Chapter 4 : Resumption of Work with Handel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Shearer West Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON (VOL. I) Shearer West A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1986 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2982 This item is protected by original copyright THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON Ph.D. Thesis St. Andrews University Shearer West VOLUME 1 TEXT In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the I work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. ABSTRACT A theatrical portrait is an image of an actor or actors in character. This genre was widespread in eighteenth century London and was practised by a large number of painters and engravers of all levels of ability. The sources of the genre lay in a number of diverse styles of art, including the court portraits of Lely and Kneller and the fetes galantes of Watteau and Mercier. Three types of media for theatrical portraits were particularly prevalent in London, between ca745 and 1800 : painting, print and book illustration. -

Romeo Revived .Pdf

McGirr, E. (2017). "What's in a Name?": Romeo and Juliet and the Cibber Brand. Shakespeare. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450918.2017.1406983 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1080/17450918.2017.1406983 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Taylor and Francis at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17450918.2017.1406983. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Elaine M. McGirr Reader in Theatre & Performance Histories University of Bristol “What’s in a name?”: Romeo and Juliet and the Cibber brand Abstract: The 1744 and 1748/50 performances of Romeo and Juliet by Theophilus Cibber, Jenny Cibber and Susannah Cibber explain the significance of the play’s return to the repertory, uncover the history of rival interpretations of Juliet’s character, and make sense of the careers and reputations of the theatrical Cibbers. The “Cibberian” airs of all three Cibbers were markedly different, as were their interpretations of Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers. Keywords: Shakespearean adaptation, performance history, celebrity, authorial reputation, repertory In Romeo and Juliet, Juliet apostrophizes Romeo to deny thy father and refuse thy name, assuring her (supposedly) absent lover that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

The Return of Handel's Giove in Argo

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL 1685-1759 Giove in Argo Jupiter in Argos Opera in Three Acts Libretto by Antonio Maria Lucchini First performed at the King’s Theatre, London, 1 May 1739 hwv a14 Reconstructed with additional recitatives by John H. Roberts Arete (Giove) Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani tenor Iside Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Erasto (Osiri) Vito Priante bass Diana Theodora Baka mezzo-soprano Calisto Karina Gauvin soprano Licaone Johannes Weisser baritone IL COMPLESSO BAROCCO Alan Curtis direction 2 Ouverture 1 Largo – Allegro (3:30) 1 2 A tempo di Bourrée (1:29) ATTO PRIMO 3 Coro Care selve, date al cor (2:01) 4 Recitativo: Licaone Imbelli Dei! (0:48) 5 Aria: Licaone Affanno tiranno (3:56) 6 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (3:20) 7 Recitativo: Diana Della gran caccia, o fide (0:45) 8 Aria: Diana Non ingannarmi, cara speranza (7:18) 9 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (1:12) 10 Aria: Iside Deh! m’aiutate, o Dei (2:34) 11 Recitativo: Iside Fra il silenzio di queste ombrose selve (1:01) 12 Arioso: Iside Vieni, vieni, o de’ viventi (1:08) 13 Recitativo: Arete Iside qui, fra dolce sonno immersa? (0:23) 14 Aria: Arete Deh! v’aprite, o luci belle (3:38) 15 Recitativo: Iside, Arete Olà? Chi mi soccorre? (1:39) 16 Aria: Iside Taci, e spera (3:39) 17 Arioso: Calisto Tutta raccolta ancor (2:03) 18 Recitativo: Calisto, Erasto Abbi, pietoso Cielo (1:52) 19 Aria: Calisto Lascia la spina (2:43) 20 Recitativo: Erasto, Arete Credo che quella bella (1:23) 21 Aria: Arete Semplicetto! a donna credi? (6:11) 22 Recitativo: Erasto Che intesi mai? (0:23) 23 Aria: Erasto -

The Baritone Voice in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: a Brief Examination of Its Development and Its Use in Handel’S Messiah

THE BARITONE VOICE IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES: A BRIEF EXAMINATION OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND ITS USE IN HANDEL’S MESSIAH BY JOSHUA MARKLEY Submitted to the graduate degree program in The School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Stephens ________________________________ Dr. Michelle Hayes ________________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ________________________________ Dr. Julia Broxholm ________________________________ Mr. Mark Ferrell Date Defended: 06/08/2016 The Dissertation Committee for JOSHUA MARKLEY certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE BARITONE VOICE IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES: A BRIEF EXAMINATION OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND ITS USE IN HANDEL’S MESSIAH ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Stephens Date approved: 06/08/2016 ii Abstract Musicians who want to perform Handel’s oratorios in the twenty-first century are faced with several choices. One such choice is whether or not to use the baritone voice, and in what way is best to use him. In order to best answer that question, this study first examines the history of the baritone voice type, the historical context of Handel’s life and compositional style, and performing practices from the baroque era. It then applies that information to a case study of a representative sample of Handel’s solo oratorio literature. Using selections from Messiah this study charts the advantages and disadvantages of having a baritone sing the solo parts of Messiah rather than the voice part listed, i.e. tenor or bass, in both a modern performance and an historically-informed performance in an attempt to determine whether a baritone should sing the tenor roles or bass roles and in what context. -

