The Case for Cross-Breeding Fonts Topics: Technologies That Permit Generating a New Typeface That Shares the Characteristics of Two Or More Parents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department A GLOSSARY OF TERMS FOR FORMATTING COMPUTER-GENERATED BRIEFS, WITH EXAMPLES The rules concerning the formatting of briefs are contained in CPLR 5529 and in § 1250.8 of the Practice Rules of the Appellate Division. Those rules cover technical matters and therefore use certain technical terms which may be unfamiliar to attorneys and litigants. The following glossary is offered as an aid to the understanding of the rules. Typeface: A typeface is a complete set of characters of a particular and consistent design for the composition of text, and is also called a font. Typefaces often come in sets which usually include a bold and an italic version in addition to the basic design. Proportionally Spaced Typeface: Proportionally spaced type is designed so that the amount of horizontal space each letter occupies on a line of text is proportional to the design of each letter, the letter i, for example, being narrower than the letter w. More text of the same type size fits on a horizontal line of proportionally spaced type than a horizontal line of the same length of monospaced type. This sentence is set in Times New Roman, which is a proportionally spaced typeface. Monospaced Typeface: In a monospaced typeface, each letter occupies the same amount of space on a horizontal line of text. This sentence is set in Courier, which is a monospaced typeface. Point Size: A point is a unit of measurement used by printers equal to approximately 1/72 of an inch. -

Typography One Typeface Classification Why Classify?

Typography One typeface classification Why classify? Classification helps us describe and navigate type choices Typeface classification helps to: 1. sort type (scholars, historians, type manufacturers), 2. reference type (educators, students, designers, scholars) Approximately 250,000 digital typefaces are available today— Even with excellent search engines, a common system of description is a big help! classification systems Many systems have been proposed Francis Thibaudeau, 1921 Maximillian Vox, 1952 Vox-ATypI, 1962 Aldo Novarese, 1964 Alexander Lawson, 1966 Blackletter Venetian French Dutch-English Transitional Modern Sans Serif Square Serif Script-Cursive Decorative J. Ben Lieberman, 1967 Marcel Janco, 1978 Ellen Lupton, 2004 The classification system you will learn is a combination of Lawson’s and Lupton’s systems Black Letter Old Style serif Transitional serif Modern Style serif Script Cursive Slab Serif Geometric Sans Grotesque Sans Humanist Sans Display & Decorative basic characteristics + stress + serifs (or lack thereof) + shape stress: where the thinnest parts of a letter fall diagonal stress vertical stress no stress horizontal stress Old Style serif Transitional serif or Slab Serif or or reverse stress (Centaur) Modern Style serif Sans Serif Display & Decorative (Baskerville) (Helvetica) (Edmunds) serif types bracketed serifs unbracketed serifs slab serifs no serif Old Style Serif and Modern Style Serif Slab Serif or Square Serif Sans Serif Transitional Serif (Bodoni) or Egyptian (Helvetica) (Baskerville) (Rockwell/Clarendon) shape Geometric Sans Serif Grotesk Sans Serif Humanist Sans Serif (Futura) (Helvetica) (Gill Sans) Geometric sans are based on basic Grotesk sans look precisely drawn. Humanist sans are based on shapes like circles, triangles, and They have have uniform, human writing. -

Basic Styles of Lettering for Monuments and Markers.Indd

BASIC STYLES OF LETTERING FOR MONUMENTS AND MARKERS Monument Builders of North America, Inc. AA GuideGuide ToTo TheThe SelectionSelection ofof LETTERINGLETTERING From primitive times, man has sought to crude or garish or awkward letters, but in communicate with his fellow men through letters of harmonized alphabets which have symbols and graphics which conveyed dignity, balance and legibility. At the same meaning. Slowly he evolved signs and time, they are letters which are designed to hieroglyphics which became the visual engrave or incise cleanly and clearly into expression of his language. monumental stone, and to resist change or obliteration through year after year of Ultimately, this process evolved into the exposure. writing and the alphabets of the various tongues and civilizations. The early scribes The purpose of this book is to illustrate the and artists refi ned these alphabets, and the basic styles or types of alphabets which have development of printing led to the design been proved in memorial art, and which are of alphabets of related character and ready both appropriate and practical in the lettering readability. of monuments and markers. Memorial art--one of the oldest of the arts- Lettering or engraving of family memorials -was among the fi rst to use symbols and or individual markers is done today with “letters” to inscribe lasting records and history superb fi delity through the use of lasers or the into stone. The sculptors and carvers of each sandblast process, which employs a powerful generation infl uenced the form of letters and stream or jet of abrasive “sand” to cut into the numerals and used them to add both meaning granite or marble. -

