Professional Typography with Adobe Indesign FOURTH EDITION Type

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art, Philosophy, and the Philosophy Of

NATIONAL E N D O W M E N T FOR THE HUMANITIES VOLUME 4 NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY 1983 Humanities Art, Philosophy, and the Philosophy of Art period of Abstract Expressionism, ward behavior might be indistin when decisions for or against The guishable between the two. In all these Image were fraught with an almost cases one must seek the differences religious agony, the crass and casual outside the juxtaposed and puzzling use of tacky images by the new examples, and this is no less the case artists seemed irreverent and juve when seeking to account for the dif nile. But the Warhol show raised a ferences between works of art and question which was intoxicating and mere real things which happen immediately philosophical, namely exactly to resemble them. why were his boxes works of art This problem could have been while the almost indistinguishable raised at any time, and not just with utilitarian cartons were merely con the somewhat minimal sorts of tainers for soap pads? Certainly the works one might suspect the Brillo minor observable differences could Boxes to be. It was always conceiva not ground as grand a distinction as ble that exact counterparts to the that between Art and Reality! most prized and revered works of BY ARTHUR C. DANTO A philosophical question arises art could have come about in ways Not very many years ago, whenever we have two objects inconsistent with their being works aesthetics—understood as the phi which seem in every relevant par at all, though no observable differ losophy of art—was regarded as the ticular to be alike, but which belong ences could be found. -

The Hanging Package∗

The hanging package∗ Author: Peter Wilson, Herries Press Maintainer: Will Robertson will dot robertson at latex-project dot org 2009/09/02 Abstract The hanging package provides facilities for defining hanging paragraphs and hanging punctuation. Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 The hanging package 2 2.1 Hanging paragraphs . 2 2.2 Hanging punctuation . 2 3 The package code 3 3.1 Hanging paragraphs . 4 3.2 Hanging punctuation . 4 1 Introduction Some authors may wish to use hanging paragraphs in their documents. Normally only the first line of a paragraph is indented. A hanging paragraph is a paragraph like this one where lines other than the first have indentation. Other au- thors might wish to use hanging punctuation. In this style of typesetting punctuation marks that come at either the start or end of a line are typeset outside the normal text block. The hanging package provides facilities for both hanging paragraphs and hang- ing punctuation. This manual is typeset according to the conventions of the LATEX doc- strip utility which enables the automatic extraction of the LATEX macro source files [GMS94]. ∗This file (hanging.dtx) has version number v1.2b, last revised 2009/09/02. 1 Section 2 describes the usage of the package. Commented source code for the package is in Section 3. 2 The hanging package 2.1 Hanging paragraphs The hanging package provides a command for producing a single hanging para- graph and an environment for typesetting a series of hanging paragraphs. \hangpara The command \hangpara{hindenti}{hafternumi} placed at the start of a para- graph will cause it to be typeset as a hanging paragraph. -

The Etbb Package—Edward Tufte's Version of Bembo

The ETbb package—Edward Tufte’s version of Bembo Michael Sharpe Background The fonts in this package were derived ultimately from the collection of fonts commissioned by Edward Tufte for his own books, and released in 2015 as ET-Bembo under the MIT license. (The sources for that collection were fonts using the family name ET-book.) That collection was enhanced in 2019 under the name XETBook by Daniel Benjamin Miller, and it is his package which was the starting point for ETbb, where the bb denotes the Berry abbreviation for Bembo. The final section of this document makes a detailed comparison with the earlier fbb package, which is also Bembo-like, derived from Cardo. The most significant differences are that ETbb has a regular upright that is about 20% darker than the corre- sponding fbb, and its ascender height is noticeably less. These differences make ETbb have a less spindly appearance that is closer in spirit to the print produced by traditional metal versions of Bembo. Package properties The package makes a number of changes to the XETBook fonts: • The released version of ET-Bembo lacks kerning tables—a serious omission—rectified in ETbb. • The scale has been increased by 3.36% so that the x-height of the upright regular face is 431, very close to Computer Modern and Libertine. • The lining figures in some faces were reduced so as to be a bit less than the cap-heights. • The lining figures in XETBook were proportional rather than tabular. I’ve added new tabular lining and old-style figures. -

Paratext in Bible Translations with Special Reference to Selected Bible Translations Into Beninese Languages

DigitalResources SIL eBook 58 ® Paratext in Bible Translations with Special Reference to Selected Bible Translations into Beninese Languages Geerhard Kloppenburg Paratext in Bible Translations with Special Reference to Selected Bible Translations into Beninese Languages Geerhard Kloppenburg SIL International® 2013 SIL e-Books 58 2013 SIL International® ISSN: 1934-2470 Fair-Use Policy: Books published in the SIL e-Books (SILEB) series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes free of charge (within fair-use guidelines) and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Editor-in-Chief Mike Cahill Compositor Margaret González VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT AMSTERDAM PARATEXT IN BIBLE TRANSLATIONS WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO SELECTED BIBLE TRANSLATIONS INTO BENINESE LANGUAGES THESIS MASTER IN LINGUISTICS (BIBLE TRANSLATION) THESIS ADVISOR: DR. L.J. DE VRIES GEERHARD KLOPPENBURG 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 The phenomenon of paratext............................................................................................ 3 1.2 The purpose of this study ................................................................................................. 5 2. PARATEXT: DEFINITION AND DESCRIPTION............................................................. -

