Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studi Di Storia Medioevale E Di Diplomatica Nuova Serie Ii (2018)

STUDI DI STORIA MEDIOEVALE E DI DIPLOMATICA NUOVA SERIE II (2018) BRUNO MONDADORI Lettori di Albertano. Qualche spunto da un codice milanese del Trecento di Marina Gazzini in «Studi di Storia Medioevale e di Diplomatica», n.s. II (2018) Dipartimento di Studi Storici dell’Università degli Studi di Milano - Bruno Mondadori https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/SSMD ISSN 2611-318X ISBN 9788867743261 DOI 10.17464/9788867743261 Studi di Storia Medioevale e di Diplomatica, n.s. II (2018) Rivista del Dipartimento di Studi Storici - Università degli Studi di Milano <https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/SSMD> ISSN 2611-318X ISBN 9788867743261 DOI 10.17464/9788867743261 Lettori di Albertano. Qualche spunto da un codice milanese del Trecento Marina Gazzini La Biblioteca Trivulziana di Milano conserva un codice pergamenaceo contenen - te le opere latine – tre trattati (il Liber de amore et dilectione Dei et proximi ; il Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi ; il Liber consolationis et consilii ) e cinque sermoni con - fraternali – di Albertano da Brescia, giudice, politico e letterato attivo in età fe - dericiana 1 . Al codice, scritto in gotica libraria, è stata attribuita una datazione trecentesca, sia per gli aspetti formali sia per una data vergata in minuscola can - celleresca che compare sul verso della copertina anteriore: martedì 20 agosto 1381. In quel giorno il manoscritto risultava appartenere al cittadino milanese Antoniolo da Monza, al tempo rinchiuso nel carcere di Porta Romana su man - dato di Regina della Scala, moglie del signore di Milano Bernabò Visconti 2 . Antoniolo non fu l’unico proprietario del codice: sebbene venga ricordato sin - golarmente in tale ruolo anche nella pagina successiva del manoscritto 3 , nella 1 BTMi, ms. -

'In the Footsteps of the Ancients'

‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’: THE ORIGINS OF HUMANISM FROM LOVATO TO BRUNI Ronald G. Witt BRILL ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ STUDIES IN MEDIEVAL AND REFORMATION THOUGHT EDITED BY HEIKO A. OBERMAN, Tucson, Arizona IN COOPERATION WITH THOMAS A. BRADY, Jr., Berkeley, California ANDREW C. GOW, Edmonton, Alberta SUSAN C. KARANT-NUNN, Tucson, Arizona JÜRGEN MIETHKE, Heidelberg M. E. H. NICOLETTE MOUT, Leiden ANDREW PETTEGREE, St. Andrews MANFRED SCHULZE, Wuppertal VOLUME LXXIV RONALD G. WITT ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ THE ORIGINS OF HUMANISM FROM LOVATO TO BRUNI BY RONALD G. WITT BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2001 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Witt, Ronald G. ‘In the footsteps of the ancients’ : the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni / by Ronald G. Witt. p. cm. — (Studies in medieval and Reformation thought, ISSN 0585-6914 ; v. 74) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 9004113975 (alk. paper) 1. Lovati, Lovato de, d. 1309. 2. Bruni, Leonardo, 1369-1444. 3. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—Italy—History and criticism. 4. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—France—History and criticism. 5. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—Classical influences. 6. Rhetoric, Ancient— Study and teaching—History—To 1500. 7. Humanism in literature. 8. Humanists—France. 9. Humanists—Italy. 10. Italy—Intellectual life 1268-1559. 11. France—Intellectual life—To 1500. PA8045.I6 W58 2000 808’.0945’09023—dc21 00–023546 CIP Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Witt, Ronald G.: ‘In the footsteps of the ancients’ : the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni / by Ronald G. -

Disciplina Della Parola, Educazione Del Cittadino Analisi Del Liber De Doctrina Dicendi Et Tacendi Di Albertano Da Brescia*