Type ID and History

History and Identification of Typefaces with your host Ted Ollier Bow and Arrow Press Anatomy of a Typeface: The pieces of letterforms apex cap line serif x line ear bowl x height counter baseline link loop Axgdecender line ascender dot terminal arm stem shoulder crossbar leg decender fkjntail Anatomy of a Typeface: Design decisions Stress: Berkeley vs Century Contrast: Stempel Garamond vs Bauer Bodoni oo dd AAxx Axis: Akzidenz Grotesk, Bembo, Stempel Garmond, Meridien, Stymie Q Q Q Q Q Typeface history: Blackletter Germanic, completely pen-based forms Hamburgerfonts Alte Schwabacher c1990 Monotype Corporation Hamburgerfonts Engraver’s Old English (Textur) 1906 Morris Fuller Benton Hamburgerfonts Fette Fraktur 1850 Johan Christian Bauer Hamburgerfonts San Marco (Rotunda) 1994 Karlgeorg Hoefer, Alexei Chekulayev Typeface history: Humanist Low contrast, left axis, “penned” serifs, slanted “e”, small x-height Hamburgerfonts Berkeley Old Style 1915 Frederic Goudy Hamburgerfonts Centaur 1914 Bruce Rogers after Nicolas Jenson 1469 Hamburgerfonts Stempel Schneidler 1936 F.H.Ernst Schneidler Hamburgerfonts Adobe Jenson 1996 Robert Slimbach after Nicolas Jenson 1470 Typeface history: Old Style Medium contrast, more vertical axis, fewer “pen” flourishes Hamburgerfonts Stempel Garamond 1928 Stempel Type Foundry after Claude Garamond 1592 Hamburgerfonts Caslon 1990 Carol Twombley after William Caslon 1722 Hamburgerfonts Bembo 1929 Stanley Morison after Francesco Griffo 1495 Hamburgerfonts Janson 1955 Hermann Zapf after Miklós Tótfalusi Kis 1680 Typeface -

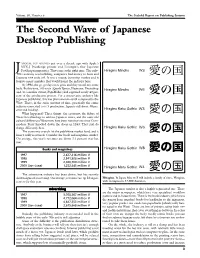

The Second Wave of Japanese Desktop Publishing

Volume 30, Number 6 The Seybold Report on Publishing Systems The Second Wave of Japanese Desktop Publishing APANESE DTP ARRIVED just over a decade ago with Apple’s NTX-J PostScript printer and Linotype’s first Japanese J PostScript imagesetter. They came at the right time: The early- ’90s economy was bubbling, companies had money to burn and Japanese DTP took off. It was a young, booming market and it forgave many mistakes that would haunt the industry later. By 1996, the go-go days were gone and they would not come back. By this time, DTP tools (Quark Xpress, Illustrator, Photoshop and, to a smaller extent, PageMaker) had captured nearly 40 per- cent of the production process. For a conservative industry like Japanese publishing, this was phenomenal—until compared to the West. There, in the same amount of time, practically the entire industry converted to DTP production. Japan is still about 40 per- cent and holding. What happened? Three things: the economy, the failure of Western technology to address Japanese issues, and the same old cultural differences Westerners have been running into since Com- modore Perry knocked down the doors in 1853. They just do things differently here. The economic crunch hit the publishing market hard, and it hasn’t really recovered. Consider the book and magazine market: On average, this year’s revenues are down 3.4 percent over last year. Books and magazines 1997 2,637,416 million ¥ 1998 2,541,508 million ¥ 1999 2,460,700 million ¥ 2000 (Jan–June) 1,232,445 million ¥ The advertising industry has been down, but has recently shown signs of recovering: On average, revenues are up 10.4 per- Hiragino. -

