Introduction Theoretical Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adobe Font Folio Opentype Edition 2003

Adobe Font Folio OpenType Edition 2003 The Adobe Folio 9.0 containing PostScript Type 1 fonts was replaced in 2003 by the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition ("Adobe Folio 10") containing 486 OpenType font families totaling 2209 font styles (regular, bold, italic, etc.). Adobe no longer sells PostScript Type 1 fonts and now sells OpenType fonts. OpenType fonts permit of encrypting and embedding hidden private buyer data (postal address, email address, bank account number, credit card number etc.). Embedding of your private data is now also customary with old PS Type 1 fonts, but here you can detect more easily your hidden private data. For an example of embedded private data see http://www.sanskritweb.net/forgers/lino17.pdf showing both encrypted and unencrypted private data. If you are connected to the internet, it is easy for online shops to spy out your private data by reading the fonts installed on your computer. In this way, Adobe and other online shops also obtain email addresses for spamming purposes. Therefore it is recommended to avoid buying fonts from Adobe, Linotype, Monotype etc., if you use a computer that is connected to the internet. See also Prof. Luc Devroye's notes on Adobe Store Security Breach spam emails at this site http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/legal.html Note 1: 80% of the fonts contained in the "Adobe" FontFolio CD are non-Adobe fonts by ITC, Linotype, and others. Note 2: Most of these "Adobe" fonts do not permit of "editing embedding" so that these fonts are practically useless. Despite these serious disadvantages, the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition retails presently (March 2005) at US$8,999.00. -

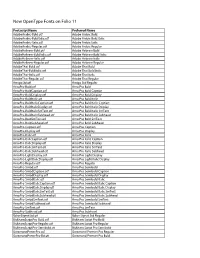

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

Kepler Italic

Brioso™ Pro a® a abcdefghijklmnopqrst An Adobe® Original Brioso Pro a umanistic Composition aily abcdefghijklmnopqrst © Adobe Systems Incorporated. Al rights reserved. uvwxyz For more information about OpenType please refer to Adobe’s web site at www.adobe.com/type/opentype. is document was designed to be viewed on-screen or printed duplex and assemled as a booklet. Adobe Originals Adobe Systems Incorporated introduces Brioso Pro, a new font soware package in the growing library of Adobe Originals typefaces, designed ecicaly for today’s digital technology. Since the inception of the Adobe Originals program in , Adobe Originals typefaces have been consistently recognized for their quality, originality, and praicality. They combine the power of PostScript® lanuage soware and the most sophisticated electronic design tools with the spirit of crasmanship that has inspired type designers since Gutenberg. Comprising both new designs and revivals of classic typefaces, Adobe Originals font soware has set a standard for typographic excelence. What is OpenType? Developed jointly by Adobe and Microso, OpenType is a highly versatile new font le format that represents a signicant advance in type functionality on Windows® and Mac OS computers. Perhaps most exciting for designers and typographers is that OpenType fonts offer extendedlayout features that bring unprecedented control and sophistication to contemporary typography. Because OpenType can incorporate al glyphs for a ecic style and weight into a single font, the need for separate expert, alternate, swash, non-Latin, and related glyph sets is eliminated. In aplications which suport OpenType layout features, such as Adobe’s InDesign® soware, glyphs are grouped according to their use. -

A Collection of Mildly Interesting Facts About the Little Symbols We Communicate With

Ty p o g raph i c Factettes A collection of mildly interesting facts about the little symbols we communicate with. Helvetica The horizontal bars of a letter are almost always thinner than the vertical bars. Minion The font size is approximately the measurement from the lowest appearance of any letter to the highest. Most of the time. Seventy-two points equals one inch. Fridge256 point Cochin most of 50the point Zaphino time Letters with rounded bottoms don’t sit on the baseline, but slightly below it. Visually, they would appear too high if they rested on the same base as the squared letters. liceAdobe Caslon Bold UNITED KINGDOM UNITED STATES LOLITA LOLITA In Ancient Rome, scribes would abbreviate et (the latin word for and) into one letter. We still use that abbreviation, called the ampersand. The et is still very visible in some italic ampersands. The word ampersand comes from and-per-se-and. Strange. Adobe Garamond Regular Adobe Garamond Italic Trump Mediaval Italic Helvetica Light hat two letters ss w it cam gue e f can rom u . I Yo t h d. as n b ha e rt en ho a s ro n u e n t d it r fo w r s h a u n w ) d r e e m d a s n o r f e y t e t a e r b s , a b s u d t e d e e n m t i a ( n l d o b s o m a y r S e - d t w A i e t h h t t , h d e n a a s d r v e e p n t m a o f e e h m t e a k i i l . -

Typeface Classification Serif Or Sans Serif?

Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Serif or Sans Serif? ABCDEFG ABCDEFG abcdefgo abcdefgo Adobe Jenson DIN Pro Book Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Typeface or font? ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Regular ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Italic TYPEFACE FAMILY ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Bold ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Bold Italic Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Timeline Blackletter Humanist Old Style Transitional Modern Bauhaus Digital (aka Venetian) sans serif 1450 1460- 1716- 1700- 1780- 1920- 1980-present 1470 1728 1775 1880 1960 Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif The model for the first movable types was Blackletter (also know as Block, Gothic, Fraktur or Old English), a heavy, dark, at times almost illegible — to modern eyes — script that was common during the Middle Ages. from I Love Typography http://ilovetypography.com/2007/11/06/type-terminology-humanist-2/ Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif Types based on blackletter were soon superseded by something a little easier Humanist (also refered to Venetian).. ABCDEFG ABCDEFG > abcdefg abcdefg Adobe Jenson Fette Fraktur Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif The Humanist types (sometimes referred to as Venetian) appeared during the 1460s and 1470s, and were modelled not on the dark gothic scripts like textura, but on the lighter, more open forms of the Italian humanist writers. The Humanist types were at the same time the first roman types. Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif Characteristics 1. -

A Brief History of Typefaces the Invention of Printing Movable Type Was Invented by Johannes Gutenberg in Fifteenth-Century Germany

A brief history of typefaces The invention of printing Movable type was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in fifteenth-century Germany. His typography took cues from the dark, dense handwriting of the period, called “blackletter.” The traditional storage of fonts in two cases, one for majuscules and one for minuscules, yielded the terms “uppercase” and “lowercase” still used today. Working in Venice in the late fifteenth century, Nicolas Jenson created letters that combined gothic calligraphic traditions with the new Italian taste for humanist handwriting, which were based on classical models. )ADMIT)HAVEHADALITTLEWORKDONE 2PCFSU4MJNCBDITUZMFE!DOBE+FOTPO BGUFS/JDPMBT+FOTPOTSPNBOUZQFT ANDTHEITALICSOF,UDOVICODEGLI!RRIGHI DSFBUFEJOmGUFFOUIDFOUVSZ*UBMZ )DONTLOOKADAYOVERFIVEHUNDRED DO) )ADMIT)HAVEHADALITTLEWORKDONE 2PCFSU4MJNCBDITUZMFE!DOBE+FOTPO BGUFS/JDPMBT+FOTPOTSPNBOUZQFT ANDTHEITALICSOF,UDOVICODEGLI!RRIGHI DSFBUFEJOmGUFFOUIDFOUVSZ*UBMZ )DONTLOOKADAYOVERFIVEHUNDRED DO) The Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius distributed inexpensive, small-format books in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries to a broad, international public. His books used italic types, a cursive form that economized printing by allowing more words to fit on a page. This page combines italic text with roman capitals. Integrated uppercase and lowercase typefaces. The quick brown fox ran over lazy d the lazy dog 2 or 3 times. ITC Garamond, 1976 The quick brown fox ran over the lazy d lazy dog 2 or 3 (2 or 3) times. Adobe Garamond, 1986 The quick brown fox ran over the lazy d lazy dog 2 or 3 (2 or 3) times. Garamond Premier Regular, 2005 Garamond typefaces, based on the Renaissance designs of Claude Garamond, sixteenth century Enlightenment and abstraction The painter and designer Geofroy Tory believed that the proportions of the alphabet should reflect the ideal human form. -