Disciplina della parola, educazione del cittadino Analisi del Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi di Albertano da Brescia* Fabiana Fraulini (Università di Bologna) Between the 12th and the 13th century the institutional evolution that took place in the Italian Communes determines a change into the communicative practices. This phenomen was accompanied by a new consideration of speech. This paper examines the Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi, written by Albertanus of Brescia in 1245. According to this author, in order to guarantee common good and civil harmony, the power of language to affect both society and individuals requires rules and regulations that lead people to an ethical use of the speech. Keywords: Albertanus of Brescia, Italian Communes, Medieval Rethoric, Political Thought I. Una nuova disciplina della parola: retorica e politica nei comuni italiani La riflessione sulla lingua, la cui disciplina e custodia risultano fondamentali per il raggiungimento della salvezza eterna – «La morte e la vita sono nelle mani della lingua» [Prov. 18.21] –, ha accompagnato tutto il pensiero medievale. Le parole degli uomini, segnate dal peccato, devono cercare di assomigliare il più possibile alla parola divina, di cui restano comunque un’immagine imperfetta. Prerogativa della Chiesa, unica depositaria della parola di Dio, il dispositivo di valori e di norme che disciplina la parola viene, tra il XII e il XIII secolo, messo a dura prova dai cambiamenti avvenuti nell’articolazione sociale e nei bisogni culturali e religiosi delle collettività. -

An Exploration of Gender, Sexuality and Queerness in Cis- Female Drag Queen Performance

School of Media, Culture & Creative Arts Faux Queens: an exploration of gender, sexuality and queerness in cis- female drag queen performance. Jamie Lee Coull This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University November 2015 DECLARATION To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Human Ethics The research presented and reported in this thesis was conducted in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007) – updated March 2014. The proposed research study received human research ethics approval from the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (EC00262), Approval Number #MCCA-12-12. Signature: Date: 20/11/2015 i ABSTRACT This PhD thesis investigates the cultural implications of cis-women performing female drag, with particular focus on cis-female drag queens (aka faux queens) who are straight-identified. The research has been completed as creative production and exegesis, and both products address the central research question. In the introductory chapter I contextualise the theatrical history of male-to-female drag beginning with the Ancient Greek stage, and foreground faux queens as the subject of investigation. I also outline the methodology employed, including practice-led research, autoethnography, and in-depth interview, and provide a summary of each chapter and the creative production Agorafaux-pas! - A drag cabaret. The introduction presents the cultural implications of faux queens that are also explored in the chapters and creative production. -

New Latin Grammar

NEW LATIN GRAMMAR BY CHARLES E. BENNETT Goldwin Smith Professor of Latin in Cornell University Quicquid praecipies, esto brevis, ut cito dicta Percipiant animi dociles teneantque fideles: Omne supervacuum pleno de pectore manat. —HORACE, Ars Poetica. COPYRIGHT, 1895; 1908; 1918 BY CHARLES E. BENNETT PREFACE. The present work is a revision of that published in 1908. No radical alterations have been introduced, although a number of minor changes will be noted. I have added an Introduction on the origin and development of the Latin language, which it is hoped will prove interesting and instructive to the more ambitious pupil. At the end of the book will be found an Index to the Sources of the Illustrative Examples cited in the Syntax. C.E.B. ITHACA, NEW YORK, May 4, 1918 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The present book is a revision of my Latin Grammar originally published in 1895. Wherever greater accuracy or precision of statement seemed possible, I have endeavored to secure this. The rules for syllable division have been changed and made to conform to the prevailing practice of the Romans themselves. In the Perfect Subjunctive Active, the endings -īs, -īmus, -ītis are now marked long. The theory of vowel length before the suffixes -gnus, -gna, -gnum, and also before j, has been discarded. In the Syntax I have recognized a special category of Ablative of Association, and have abandoned the original doctrine as to the force of tenses in the Prohibitive. Apart from the foregoing, only minor and unessential modifications have been introduced. In its main lines the work remains unchanged. -

Old English Ecologies: Environmental Readings of Anglo-Saxon Texts and Culture

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2013 Old English Ecologies: Environmental Readings of Anglo-Saxon Texts and Culture Ilse Schweitzer VanDonkelaar Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation VanDonkelaar, Ilse Schweitzer, "Old English Ecologies: Environmental Readings of Anglo-Saxon Texts and Culture" (2013). Dissertations. 216. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/216 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OLD ENGLISH ECOLOGIES: ENVIRONMENTAL READINGS OF ANGLO-SAXON TEXTS AND CULTURE by Ilse Schweitzer VanDonkelaar A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Western Michigan University December 2013 Doctoral Committee: Jana K. Schulman, Ph.D., Chair Eve Salisbury, Ph.D. Richard Utz, Ph.D. Sarah Hill, Ph.D. OLD ENGLISH ECOLOGIES: ENVIRONMENTAL READINGS OF ANGLO-SAXON TEXTS AND CULTURE Ilse Schweitzer VanDonkelaar, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2013 Conventionally, scholars have viewed representations of the natural world in Anglo-Saxon (Old English) literature as peripheral, static, or largely symbolic: a “backdrop” before which the events of human and divine history unfold. In “Old English Ecologies,” I apply the relatively new critical perspectives of ecocriticism and place- based study to the Anglo-Saxon canon to reveal the depth and changeability in these literary landscapes. -

