The Tenor Roles in the Oratorios of George

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011 the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space; and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 22nd year in August, with “Sibelius and His World.” The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. ©2011 Bard College. All rights reserved. Cover Danae and the Shower of Gold (krater detail), ca. 430 bce. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY. Inside Back Cover ©Peter Aaron ’68/Esto The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher President Leon Botstein Honorary Patron Martti Ahtisaari, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former president of Finland Die Liebe der Danae (The Love of Danae) Music by Richard Strauss Libretto by Joseph Gregor, after a scenario by Hugo von Hofmannsthal Directed by Kevin Newbury American Symphony Orchestra Conducted by Leon Botstein, Music Director Set Design by Rafael Viñoly and Mimi Lien Choreography by Ken Roht Costume Design by Jessica Jahn Lighting Design by D. -

The Baroque. 3.3: Vocal Music: the Da Capo Aria and Other Types of Arias

UNIT 3: THE BAROQUE. 3.3: VOCAL MUSIC: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS EXPLANATION 3.3: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS. THE ARIA The aria in the operas is the part sung by the soloist. It is opposed to the recitative, which uses the recitative style. In the arias the composer shows and exploits the dramatic and emotional situations, it becomes the equivalent of a soliloquy (one person speach) in the spoken plays. In the arias, the interpreters showed their technique, they showed off, even in excess, which provoked a lot of criticism from poets and musicians. They were often sung by castrati: soprano men undergoing a surgical operation so as not to change their voice when they grew up. One of them, the most famous, Farinelli, acquired international fame for his great technique and vocal expression. He lived twenty-five years in Spain. THE DA CAPO ARIA The Da Capo aria is a vocal work in three parts or sections (tripartite form). It began to be used in the Baroque in operas, oratorios and cantatas. The form is A - B - A, the last part being a repetition of the first. 1. The first section is a complete musical entity, that is to say, it could be sung alone and musically it would have complete meaning since it ends in the tonic. The tonic is the first grade or note of a scale. 2. The second section contrasts with the first section in tonality, texture, mood and sometimes in tempo (speed). 3. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for Cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009

CORO CORO HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009 “Overall, this disc ranks as The Sixteen’s most exciting achievement in its impressive Handel discography.” HANDEL gramophone Choruses HANDEL: Dixit Dominus cor16076 STEFFANI: Stabat Mater The Sixteen adds to its stunning Handel collection with a new recording of Dixit Dominus set alongside a little-known treasure – Agostino Steffani’s Stabat Mater. THE HANDEL COLLECTION cor16080 Eight of The Sixteen’s celebrated Handel recordings in one stylish boxed set. The Sixteen To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit HARRY CHRISTOPHERS www.thesixteen.com cor16180 He is quite simply the master of chorus and on this compilation there is much rejoicing. Right from the outset, a chorus of Philistines revel in Awake the trumpet’s lofty sound to celebrate Dagon’s festival in Samson; the Israelites triumph in their victory over Goliath with great pageantry in How excellent Thy name from Saul and we can all feel the exuberance of I will sing unto the Lord from Israel in Egypt. There are, of course, two Handel oratorios where the choruses dominate – Messiah and Israel in Egypt – and we have given you a taster of pure majesty in the Amen chorus from Messiah as well as the Photograph: Marco Borggreve Marco Photograph: dramatic ferocity of He smote all the first-born of Egypt from Israel in Egypt. Handel is all about drama; even though he forsook opera for oratorio, his innate sense of the theatrical did not leave him. Just listen to the poignancy of the opening of Act 2 from Acis and Galatea where the chorus pronounce the gloomy prospect of the lovers and the impending appearance of the monster Polyphemus; and the torment which the Israelites create in O God, behold our sore distress when Jephtha commands them to “invoke the holy name of Israel’s God”– it’s surely one of his greatest fugal choruses. -