Experimental Typography: Process Documentation 1

New School University communication? A larger part of this question is: “Is Parsons School of Design typography a mean of reproduction or a mean of Communication Design Department expression?”This question has always been in the back of my head and I thought that there should be a Experimental Typography: possible experiment around this area. However, as I Process Documentation 1 was trying to form my thoughts into words and coming up with a defined experiment, I found that the idea was too vague and abstract. This did not 01:11:02:00 yield me any meaningful experiment. Initially, I thought that I can form some kind of a study / First Proposal experiment group and gather people who are not so aware of typography, but as it was pointed out in a Despite a very unstable start of this semester, on 4th class discussion, it seemed impossible to conduct of October, the students were able to present many that kind of experiments. I thought that it will be very diverse experiments to the class. After the first helpful if I could get some kind of a response from assignment – counting the number of typefaces in the class. the world – and also during the process, I was trying to think and scribble down my thoughts on typography. When Christian and I was brain storming to put together a conclusion for the first assignment, many interesting views and problems arose. The process and conclusion is documented and discussed in our papers. (“Experimental Typography: Number of Typefaces, Research Analysis and Interpretation”, Schmidt, C. -

The Case for Cross-Breeding Fonts Topics: Technologies That Permit Generating a New Typeface That Shares the Characteristics of Two Or More Parents

THE MAKEREADY ARCHIVE Column 5 of 77 The Case for Cross-Breeding Fonts Topics: Technologies that permit generating a new typeface that shares the characteristics of two or more parents. Column first appeared: April 1994, Computer Artist magazine. Source of this file: An expanded version of the column as it appeared in the 1996 book Makeready. Author's comment: The idea of morphed typefaces was one whose time never came. None of the products featured here have been available in the last ten years. Even Adobe's highly-touted Multiple Master tech- nology never made it into the mainstream. This archive, to be released over several years, collects the columns that Dan Margulis wrote under the Makeready title between 1993 and 2006. In some cases the columns appear as written; in others the archive contains revised versions that appeared in later books. Makeready in principle could cover anything related to graphic arts production, but it is best known for its contributions to Photoshop technique, particularly in the field of color correction. In its final years, the column was appearing in six different magazines worldwide (two in the United States). Dan Margulis teaches small-group master classes in color correction. Information is available at http://www.ledet.com/margulis, which also has a selection of other articles and chapters from Dan’s books, and more than a hundred edited threads from Dan’s Applied Color Theory e-mail list. Copyright© 1994, 1996, 2020 Dan Margulis. All rights reserved. 11 The Case for Cross-Breeding Fonts With tens of thousands of typefaces on the market, why in the world would one want to morph existing ones? The creative designer may find some reasons. -

Introduction to Graphic Design Lecture 2

Introduction to Graphic Design Lecture 2 Type Classifications Introduction to Graphic Design Lecture 2 font or typeface? A typeface is a set of typographical symbols and characters. It’s the letters, numbers, and other characters such as diacritical marks that let us put words on paper or screen. A font, on the other hand, is traditionally defined as a complete character set within a typeface, often of a particular size and style. When most of us talk about “fonts”, we’re really talking about typefaces, or type families (which are groups of typefaces with related designs). Introduction to Graphic Design Lecture 2 Circular Std. WEIGHTS / STYLES Book 17.5 pt Book Italic 17.5 pt Medium 17.5 pt Medium Italic 17.5 pt Bold 17.5 pt Bold Italic 17.5 pt Black 17.5 pt Black Italic 17.5 pt Introduction to Graphic Design Lecture 2 Typographic classifications are both historical and reflect typographic anatomy. Basic Type Classifications serif / sans serif / script / decorative Lyon Display Reg. serif Circular Std. Med. sans serif Snell Roundhand Blk. script Hobeaux Rococeaux decorative Basic Type Classifications serif / sans serif serif sans serif Serif typefaces are called “serifs” in reference to the small lines that are attached to the main strokes of characters within the face. Typefaces in this category are also known as Roman and are most commonly used for large bodies of text. Sans serif means “without serif” in French. The first sans serif typeface was issued in 1816, but these typefaces did not become popular until the early twentieth century. -

