John Beard and the London Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

The Return of Handel's Giove in Argo

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL 1685-1759 Giove in Argo Jupiter in Argos Opera in Three Acts Libretto by Antonio Maria Lucchini First performed at the King’s Theatre, London, 1 May 1739 hwv a14 Reconstructed with additional recitatives by John H. Roberts Arete (Giove) Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani tenor Iside Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Erasto (Osiri) Vito Priante bass Diana Theodora Baka mezzo-soprano Calisto Karina Gauvin soprano Licaone Johannes Weisser baritone IL COMPLESSO BAROCCO Alan Curtis direction 2 Ouverture 1 Largo – Allegro (3:30) 1 2 A tempo di Bourrée (1:29) ATTO PRIMO 3 Coro Care selve, date al cor (2:01) 4 Recitativo: Licaone Imbelli Dei! (0:48) 5 Aria: Licaone Affanno tiranno (3:56) 6 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (3:20) 7 Recitativo: Diana Della gran caccia, o fide (0:45) 8 Aria: Diana Non ingannarmi, cara speranza (7:18) 9 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (1:12) 10 Aria: Iside Deh! m’aiutate, o Dei (2:34) 11 Recitativo: Iside Fra il silenzio di queste ombrose selve (1:01) 12 Arioso: Iside Vieni, vieni, o de’ viventi (1:08) 13 Recitativo: Arete Iside qui, fra dolce sonno immersa? (0:23) 14 Aria: Arete Deh! v’aprite, o luci belle (3:38) 15 Recitativo: Iside, Arete Olà? Chi mi soccorre? (1:39) 16 Aria: Iside Taci, e spera (3:39) 17 Arioso: Calisto Tutta raccolta ancor (2:03) 18 Recitativo: Calisto, Erasto Abbi, pietoso Cielo (1:52) 19 Aria: Calisto Lascia la spina (2:43) 20 Recitativo: Erasto, Arete Credo che quella bella (1:23) 21 Aria: Arete Semplicetto! a donna credi? (6:11) 22 Recitativo: Erasto Che intesi mai? (0:23) 23 Aria: Erasto -

The Baritone Voice in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: a Brief Examination of Its Development and Its Use in Handel’S Messiah

THE BARITONE VOICE IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES: A BRIEF EXAMINATION OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND ITS USE IN HANDEL’S MESSIAH BY JOSHUA MARKLEY Submitted to the graduate degree program in The School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Stephens ________________________________ Dr. Michelle Hayes ________________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ________________________________ Dr. Julia Broxholm ________________________________ Mr. Mark Ferrell Date Defended: 06/08/2016 The Dissertation Committee for JOSHUA MARKLEY certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE BARITONE VOICE IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES: A BRIEF EXAMINATION OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND ITS USE IN HANDEL’S MESSIAH ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Stephens Date approved: 06/08/2016 ii Abstract Musicians who want to perform Handel’s oratorios in the twenty-first century are faced with several choices. One such choice is whether or not to use the baritone voice, and in what way is best to use him. In order to best answer that question, this study first examines the history of the baritone voice type, the historical context of Handel’s life and compositional style, and performing practices from the baroque era. It then applies that information to a case study of a representative sample of Handel’s solo oratorio literature. Using selections from Messiah this study charts the advantages and disadvantages of having a baritone sing the solo parts of Messiah rather than the voice part listed, i.e. tenor or bass, in both a modern performance and an historically-informed performance in an attempt to determine whether a baritone should sing the tenor roles or bass roles and in what context. -

