Early Sources Informing Leon Battista Alberti's De Pictura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mappa Comuni.Pdf

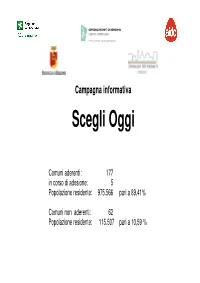

Campagna informativa Scegli Oggi Comuni aderenti : 177 in corso di adesione: 5 Popolazione residente: 975.566 pari a 89,41% Comuni non aderenti: 62 Popolazione residente: 115.507 pari a 10,59 % Comuni aderenti: Albano Sant'Alessandro – Albino – Almè - Almenno San Bartolomeo - Almenno San Salvatore - Alzano Lombardo – Ambivere – Comuni in corso di Arcene – Ardesio - Arzago d'Adda – Averara - adesione : Azzano San Paolo – Azzone – Barbata – Cenate Sopra – Clusone Bariano – Barzana – Berbenno – Bergamo – Entratico - Songavazzo Bianzano – Blello - Bolgare – Boltiere - – Vilminore di Scalve Bonate Sopra - Bonate Sotto – Bossico – Bottanuco – Bracca – Brembate - Brembate di Sopra – Brembilla - Brignano Gera d'Adda – Brusaporto – Calcinate – Calcio – Caluisco d’Adda - Calvenzano - Canonica d'Adda - Capriate San Gervasio – Caprino Bergamasco – Caravaggio - Carobbio degli Angeli – Comuni non Carvico – Casazza - Casirate d'Adda – aderenti : Casnigo - Castelli Calepio - Castione della Adrara San Martino - Presolana – Castro – Cavernago - Cenate Adrara San Rocco – Sotto - Cene – Cerete - Chignolo d'Isola – Algua – Antegnate – Chiuduno - Cisano Bergamasco – Ciserano - Aviatico - Bagnatica – Cividate al Piano – Colere - Cologno al Serio Bedulita - Berzo San – Colzate - Comun Nuovo - Corna Imagna – Fermo – Borgo di Terzo Cortenuova - Costa Volpino – Covo – Curno – – Branzi – Brumano - Cusio – Dalmine – Endine Gaiano - Fara Gera Camerata Cornello – d'Adda - Fara Olivana con Sola - Fino del Capizzone - Carona - Monte - Fiorano al Serio – Fontanella – -

Bologna Nei Libri D'arte

Comune di Bologna Biblioteca dell’Archiginnasio Bologna nei libri d’arte dei secoli XVI-XIX Biblioteca dell’Archiginnasio Piazza Galvani 1, 40124 Bologna www.archiginnasio.it L’immagine della copertina è tratta dal frontespizio del volume: GIAMPIETRO ZANOTTI, Le pitture di Pellegrino Tibaldi e di Niccolò Abbati esistenti nell’Instituto di Bologna descritte ed illustrate da Giampietro Zanotti segretario dell’Accademia Clementina, In Venetia, presso Giambatista Pasquali stampatore e libraio all’Insegna della felicità delle lettere, 1756. Comune di Bologna Biblioteca dell’Archiginnasio Bologna nei libri d’arte dei secoli XVI-XIX a cura di Cristina Bersani e Valeria Roncuzzi Biblioteca dell’Archiginnasio 16 settembre – 16 ottobre 2004 Bologna, 2004 L’esposizione organizzata dall’Archiginnasio rientra nel programma delle manifestazio- ni promosse in occasione del Festival del libro d’arte (Bologna, 17-19 settembre 2004). e si svolge col patrocinio del Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali Ministero degli Affari Esteri Alma Mater Studiorum Associazione Bancaria Italiana Associazione fra le Casse di Risparmio Italiane Si ringraziano per la collaborazione: Adriano Aldrovandi, Caterina Capra, Paola Ceccarelli, Saverio Ferrari, Vincenzo Lucchese, Sandra Saccone, Rita Zoppellari Un ringraziamento particolare a Pierangelo Bellettini e alla professoressa Maria Gioia Tavoni Allestimento: Franco Nicosia Floriano Boschi, Roberto Faccioli, Claudio Veronesi Fotografie: Fornasini Microfilm Service Ufficio Stampa: Valeria Roncuzzi Biblioteca dell’Archiginnasio Piazza Galvani 1, 40124 Bologna www.archiginnasio.it INFO: tel. 051 276811 - 051 276813; FAX 051 261160 Seconda edizione riveduta ed ampliata La proprietà artistica e letteraria di quanto qui pubblicato è riservata alla Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio di Bologna e per essa al Comune di Bologna. -

