Chaucer's Tale of Melibee As a Proverb Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studi Di Storia Medioevale E Di Diplomatica Nuova Serie Ii (2018)

STUDI DI STORIA MEDIOEVALE E DI DIPLOMATICA NUOVA SERIE II (2018) BRUNO MONDADORI Lettori di Albertano. Qualche spunto da un codice milanese del Trecento di Marina Gazzini in «Studi di Storia Medioevale e di Diplomatica», n.s. II (2018) Dipartimento di Studi Storici dell’Università degli Studi di Milano - Bruno Mondadori https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/SSMD ISSN 2611-318X ISBN 9788867743261 DOI 10.17464/9788867743261 Studi di Storia Medioevale e di Diplomatica, n.s. II (2018) Rivista del Dipartimento di Studi Storici - Università degli Studi di Milano <https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/SSMD> ISSN 2611-318X ISBN 9788867743261 DOI 10.17464/9788867743261 Lettori di Albertano. Qualche spunto da un codice milanese del Trecento Marina Gazzini La Biblioteca Trivulziana di Milano conserva un codice pergamenaceo contenen - te le opere latine – tre trattati (il Liber de amore et dilectione Dei et proximi ; il Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi ; il Liber consolationis et consilii ) e cinque sermoni con - fraternali – di Albertano da Brescia, giudice, politico e letterato attivo in età fe - dericiana 1 . Al codice, scritto in gotica libraria, è stata attribuita una datazione trecentesca, sia per gli aspetti formali sia per una data vergata in minuscola can - celleresca che compare sul verso della copertina anteriore: martedì 20 agosto 1381. In quel giorno il manoscritto risultava appartenere al cittadino milanese Antoniolo da Monza, al tempo rinchiuso nel carcere di Porta Romana su man - dato di Regina della Scala, moglie del signore di Milano Bernabò Visconti 2 . Antoniolo non fu l’unico proprietario del codice: sebbene venga ricordato sin - golarmente in tale ruolo anche nella pagina successiva del manoscritto 3 , nella 1 BTMi, ms. -

'In the Footsteps of the Ancients'

‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’: THE ORIGINS OF HUMANISM FROM LOVATO TO BRUNI Ronald G. Witt BRILL ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ STUDIES IN MEDIEVAL AND REFORMATION THOUGHT EDITED BY HEIKO A. OBERMAN, Tucson, Arizona IN COOPERATION WITH THOMAS A. BRADY, Jr., Berkeley, California ANDREW C. GOW, Edmonton, Alberta SUSAN C. KARANT-NUNN, Tucson, Arizona JÜRGEN MIETHKE, Heidelberg M. E. H. NICOLETTE MOUT, Leiden ANDREW PETTEGREE, St. Andrews MANFRED SCHULZE, Wuppertal VOLUME LXXIV RONALD G. WITT ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ THE ORIGINS OF HUMANISM FROM LOVATO TO BRUNI BY RONALD G. WITT BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2001 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Witt, Ronald G. ‘In the footsteps of the ancients’ : the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni / by Ronald G. Witt. p. cm. — (Studies in medieval and Reformation thought, ISSN 0585-6914 ; v. 74) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 9004113975 (alk. paper) 1. Lovati, Lovato de, d. 1309. 2. Bruni, Leonardo, 1369-1444. 3. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—Italy—History and criticism. 4. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—France—History and criticism. 5. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—Classical influences. 6. Rhetoric, Ancient— Study and teaching—History—To 1500. 7. Humanism in literature. 8. Humanists—France. 9. Humanists—Italy. 10. Italy—Intellectual life 1268-1559. 11. France—Intellectual life—To 1500. PA8045.I6 W58 2000 808’.0945’09023—dc21 00–023546 CIP Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Witt, Ronald G.: ‘In the footsteps of the ancients’ : the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni / by Ronald G. -

Disciplina Della Parola, Educazione Del Cittadino Analisi Del Liber De Doctrina Dicendi Et Tacendi Di Albertano Da Brescia*