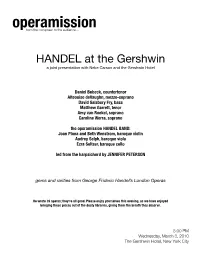

Handel 3 March Program

operamission from the composer to the audience… HANDEL at the Gershwin a joint presentation with Neke Carson and the Gershwin Hotel Daniel Bubeck, countertenor Alteouise deVaughn, mezzo-soprano David Salsbery Fry, bass Matthew Garrett, tenor Amy van Roekel, soprano Caroline Worra, soprano the operamission HANDEL BAND: Joan Plana and Beth Wenstrom, baroque violin Audrey Selph, baroque viola Ezra Seltzer, baroque cello led from the harpsichord by JENNIFER PETERSON gems and rarities from George Frideric Handel’s London Operas He wrote 39 operas; they’re all good. Please enjoy yourselves this evening, as we have enjoyed bringing these pieces out of the dusty libraries, giving them the breath they deserve. 8:00 PM Wednesday, March 3, 2010 The Gershwin Hotel, New York City program berenice - Sinfonia to open the third Act Please meet the operamission HANDEL BAND through this grand music. The fiery drama set in Alexandria in the year 80 BC in- volves a intense dynastic struggle between Sulla’s Rome and the Queen of Egypt. ariodante - “Vezzi, lusinghe, e brio” - “Orrida a gl’occhi miei” The opera opens with the Princess Ginevra (Caroline Worra) admiring herself in the mirror. All is well. She and Ariodante are in love, her father approves; this is affirmed in a brief conversation with her lady-in-waiting, Dalinda (Alteouise deVaughn), after which who should appear but the Duke of Albany, Polinesso (David Salsbery Fry). His unwelcome advances will continue to be the major source of conflict throughout the drama. Ginevra will have none of it, as she aptly displays in her first da capo aria. -

Download Booklet

CORO The Sixteen Edition CORO The Sixteen Edition Other Sixteen Edition Blest Cecilia recordings available on Coro Britten Volume 1 COR16006 Iste Confessor "A disc of Samson exceptional quality, The Sacred Music of reinforcing the George Frideric Handel Domenico Scarlatti Sixteen's reputation COR16003 as one of the finest The Sixteen “Outstanding... astonishing choirs of our day." The Symphony of Harmony and Invention stylistic and expressive range” GRAMOPHONE BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE HARRY CHRISTOPHERS The Call of The Beloved The Fairy Queen T HOMAS R ANDLE Victoria Purcell COR16007 2CD set M ARK P ADMORE "If one can ever achieve COR16005 complete emotional "A performance like L YNDA R USSELL expression through the this shows dimensions of power of music, then Purcell's genius that are all L YNNE D AWSON here it is." too rarely heard on disc" HARRY CHRISTOPHERS GRAMOPHONE C ATHERINE W YN -R OGERS Gramophone magazine said of The Sixteen’s recordings “This is what recording should be about...excellent performances and recorded sound...beautiful and moving.” M ICHAEL G EORGE Made in Great Britain J ONATHAN B EST For details of discs contact The Sixteen Productions Ltd. 00 44 1869 331544 or see www.thesixteen.com; e-mail [email protected] N The Sixteen For many years Handel’s G.F. HANDEL (1685-1759) Samson was every British SAMSON choral society’s antidote to SAMSON Messiah. However, over the n 1739 at least two Miltonic projects were urged upon Handel by a circle of wealthy supporters An Oratorio in 3 Acts by past two or three decades it including Jennens, the philosopher James Harris and the 4th Earl of Shaftesbury. -

573914 Itunes Handel

HANDEL Total Eclipse: Music for Handel’s Tenor Excerpts from Alexander’s Feast, Israel in Egypt, Saul, Messiah and Samson Aaron Sheehan, Tenor Stephen Stubbs, Conductor, Lute and Guitar Pacific MusicWorks Orchestra Alexander’s Feast, HWV 75 (excerpts) 3:30 George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) 1 (texts: Newburgh Hamilton, 1691–1761; John Dryden, 1631–1700) 2 Part II – Recitative: Give the vengeance due 1:22 Total Eclipse: Music for Handel’s Tenor Part II – Aria: The princes applaud with a furious joy 2:08 A Note from the Artistic Director Handel’s Tenor, John Beard (c. 1716–1791) Israel in Egypt, HWV 54 (excerpt) 2:04 (text: Bible – Old Testament) 3 In February 2015, my wife Maxine and I went to LA for John Beard first came to Handel’s attention at a Part III: Moses’ Song – Air: The enemy said, I will pursue 2:04 the GRAMMY ® Awards, as did Aaron Sheehan and his performance in 1732 of his oratorio Esther in a Ode for St Cecilia’s Day, HWV 76 (excerpt) 4:23 partner Adam Pearl. It’s true, Aaron and I had a recording performance to celebrate Handel’s 47th birthday. At that 4 (text: John Dryden, 1631–1700) which was nominated in the Best Opera Recording point Beard was a chorister in the Chapel Royal, just 16 Aria: Sharp violins proclaim their jealous pangs 4:23 category, but I told Maxine, that though I thought we had years old, and was given a cameo solo part of the Saul, HWV 53 (excerpts) 6:07 little chance of winning, I wanted to attend because it is Israelite Priest. -

