Characterizations of Semele in Handel's Dramatic Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

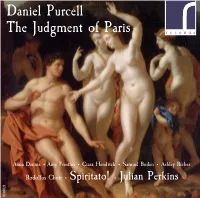

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

Download Booklet

SIGCD656_16ppBklt**.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 19/11/2020 17:06 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. 16 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm SIGCD656_16ppBklt**.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 19/11/2020 17:06 Page 2 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. rEDISCOvErEd British Clarinet Concertos Dolmetsch • Maconchy • Spain-Dunk • Wishart 1. Cantilena (Poem) for Clarinet and Orchestra, Op. 51 * Susan Spain-Dunk (1880-1962) ............[11.32] Concertino for Clarinet and String Orchestra Elizabeth Maconchy (1907-1994) 2. I. Allegro .....................................................................................................................................................................................................................[5.01] 3. II. Lento .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................[6.33] 4. III. Allegro ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. [5.32] Concerto for Clarinet, Harp and Orchestra * Rudolph Dolmetsch (1906-1942) 5. I. Allegro moderato ......................................................................................................................................................................................[10.34] -

Liturgical Drama in Bach's St. Matthew Passion

Uri Golomb Liturgical drama in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion Bach’s two surviving Passions are often cited as evidence that he was perfectly capable of producing operatic masterpieces, had he chosen to devote his creative powers to this genre. This view clashes with the notion that church music ought to be calm and measured; indeed, Bach’s contract as Cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig stipulated: In order to preserve the good order in the churches, [he would] so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion. (New Bach Reader, p. 105) One could argue, however, that Bach was never entirely faithful to this pledge, and that in the St. Matthew Passion he came close to violating it entirely. This article explores the fusion of the liturgical and the dramatic in the St. Matthew Passion, viewing the work as the combination of two dramas: the story of Christ’s final hours, and the Christian believer’s response to this story. This is not, of course, the only viable approach to this masterpiece. The St. Matthew Passion is a complex, heterogeneous work, rich in musical and expressive detail yet also displaying an impressive unity across its vast dimensions. This article does not pretend to explore all the work’s aspects; it only provides an overview of one of its distinctive features. 1. The St. Matthew Passion and the Passion genre The Passion is a musical setting of the story of Christ’s arrest, trial and crucifixion, intended as an elaboration of the Gospel reading in the Easter liturgy. -

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011 the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space; and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 22nd year in August, with “Sibelius and His World.” The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. ©2011 Bard College. All rights reserved. Cover Danae and the Shower of Gold (krater detail), ca. 430 bce. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY. Inside Back Cover ©Peter Aaron ’68/Esto The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher President Leon Botstein Honorary Patron Martti Ahtisaari, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former president of Finland Die Liebe der Danae (The Love of Danae) Music by Richard Strauss Libretto by Joseph Gregor, after a scenario by Hugo von Hofmannsthal Directed by Kevin Newbury American Symphony Orchestra Conducted by Leon Botstein, Music Director Set Design by Rafael Viñoly and Mimi Lien Choreography by Ken Roht Costume Design by Jessica Jahn Lighting Design by D. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CATALOGUE 2018 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany CEO: Jan Mojto Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

George Frideric Handel Cc 9127 George Frideric Handel

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL CC 9127 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL male lead in The Bear for Hemsley, who played it under the composer on BBC Television in George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) 1970. His book Singing and Imagination is a lucid guide to his finely-honed art. = `çåÅÉêíç=áå=_JÑä~í=ets=OVQ=léK=Q=kçK=S=ENTPSF= NNKNN Geraint Jones (1917-98). The son of a Glamorgan minister, Jones studied at the Royal 1-3 I Andante allegro 3.53 2 II Larghetto 4.31 3 III Allegro moderato 2.53 Academy of Music before being rejected for World War II service on grounds of poor health. Osian Ellis, harp. The Boyd Neel Orchestra directed by Thurston Dart Determined to ‘do his bit’, he made his debut as a harpsichordist in 1940 at one of Myra Hess’s A BBC studio broadcast, 26 February 1957 National Gallery concerts, later touring widely with his wife, the violinist Winifred Roberts. After the war he became highly influential in the ‘authentic’ baroque movement, forming his own = ^éçääç=É=a~ÑåÉ=ets=NOO=ENTNMF= QPKMR orchestra for the acclaimed performances at London’s Mermaid Theatre in 1951 of Dido and Aeneas, with Kirsten Flagstad and Thomas Hemsley. Jones’s many recordings included Dido 4 Recitative and Aria Apollo ‘La terra è liberata … Pende il ben dell’universo’ 5.18 (The earth is set free … The good of the universe) with those singers (plus Elisabeth Schwarzkopf as Belinda and Arda Mandikian as the 5 Recitative and Aria Apollo 3.54 Sorceress) as well as music by Bach, Handel and Mozart. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

