publications later this year. Midway through a Kadampa retreat at Institut Vajra Yogini in France, in May 2003, oLama Zopa Rinpoche switched directions and began to teach about how to help our loved ones at the time of death. This was prompted by one of his students telling him, Rinpoche said, that “her father had died suddenly and she didn’t know what to do. That made me think that knowing how to help others at the time of death is such important education to have.” The main source Rinpoche used for the teachings was advice that Choden Rinpoche had given at Land of Medicine Buddha in California a year earlier, as well as a book called Tibetan Ceremonies of the Dead, written by Thupten Sangay and published in Tibetan by the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala. “It was written,” Rinpoche said, o“t educate the Tibetan people outside of their country about their traditions.” By the time the book came to me to be put together – from Ecie Hursthouse in New Zealand, who got it started – Merry Colony and her team in the Education Services department of the FPMT International Office were already nearing completion of Rinpoche’s Heart Advice for Death and Dying and its companion volume, Heart Practices for Death and Dying, published in 2008. -

Lotus Arrow Jun05

LOTUS ARROW Newsletter of the Kurukulla Center for Tibetan Buddhist Studies Number 29, April 200 6 Spiritual Director: Lama Zopa Rinpoche Web: www.kurukulla.org Resident Teacher: Ven. Geshe Tsulga Email: [email protected] 68 Magoun Ave, Medford MA 02155 Phone: (617) 624-0177 From the Director s most of you already know , Venerable Ribur Rinpoche , Awhose Boston visit in 200 0 greatly inspired us to get the house o n Magoun Avenue for the Center, passe d away in India in January, and we all pra y for his swift return. Venerable Ribu r Rinpoche’s advice and support encou r- aged us to purchase the property; an d thanks to his vision we now have a n established center, a significant achiev e- ment that’s helped us move forward fro m our early “altar in a box” days. Keepin g Geshe-la on the radio, talking about the Dharma, on his recent trip to Mexico. See inside for more photos . the center going hasn’t been without it s Buddha’s profound teachings with him. I t the Center, so if you would like to co n- challenges, the most recent of which was , is as rare as seeing stars at noon…not t o tribute your time and skills, let Sean kno w of course, the mortgage drive. be taken for granted. at [email protected]. Billions of thank s The last time I wrote this column fo r And now we can turn our attention t o to all who already volunteer whether occ a- the Lotus Arrow the looming task of rai s- the maintenance and development pr o- sionally or many hours a week. -

Herefore, Prajfiabecomeseven on the Research Are Professionally the Mind May Have Been Made Perceive

PRAJNA: Sharp, Illuminating, and Rationale for the Compassionate Inquisitiveness Establishment of a Network of Contemplative Observatories by KARL BRUNNHOLZL by B. ALAN WALLACE This excerpt is taken from SINCE IHH I URN OF THE CENTURY, Karl Brunnholzl's The Heart a rapidly growing number of sci- Attack Sutra, a practical and entific studies have revealed the clear explanation of The health benefits of various kinds Heart Sutra, perhaps the of mindfulness-based meditation. most well-known of the core Brain scans, EEG measurements, Buddhist texts. behavioral studies, and question- naires have shown the influence of meditation on the brain and As .the basic inquisitiveness behavior, which in the minds of and curiosity of our mind, prajna many people lends some degree is both precise and playful at the ,«****■ of credibility to the practice of same time. Iconographically it is meditation. In the overwhelm- often depicted as a double-blad- ing majority of such studies, ed, flaming sword which is ex- those who conduct and report B. Alan Wallace with Mathieu Ricard tremely sharp. Such a sword ob- (Courtesy of Mind & Life Institute, viously needs to be handled with ...a worldwide network photo by Raphaele Demandre) great care, and mav even seem of contemplative ob- somewhat threatening. servatories linked by tion, and all discoveries pertain- Prajna is indeed threatening to way of the internet, and our ego and to our cherished be- ing to meditation are claimed by ; collaborating with each lief systems since it undermines our very solid-looking objective selves. Prajna means being found- the scientists, who in many cases our verv notion of reality and reality, but it also cuts through out bv ourselves, which first of all other, modeled after the have little or no meditative expe- the reference points upon which the subjective experiencer of such requires taking an honest look at Human Genome Project. -

Commitments, Vows and Recommended Practices for People Who Have Taken Refuge and the Five Lay Vows

COMMITMENTS, VOWS AND RECOMMENDED PRACTICES FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE TAKEN REFUGE AND THE FIVE LAY VOWS TEACHINGS AND PRACTICES BY LAMA ZOPA RINPOCHE, ALEXANDER BERZIN COMPILED BY VEN. ROBINA COURTIN These teachings and prayers have been compiled by Robina Courtin, in various editions, since 2011. This latest version was done on November 25, 2016, at the Buddhist Retreat Centre, Ixopo, South Africa. Page 3 picture “This is Lama Yeshes Altar Carried Always With Him”: written by Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the frame, which is sitting on one of the altars in the Hayagriva Room at Tushita Retreat Centre in McLeod Ganj, Dharamsala, India. Photo Robina Courtin 3 CONTENTS ADVICE 1. Refuge and Lay Vows Lama Zopa Rinpoche 5 2. Actions to Adopt and Avoid Having Taken Refuge Alexander Berzin 11 3. The Ten Non-Virtuous Actions and Their Results 17 MORNING PRACTICES 4. Start the Day with Water Bowl Offerings 27 5. Daily Prayer of Refuge 29 6. Bless Your Speech 30 7. Recite Mantras for Creating Merit 34 8. Daily Motivation Lama Zopa Rinpoche 36 9. First Alternative Morning Practice: Refuge, Bodhichitta, Seven Limbs, etc. 44 10. Second Alternative Morning Practice: Meditation on Buddha Shakyamuni 48 11. Third Alternative Morning Practice: Meditation on Buddha Tara 53 12. Dedication Prayers 57 13. Long-life Prayers 59 DAILY PRACTICE 14. Bless Your Food and Offer It to the Three Jewels 61 EVENING PRACTICE 15. Purification: Vajrasattva in the Context of the Four Opponent Powers 62 4 1. REFUGE IN BUDDHA, DHARMA AND SANGHA AND THE FIVE LAY VOWS LAMA ZOPA RINPOCHE MOTIVATION FOR THE LIFE The purpose of my life is to free all sentient beings from every suffering and to lead them to happiness, especially the sublime peerless happiness of full enlightement.