~Lagfblll COMPANIES INC

May 2000 Brooklyn Academy of Music 2000 Spring Season BAMcinematek Brooklyn Philharmonic 651 ARTS Saint Clair Cemin, L'lntuition de L'lnstant, 1995 BAM 2000 Spring Season is sponsored by PHiliP MORR I S ~lAGfBlll COMPANIES INC. Contents • May 2000 Lust in the Woods 10 The Royal Shakespeare Company presents Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream at BAM in a saucy production by Michael Boyd. By Ian Shuttleworth Schiller's Shocker 22 Friedrich Schiller's riveting Don Carlos , to be performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company at BAM, still has the power to ruffle feathers. By Steven R. Cerf Program 17 Upcoming Events 43 BAMd i rectory 52 Photo by Jonathan Doc kar-Drysdale I3A 1\/1 CO\/Ar Arti,t Saint Clair Cemin Saint Clair Cemin was born in Cruz Alta , Brazil , in 1951. He studied at the Ecole Nationale L'lntuition de L'lnstant Superieure des Beaux Arts in Paris, France. He lives in New York City. 1995 Painted wood Cemin's sculpture has been exhibited worldwide, including at the Hirshhorn Museum and 97" x 91 ' x 36' Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Museo de Arte Contemporary, Monterey, Mexico; California Center for the Arts Museum , Escondido, CA; Centro Cultural For BAMart information Light, Rio de Janiero, Brazil; Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL; The Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Stadische Kunsthalle, DUsseldorf, Germany; The Fredrik Roos contact Deborah Bowie at Museum, Malmo, Sweden; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Whitney Museum 718.636.4111 ext. 380 of American Art Biennial, New York, NY; Centro Atlantico de Arte Moderno, Las Palmas, Grand Canary Island; Documenta IX, Kassel, Germany; 22nd Biennial International, Funda,ao de Sao Paolo; Galleria Communale d'Arte Moderna, Bologna , Italy; Fogg Art Museum , Cambridge, MA; and the Kunsthalle, Basel, Switzerland. -

Catherine Harbor

The Birth of the Music Business: Public Commercial Concerts In London 1660–1750 Catherine Harbor Volume 2 369 Appendix A. The Register of Music in London Newspapers 1660–1750 Database A.1 Database Design and Construction Initial database design decisions were dictated by the over-riding concern that the Register of Music in London Newspapers 1660–1750 should be a source-oriented rather than a model-oriented database, with the integrity of the source being preserved as far as possible (Denley, 1994: 33-43; Harvey and Press, 1996). The aim of the project was to store a large volume of data that had no obvious structure and to provide a comprehensive index to it that would serve both as a finding aid and as a database in its own right (Hartland and Harvey, 1989: 47-50). The result was what Harvey and Press (1996: 10) term an ‘electronic edition’ of the texts in the newspapers, together with an index or coding scheme that provided an easy way of retrieving the desired information. The stored data was divided into a text base with its physical and locational descriptors, and the index database. The design and specification of the database tables was undertaken by Charles Harvey and Philip Hartland using techniques of entity-relationship modelling and relational data analysis. These techniques are discussed in numerous texts on databases and database design and have been applied to purely historical data (Hartland and Harvey, 1989; Harvey and Press, 1996: 103-130). The Oracle relational database management system was used to create the tables, enter, store and manipulate the data. -

Handel 3 March Program

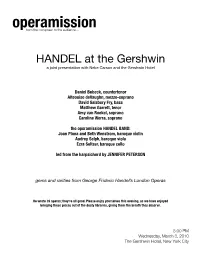

operamission from the composer to the audience… HANDEL at the Gershwin a joint presentation with Neke Carson and the Gershwin Hotel Daniel Bubeck, countertenor Alteouise deVaughn, mezzo-soprano David Salsbery Fry, bass Matthew Garrett, tenor Amy van Roekel, soprano Caroline Worra, soprano the operamission HANDEL BAND: Joan Plana and Beth Wenstrom, baroque violin Audrey Selph, baroque viola Ezra Seltzer, baroque cello led from the harpsichord by JENNIFER PETERSON gems and rarities from George Frideric Handel’s London Operas He wrote 39 operas; they’re all good. Please enjoy yourselves this evening, as we have enjoyed bringing these pieces out of the dusty libraries, giving them the breath they deserve. 8:00 PM Wednesday, March 3, 2010 The Gershwin Hotel, New York City program berenice - Sinfonia to open the third Act Please meet the operamission HANDEL BAND through this grand music. The fiery drama set in Alexandria in the year 80 BC in- volves a intense dynastic struggle between Sulla’s Rome and the Queen of Egypt. ariodante - “Vezzi, lusinghe, e brio” - “Orrida a gl’occhi miei” The opera opens with the Princess Ginevra (Caroline Worra) admiring herself in the mirror. All is well. She and Ariodante are in love, her father approves; this is affirmed in a brief conversation with her lady-in-waiting, Dalinda (Alteouise deVaughn), after which who should appear but the Duke of Albany, Polinesso (David Salsbery Fry). His unwelcome advances will continue to be the major source of conflict throughout the drama. Ginevra will have none of it, as she aptly displays in her first da capo aria. -

