Political Parties and Interest Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions

Undergraduate Journal of Psychology 22 Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions Ida Hepsø, Scarlet Hernandez, Shir Offsey, & Katherine White Kennesaw State University Abstract The United States has exhibited two potentially connected trends – increasing individualism and increasing interest in libertarian ideology. Previous research on libertarian ideology found higher levels of individualism among libertarians, and cross-cultural research has tied greater individualism to making dispositional attributions and lower altruistic tendencies. Given this, we expected to observe positive correlations between the following variables in the present research: individualism and endorsement of libertarianism, individualism and dispositional attributions, and endorsement of libertarianism and dispositional attributions. We also expected to observe negative correlations between libertarianism and altruism, dispositional attributions and altruism, and individualism and altruism. Survey results from 252 participants confirmed a positive correlation between individualism and libertarianism, a marginally significant positive correlation between libertarianism and dispositional attributions, and a negative correlation between individualism and altruism. These results confirm the connection between libertarianism and individualism observed in previous research and present several intriguing questions for future research on libertarian ideology. Key Words: Libertarianism, individualism, altruism, attributions individualistic, made apparent -

Direct E-Democracy and Political Party Websites: in the United States and Sweden

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-1-2015 Direct E-Democracy and Political Party Websites: In the United States and Sweden Kirk M. Winans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Winans, Kirk M., "Direct E-Democracy and Political Party Websites: In the United States and Sweden" (2015). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: E-DEMOCRACY AND POLITICAL PARTY WEBSITES Direct E-Democracy and Political Party Websites: In the United States and Sweden by Kirk M. Winans Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Science, Technology and Public Policy Department of Public Policy College of Liberal Arts Rochester Institute of Technology May 1, 2015 E-DEMOCRACY AND POLITICAL PARTY WEBSITES Direct E-Democracy and Political Party Websites: In the United States and Sweden A thesis submitted to The Public Policy Department at Rochester Institute of Technology By Kirk M. Winans Under the faculty guidance of Franz Foltz, Ph.D. Submitted by: Kirk M. Winans Signature Date Accepted by: Dr. Franz Foltz Thesis Advisor, Graduate Coordinator Signature Date Associate Professor, Dept. of STS/Public Policy Rochester Institute of Technology Dr. Rudy Pugliese Committee Member Signature Date Professor, School of Communication Rochester Institute of Technology Dr. Ryan Garcia Committee Member Signature Date Assistant Professor, Dept. -

Freedom of Association with Regard to Political

Freedom of Association with regard to Political Parties and Civil Society in the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf: A literature review By Mona Marshy, PhD [email protected] (613) 236-1571 For International Development Research Centre (IDRC) 250 Albert Street Ottawa, ON K1G 3H9 April 2005 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction.....................................................................................................................................2 II. Freedom of association – A literature review............................................................................3 Democratization ..............................................................................................................................3 Definition and legal framework of the right to freedom of association:.................................5 What is the state of the right to freedom of association in the Arab world?..........................7 Assessing the efficacy of civil societies.........................................................................................9 Links between civil society, political parties, and democratization n.....................................16 Political parties in the Middle East and North Africa..............................................................18 Political participation in Gulf states............................................................................................21 Islamic movements and democratization ..................................................................................22 -

Brazil Ahead of the 2018 Elections

BRIEFING Brazil ahead of the 2018 elections SUMMARY On 7 October 2018, about 147 million Brazilians will go to the polls to choose a new president, new governors and new members of the bicameral National Congress and state legislatures. If, as expected, none of the presidential candidates gains over 50 % of votes, a run-off between the two best-performing presidential candidates is scheduled to take place on 28 October 2018. Brazil's severe and protracted political, economic, social and public-security crisis has created a complex and polarised political climate that makes the election outcome highly unpredictable. Pollsters show that voters have lost faith in a discredited political elite and that only anti- establishment outsiders not embroiled in large-scale corruption scandals and entrenched clientelism would truly match voters' preferences. However, there is a huge gap between voters' strong demand for a radical political renewal based on new faces, and the dramatic shortage of political newcomers among the candidates. Voters' disillusionment with conventional politics and political institutions has fuelled nostalgic preferences and is likely to prompt part of the electorate to shift away from centrist candidates associated with policy continuity to candidates at the opposite sides of the party spectrum. Many less well-off voters would have welcomed a return to office of former left-wing President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010), who due to a then booming economy, could run social programmes that lifted millions out of extreme poverty and who, barred by Brazil's judiciary from running in 2018, has tried to transfer his high popularity to his much less-known replacement. -