Adobe Font Folio Opentype Edition 2003

Adobe Font Folio OpenType Edition 2003 The Adobe Folio 9.0 containing PostScript Type 1 fonts was replaced in 2003 by the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition ("Adobe Folio 10") containing 486 OpenType font families totaling 2209 font styles (regular, bold, italic, etc.). Adobe no longer sells PostScript Type 1 fonts and now sells OpenType fonts. OpenType fonts permit of encrypting and embedding hidden private buyer data (postal address, email address, bank account number, credit card number etc.). Embedding of your private data is now also customary with old PS Type 1 fonts, but here you can detect more easily your hidden private data. For an example of embedded private data see http://www.sanskritweb.net/forgers/lino17.pdf showing both encrypted and unencrypted private data. If you are connected to the internet, it is easy for online shops to spy out your private data by reading the fonts installed on your computer. In this way, Adobe and other online shops also obtain email addresses for spamming purposes. Therefore it is recommended to avoid buying fonts from Adobe, Linotype, Monotype etc., if you use a computer that is connected to the internet. See also Prof. Luc Devroye's notes on Adobe Store Security Breach spam emails at this site http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/legal.html Note 1: 80% of the fonts contained in the "Adobe" FontFolio CD are non-Adobe fonts by ITC, Linotype, and others. Note 2: Most of these "Adobe" fonts do not permit of "editing embedding" so that these fonts are practically useless. Despite these serious disadvantages, the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition retails presently (March 2005) at US$8,999.00. -

Font HOWTO Font HOWTO

Font HOWTO Font HOWTO Table of Contents Font HOWTO......................................................................................................................................................1 Donovan Rebbechi, elflord@panix.com..................................................................................................1 1.Introduction...........................................................................................................................................1 2.Fonts 101 −− A Quick Introduction to Fonts........................................................................................1 3.Fonts 102 −− Typography.....................................................................................................................1 4.Making Fonts Available To X..............................................................................................................1 5.Making Fonts Available To Ghostscript...............................................................................................1 6.True Type to Type1 Conversion...........................................................................................................2 7.WYSIWYG Publishing and Fonts........................................................................................................2 8.TeX / LaTeX.........................................................................................................................................2 9.Getting Fonts For Linux.......................................................................................................................2 -

Choosing Fonts – Quick Tips

Choosing Fonts – Quick Tips 1. Choose complementary fonts – choose a font that matches the mood of your design. For business cards, it is probably best to choose a classic font. *Note: These fonts are not available in Canva, but are in the Microsoft Office Suite. For some good Canva options, go to this link – https://www.canva.com/learn/canva-for-work-brand-fonts/ Examples: Serif Fonts: Sans Serif Fonts: Times New Roman Helvetica Cambria Arial Georgia Verdana Courier New Calibri Century Schoolbook 2. Establish a visual hierarchy – Use fonts to separate different types of information and guide the reader - Use different fonts, sizes, weights (boldness), and even color - Example: Heading (Helvetica, SZ 22, Bold) Sub-heading (Helvetica, SZ 16, Italics) Body Text (Garamond, SZ 12, Regular) Captions (Garamond, SZ 10, Regular 3. Mix Serifs and Sans Serifs – This is one of the best ways to add visual interest to type. See in the above example how I combined Helvetica, a sans serif font, with Garamond, a serif font. 4. Create Contrast, Not Conflict: Fonts that are too dissimilar may not pair well together. Contrast is good, but fonts need a connecting element. Conflict Contrast 5. Use Fonts from the Same Family: These fonts were created to work together. For example, the fonts in the Arial or Courier families. 6. Limit Your Number of Fonts: No more than 2 or 3 is a good rule – for business cards, choose 2. 7. Trust Your Eye: These are not concrete rules – you will know if a design element works or not! . -

