This Is the Published Version: Available from Deakin Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REACHING OUT: a History of and Contemporary Look at the Centers, Projects and Services of FPMT

REACHINGOUT REACHING OUT: A history of and contemporary look at the Centers, Projects and Services of FPMT Lama Yeshe supervises building of Kopan FPMT pioneers: Peter Kedge, Lama Yeshe, Gompa extension, 1976 Sister Max1 and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, 1982 We make the ocean and the fish will come. – Lama Thubten Yeshe pi-o-neer: And funding? Lama Yeshe was brutal in his insistence 1. One who ventures into unknown or unclaimed that centers and students be self-sufficient and often territory to settle. encouraged them to start businesses. Lama’s early students 2. One who opens up new areas of thought, research or were made up of those from the anti-establishment genera- development. tion and many had been quite proud to cheat on their taxes, accept welfare payments, shoplift or sell marijuana as ama Thubten Yeshe (1935-1984), founder of the methods to remain on the fringes of society. Lama insisted Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana that his students “do what society people do” and function LTradition (FPMT), was many things to many people. as professional members of the world. Breaking the law or What seems a constant impression from those who knew following the “hippie” notion that money and capitalism him was that Lama Yeshe was big. “Think big,” “big love,” were necessary evils would get them nowhere. It was one’s – these are catch-phrases commonly attributed to Lama. motivation that corrupted ventures in commerce, and since Some students even claim he often appeared to physically his students were engaging in business practice to be of grow far bigger than his 5 ft 6 in (167 cm) frame. -

Teaching from the Vajrasattva Retreat Lama Zopa 1

TEACHINGS FROMTHE VAJRASATTVARETREAT Previously published by the LAMAYESHEWISDOMARCHIVE Becoming Your Own Therapist,by Lama Yeshe Advice for Monks and Nuns,by Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche Virtue and Reality, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Make Your Mind an Ocean,by Lama Yeshe Forthcoming (for initiates only) A Chat about Heruka,by Lama Zopa Rinpoche A Chat about Yamantaka,by Lama Zopa Rinpoche (Contact us for information.) May whoever sees, touches, reads, remembers, or talks or thinks about the above booklets or this book never be reborn in unfortunate circumstances, receive only rebirths in situations conducive to the perfect practice of Dharma, meet only perfectly qualified spiritual guides, quickly develop bodhicitta and immediately attain enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings. LAMAZOPARINPOCHE TEACHINGS FROMTHE VAJRASATTVARETREAT Land of Medicine Buddha, February–April, 1999 Edited by Ailsa Cameron and Nicholas Ribush LAMAYESHEWISDOMARCHIVE•BOSTON A non-profit charitable organization for the benefit of all sentient beings and a section of the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition www.fpmt.org First published 2000 LAMAYESHEWISDOMARCHIVE POBOX356 WESTON MA 02493, USA © Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche 2000 Please do not reproduce any part of this book by any means whatsoever without our permission. ISBN 1-891868-04-7 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Front cover: Vajrasattva, painted by Peter Iseli, photo by Ueli Minder Back cover photo of retreat group, April 30, 1999, by Bob Cayton Cover and interior design by Mark Gatter -

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts By Ramin Etesami A thesis submitted to the graduate school in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the International Buddhist College, Thailand March, 20 Abstract The Tulku institution is a unique characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism with a central role in this tradition, to the extent that it is present in almost every aspect of Tibet’s culture and tradition. However, despite this central role and the scope and diversity of the socio-religious aspects of the institution, only a few studies have so far been conducted to shed light on it. On the other hand, an aura of sacredness; distorted pictures projected by the media and film industries;political propaganda and misinformation; and tendencies to follow a pattern of cult behavior; have made the Tulku institution a highly controversial topic for research; and consequently, an objective study of the institution based on a critical approach is difficult. The current research is an attempt to comprehensively examine different dimensions of the Tulku tradition with an emphasis on the issue of its orthodoxy with respect to the core doctrines of Buddhism and the social implications of the practice. In this research, extreme caution has been practiced to firstly, avoid any kind of bias rooted in faith and belief; and secondly, to follow a scientific methodology in reviewing evidence and scriptures related to the research topic. Through a comprehensive study of historical accounts, core Buddhist texts and hagiographic literature, this study has found that while the basic Buddhist doctrines allow the possibility for a Buddhist teacher or an advanced practitioner to “return back to accomplish his tasks, the lack of any historical precedence which can be viewed as a typical example of the practice in early Buddhism makes the issue of its orthodoxy equivocal and relative. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY I. Primary Sources I. 1. Pāli and Sanśkrit Texts