Disciplina della parola, educazione del cittadino Analisi del Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi di Albertano da Brescia* Fabiana Fraulini (Università di Bologna) Between the 12th and the 13th century the institutional evolution that took place in the Italian Communes determines a change into the communicative practices. This phenomen was accompanied by a new consideration of speech. This paper examines the Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi, written by Albertanus of Brescia in 1245. According to this author, in order to guarantee common good and civil harmony, the power of language to affect both society and individuals requires rules and regulations that lead people to an ethical use of the speech. Keywords: Albertanus of Brescia, Italian Communes, Medieval Rethoric, Political Thought I. Una nuova disciplina della parola: retorica e politica nei comuni italiani La riflessione sulla lingua, la cui disciplina e custodia risultano fondamentali per il raggiungimento della salvezza eterna – «La morte e la vita sono nelle mani della lingua» [Prov. 18.21] –, ha accompagnato tutto il pensiero medievale. Le parole degli uomini, segnate dal peccato, devono cercare di assomigliare il più possibile alla parola divina, di cui restano comunque un’immagine imperfetta. Prerogativa della Chiesa, unica depositaria della parola di Dio, il dispositivo di valori e di norme che disciplina la parola viene, tra il XII e il XIII secolo, messo a dura prova dai cambiamenti avvenuti nell’articolazione sociale e nei bisogni culturali e religiosi delle collettività. -

New Latin Grammar

NEW LATIN GRAMMAR BY CHARLES E. BENNETT Goldwin Smith Professor of Latin in Cornell University Quicquid praecipies, esto brevis, ut cito dicta Percipiant animi dociles teneantque fideles: Omne supervacuum pleno de pectore manat. —HORACE, Ars Poetica. COPYRIGHT, 1895; 1908; 1918 BY CHARLES E. BENNETT PREFACE. The present work is a revision of that published in 1908. No radical alterations have been introduced, although a number of minor changes will be noted. I have added an Introduction on the origin and development of the Latin language, which it is hoped will prove interesting and instructive to the more ambitious pupil. At the end of the book will be found an Index to the Sources of the Illustrative Examples cited in the Syntax. C.E.B. ITHACA, NEW YORK, May 4, 1918 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The present book is a revision of my Latin Grammar originally published in 1895. Wherever greater accuracy or precision of statement seemed possible, I have endeavored to secure this. The rules for syllable division have been changed and made to conform to the prevailing practice of the Romans themselves. In the Perfect Subjunctive Active, the endings -īs, -īmus, -ītis are now marked long. The theory of vowel length before the suffixes -gnus, -gna, -gnum, and also before j, has been discarded. In the Syntax I have recognized a special category of Ablative of Association, and have abandoned the original doctrine as to the force of tenses in the Prohibitive. Apart from the foregoing, only minor and unessential modifications have been introduced. In its main lines the work remains unchanged. -

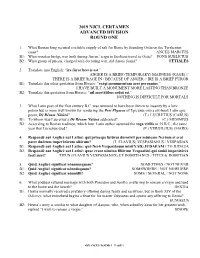

2019 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2019 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. What Roman king secured a reliable supply of salt for Rome by founding Ostia on the Tyrrhenian coast? ANCUS MARCIUS B1: What wooden bridge was built during Ancus’ reign to facilitate travel to Ostia? PONS SUBLICIUS B2: What group of priests, charged with declaring war, did Ancus found? FĒTIĀLĒS 2. Translate into English: “īra fūror brevis est.” ANGER IS A BRIEF (TEMPORARY) MADNESS (RAGE) // THERE IS A BRIEF RAGE IN / BECAUSE OF ANGER // IRE IS A BRIEF FUROR B1: Translate this other quotation from Horace: “exēgī monumentum aere perennius.” I HAVE BUILT A MONUMENT MORE LASTING THAN BRONZE B2: Translate this quotation from Horace: “nīl mortālibus arduī est.” NOTHING IS DIFFICULT FOR MORTALS 3. What Latin poet of the first century B.C. was rumored to have been driven to insanity by a love potion but is more well known for rendering the Peri Physeos of Epicurus into a six-book Latin epic poem, Dē Rērum Nātūrā? (T.) LUCRETIUS (CARUS) B1: To whom was Lucretius’s Dē Rērum Nātūrā addressed? (C.) MEMMIUS B2: According to Roman tradition, which later Latin author assumed the toga virīlis in 55 B.C., the same year that Lucretius died? (P.) VERGIL(IUS) (MARO) 4. Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quī prīnceps futūrus dormīvit per mūsicam Nerōnis et erat pater duōrum imperātōrum aliōrum? (T. FLAVIUS) VESPASIANUS / VESPASIAN B1: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latine: quō Nerō Vespasiānum mīsit?(AD) JUDAEAM / TO JUDAEA B2: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quae erant nōmina fīliōrum Vespasiānī quī ambō imperātōrēs factī sunt? TITUS (FLAVIUS VESPASIANUS) ET DOMITIANUS / TITUS & DOMITIAN 5. -