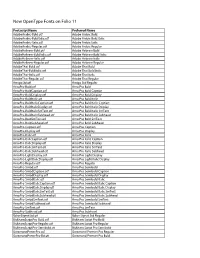

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

Kepler Italic

Brioso™ Pro a® a abcdefghijklmnopqrst An Adobe® Original Brioso Pro a umanistic Composition aily abcdefghijklmnopqrst © Adobe Systems Incorporated. Al rights reserved. uvwxyz For more information about OpenType please refer to Adobe’s web site at www.adobe.com/type/opentype. is document was designed to be viewed on-screen or printed duplex and assemled as a booklet. Adobe Originals Adobe Systems Incorporated introduces Brioso Pro, a new font soware package in the growing library of Adobe Originals typefaces, designed ecicaly for today’s digital technology. Since the inception of the Adobe Originals program in , Adobe Originals typefaces have been consistently recognized for their quality, originality, and praicality. They combine the power of PostScript® lanuage soware and the most sophisticated electronic design tools with the spirit of crasmanship that has inspired type designers since Gutenberg. Comprising both new designs and revivals of classic typefaces, Adobe Originals font soware has set a standard for typographic excelence. What is OpenType? Developed jointly by Adobe and Microso, OpenType is a highly versatile new font le format that represents a signicant advance in type functionality on Windows® and Mac OS computers. Perhaps most exciting for designers and typographers is that OpenType fonts offer extendedlayout features that bring unprecedented control and sophistication to contemporary typography. Because OpenType can incorporate al glyphs for a ecic style and weight into a single font, the need for separate expert, alternate, swash, non-Latin, and related glyph sets is eliminated. In aplications which suport OpenType layout features, such as Adobe’s InDesign® soware, glyphs are grouped according to their use. -

A Collection of Mildly Interesting Facts About the Little Symbols We Communicate With

Ty p o g raph i c Factettes A collection of mildly interesting facts about the little symbols we communicate with. Helvetica The horizontal bars of a letter are almost always thinner than the vertical bars. Minion The font size is approximately the measurement from the lowest appearance of any letter to the highest. Most of the time. Seventy-two points equals one inch. Fridge256 point Cochin most of 50the point Zaphino time Letters with rounded bottoms don’t sit on the baseline, but slightly below it. Visually, they would appear too high if they rested on the same base as the squared letters. liceAdobe Caslon Bold UNITED KINGDOM UNITED STATES LOLITA LOLITA In Ancient Rome, scribes would abbreviate et (the latin word for and) into one letter. We still use that abbreviation, called the ampersand. The et is still very visible in some italic ampersands. The word ampersand comes from and-per-se-and. Strange. Adobe Garamond Regular Adobe Garamond Italic Trump Mediaval Italic Helvetica Light hat two letters ss w it cam gue e f can rom u . I Yo t h d. as n b ha e rt en ho a s ro n u e n t d it r fo w r s h a u n w ) d r e e m d a s n o r f e y t e t a e r b s , a b s u d t e d e e n m t i a ( n l d o b s o m a y r S e - d t w A i e t h h t t , h d e n a a s d r v e e p n t m a o f e e h m t e a k i i l . -

Adobe Type Library Online Adobe Font Folio™ 9.0 Adobe Type Basics Adobe Type Library Reference Book Adobe Type Manager® Deluxe

Adobe offers one of the largest collections of high-quality typefaces in the world, bringing you the combination of typographic excellence with the convenience of round-the-clock availability. Whether you're communicating via print, web, video, or ePaper®, Adobe Type gives you the power to create, manage and deliver your message with the richness and reliability you've come to expect from Adobe. The Adobe Type Library Online Adobe Font Folio™ 9.0 Adobe Type Basics Adobe Type Library Reference Book Adobe Type Manager® Deluxe The Adobe Type Library Online With more than 2,750 typefaces from internationally renowned foundries, such as Adobe, Agfa Monotype, ITC, and Linotype, as well as award-winning individual type designers and distinguished design studios, the Adobe Type Library offers one of the largest collections of high-quality type in the world. Choose from thousands of fonts in the PostScript® Type 1 format, offered in broad range of outstanding designs and exciting styles. And now you can also select from hundreds of fonts in the new OpenType® format, which offers improved cross-platform document portability, richer linguistic support, powerful typographic capabilities, and simplified font management. Whether you're publishing to print, web, video, or ePaper, Adobe typefaces work seamlessly with most popular software applications. Best of all, you can access any of the high-quality Adobe typefaces you need, anytime you need them, directly from the Adobe web site. You can browse, preview, purchase and immediately download any font from the online Adobe Type Library at your convenience - day or night. Simply visit http://www.adobe.com/type in North America, or at the Adobe Download Centre at http://downloadcentre.adobe.com in many other regions of the world, including Europe, Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and more to come.