The Visibility and Legibility of Roman Typefaces: a Review with Blur Simulation

The Visibility and Legibility of Roman Typefaces: A Review with Blur Simulation * Rachapoom Punsongserm Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Thammasat University, Pathum Thani, Thailand Abstract Background According to our previous study, Thai Typefaces (Part 1): Assumption on Visibility and Legibility Problems, we examined underlying stages in the visibility and legibility matters of the Thai typefaces where the results have provided the assumption for developing the glyphs of the Thai universal design font (UD font). However, studying the visibility and legibility of Roman letters has still been a necessity, as it represents the international language. Developing high visibility and high legibility of the Roman typeface is requisite for supporting the Thai UD font as well. Methods The current study qualitatively initial tested the tolerance of Roman characters under blurred conditions. We applied seventy Roman fonts in the form of 'The Internal Relationship of Letters in the Feature Comparison Theory' in the same x-heights as stimuli, which simulated the low visual acuity at different blur levels. Results The simulated condition suggests significant advantages and disadvantages of each Roman type concerning visibility and legibility. The results improved ideas and possible solutions, which may assist with the approach of designing high-performance Roman letterforms that contribute to the Thai UD font as a Roman character set. Conclusions In order to improve the visibility and legibility of the Roman letterforms toward a UD font, the current pilot study conducted an investigation via blurred Roman types. The study revealed the advantages and disadvantages of several Roman letterforms, which suggest approaches to developing the Roman characters actively in low visual acuity conditions. -

Professional Typography with Adobe Indesign FOURTH EDITION Type

InDesignProfessional Typography with Adobe InDesign FOURTH EDITION Type Nigel French InDesign Type: Professional Typography with Adobe® InDesign®, Fourth Edition © 2018 Nigel French. All rights reserved. Adobe Press is an imprint of Pearson Education, Inc. For the latest on Adobe Press books, go to www.adobepress.com. To report errors, please send a note to [email protected]. For information regarding permissions, request forms and the appropriate contacts within the Pearson Education Global Rights & Permissions department, please visit www.pearsoned.com/permissions/. The content of this guide is furnished for informational use only, is subject to change without notice, and should not be construed as a commitment by Adobe Systems Incorporated. Adobe Systems Incorporated assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or inaccuracies that may appear in the informational content contained in this guide. Please remember that existing artwork or images that you may want to include in your project may be protected under copyright law. The unauthorized incorporation of such material into your new work could be a violation of the rights of the copyright owner. Please be sure to obtain any permission required from the copyright owner. Any references to company names in sample files are for demonstration purposes only and are not intended to refer to any actual organization. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Creative Cloud, the Creative Cloud logo, InDesign, and Photoshop are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. Adobe product screenshots reprinted with permission from Adobe Systems Incorporated. Apple, Mac OS, macOS, and Macintosh are trademarks of Apple, registered in the U.S. -

Adobe® Font Name Reference Table (Fntnames.Pdf)

® Adobe® Font Name Reference Table (Fntnames.pdf) © 1997 Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. ® Contents Typeface Trademark Symbols . 3 Introduction . 7 Font Name Reference Table . 11 Package 100 . 25 Package 200 . 42 Package 300 . 57 Package 400 . 74 Appendix A: Font Menu Name Revisions . 82 Appendix B: Trademark Attribution Statements . 91 Adobe Technical Support Technical Adobe ® Typeface Trademark Symbols The following list of trademark attribution symbols is arranged alpha- betically by family name. The name of the originating company (e.g., ITC) and prefixes such as “new” in names like “New Baskerville” were not used for alphabetizing. The trademark attribution statements are in Appendix B of this document. A Aachen™, Agfa®, Aja®, Berthold® Akzidenz Grotesk®, Albertus®, Aldus*, Alexa®, ITC American Typewriter®, Americana®, Amigo™, Andreas™, ITC Anna®, Antique Olive®, Apollo™, Arcadia*, Ariadne*, Arnold Bocklin*, Ashley Script™, New Aster™, Auriol*, ITC Avant Garde Gothic®, Avenir* B Baker Signet™, Balzano™, Banco®, Banshee™, Barmeno™, Berthold Baskerville™, Berthold Baskerville Book®, ITC New Baskerville®, ITC Bauhaus®, ITC Beesknees®, Bellevue™, Belwe™, Bembo®, ITC Benguiat®, ITC Benguiat Gothic®, ITC Berkeley Old Style®, Berliner Grotesk™, Berling™, Bermuda™, Bernhard Bold Condensed*, New Berolina™, Berthold®, Bickham Script™, Biffo™, Birch®, Blackoak®, Block Berthold®, Bauer Bodoni™, Berthold Bodoni®, Berthold Bodoni Old Face™, AG Book™, ITC Bookman®, Boton®, Boulevard™, Briem®, Bulmer™ C PMN Caecilia*, Caflisch Script®,