Adobe Font Folio Opentype Edition 2003

Adobe Font Folio OpenType Edition 2003 The Adobe Folio 9.0 containing PostScript Type 1 fonts was replaced in 2003 by the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition ("Adobe Folio 10") containing 486 OpenType font families totaling 2209 font styles (regular, bold, italic, etc.). Adobe no longer sells PostScript Type 1 fonts and now sells OpenType fonts. OpenType fonts permit of encrypting and embedding hidden private buyer data (postal address, email address, bank account number, credit card number etc.). Embedding of your private data is now also customary with old PS Type 1 fonts, but here you can detect more easily your hidden private data. For an example of embedded private data see http://www.sanskritweb.net/forgers/lino17.pdf showing both encrypted and unencrypted private data. If you are connected to the internet, it is easy for online shops to spy out your private data by reading the fonts installed on your computer. In this way, Adobe and other online shops also obtain email addresses for spamming purposes. Therefore it is recommended to avoid buying fonts from Adobe, Linotype, Monotype etc., if you use a computer that is connected to the internet. See also Prof. Luc Devroye's notes on Adobe Store Security Breach spam emails at this site http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/legal.html Note 1: 80% of the fonts contained in the "Adobe" FontFolio CD are non-Adobe fonts by ITC, Linotype, and others. Note 2: Most of these "Adobe" fonts do not permit of "editing embedding" so that these fonts are practically useless. Despite these serious disadvantages, the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition retails presently (March 2005) at US$8,999.00. -

Goldsmiths Research Online

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Goldsmiths Research Online GOLDSMITHS Research Online Article (refereed) Mukhopadhyay, Bhaskar Dream kitsch – folk art, indigenous media and '9/11': The Work of Pat in the Era of Electronic Transmission Originally published in Journal of Material Culture Copyright Sage. The publisher's version is available at: http://mcu.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/13/1/5 Please cite the publisher's version. You may cite this version as: Mukhopadhyay, Bhaskar, 2008. Dream kitsch – folk art, indigenous media and '9/11': The Work of Pat in the Era of Electronic Transmission. Journal of Material Culture, 13 (1). pp. 5-34. ISSN 1460-3586 [Article]: Goldsmiths Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.gold.ac.uk/2371/ This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during peer review. Some differences between this version and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. http://eprints-gro.goldsmiths.ac.uk Contact Goldsmiths Research Online at: [email protected] Dream kitsch – folk art, indigenous media and ‘9/11’: The work of pat in the era of electronic transmission Bhaskar Mukhopadhyay This article explores the process of transmission of the image(s) of 9/11 through an ethnographic/art-historical examination of Bengali (Indian) pat (traditional scroll painting) made by a community of rural Indian artisans with little or no exposure to mass-media. -

Dissertation Body Text FINAL SUBMISSION VERSION

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Openness to the Development of the Relationship: A Theory of Close Relationships Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2030n6jk Author Page, Emily Publication Date 2021 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Openness to the Development of the Relationship: A Theory of Close Relationships A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy by Emily Page 2021 © Copyright by Emily Page 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Openness to the Development of the Relationship: A Theory of Close Relationships by Emily Page Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor Alexander Jacob Julius, Chair In a word, this dissertation is about friendship. I begin by raising a problem related to one traditionally found within some of the philosophical literature regarding moral egalitarianism: that of partiality and friendship, except that I raise the issue of partiality within the context of one’s close relationships. From here I propose a solution to the problem based on understanding a close relationship as one in which friends possess the attitude of openness to the development of the relationship. The remainder of the dissertation is concerned with elaborating upon and explaining this conception of friendship and its consequences. In the course of doing this I propose a theory of the self and how we relate to one another, consider the importance of the psychophysical self, explore the notion of mutual recognition, reflect on relationship’s end, and, finally, explore the connections between friendship and play. -

The Eye Has It: Optical Alignment and Hanging Punctuation Sometimes Little Things Can Make a Big Difference

InType: Alignment By Nigel French The Eye Has It: Optical Alignment and Hanging Punctuation Sometimes little things can make a big difference. When it comes to typography this is especially true. One of the simplest enhancements you can make to your type— especially if you’re working with justified type—is to use Optical Margin Alignment. What is Optical Margin Alignment? But today, with InDesign’s Optical Have you ever noticed how punctuation Margin Alignment, we can easily ensure at the margin of a text frame can make the that punctuation, as well as the edges of left or right sides of a column appear mis- letters, hangs outside the text frame or aligned? When a line begins with punctua- column margins so that the column edge T tion, like an opening quotation mark, or remains flush (Figure 1). ends with a comma, period, or hyphen, you This makes Optical Margin Alignment get a visual hole. Once, this was regarded as especially beneficial when working with the price of progress. We could do so much justified text, but even with left-aligned more with our page layout programs—did text, the first character of the line will “hang” Figure 1: The text is the same; the margin alignment is not. it matter that we had to forgo a few niceties? outside the text frame. INDESIGN MAGAZINE 43 August | September 2011 CONTENTS PREVIOUS NEXT FULL SCREEN 30 InType: Alignment T Optical margin alignment isn’t to eve- tool, choose Story from the ryone’s taste. Some consider the look of Type menu, check the box optically aligned text too fussy, preferring and you’re good to go. -