ARIODANTE.Indd 1 2/6/19 9:32 AM

HANDEL 1819-Cover-ARIODANTE.indd 1 2/6/19 9:32 AM LYRIC OPERA OF CHICAGO Table of Contents MICHAEL COOPER/CANADIAN OPERA COMPANY OPERA MICHAEL COOPER/CANADIAN IN THIS ISSUE Ariodante – pp. 18-30 4 From the General Director 22 Artist Profiles 48 Major Contributors – Special Events and Project Support 6 From the Chairman 27 Opera Notes 49 Lyric Unlimited Contributors 8 Board of Directors 30 Director's Note 50 Commemorative Gifts 9 Women’s Board/Guild Board/Chapters’ 31 After the Curtain Falls Executive Board/Young Professionals/Ryan 51 Ryan Opera Center 32 Music Staff/Orchestra/Chorus Opera Center Board 52 Ryan Opera Center Alumni 33 Backstage Life 10 Administration/Administrative Staff/ Around the World Production and Technical Staff 34 Artistic Roster 53 Ryan Opera Center Contributors 12 Notes of the Mind 35 Patron Salute 54 Planned Giving: e Overture Society 18 Title Page 36 Production Sponsors 56 Corporate Partnerships 19 Synopsis 37 Aria Society 57 Matching Gifts, Special anks, and 21 Cast 47 Supporting Our Future – Acknowledgements Endowments at Lyric 58 Annual Individual and Foundation Support 64 Facilities and Services/eater Staff NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH NATIONAL On the cover: Findlater Castle, near Sandend, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Photo by Andrew Cioffi. CONNECTING MUSIC WITH THE MIND – pp. 12-17 2 | March 2 - 17, 2019 LYRIC OPERA OF CHICAGO From the General Director STEVE LEONARD STEVE Lyric’s record of achievement in the operas of George Frideric Handel is one of the more unlikely success stories in any American opera company. ese operas were written for theaters probably a third the size of the Lyric Opera House, and yet we’ve repeatedly demonstrated that Handel can make a terrifi c impact on our stage. -

Handel & John Beard

SCHOLARSHIP HANDEL & JOHN BEARD (Paper given to the 2005 Handel Symposium) JOHN BEARD: THE TENOR VOICE THAT INSPIRED HANDEL, ARNE AND BOYCE 1. 1732-1742 The only singer who took part in performances of every single one of Handel’s English Oratorios was the tenor John Beard. Having first heard him as a talented chorister in the Chapel Royal choir when Bernard Gates mounted a performance of “Esther”1 to celebrate his 47th birthday,2 Handel remembered his potential, and nurtured the young protégé when his treble voice turned to a useful tenor. Beard’s ‘broken’ voice must have matured remarkably quickly. 3 There is a letter of 1734 which describes him as having ‘left the Chappel at Easter’.4 This may well have been partially correct, even though his discharge papers from the choir are dated October.5 As Burrows suggests, Beard may have stayed on and sung as a tenor for the next six months “on account of his general usefulness to the choir”6. At this early stage the possibility of obtaining a permanent position in the back row of the choir may have seemed his most likely career-prospect. And yet, on November 8th, a mere ten days after being honourably dismissed from Royal service, he appeared at Covent Garden Theatre as Silvio in Handel’s “Il Pastor Fido”. It was the beginning of a relationship that would last throughout the remaining twenty-five years of Handel’s life. Henceforward Beard would always be his tenor of choice. The first oratorio that had a part specifically written for his voice was Alexander’s Feast. -

Handel, His Contemporaries and Early English Oratorio Händel, Njegovi Sodobniki in Zgodnji Angleški Oratorij