Political Parties and Welfare Associations

Department of Sociology Umeå University Political parties and welfare associations by Ingrid Grosse Doctoral theses at the Department of Sociology Umeå University No 50 2007 Department of Sociology Umeå University Thesis 2007 Printed by Print & Media December 2007 Cover design: Gabriella Dekombis © Ingrid Grosse ISSN 1104-2508 ISBN 978-91-7264-478-6 Grosse, Ingrid. Political parties and welfare associations. Doctoral Dissertation in Sociology at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Umeå University, 2007. ISBN 978-91-7264-478-6 ISSN 1104-2508 ABSTRACT Scandinavian countries are usually assumed to be less disposed than other countries to involve associations as welfare producers. They are assumed to be so disinclined due to their strong statutory welfare involvement, which “crowds-out” associational welfare production; their ethnic, cultural and religious homogeneity, which leads to a lack of minority interests in associational welfare production; and to their strong working-class organisations, which are supposed to prefer statutory welfare solutions. These assumptions are questioned here, because they cannot account for salient associational welfare production in the welfare areas of housing and child-care in two Scandinavian countries, Sweden and Norway. In order to approach an explanation for the phenomena of associational welfare production in Sweden and Norway, some refinements of current theories are suggested. First, it is argued that welfare associations usually depend on statutory support in order to produce welfare on a salient level. Second, it is supposed that any form of particularistic interest in welfare production, not only ethnic, cultural or religious minority interests, can lead to associational welfare. With respect to these assumptions, this thesis supposes that political parties are organisations that, on one hand, influence statutory decisions regarding associational welfare production, and, on the other hand, pursue particularistic interests in associational welfare production. -

Third Party Election Campaigning Getting the Balance Right

Third Party Campaigning Review Third Party Election Campaigning – Getting the Balance Right Review of the operation of the third party campaigning rules at the 2015 General Election The Lord Hodgson of Astley Abbotts CBE March 2016 Third Party Election Campaigning – Getting the Balance Right Review of the operation of the third party campaigning rules at the 2015 General Election The Lord Hodgson of Astley Abbotts CBE Presented to Parliament by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster by Command of Her Majesty March 2016 Cm 9205 © Crown copyright 2016 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] Print ISBN 9781474127950 Web ISBN 9781474127967 ID SGD0011093 03/16 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Foreword 1 Foreword I was appointed as the Reviewer of Part 2 specific topics was sent to interested parties. of the Transparency in Lobbying, Non-Party My special thanks are due to all who took the Campaigning and Trade Union Administration trouble to respond to these questionnaires Act 2014 on 28 January 2015. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Unbecoming Silicon Valley: Techno Imaginaries and Materialities in Postsocialist Romania Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0vt9c4bq Author McElroy, Erin Mariel Brownstein Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ UNBECOMING SILICON VALLEY: TECHNO IMAGINARIES AND MATERIALITIES IN POSTSOCIALIST ROMANIA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in FEMINIST STUDIES by Erin Mariel Brownstein McElroy June 2019 The Dissertation of Erin McElroy is approved: ________________________________ Professor Neda Atanasoski, Chair ________________________________ Professor Karen Barad ________________________________ Professor Lisa Rofel ________________________________ Professor Megan Moodie ________________________________ Professor Liviu Chelcea ________________________________ Lori Kletzer Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Erin McElroy 2019 Table of Contents Abstract, iv-v Acknowledgements, vi-xi Introduction: Unbecoming Silicon Valley: Techno Imaginaries and Materialities in Postsocialist Romania, 1-44 Chapter 1: Digital Nomads in Siliconizing Cluj: Material and Allegorical Double Dispossession, 45-90 Chapter 2: Corrupting Techno-normativity in Postsocialist Romania: Queering Code and Computers, 91-127 Chapter 3: The Light Revolution, Blood Gold, and -

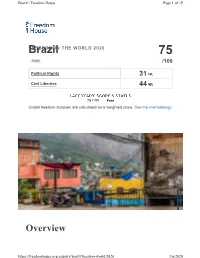

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

2016 General Election Results

Cumulative Report — Official Douglas County, Colorado — 2016 General Election — November 08, 2016 Page 1 of 9 11/22/2016 09:59 AM Total Number of Voters : 192,617 of 241,547 = 79.74% Precincts Reporting 0 of 157 = 0.00% Party Candidate Early Election Total Presidential Electors, Vote For 1 DEM Hillary Clinton / Tim Kaine 68,657 36.62% 0 0.00% 68,657 36.62% REP Donald J. Trump / Michael R. Pence 102,573 54.71% 0 0.00% 102,573 54.71% AMC Darrell L. Castle / Scott N. Bradley 695 0.37% 0 0.00% 695 0.37% LIB Gary Johnson / Bill Weld 10,212 5.45% 0 0.00% 10,212 5.45% GRE Jill Stein / Ajamu Baraka 1,477 0.79% 0 0.00% 1,477 0.79% APV Frank Atwood / Blake Huber 15 0.01% 0 0.00% 15 0.01% AMD "Rocky" Roque De La Fuente / Michael 45 0.02% 0 0.00% 45 0.02% Steinberg PRO James Hedges / Bill Bayes 7 0.00% 0 0.00% 7 0.00% AMR Tom Hoefling / Steve Schulin 37 0.02% 0 0.00% 37 0.02% VOA Chris Keniston / Deacon Taylor 253 0.13% 0 0.00% 253 0.13% SW Alyson Kennedy / Osborne Hart 13 0.01% 0 0.00% 13 0.01% IA Kyle Kenley Kopitke / Nathan R. Sorenson 64 0.03% 0 0.00% 64 0.03% KFP Laurence Kotlikoff / Edward Leamer 29 0.02% 0 0.00% 29 0.02% SAL Gloria Estela La Riva / Dennis J. Banks 10 0.01% 0 0.00% 10 0.01% Bradford Lyttle / Hannah Walsh 13 0.01% 0 0.00% 13 0.01% Joseph Allen Maldonado / Douglas K. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making.