The Poems of Isabella Whitney: a Critical Edition

THE POEMS OF ISABELLA WHITNEY: A CRITICAL EDITION by MICHAEL DAVID FELKER, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved May 1990 (c) 1990, Michael David Felker ACKNOWLEDGMENT S I would like especially to thank the librarians and staff of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the British Library for their assistance and expertise in helping me trace the ownership of the two volumes of Isabella Whitney's poetry, and for their permission to make the poems of Isabella Whitney available to a larger audience. I would also like to thank the members of my committee. Dr. Kenneth Davis, Dr. Constance Kuriyama, Dr. Walter McDonald, Dr. Ernest Sullivan, and especially Dr. Donald Rude who contributed his knowledge and advice, and who provided constant encouragement throughout the lengthy process of researching and writing this dissertation. To my wife, who helped me collate and proof the texts until she knew them as well as I, I owe my greatest thanks. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE vi BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE viii BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE xxxviii INTRODUCTION Literary Tradition and the Conventions Ixii Prosody cvi NOTE ON EDITORIAL PRINCIPLES cxix THE POEMS The Copy of a Letter 1 [THE PRINTER TO the Reader] 2 I. W. To her vnconstant Louer 3 The admonition by the Auctor 10 [A Loueletter, sent from a faythful Louer] 16 [R W Against the wilfull Inconstancie of his deare Foe E. T. ] 22 A Sweet Nosgay 29 To the worshipfull and right vertuous yong Gentylman, GEORGE MAINWARING Esquier 30 The Auctor to the Reader 32 [T. -

Publilius Syrus, Maksymy Moralne – Sententiae

Aleksandra Szymańska, Ireneusz Żeber Żeber Ireneusz Szymańska, Aleksandra Opracowanie i przekład Opracowanie Dzięki talentom i umiejętnościom Aleksandry Szymańskiej i Ireneusza Żebera powstała praca nowatorska, wartościowa, wzbo- gacająca humanistykę. Praca ta przybliży polskiemu czytelnikowi mało dziś znaną twórczość Publiliusza Syrusa, cenionego w starożyt- nym Rzymie autora mimów literackich, który znakomicie opanował arkana sztuki scenicznej, a także kreatora (i chyba w pewnej mierze zbieracza) sentencji moralnych. [...] Szymańska i Żeber zarówno skrupulatnie wykorzystują odno- Publilius Syrus. Maksymy moralne – Sententiae moralne Maksymy Publilius Syrus. szące się do Publiliusza Syrusa źródła antyczne (wypowiedzi Pliniu- sza Starszego, Seneki Retora, Seneki Filozofa, Petroniusza Arbitra, Swetoniusza, Gelliusza, Makrobiusza), jak i późniejsze opracowania naukowe. Ich wywody są klarowne, interesujące, zespalające akade- Publilius Syrus micką uczoność z zamysłem popularyzatorskim. [...] Do tej pory brakowało pełnego przekładu maksym moralnych Maksymy moralne – Sententiae Publiliusza Syrusa na język polski. Ale dzięki wysiłkom Aleksandry Szymańskiej i Ireneusza Żebera mamy wreszcie taką translację, opa- trzoną indeksem rzeczowym. Opracowanie i przekład z recenzji wydawniczej dr. hab. Bogusława Bednarka, Uniwersytet Wrocławski Aleksandra Szymańska Ireneusz Żeber ISBN 978-83-66601-12-3 (oprawa twarda) ISBN 978-83-66601-00-0 (oprawa miękka) ISBN 978-83-66601-01-7 (online) Wrocław 2020 Publilius_Syrus_Maksymy_moralne_Sententiae_A5_cover_03_miekka.indd 1 24.06.2020 09:47:35 Publilius Syrus Maksymy moralne – Sententiae Prace Naukowe Wydziału Prawa, Administracji i Ekonomii Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego Seria: e-Monografie Nr 160 Dostęp online: https://www.repozytorium.uni.wroc.pl/publication/117779 DOI: 10.34616/23.20.022 Publilius Syrus Maksymy moralne – Sententiae Opracowanie i przekład Aleksandra Szymańska Uniwersytet Wrocławski ORCID: 0000-0003-0569-3005 Ireneusz Żeber Uniwersytet Wrocławski Wrocław 2020 Kolegium Redakcyjne prof. -