BIBLIOGRAPHY I. Primary Sources I. 1. Pāli and Sanśkrit Texts Aṅguttara Nikāya, Ed. R. Morris & E. Hardy, 5 vols., London: PTS, 1885- 1900. Tr. F. L. Woodward, vols. I, II & V; E. M. Hare, vols. III & IV. The Book of the Gradual Sayings, London: PTS, 1955 – 1970. Avataṃsaka Sūtra, Tr. Thomas Cleary, the Flower Ornament Scripture, Shambhala – Boston & London, 1985. Bodhicaryāvatāra of Śāntideva, Commentary by Shri Prajñkaramati, Varanasi, India, Bauddha Bharati: 1988. Bodhicaryāvatāra of Śāntideva, Tr. Stephen Batchlor, A Guide to the Bodhisattva‘s Way of Life, New Delhi: 1998. Bodhicaryāvatāra of Śāntideva, Tr. The Padmakara Translation Group, The Way of The Bodhisattva, Boston: Shambhala, 1997. Bodhisattvabhūmi, Ed. N. Dutt, Vol. II, K. P. Jayaswal Research Institute, Patna: 1978. The Bodhisattvapiṭaka (Its Doctrines, Practices and their Position in Mahāyāna Literature), Ulrich Pagel, the Institute of Buddhist Studies, Tring, U. K.: 1995. Daśabhūmika Sūtra, Ed. Dr. P. L. Vaidya. Buddhist Sankrit Texts, No.7. Darbhanga, India: Mithila Sanśkrit Institute, 1976. 229 Dharmapada (Pāli Text and Translation), Tr. Ven. Nārada Maha Thera, Maha Bodhi Information and Publication Division, Maha Bodhi Society in India, Isipatana Deer Park, Sanarth Centre: 2000. The Dhammapada, Ed. K. Sri Dhammananda, Sasana Abhiwurdhi Society, Buddhist Vihara, Kuala Lumpur: 1992. Dīgha Nikāya, Ed. T. W. Rhys Davids & J.E. Carpenter, 3 vols., London: PTS, 1890-1911. Tr. T. W. & C.A.F. Rhys Davids; Dialogues of the Buddha, 3 vols., London: PTS, 1899, 1910 & 1957 respectively (reprints). Dipavamsa, Ed. Herman Oldenbery, New Delhi: 1982. Gandhavyūha Sūtra, Ed. Dr. P. L. Vaidya, Buddhist Sanśkrit Texts, No. 5. Darbhanga, Mithila Sanskrit Institute, India. -

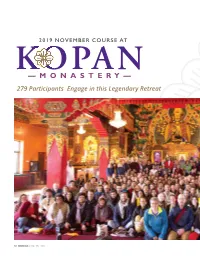

— M O N a S T E R

2019 NOVEMBER COURSE AT KOPAN —MONASTERY— 279 Participants Engage in this Legendary Retreat 52 MANDALA | Issue One 2020 Every year, the November Course, a month-long lamrim meditation course at Kopan Monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal, draws diverse students from around the world. What started in 1971 with a dozen students in attendance, reached a record 279 participants from forty-nine countries this year with Ven. Robina Courtin teaching the course for the first time. This was also the first course held in Kopan’s new Chenrezig gompa. Mandala editor, Carina Rumrill asked Ven. Robina about this year’s course, and we share this beautiful account of her experience and history with this style of retreat. THIS YEAR’S RECORD NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS — 279 PEOPLE FROM FORTY-NINE COUNTRIES — WITH KOPAN’S ABBOT KHEN RINPOCHE THUBTEN CHONYI, VEN. ROBINA COURTIN, AND OTHER TEACHERS AND MEDITATION LEADERS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). Issue One 2020 | MANDALA 53 VEN. ROBINA COURTIN OFFERED A MANDALA TO RINPOCHE REQUESTING TEACHINGS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). AND THE BLESSINGS: YOU COULDN’T HELP BUT FEEL THEM BY VEN. ROBINA COURTIN The Kopan November Course is legendary. The first of what But the beauty of the place was its saving grace: a hill became an annual event, one month of lamrim teachings by surrounded on all sides by the terraced fields of the magnifi cent Lama Zopa Rinpoche to a dozen Westerners fifty years ago, Kathmandu Valley, with mountains to the north and the holy quickly became a magnet for spiritual seekers worldwide. -