Adobe Trademark Database for General Distribution

Adobe Trademark List for General Distribution As of May 17, 2021 Please refer to the Permissions and trademark guidelines on our company web site and to the publication Adobe Trademark Guidelines for third parties who license, use or refer to Adobe trademarks for specific information on proper trademark usage. Along with this database (and future updates), they are available from our company web site at: https://www.adobe.com/legal/permissions/trademarks.html Unless you are licensed by Adobe under a specific licensing program agreement or equivalent authorization, use of Adobe logos, such as the Adobe corporate logo or an Adobe product logo, is not allowed. You may qualify for use of certain logos under the programs offered through Partnering with Adobe. Please contact your Adobe representative for applicable guidelines, or learn more about logo usage on our website: https://www.adobe.com/legal/permissions.html Referring to Adobe products Use the full name of the product at its first and most prominent mention (for example, “Adobe Photoshop” in first reference, not “Photoshop”). See the “Preferred use” column below to see how each product should be referenced. Unless specifically noted, abbreviations and acronyms should not be used to refer to Adobe products or trademarks. Attribution statements Marking trademarks with ® or TM symbols is not required, but please include an attribution statement, which may appear in small, but still legible, print, when using any Adobe trademarks in any published materials—typically with other legal lines such as a copyright notice at the end of a document, on the copyright page of a book or manual, or on the legal information page of a website. -

Arno Pro Release Notes

Arno Pro Release Notes Introduction Named after the Florentine river which runs through the heart of the Italian Renaissance, Arno draws on the warmth and readability of early humanist typefaces of the 15th and 16th centuries. While inspired by the past, Arno is distinctly contemporary in both appearance and function. Designed by Adobe Principal Designer Robert Slimbach, Arno is a meticulously-crafted face in the tradition of early Venetian and Aldine book types. Embodying themes Slimbach has explored in typefaces such as Minion and Brioso, Arno represents a distillation of his design ideals and a refinement of his craft. As a multi-featured OpenType family, with the most extensive Latin-based glyph complement Adobe has yet offered, Arno offers extensive pan-European language support, including Cyrillic and poly- tonic Greek. The family also offers such typographic niceties as five optical size ranges, extensive swash italic sets, and small capitals for all covered languages. OpenType® OpenType “.otf” fonts are compact single-file cross-platform fonts, which can have extended language support based on Unicode, and enhanced typographic layout features. For OpenType information, including the OpenType User Guide, the OpenType Readme (application compatibility notes), and OpenType Specimen Book PDFs, visit Adobe’s Web site at http://www.adobe.com/type/opentype. About optical sizes Typefaces with optical size variants have had their designs subtly adjusted for use at specific point size ranges. This capability reintroduces one of the features of hand-cut metal type, which uses a separate font for each point size and is often optically adjusted. This is an advantage over the current common practice of scaling a single digital type design to different point sizes, which may reduce legibility at smaller sizes or sacrifice subtlety at larger sizes. -

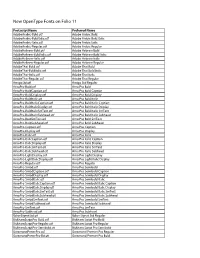

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

Vision Performance Institute

Vision Performance Institute Technical Report Individual character legibility James E. Sheedy, OD, PhD Yu-Chi Tai, PhD John Hayes, PhD The purpose of this study was to investigate the factors that influence the legibility of individual characters. Previous work in our lab [2], including the first study in this sequence, has studied the relative legibility of fonts with different anti- aliasing techniques or other presentation medias, such as paper. These studies have tested the relative legibility of a set of characters configured with the tested conditions. However the relative legibility of individual characters within the character set has not been studied. While many factors seem to affect the legibility of a character (e.g., character typeface, character size, image contrast, character rendering, the type of presentation media, the amount of text presented, viewing distance, etc.), it is not clear what makes a character more legible when presenting in one way than in another. In addition, the importance of those different factors to the legibility of one character may not be held when the same set of factors was presented in another character. Some characters may be more legible in one typeface and others more legible in another typeface. What are the character features that affect legibility? For example, some characters have wider openings (e.g., the opening of “c” in Calibri is wider than the character “c” in Helvetica); some letter g’s have double bowls while some have single (e.g., “g” in Batang vs. “g” in Verdana); some have longer ascenders or descenders (e.g., “b” in Constantia vs.