Studi Di Storia Medioevale E Di Diplomatica Nuova Serie Ii (2018)

STUDI DI STORIA MEDIOEVALE E DI DIPLOMATICA NUOVA SERIE II (2018) BRUNO MONDADORI Lettori di Albertano. Qualche spunto da un codice milanese del Trecento di Marina Gazzini in «Studi di Storia Medioevale e di Diplomatica», n.s. II (2018) Dipartimento di Studi Storici dell’Università degli Studi di Milano - Bruno Mondadori https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/SSMD ISSN 2611-318X ISBN 9788867743261 DOI 10.17464/9788867743261 Studi di Storia Medioevale e di Diplomatica, n.s. II (2018) Rivista del Dipartimento di Studi Storici - Università degli Studi di Milano <https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/SSMD> ISSN 2611-318X ISBN 9788867743261 DOI 10.17464/9788867743261 Lettori di Albertano. Qualche spunto da un codice milanese del Trecento Marina Gazzini La Biblioteca Trivulziana di Milano conserva un codice pergamenaceo contenen - te le opere latine – tre trattati (il Liber de amore et dilectione Dei et proximi ; il Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi ; il Liber consolationis et consilii ) e cinque sermoni con - fraternali – di Albertano da Brescia, giudice, politico e letterato attivo in età fe - dericiana 1 . Al codice, scritto in gotica libraria, è stata attribuita una datazione trecentesca, sia per gli aspetti formali sia per una data vergata in minuscola can - celleresca che compare sul verso della copertina anteriore: martedì 20 agosto 1381. In quel giorno il manoscritto risultava appartenere al cittadino milanese Antoniolo da Monza, al tempo rinchiuso nel carcere di Porta Romana su man - dato di Regina della Scala, moglie del signore di Milano Bernabò Visconti 2 . Antoniolo non fu l’unico proprietario del codice: sebbene venga ricordato sin - golarmente in tale ruolo anche nella pagina successiva del manoscritto 3 , nella 1 BTMi, ms. -

Saint Dominic

Saint Dominic For the village in Cornwall, see St Dominic, Cornwall. For Places and churches named after St Dominic, see St Dominic (Disambiguation). Saint Dominic (Spanish: Santo Domingo), also known as Dominic of Osma and Dominic of Caleruega, of- ten called Dominic de Guzmán and Domingo Félix de Guzmán (1170 – August 6, 1221), was a Spanish priest and founder of the Dominican Order. Dominic is the patron saint of astronomers. 1 Life 1.1 Birth and parentage Dominic was born in Caleruega,[3] halfway between Osma and Aranda de Duero in Old Castile, Spain. He was named after Saint Dominic of Silos, who is said to be the patron saint of hopeful mothers. The Benedictine abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos lies a few miles north of Caleruega. In the earliest narrative source, by Jordan of Saxony, Do- minic’s parents are not named. The story is told that be- Saint Dominic saw the need for a new type of organization to fore his birth his barren mother made a pilgrimage to Si- address the spiritual needs of the growing cities of the era, one los and dreamed that a dog leapt from her womb carry- that would combine dedication and systematic education, with ing a torch in its mouth, and “seemed to set the earth on more organizational flexibility than either monastic orders or the fire”. This story is likely to have emerged when his order secular clergy. became known, after his name, as the Dominican order, Dominicanus in Latin and a play on words interpreted as 1.2 Education and early career Domini canis: “Dog of the Lord.” Jordan adds that Do- minic was brought up by his parents and a maternal uncle who was an archbishop.[4] He was named in honour of Dominic was educated in the schools of Palencia (they Dominic of Silos. -