Early Sources Informing Leon Battista Alberti's De Pictura

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Alberti Before Florence: Early Sources Informing Leon Battista Alberti’s De Pictura A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Peter Francis Weller 2014 © Copyright by Peter Francis Weller 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Alberti Before Florence: Early Sources Informing Leon Battista Alberti’s De Pictura By Peter Francis Weller Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Charlene Villaseñor Black, Chair De pictura by Leon Battista Alberti (1404?-1472) is the earliest surviving treatise on visual art written in humanist Latin by an ostensible practitioner of painting. The book represents a definitive moment of cohesion between the two most conspicuous cultural developments of the early Renaissance, namely, humanism and the visual arts. This dissertation reconstructs the intellectual and visual environments in which Alberti moved before he entered Florence in the curia of Pope Eugenius IV in 1434, one year before the recorded date of completion of De pictura. For the two decades prior to his arrival in Florence, from 1414 to 1434, Alberti resided in Padua, Bologna, and Rome. Examination of specific textual and visual material in those cities – sources germane to Alberti’s humanist and visual development, and thus to the ideas put forth in De pictura – has been insubstantial. This dissertation will therefore present an investigation into the sources available to Alberti in Padua, Bologna and Rome, and will argue that this material helped to shape the prescriptions in Alberti’s canonical Renaissance tract. By more fully accounting for his intellectual and artistic progression before his arrival in Florence, this forensic reconstruction aims to fill a gap in our knowledge of Alberti’s formative years and thereby underline impact of his early career upon his development as an art theorist. -

Deliberative Rhetoric in the Twelfth Century: the Case for Eleanor of Aquitaine, Noblewomen, and the Ars Dictaminis

DELIBERATIVE RHETORIC IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY: THE CASE FOR ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE, NOBLEWOMEN, AND THE ARS DICTAMINIS Shawn D. Ramsey A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2012 Committee: Sue Carter Wood, Advisor Melissa K. Miller Graduate Faculty Representative Lance Massey Bruce L. Edwards James J. Murphy © 2012 Shawn D. Ramsey All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Sue Carter Wood, Advisor Medieval rhetoric has been negatively cast in traditional histories of rhetoric, and the role of women in the history of rhetoric and literate practice has been significantly underplayed and has been remiss in historicizing medieval women’s activities from the early and High Middle Ages. Deliberative rhetoric, too, has been significantly neglected as a division, a practice, and a genre of the medieval rhetorical tradition. This dissertation demonstrates that rhetoric in the twelfth century as practiced by women, was, in fact, highly public, civic, agonistic, designed for oral delivery, and concerned with civic matters at the highest levels of medieval culture and politics. It does so by examining letters from and to medieval women that relate to political matters in futuro, examining the roles created for women and the appeals used by women in their letters. It focuses special attention on the rhetoric of Eleanor of Aquitaine, but also many other female rhetors in the ars dictaminis tradition in the long twelfth century. In so doing, it shows that the earliest roots of rhetoric and writing instruction in fact pervaded a large number of political and diplomatic practices that were fundamentally civic and deliberative in nature. -

The Human Quest for Happiness and Meaning: Old and New Perspectives

Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts - Volume 5, Issue 2 – Pages 179-206 The Human Quest for Happiness and Meaning: Old and New Perspectives. Religious, Philosophical, and Literary Reflections from the Past as a Platform for Our Future – St. Augustine, Boethius, and Gautier de Coincy By Albrecht Classen Despite much ignorance (deliberate and accidental) and neglect, pre-modern literature, philosophy, and theology continue to matter greatly for us today. The quest for human happiness is never- ending, and each generation seems to go through the same process. But instead of re-inventing the proverbial wheel, we can draw on most influential and meaningful observations made already in late antiquity and the Middle Ages regarding how to pursue a good and hence a happy life. This paper examines the relevant treatises by St. Augustine and Boethius (late antiquity), and a religious tale by Gautier de Coincy (early thirteenth century). Each one of them already discussed at great length and in most convincing manner how human beings can work their way through false concepts and illusions and reach a higher level of epistemology and spirituality, expressed through the terms “happiness” and “goodness.” Introduction The Quest and Literature Ultimately, it seems, almost all efforts by people throughout time and all over the world focus on one and the same goal, as simple as that might sound: happiness. There is no purpose to life at all if misery and unhappiness rule and the daily routine consists of nothing but drudgery and pain that are not sustained by any relevance or meaning. Wherever we look, whatever text we read, whatever discourse we listen to, and however we ourselves try to make our own existence meaningful and hence successful, the struggle goes on and seems to be infinite. -