CHORAL PROBLEMS in HANDEL's MESSIAH THESIS Presented to The

*141 CHORAL PROBLEMS IN HANDEL'S MESSIAH THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By John J. Williams, B. M. Ed. Denton, Texas May, 1968 PREFACE Music of the Baroque era can be best perceived through a detailed study of the elements with which it is constructed. Through the analysis of melodic characteristics, rhythmic characteristics, harmonic characteristics, textural charac- teristics, and formal characteristics, many choral problems related directly to performance practices in the Baroque era may be solved. It certainly cannot be denied that there is a wealth of information written about Handel's Messiah and that readers glancing at this subject might ask, "What is there new to say about Messiah?" or possibly, "I've conducted Messiah so many times that there is absolutely nothing I don't know about it." Familiarity with the work is not sufficient to produce a performance, for when it is executed in this fashion, it becomes merely a convention rather than a carefully pre- pared piece of music. Although the oratorio has retained its popularity for over a hundred years, it is rarely heard as Handel himself performed it. Several editions of the score exist, with changes made by the composer to suit individual soloists or performance conditions. iii The edition chosen for analysis in this study is the one which Handel directed at the Foundling Hospital in London on May 15, 1754. It is version number four of the vocal score published in 1959 by Novello and Company, Limited, London, as edited by Watkins Shaw, based on sets of parts belonging to the Thomas Coram Foundation (The Foundling Hospital). -

12-04-2018 Traviata Eve.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI la traviata conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, production Michael Mayer based on the play La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils set designer Christine Jones Tuesday, December 4, 2018 costume designer 8:00–11:00 PM Susan Hilferty lighting designer New Production Premiere Kevin Adams choreographer Lorin Latarro DEBUT The production of La Traviata was made possible by a generous gift from The Paiko Foundation Major additional funding for this production was received from Mercedes T. Bass, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, and Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 1,012th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S la traviata conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance violet ta valéry annina Diana Damrau Maria Zifchak flor a bervoix giuseppe Kirstin Chávez Marco Antonio Jordão the marquis d’obigny giorgio germont Jeongcheol Cha Quinn Kelsey baron douphol a messenger Dwayne Croft* Ross Benoliel dr. grenvil Kevin Short germont’s daughter Selin Sahbazoglu gastone solo dancers Scott Scully Garen Scribner This performance Martha Nichols is being broadcast live on Metropolitan alfredo germont Opera Radio on Juan Diego Flórez SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Tuesday, December 4, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Diana Damrau Chorus Master Donald Palumbo as Violetta and Musical Preparation John Keenan, Yelena Kurdina, Juan Diego Flórez Liora Maurer, and Jonathan -

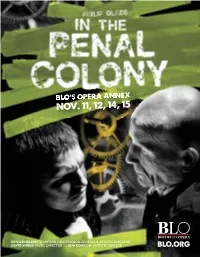

2015 in the Penal Colony Program

ESTHER NELSON, STANFORD CALDERWOOD GENERAL & ARTISTIC DIRECTOR DAVID ANGUS, MUSIC DIRECTOR | JOHN CONKLIN, ARTISTIC ADVISOR Rodolfo (Jesus Garcia) and Mimi (Kelly Kaduce) in Boston Lyric Opera’s 2015 production of La Bohème. This holiday season, share your love of opera with the ones you love. BLO off ers packages and gift certifi cates CHARLES ERICKSON T. to make your holiday shopping simple! T. CHARLES ERICKSON T. WELCOME TO THE SEVENTH IN OUR OPERA ANNEX SERIES, which is increasingly attracting national and international attention. Installing opera in non-conventional spaces has sparked a curiosity in the art. The challenges of these spaces are many and due to opera’s inherent demands: natural acoustics (since we do not amplify), adequate performance and production space, audience comfort and social space, location accessibility, parking, safety, and especially important in New England, adequate heat. Our In the Penal Colony comes amid questions and debate on the performance spaces and theatrical environment in Boston. For us, the questions include … why is Boston the only one of the top ten U.S. cities without a home suitable for opera? What are sustainable models to support new performance venues and/or preserve historic theaters? As you may have heard, BLO decided not to renew its agreement with the JesusJJesus GarciaGGarcia as RRoRodolfodldolffo Shubert Theatre after this Season. The reasons are many and complex, but suffi ce in La Bohème it to say that we made an important business and artistic decision. BLO is dedicated to spending signifi cantly more of our budget on direct artistic and production expenses and providing our patrons with a new level of service and comfort. -