Perspective As a Convention of Spatial Objects Representation

TECHNICAL TRANSACTIONS CZASOPISMO TECHNICZNE ARCHITECTURE ARCHITEKTURA 11-A/2015 ANNA KULIG*, KRYSTYNA ROMANIAK** PERSPECTIVE AS A CONVENTION OF SPATIAL OBJECTS REPRESENTATION PERSPEKTYWA JAKO KONWENCJA PRZEDSTAWIANIA OBIEKTÓW PRZESTRZENNYCH Abstract In this study perspective was presented as one of the conventions for recording 3D objects on a 2D plane. Being the easiest type of projection to understand (for a recipient) perspective, in its historical context, was presented from ancient times until today1. Issues of practice and theory were addressed and examples of precise compliance with the rules and their negation in the 20th century were presented. Contemporary practical applications in architecture were reviewed. Keywords: linear perspective, computer perspective visualization Streszczenie W pracy przedstawiono perspektywę jako jedną z konwencji notowania trójwymiarowych obiektów na dwuwymiarowej płaszczyźnie. Perspektywę, jako najbardziej zrozumiały dla odbiorcy rodzaj rzutowania, zaprezentowano w ujęciu historycznym (od antyku do czasów współczesnych). Odniesiono się do praktyki i teorii, przykładów ścisłego stosowania reguł i ne- gowania ich w XX wieku. Przywołano współczesne zastosowania praktyczne w architekturze. Słowa kluczowe: perspektywa liniowa, komputerowe wizualizacje perspektywiczne * Ph.D. Arch. Anna Kulig, Assoc. Prof. D.Sc. Ph.D. Krystyna Romaniak, Faculty of Architecture, Cracow University of Technology; [email protected], [email protected]. 1 In his work [21] Michał Sufczyński presents the development of the recording methods in architectural design (Chapter XI, p. 78). The analysis based on works [4] and [11] covers from earliest times up to today. 20 1. Introduction Spatial objects are observed in three dimensions – we view them from different sides and directions. „For each look, new shapes of the dimensions sizes and lines are brought. -

'In the Footsteps of the Ancients'

‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’: THE ORIGINS OF HUMANISM FROM LOVATO TO BRUNI Ronald G. Witt BRILL ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ STUDIES IN MEDIEVAL AND REFORMATION THOUGHT EDITED BY HEIKO A. OBERMAN, Tucson, Arizona IN COOPERATION WITH THOMAS A. BRADY, Jr., Berkeley, California ANDREW C. GOW, Edmonton, Alberta SUSAN C. KARANT-NUNN, Tucson, Arizona JÜRGEN MIETHKE, Heidelberg M. E. H. NICOLETTE MOUT, Leiden ANDREW PETTEGREE, St. Andrews MANFRED SCHULZE, Wuppertal VOLUME LXXIV RONALD G. WITT ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ THE ORIGINS OF HUMANISM FROM LOVATO TO BRUNI BY RONALD G. WITT BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2001 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Witt, Ronald G. ‘In the footsteps of the ancients’ : the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni / by Ronald G. Witt. p. cm. — (Studies in medieval and Reformation thought, ISSN 0585-6914 ; v. 74) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 9004113975 (alk. paper) 1. Lovati, Lovato de, d. 1309. 2. Bruni, Leonardo, 1369-1444. 3. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—Italy—History and criticism. 4. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—France—History and criticism. 5. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—Classical influences. 6. Rhetoric, Ancient— Study and teaching—History—To 1500. 7. Humanism in literature. 8. Humanists—France. 9. Humanists—Italy. 10. Italy—Intellectual life 1268-1559. 11. France—Intellectual life—To 1500. PA8045.I6 W58 2000 808’.0945’09023—dc21 00–023546 CIP Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Witt, Ronald G.: ‘In the footsteps of the ancients’ : the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni / by Ronald G. -