Medicine Buddha Interior Final.Indd

This book is published by Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive Bringing you the teachings of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche This book is made possible by kind supporters of the Archive who, like you, appreciate how we make these teachings freely available in so many ways, including in our website for instant reading, listening or downloading, and as printed and electronic books. Our website offers immediate access to thousands of pages of teachings and hundreds of audio recordings by some of the greatest lamas of our time. Our photo gallery and our ever-popular books are also freely accessible there. Please help us increase our efforts to spread the Dharma for the happiness and benefit of all beings. You can find out more about becoming a supporter of the Archive and see all we have to offer by visiting our website at http://www.LamaYeshe.com. Thank you so much, and please enjoy this ebook. Teachings from the Medicine Buddha Retreat Previously Published by the LAMA YESHE WISDOM ARCHIVE Becoming Your Own Therapist, by Lama Yeshe Advice for Monks and Nuns, by Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche Virtue and Reality, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Make Your Mind an Ocean, by Lama Yeshe Teachings from the Vajrasattva Retreat, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism, by Lama Yeshe Daily Purification: A Short Vajrasattva Practice, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Making Life Meaningful, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Teachings from the Mani Retreat, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Direct and Unmistaken Method, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Yoga of Offering Food, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche -

A Concise Set of Buddhist Healing Prayers and Practices – Preface

A Concise Set of Buddhist Healing Prayers and Practices revised edition by Jason Espada “It is said that whenever we practice Dharma it should always be pervaded by compassion at all times – in the beginning, in the middle and at the end of our practice. Compassion is the source, the real essence of the entire path.” - Khenpo Appey Rinpoche 1 Preface - I A Concise Set of Buddhist Healing Prayers and Practices – Preface In April of 2009, I was able to complete the first edition of A Collection of Buddhist Healing Prayers and Practices. That work contains background essays on the foundation of healing in Buddhism, as I understand it, as well as a good deal of supplementary material, such as Tibetan Buddhist Sadhanas (practice texts, or ‘methods of accomplishment’). I felt it was necessary to set the practices that are used for healing in their proper context, as part of Buddhist Tradition, and also to show how they can be used by someone today, in 21st century American culture. Over the last two years, I’ve written a few more essays, and some more poetry that I plan to include in later editions of that book. I’ve also continued to practice with a concise set of reflections, prayers and visualizations, that is relatively just a few pages. Almost as soon as I finished the first work I thought it would be good to have a brief text that can be used for daily practice, or that can be taken as a suggestion for another person who wants to draw together various prayers and practices for their own personal use. -

The Answer Was Travel, Serious Travel by Nick Ribush Dr

Your COMMUNITY THE ROAD TO KOPAN The Answer Was Travel, Serious Travel By Nick Ribush Dr. Nick Ribush was practicing medicine in Australia when, for various reasons, he got a bit disillusioned with it and, in May 1972, set off to travel the world. By the end of the year he was living at Kopan, beginning what is, at this point, an almost four-decade career within FPMT. “If at the time someone had told me what would happen to my life if I did that course,” he said, “I probably would not have done it!” Since then, he has, on behalf of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, founded and directed Wisdom Publications, Tushita Mahayana Meditation Centre, Kurukulla Center and the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive, which he has run for the past 15 years. Nick generously shared his story with Mandala as part of our ongoing feature, The Road to Kopan. Nick at Kopan Monastery, January 1973. Photo courtesy of Nick Ribush. 48 MANDALA July - September 2011 I was lying on my bed on the farm at Maleny, European hippies on their way to Australia to earn enough Queensland, when I noticed a lump in my left iliac fossa. money to either go back to India or get back home. It was a George Costanza moment: “Oh my god. My life is Eventually even paradise got boring, as it does, and we perfect and now I’m being punished with cancer.” That’s moved on to Java. Our first stop was a coffee plantation near the type of hypochondriac I was. -