A Critical Analysis of the Libretto in Handel's Messiah

Augustana College Augustana Digital Commons 2020 Festschrift: Georg Frideric Handel's "Messiah" Festschriften Fall 12-9-2020 Lost in Translation: A Critical Analysis of the Libretto in Handel's Messiah Jordan Lehto Augustana College, Rock Island Illinois Aaron Escamilla Augustana College, Rock Island Illinois Eden H. Nimietz Augustana College, Rock Island Illinois Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/muscfest2020 Part of the Composition Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Yiddish Language and Literature Commons Augustana Digital Commons Citation Lehto, Jordan; Escamilla, Aaron; and Nimietz, Eden H.. "Lost in Translation: A Critical Analysis of the Libretto in Handel's Messiah" (2020). 2020 Festschrift: Georg Frideric Handel's "Messiah". https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/muscfest2020/2 This Student Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Festschriften at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2020 Festschrift: Georg Frideric Handel's "Messiah" by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lost in Translation: A Critical Analysis of the Libretto in Handel’s Messiah Aaron Escamilla Jordan Lehto Eden Nimietz Augustana College MUSC-311--Styles and Literature of Music I November 9, 2020 Escamilla, Lehto, Nimietz 2 Abstract Handel’s Messiah is renowned for its lush sound and richly developed message regarding the rejoicing of Christians and the celebration of religion through their faith in a divine savior. Not only is the full oratorio performed by countless ensembles every year, but many scholars have spent months, and even years, poring over its libretto. -

ELIJAH, Op. 70 (1846) Libretto: Julius Schubring English Translation

ELIJAH, Op. 70 (1846) Libretto: Julius Schubring Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847) English Translation: William Bartholomew PART ONE The Biblical tale of Elijah dates from c. 800 BCE. "In fact I imagined Elijah as a real prophet The core narrative is found in the Book of Kings through and through, of the kind we could (I and II), with minor references elsewhere in really do with today: Strong, zealous and, yes, the Hebrew Bible. The Haggadah supplements even bad-tempered, angry and brooding — in the scriptural account with a number of colorful contrast to the riff-raff, whether of the court or legends about the prophet’s life and works. the people, and indeed in contrast to almost the After Moses, Abraham and David, Elijah is the whole world — and yet borne aloft as if on Old Testament character mentioned most in the angels' wings." – Felix Mendelssohn, 1838 (letter New Testament. The Qu’uran also numbers to Julius Schubring, Elijah’s librettist) Elijah (Ilyas) among the major prophets of Islam. Elijah’s name is commonly translated to mean “Yahweh is my God.” PROLOGUE: Elijah’s Curse Introduction: Recitative — Elijah Elijah materializes before Ahab, king of the Four dark-hued chords spring out of nowhere, As God the Lord of Israel liveth, before Israelites, to deliver a bitter curse: Three years of grippingly setting the stage for confrontation.1 whom I stand: There shall not be dew drought as punishment for the apostasy of Ahab With the opening sentence, Mendelssohn nor rain these years, but according to and his court. The prophet’s appearance is a introduces two major musical motives that will my word. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Handel Arias

ALICE COOTE THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET HANDEL ARIAS HERCULES·ARIODANTE·ALCINA RADAMISTO·GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL A portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685–1749) 2 CONTENTS TRACK LISTING page 4 ENGLISH page 5 Sung texts and translation page 10 FRANÇAIS page 16 DEUTSCH Seite 20 3 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) Radamisto HWV12a (1720) 1 Quando mai, spietata sorte Act 2 Scene 1 .................. [3'08] Alcina HWV34 (1735) 2 Mi lusinga il dolce affetto Act 2 Scene 3 .................... [7'45] 3 Verdi prati Act 2 Scene 12 ................................. [4'50] 4 Stà nell’Ircana Act 3 Scene 3 .............................. [6'00] Hercules HWV60 (1745) 5 There in myrtle shades reclined Act 1 Scene 2 ............. [3'55] 6 Cease, ruler of the day, to rise Act 2 Scene 6 ............... [5'35] 7 Where shall I fly? Act 3 Scene 3 ............................ [6'45] Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17 (1724) 8 Cara speme, questo core Act 1 Scene 8 .................... [5'55] Ariodante HWV33 (1735) 9 Con l’ali di costanza Act 1 Scene 8 ......................... [5'42] bl Scherza infida! Act 2 Scene 3 ............................. [11'41] bm Dopo notte Act 3 Scene 9 .................................. [7'15] ALICE COOTE mezzo-soprano THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET conductor 4 Radamisto Handel diplomatically dedicated to King George) is an ‘Since the introduction of Italian operas here our men are adaptation, probably by the Royal Academy’s cellist/house grown insensibly more and more effeminate, and whereas poet Nicola Francesco Haym, of Domenico Lalli’s L’amor they used to go from a good comedy warmed by the fire of tirannico, o Zenobia, based in turn on the play L’amour love and a good tragedy fired with the spirit of glory, they sit tyrannique by Georges de Scudéry.