Robert Zwijnenberg Introduction Leon Battista Alberti's Treatise De Pictura

WHY DID ALBERTI NOT ILLUSTRATE HIS DE PICTURA? Robert Zwijnenberg Introduction Leon Battista Alberti's treatise De Pictura (1435-36) is best understood as an attempt to elevate painting from its lowly position as a craft, which it still had in Italy at the beginning of the fifteenth century, and endow it with the status of a liberal art. Alberti sought to restore the glory which painting enjoyed in Antiquity. To accomplish this goal, it was necessary to invent a theoretical foundation for it, includ ing a specific technical vocabulary for discussing painting as a lib eral art. The liberal arts differ from the mechanical arts precisely in that they are based on general theoretical principles. For such prin ciples and vocabulary Alberti relied on two disciplines that were available to him in particular: mathematics, which he deployed for discussing the quantifiable aspects of painting, and rhetoric, by which he could elaborate subjects associated with form, content and com position, as well as with the relation between paintings and their viewers. Specifically, Alberti tried to achieve his aim by concentrat ing his discourse in De Pictura on linear perspective and its use of optical and geometrical principles; on an analysis of pictorial com position that is couched in rhetorical terms; and on the connection between painting and poetry with respect to the proper selection and representation of subjects as well as regarding advice on the proper education and attitude of the painter. On account of his decidedly theoretical focus, he succeeded not only in giving painting the sta tus of a liberal art, but also in making painting an appropriate sub ject for civilized, humanist thought and discussion.* The author himself repeatedly emphasized the novel character of his project. -

Disciplina Della Parola, Educazione Del Cittadino Analisi Del Liber De Doctrina Dicendi Et Tacendi Di Albertano Da Brescia*

Disciplina della parola, educazione del cittadino Analisi del Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi di Albertano da Brescia* Fabiana Fraulini (Università di Bologna) Between the 12th and the 13th century the institutional evolution that took place in the Italian Communes determines a change into the communicative practices. This phenomen was accompanied by a new consideration of speech. This paper examines the Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi, written by Albertanus of Brescia in 1245. According to this author, in order to guarantee common good and civil harmony, the power of language to affect both society and individuals requires rules and regulations that lead people to an ethical use of the speech. Keywords: Albertanus of Brescia, Italian Communes, Medieval Rethoric, Political Thought I. Una nuova disciplina della parola: retorica e politica nei comuni italiani La riflessione sulla lingua, la cui disciplina e custodia risultano fondamentali per il raggiungimento della salvezza eterna – «La morte e la vita sono nelle mani della lingua» [Prov. 18.21] –, ha accompagnato tutto il pensiero medievale. Le parole degli uomini, segnate dal peccato, devono cercare di assomigliare il più possibile alla parola divina, di cui restano comunque un’immagine imperfetta. Prerogativa della Chiesa, unica depositaria della parola di Dio, il dispositivo di valori e di norme che disciplina la parola viene, tra il XII e il XIII secolo, messo a dura prova dai cambiamenti avvenuti nell’articolazione sociale e nei bisogni culturali e religiosi delle collettività. -

Cna85b2317313.Pdf

THE PAINTERS OF THE SCHOOL OF FERRARA BY EDMUND G. .GARDNER, M.A. AUTHOR OF "DUKES AND POETS IN FERRARA" "SAINT CATHERINE OF SIENA" ETC LONDON : DUCKWORTH AND CO. NEW YORK : CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO FRANK ROOKE LEY PREFACE Itf the following pages I have attempted to give a brief account of the famous school of painting that originated in Ferrara about the middle of the fifteenth century, and thence not only extended its influence to the other cities that owned the sway of the House of Este, but spread over all Emilia and Romagna, produced Correggio in Parma, and even shared in the making of Raphael at Urbino. Correggio himself is not included : he is too great a figure in Italian art to be treated as merely the member of a local school ; and he has already been the subject of a separate monograph in this series. The classical volumes of Girolamo Baruffaldi are still indispensable to the student of the artistic history of Ferrara. It was, however, Morelli who first revealed the importance and significance of the Perrarese school in the evolution of Italian art ; and, although a few of his conclusions and conjectures have to be abandoned or modified in the light of later researches and dis- coveries, his work must ever remain our starting-point. vii viii PREFACE The indefatigable researches of Signor Adolfo Venturi have covered almost every phase of the subject, and it would be impossible for any writer now treating of Perrarese painting to overstate the debt that he must inevitably owe to him. -