Intimate Reflections

INTIMATEREFLECTIONS INTIMATE REFLECTIONS Twenty-five years after the passing of Lama Yeshe, students who were there in the early years remember their time with this extraordinary guru as if it were yesterday. This section is devoted to the intimate reflections of those early students, forever transformed by the guidance and care of their Lama. Step back with them as they recall the precious advice, the amusing stories, the first Kopan courses, Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa’s perfect partnership and the end of this particular dream when Lama Yeshe passed. here we were, about fifty out-of-control Westerners There were about a dozen hippies there. They were too Tfrom all over the world, strangers stuck together for freaky for me and I was sure if you turned them all upside a month, most of us listening to Dharma teachings for down you wouldn’t get more than one hundred dollars out the first time. Up at 5:00 A.M., out into the cold, to sit of the lot of them. cross-legged for an hour and a half’s meditation. A Peter Kedge, at the time a Rolls-Royce aeronautical engineer from England, on his experience at the second Kopan course, 1972. I fronted up feeling ill and dirty. Even the flower I presented to Lama Yeshe smelled bad. But when it was my turn to stand in front of him, something remarkable happened – my awful hangover disappeared and I felt incredibly clean and fresh. People told me I even looked younger. I will never forget that one smile he gave me and felt I really had taken refuge. -

Robina S&S Feature Template

Robina_S&S Feature Template 04/10/2013 09:59 Page 1 “If you don’t RESPECT YOURSELF, how can you expect others to?” Our new columnist, the venerable Robina Courtin is an outspoken, tough and fiery Buddhist nun. Each month she answers your questions concerning Buddhism in a modern world. Robina is teaching in London, Somerset, This month it’s how to respect YOU! Scotland, France, Denmark and Sweeden remember my mother would For sure, we do get angry, bad-mouth in November. say this phrase to me, but others, make a mess of our relationships, get See her schedule at I could never hear it. I would jealous, and the rest, and need to be robinacourtin.com. desperately want others to accountable for these parts of ourselves. But Iapprove of, love and respect me, we end up feeling guilty instead, and this is but I couldn’t join the dots between useless: it’s not about taking responsibility at that and my own low self-esteem. In all. It merely reinforces our low self-esteem, The Five Top Regrets of the Dying. She said and we believe it’s permanent, and that it is fact, I didn’t know what it meant! It the top regret was: ‘I wish I’d had the courage who we really are. seemed so true that I wasn’t worthy to live a life true to myself, not the one others expected of me’. or good enough. ON THE BRIGHT SIDE That’s the one! It’s huge, actually, but we This is the irony of the ego, according to the But we also do good things: work hard, have no choice. -

Recommended by Ven. Robina Courtin

Venerable Robina Recommends Venerable Robina Courtin has been a nun for 29 years in the Gelugpa tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and is a student of the FPMT’s Lama Zopa Rinpoche and Lama Yeshe. She spent 10 years editing for Wisdom Publications followed by over 5 years as the editor of Mandala, the magazine of the FPMT. Ven. Robina currently directs the Liberation Prison Project based in San Francisco serving hundreds of prisoners world-wide, and travels around the world teaching Buddhism at FPMT centers. She has been profiled in the award- winning documentary, Chasing Buddha. For more information visit the LPP website: www.LiberationPrisonProject.org Spiritual Friends Edited by Thubten Dondrub A collection of the favorite guided meditations of senior monks and nuns of the International Mahayana Institute of the FPMT. These meditations center on different Buddhist themes and provide a good resource for the practicing meditator. The book also includes brief spiritual autobiographies that allow the reader to trace each contributor’s entry into and study of Tibetan Buddhism. Destructive Emotions: How Can We Overcome Them? A Scientific Dialogue With the Dalai Lama by His Holiness the Dalai Lama & Daniel Goleman Imagine sitting with the Dalai Lama in his private meeting room with a small group of world-class scientists and philosophers. Although there are no easy answers, the dialogues, which are part of a series sponsored by the Mind and Life Institute, chart an ultimately hopeful course. They are sure to spark discussion among all people who seek peace for themselves and the world. Buddhism for Dummies by Jonathan Landlaw and Stephen Bodian How can the practice of Buddhism enrich our never-ending hectic lives? Discover what it means to be a Buddhist in everyday life and everyday lands in this fascinating Eastern religion. -

The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-Pa Formations

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-09-13 The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations Emory-Moore, Christopher Emory-Moore, C. (2012). The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28396 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/191 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-pa Formations by Christopher Emory-Moore A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2012 © Christopher Emory-Moore 2012 Abstract This thesis explores the adaptation of the Tibetan Buddhist guru/disciple relation by Euro-North American communities and argues that its praxis is that of a self-motivated disciple’s devotion to a perceptibly selfless guru. Chapter one provides a reception genealogy of the Tibetan guru/disciple relation in Western scholarship, followed by historical-anthropological descriptions of its practice reception in both Tibetan and Euro-North American formations.