Download Booklet

CORO The Sixteen Edition CORO The Sixteen Edition Other Sixteen Edition Blest Cecilia recordings available on Coro Britten Volume 1 COR16006 Iste Confessor "A disc of Samson exceptional quality, The Sacred Music of reinforcing the George Frideric Handel Domenico Scarlatti Sixteen's reputation COR16003 as one of the finest The Sixteen “Outstanding... astonishing choirs of our day." The Symphony of Harmony and Invention stylistic and expressive range” GRAMOPHONE BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE HARRY CHRISTOPHERS The Call of The Beloved The Fairy Queen T HOMAS R ANDLE Victoria Purcell COR16007 2CD set M ARK P ADMORE "If one can ever achieve COR16005 complete emotional "A performance like L YNDA R USSELL expression through the this shows dimensions of power of music, then Purcell's genius that are all L YNNE D AWSON here it is." too rarely heard on disc" HARRY CHRISTOPHERS GRAMOPHONE C ATHERINE W YN -R OGERS Gramophone magazine said of The Sixteen’s recordings “This is what recording should be about...excellent performances and recorded sound...beautiful and moving.” M ICHAEL G EORGE Made in Great Britain J ONATHAN B EST For details of discs contact The Sixteen Productions Ltd. 00 44 1869 331544 or see www.thesixteen.com; e-mail [email protected] N The Sixteen For many years Handel’s G.F. HANDEL (1685-1759) Samson was every British SAMSON choral society’s antidote to SAMSON Messiah. However, over the n 1739 at least two Miltonic projects were urged upon Handel by a circle of wealthy supporters An Oratorio in 3 Acts by past two or three decades it including Jennens, the philosopher James Harris and the 4th Earl of Shaftesbury. -

Bibliographic Information for Fifty-Three Unlocated Eighteenth-Century Items in Arnott and Robinson's English Theatrical

Bibliographic Information for Fifty-three Unlocated Eighteenth-Century Items in Arnott and Robinson’s English Theatrical Literature, 1559-1900 By David Wallace Spielman In 1953, members of the Society for Theatre Research (STR) began the daunting task of revising Robert W. Lowe’s A Bibliographical Account of English Theatrical Literature (1888). In the first six years of the project, several editors came and went. As George Speaight says in his introduction, “the work proved too much for our part-time labours.”1 James Fullarton Arnott and John William Robinson were brought on board in 1959 to bring the project to completion. The resulting volume appeared in print in 1970 as English Theatrical Literature, 1559-1900: A Bibliography (hereafter A&R), one of the great achievements of the Society. A&R incorporates and substantially expands Lowe’s bibliography and has been a basic reference source for theatre historians for almost forty years. Its utility prompted John Cavanagh to continue the project up through 1985 in his British Theatre: A Bibliography, 1901 to 1985.2 Lowe personally examined all the items that he could, and Arnott and Robinson followed Lowe’s precedent in their revision and expansion. As they admit in their preface, however, the editors were not able to see everything listed in the bibliography (xii). They included some items based solely on information received from sources they deemed reliable. The amount of information provided for these items varies widely, and those with no library location supplied have long been a source of frustration to scholars. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) has made full-text facsimile copies of a substantial number of these “unseen” items readily available. -

Ballad Opera in England: Its Songs, Contributors, and Influence

BALLAD OPERA IN ENGLAND: ITS SONGS, CONTRIBUTORS, AND INFLUENCE Julie Bumpus A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 7, 2010 Committee: Vincent Corrigan, Advisor Mary Natvig ii ABSTRACT Vincent Corrigan, Advisor The ballad opera was a popular genre of stage entertainment in England that flourished roughly from 1728 (beginning with John Gay's The Beggar's Opera) to 1760. Gay's original intention for the genre was to satirize not only the upper crust of British society, but also to mock the “excesses” of Italian opera, which had slowly been infiltrating the concert life of Britain. The Beggar's Opera and its successors were to be the answer to foreign opera on British soil: a truly nationalistic genre that essentially was a play (building on a long-standing tradition of English drama) with popular music interspersed throughout. My thesis explores the ways in which ballad operas were constructed, what meanings the songs may have held for playwrights and audiences, and what influence the genre had in England and abroad. The thesis begins with a general survey of the origins of ballad opera, covering theater music during the Commonwealth, Restoration theatre, the influence of Italian Opera in England, and The Beggar’s Opera. Next is a section on the playwrights and composers of ballad opera. The playwrights discussed are John Gay, Henry Fielding, and Colley Cibber. Purcell and Handel are used as examples of composers of source material and Mr. Seedo and Pepusch as composers and arrangers of ballad opera music.