El Greco at the Ophthalmologist's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AIR Universita degli studi di Milano Predella journal of visual arts, n°35, 2014 - Miscellanea / Miscellany www.predella.it / predella.cfs.unipi.it Direzione scienti" ca e proprieta ̀ / Scholarly Editors-in-Chief and owners: Gerardo de Simone , Emanuele Pellegrini - [email protected] Predella pubblica ogni anno due numeri online e due numeri monogra" ci a stampa / Predella publishes two online issues and two monographic print issues each year Tutti gli articoli sono sottoposti alla peer-review anonima / All articles are subject to anonymous peer-review Comitato scienti" co / Editorial Advisory Board : Diane Bodart, Maria Luisa Catoni, Michele Dantini, Annamaria Ducci, Fabio Marcelli, Linda Pisani, Riccardo Venturi Cura redazionale e impaginazione / Editing & Layout: Paolo di Simone Predella journal of visual arts - ISSN 1827-8655 pubblicato nel mese di Ottobre 2015 / published in the month of October 2015 Andrea Pinotti El Greco at the Ophthalmologist’s The paper aims at reconstructing the centennial history of the so-called “El Greco fallacy”, namely the hy- pothesis that the extremely elongated gures painted by the Cretan artist were due to his astigmatism and not to a stylistic option intentionally assumed by the painter. This hypothesis interestingly and prob- lematically intertwines the status of the perceptual image with the status of the represented picture. While o ering a survey of the main positions defended by ophthalmologists, psychologists, art critics and art historians on this optical issue, the essay tries to reject the false alternative between a physiologistic and a spiritualistic approach to art, both based on an unsustainable causalistic assumption. -

El Museo De Copias» Copias» De Museo «El , Exhibida En El El En , Exhibida

UC CHILE — ARQ 95 1 Reportaje Fotográfico / Photo Report Palabras clave Reproducción Imitación El Museo dE CopiaS Pedagogía Bellas Artes Chile Texto de / Text by: Fotografías de / Pictures by: gloria CorTéS CristiaN valenzuEla Curadora, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago, Chile Como herramienta pedagógica dirigida * «El Museo de Copias» fue parte de la exposición al intelecto, la copia de modelos Tránsitos, exhibida en el preexistentes – referentes – era una Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Chile entre práctica habitual en el siglo xix. A partir de el 14 de julio y el 31 de la colección de reproducciones acumulada diciembre de 2016. durante el período previo a la creación del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Chile, esta exposición revaloriza el rol de estas réplicas en un momento en que nociones como creatividad u originalidad se encuentran en tela de juicio. 9 REPORT PHOTO — REPORTAJE FOTOGRÁFICO 1 (pág. anterior / previous page) Manufactura de Signa. Cabeza de David, c. 1900. Terracota, 110 × 67 × 60 cm. Reproducción (frag- mento) del original de Mi- guel Ángel (1475-1564) entre 1501 y 1504. Actualmente es expuesta en la Galería de la Academia de Florencia. Atrás se pueden apreciar: Henriette Petit, Juventud, Goya, Bacante con Rosas, Ippolita María Sforza, Ma- rietta Strozzi, Nefertiti, Ma- tilde Sotomayor y Venus de Arles, entre otros. / Signa manufacture. David’s head, c. 1900. Terracotta, 110 × 67 × 60 cm. Reproduction (fragment) of Michelan- gelo’s original (1475-1564) developed between 1501 and 1504. Currently exhibited at the Gallery of the Academy of Florence. In the back: Henriette Petit, Juventud, Goya, Bacchante with Roses, Ippolita Maria Sforza, Ma- rietta Strozzi, Nefertiti, Ma- tilde Sotomayor and Venus of Arles, among others. -

A One-Semester Art History Course Outline for High School Students

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1965 A One-Semester Art History Course Outline for High School Students Patricia R. Grover Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Secondary Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Grover, Patricia R., "A One-Semester Art History Course Outline for High School Students" (1965). All Master's Theses. 455. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/455 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A ONE-SEMESTER ART HISTORY COURSE ourLINB FOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDEN.rS A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Patricia R. Grover July 1965 • i ". ';. i:.; ~-ccb <,...6-0J £'Tl..J.,g. G'I APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ Edward C. Haines, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ Louis A. Kollmeyer _________________________________ Clifford Erickson ACKNOWLBDGMENI' I wish to express my appreciation to all the members of my committee for the assistance they have given me, Mr. Haines, Dr. Brickson and Dr. Kollmeyer. Patricia R. Grover TABLE Of CONTENTS