The Return of Handel's Giove in Argo

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL 1685-1759 Giove in Argo Jupiter in Argos Opera in Three Acts Libretto by Antonio Maria Lucchini First performed at the King’s Theatre, London, 1 May 1739 hwv a14 Reconstructed with additional recitatives by John H. Roberts Arete (Giove) Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani tenor Iside Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Erasto (Osiri) Vito Priante bass Diana Theodora Baka mezzo-soprano Calisto Karina Gauvin soprano Licaone Johannes Weisser baritone IL COMPLESSO BAROCCO Alan Curtis direction 2 Ouverture 1 Largo – Allegro (3:30) 1 2 A tempo di Bourrée (1:29) ATTO PRIMO 3 Coro Care selve, date al cor (2:01) 4 Recitativo: Licaone Imbelli Dei! (0:48) 5 Aria: Licaone Affanno tiranno (3:56) 6 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (3:20) 7 Recitativo: Diana Della gran caccia, o fide (0:45) 8 Aria: Diana Non ingannarmi, cara speranza (7:18) 9 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (1:12) 10 Aria: Iside Deh! m’aiutate, o Dei (2:34) 11 Recitativo: Iside Fra il silenzio di queste ombrose selve (1:01) 12 Arioso: Iside Vieni, vieni, o de’ viventi (1:08) 13 Recitativo: Arete Iside qui, fra dolce sonno immersa? (0:23) 14 Aria: Arete Deh! v’aprite, o luci belle (3:38) 15 Recitativo: Iside, Arete Olà? Chi mi soccorre? (1:39) 16 Aria: Iside Taci, e spera (3:39) 17 Arioso: Calisto Tutta raccolta ancor (2:03) 18 Recitativo: Calisto, Erasto Abbi, pietoso Cielo (1:52) 19 Aria: Calisto Lascia la spina (2:43) 20 Recitativo: Erasto, Arete Credo che quella bella (1:23) 21 Aria: Arete Semplicetto! a donna credi? (6:11) 22 Recitativo: Erasto Che intesi mai? (0:23) 23 Aria: Erasto -

74Th Baldwin-Wallace College Bach Festival

The 74th Annual BALDWIN-WALLACE Bach Festival Annotated Program April 21-22, 2006 Save the date! 2007 75th B-W BACH FESTIVAL Friday, Saturday, and Sunday April 20–22, 2007 Including a combined concert with the Bethlehem Bach Choir, celebrating its 100th Festival, in Severance Hall. The Mass in B Minor will be featured. Check our Web site for details www.bw.edu/bachfest Featured Soloists presented with support from the E. Nakamichi Foundation and The Adrianne and Robert Andrews Bach Festival Fund in honor of Amelia & Elias Fadil BALDWIN-WALLACE COLLEGE SEVENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL BACH FESTIVAL THE OLDEST COLLEGIATE BACH FESTIVAL IN THE NATION ANNOTATED PROGRAM APRIL 21–22, 2006 DEDICATION THE SEVENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL BACH FESTIVAL IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED TO RUTH PICKERING (1918–2005), WHO SO LOVED MUSIC, THE BALDWIN-WALLACE COLLEGE BACH FESTIVAL AND CONSERVATORY CONCERTS, THAT SHE AND HER LATE HUSBAND, DON, HAD THEIR NAMES ENGRAVED ON BRASS PLAQUES AND AFFIXED TO THEIR FAVORITE SEATS, DD 24 AND DD 25, IN THE BALCONY OF GAMBLE HALL, KULAS MUSICAL ARTS BUILDING. SHE WILL BE REMEMBERED WITH MUCH LOVE BY MANY FROM THIS COMMUNITY, IN WHICH SHE WAS SO ACTIVE. Third Sunday Chapel Series at Baldwin-Wallace College Lindsay-Crossman A concert series under the direction of Warren Scharf, Margaret Scharf, and Nicole Keller 2006-2007 Concert Schedule Third Sundays at 7:45 p.m. Our Sixth Season October 15, 2006 March 18, 2007 November 19, 2006 April 15, 2007 December 17, 2006 The public is warmly invited to attend these free concerts. The Chapel is handicapped accessible. -

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30Pm, Hall

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30pm, Hall The English Concert Harry Bicket conductor/harpsichord Iestyn Davies Rinaldo Jane Archibald Armida Sasha Cooke Goffredo Joélle Harvey Almirena/Siren Luca Pisaroni Argante Jakub Józef Orli ´nski Eustazio Owen Willetts Araldo/Donna/Mago Richard Haughton Richard There will be two intervals of 20 minutes following Act 1 and Act 2 Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 We appreciate that it’s not always possible to prevent coughing during a performance. But, for the sake of other audience members and the artists, if you feel the need to cough or sneeze, please stifle it with a handkerchief. Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel 020 3603 7930) Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight we welcome back Harry Bicket as delighted by the extravagant magical and The English Concert for Rinaldo, the effects as by Handel’s endlessly inventive latest instalment in their Handel opera music. And no wonder – for Rinaldo brings series. Last season we were treated to a together love, vengeance, forgiveness, spine-tingling performance of Ariodante, battle scenes and a splendid sorceress with a stellar cast led by Alice Coote. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No.