Europa E Italia. Studi in Onore Di Giorgio Chittolini

Europa e Italia. Studi in onore di Giorgio Chittolini Europe and Italy. Studies in honour of Giorgio Chittolini Firenze University Press 2011 Europa e Italia. Studi in onore di Giorgio Chittolini / Europe and Italy. Studies in honour of Giorgio Chittolini. – Firenze : Firenze university press, 2011. – XXXI, 453 p. ; 24 cm (Reti Medievali. E-Book ; 15) Accesso alla versione elettronica: http://www.ebook.retimedievali.it ISBN 978-88-6453-234-9 © 2011 Firenze University Press Università degli Studi di Firenze Firenze University Press Borgo Albizi, 28 50122 Firenze, Italy http://www.fupress.it/ Printed in Italy Indice Nota VII Tabula gratulatoria IX Bibliografia di Giorgio Chittolini, 1965-2009 XVII David Abulafia, Piombino between the great powers in the late fif - teenth century 3 Jane Black, Double duchy: the Sforza dukes and the other Lombard title 15 Robert Black, Notes on the date and genesis of Machiavelli’s De principatibus 29 Wim Blockmans, Cities, networks and territories. North-central Italy and the Low Countries reconsidered 43 Pio Caroni, Ius romanum in Helvetia : a che punto siamo? 55 Jean-Marie Cauchies, Justice épiscopale, justice communale. Délits de bourgeois et censures ecclésiastiques à Valenciennes (Hainaut) en 1424-1430 81 William J. Connell, New light on Machiavelli’s letter to Vettori, 10 December 1513 93 Elizabeth Crouzet-Pavan, Le seigneur et la ville : sur quelques usa - ges d’un dialogue (Italie, fin du Moyen Âge) 129 Trevor Dean, Knighthood in later medieval Italy 143 Gerhard Dilcher, Lega Lombarda und Rheinischer Städtebund. Ein Vergleich von Form und Funktion mittelalterlicher Städtebünde südlich und nördlich der Alpen 155 Arnold Esch, Il riflesso della grande storia nelle piccole vite: le sup - pliche alla Penitenzieria 181 Jean-Philippe Genet, État, État moderne, féodalisme d’état : quelques éclaircissements 195 James S. -

Shakespeare's Use of Proverbs for Characterization

SHAKESPEARE'S USE OF PROVERBS FOR CHARACTERIZATION, DRAJyiATIC ACTION, AND TONE IN REPRESENTATIVE COMEDY by EMMETT WAYNE COOK, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1974 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply indebted to Professor Joseph T. McCullen, Jr. for his direction of this dissertation and to the other members of my committee. Professors Warren S. Walker and Kenneth W. Davis, for their helpful criticism. 11 CONTENTS PREFACE 1 CHAPTER ONE: PROVERBS USED FOR CHARACTERIZATION. 12 I. The Falstaffian Figure 13 II. The Clown-Fool 32 III. The Malcontent 43 IV. The Comic Fop 47 V. Other Representative Comic Figures .... 57 CHAPTER TWO: PROVERBS USED IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF DRAMATIC ACTION 64 I. Proverbs Used to Reveal Past Action ... 66 II. Proverbs Used to Foreshadow Aspects of Character Development 73 III. Proverbs Used to Incite Action and Arouse Conflict 77 IV. Proverbs Used to Accentuate a Character's Method of Action 87 V. Proverbs Used to Expose the Immediate Dramatic Situation 98 VI. Proverbs Used to Convey a Sense of Anticipation of Action 110 VII. Proverbs Used as Devices for Sustain ing Comic Interlude 118 VIII. Proverbs Used as Devices for Greeting and Salutation 125 CHAPTER THREE: PROVERBS USED FOR SUSTAINING TONE . 130 CHAPTER FOXJR: CONCLUSION 164 BIBLIOGRAPHY 167 • • • 111 PREFACE One of the curiosities of historical and modern schol arship is the rather engaging matter of defining the obvious or familiar. Defining the common proverb truly illustrates such a statement.