M. GARDNER • HANDEL, HIS CONTEMPORARIES ... UDK 784.5Handel Matthew Gardner Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Univerza v Heidelbergu Handel, His Contemporaries and Early English Oratorio Händel, njegovi sodobniki in zgodnji angleški oratorij Prejeto: 4. februar 2012 Received: 4th February 2012 Sprejeto: 15. marec 2012 Accepted: 15th March 2012 Ključne besede: Händel, Greene, Boyce, Apollo Keywords: Handel, Greene, Boyce, Apollo Acad- Academy, angleški oratorij emy, English Oratorio Iz v l e č e k Ab s t r a c t Pregled razvoja angleškega oratorija od prvih Surveys the development of English oratorio from javnih uprizoritev Händlovega oratorija Esther the first public performances of Handel’s Esther (1732) do 1740. Obravnava vpliv Händla na nje- (1732) until c. 1740. Handel’s influence over his gove angleške sodobnike glede na slog, obliko, English contemporaries is discussed referring to izbiro teme in alegorično vsebino, ter prikaže bolj style, formal design, subject choice and allegorical celovito podobo angleškega oratorija v 30. letih 18. content, providing a more complete than hitherto stoletja kot kdaj koli doslej. picture of the genre in the 1730s. When Handel gave the first public performance of an English oratorio with Esther in 1732, he was introducing London audiences to a new form of theatrical entertain- ment that would eventually become the staple of his London theatre seasons.1 The first ‘public’ performances of Esther took place at the Crown and Anchor Tavern at the end of February and beginning of March 1732 and were well received; several weeks later, on 2 May, it was performed in the theatre with additions taken from various earlier works including the Coronation Anthems (1727) and with a new opening scene.2 The 1 This article was originally presented as a conference paper under the title ‘Esther and Handel’s English Contemporaries’ at the American Handel Society conference in Seattle, March 2011; it appears here in a revised version. -

Ariodante Opera in Three Acts

Ariodante Opera in three acts Music by George Frideric Handel Libretto based on Antonio Salvi First performance: Covent Garden, London; Jnuary 8, 1735 ******************* Program note by Martin Pearlman Handel, Ariodante In the summer of 1734, Handel lost his position as director at the King's Theatre in London. Some of his rivals thought that he might be forced to retire, but to their surprise, he quickly signed a deal with the recently opened theater at Covent Garden and began work on another opera. The new venue, as it turned out, not only allowed him to continue his work, but -- for the several years that it was still solvent -- it offered him opportunities that he had not had before. John Rich, the impresario of the theater, was known for elaborate productions, and Handel was offered not only spectacular sets, but also dancers and even a small chorus. Until then, he had generally followed Italian operatic traditions by rarely incorporating dances and by having opera "choruses" sung only by the soloists. Ariodante premiered in January of 1735. It was Handel's first opera for Covent Garden, but it was not the great success that he hoped for. Although the eighteenth-century historian Charles Burney wrote that it "abounds with beauties and strokes of a great master," one contemporary wrote that it was "sometimes performed to an almost empty Pitt," and, despite its happy ending, Queen Caroline said that it was considered "so pathetic and lugubrious" that everyone "has been saddened by it." It was briefly revived in the following season but without the dances and with a new castrato who, not having had time to learn his arias, replaced them with Italian arias that he happened to know. -

Chapter 4 : Resumption of Work with Handel

76 CHAPTER 4 : RESUMPTION OF WORK AT THE THEATRE 1. DRURY LANE: SEPTEMBER 1741 – MAY 1743 After his break from the theatre in 1740 Beard was desperate for work. But he didn’t sing in the Oratorio season which ran from January 10th until April 8th 1741 at Lincoln’s Inn Fields theatre. It is a mystery why he didn’t go cap in hand to Handel. Perhaps he felt that he had ‘queered his pitch’ with him; or learned that Handel had made definite arrangements to manage without him. Perhaps he approached him too late. Some works (such as Deidamia) no longer required a tenor; and for others (such as L’Allegro and Acis) a certain ‘Mr Corfe’1 had been engaged. This season was a significant one for Handel as it finally marked his move away from opera to oratorio. Imeneo and Deidamia were given their final performances. Handel would perform no more operas after this. He was not even certain of his next career move. London was not a place where his music was appreciated anymore. It was with delight that he took up the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland’s invitation to visit Dublin. For Beard there was nothing for it but to eat humble pie and beg for a job at one of the main theatres. He must have been desperate to regain his position at Drury Lane. In effect he had lost it utterly, since Fleetwood had replaced him with Thomas Lowe. Lowe had inherited all his roles, from ‘Macheath’ in the main-piece Beggar’s Opera down to ‘Sir John Loverule’ in The Devil to Pay, and including the important operatic parts in Arne’s Comus and Rosamond.