Rites of Passage and Oral Storytelling in Romanian Epic and the New Testament

Oral Tradition, 17/2 (2002): 236-258 Rites of Passage and Oral Storytelling in Romanian Epic and the New Testament Margaret H. Beissinger The exploration of traditional narratives that circulated in the pre- modern age through the comparative study of contemporary genres has a rich precedent in the groundbreaking work of Milman Parry and Albert Lord. Starting in the 1930s, Parry and Lord sought to gain insight into the compositional style of the Homeric epics by observing and analyzing Yugoslav oral epic poets and their poetry. Their findings and conclusions were seminal. In 1960, Lord posited that traditional singers compose long sung poetry in isometric verses in performance through their reliance on groups of words that are regularly used-—as parts of lines, entire lines, and groups of lines—to represent ideas in the poetry.1 This became known as the theory of oral-formulaic composition and has had profound implications in the study of epic and other traditional genres from ancient to modern times.2 Oral epic is no longer performed in today’s former Yugoslavia. But there are still traces of traditional narrative poetry elsewhere in the Balkans, namely in southern Romania, where I have done much fieldwork among epic singers and at epic performances. Though greatly inspired by the work of Parry and Lord, my goals in this article, of course, are far humbler. I examine narrative patterns in a Romanian epic song cycle in order to offer possible models for the further study of oral storytelling in the New Testament. My exploration centers on epics of initiation and the nature of the initiatory hero. -

Der Bergkranz

(eBook - Digi20-Retro) Petar II Petrovic Njegoš Der Bergkranz Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. 00053882 / V PETAR IL PETROVIC NJEGOS Der Bergkranz »• Einleitung, Übersetzung und Kommentar von ■» Л Л A. Schmaus 196} VERLAG OTTO SAGNER, MÜNCHEN PROSVETA VERLAG. BELGRAD © 1963 by Verlag O tto Sagner/München Abteilung der Fa. Kubon & Sagner, München Herstellung: Buch- und Offsetdruckerei Karl Schmidle, Ebersberg Printed in Germany EINLEITUNG ■ Щ Petar II. Petrovié Njegoš 1813— 1851 I Leben и n d p о 1 i t i s с h e s Wirken Njegoš stammte aus dem montenegrinischen Dorfe Njeguži unterhalb des Lovcen, aus der Familie Petrovié, in der sich seit dem Ende des 17. Jahr- hunderts die Bischofswürde forterbte. 1813 geboren, war der junge Rade — dies war sein Taufname — zunächst nicht zum Bischofsamte aus- ersehen, sondern wurde erst 1826 von seinem Onkel, Petar I., zum Nach- folger bestimmt. Damit fand die sorglose Kindheit ein jähes Ende. Im Kloster von Cetinje und anschließend in Topla bei Hercegnovi erhielt er die für sein künftiges Amt notwendige Ausbildung; wegen der Kürze der Zeit und des Fehlens sonstiger Voraussetzungen konnte sie weder sehr umfassend noch sehr gründlich sein. Vielfältige Anregungen wurden jedoch dem künftigen Dichter durch den serbischen Freiheitskämpfer und damals schon berühmten Poeten Sima Milutinovié vermittelt, der 1827 sein Amt als Sekretär des Bischofs und Lehrer des jungen Rade antrat. -

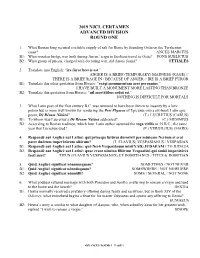

2019 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2019 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. What Roman king secured a reliable supply of salt for Rome by founding Ostia on the Tyrrhenian coast? ANCUS MARCIUS B1: What wooden bridge was built during Ancus’ reign to facilitate travel to Ostia? PONS SUBLICIUS B2: What group of priests, charged with declaring war, did Ancus found? FĒTIĀLĒS 2. Translate into English: “īra fūror brevis est.” ANGER IS A BRIEF (TEMPORARY) MADNESS (RAGE) // THERE IS A BRIEF RAGE IN / BECAUSE OF ANGER // IRE IS A BRIEF FUROR B1: Translate this other quotation from Horace: “exēgī monumentum aere perennius.” I HAVE BUILT A MONUMENT MORE LASTING THAN BRONZE B2: Translate this quotation from Horace: “nīl mortālibus arduī est.” NOTHING IS DIFFICULT FOR MORTALS 3. What Latin poet of the first century B.C. was rumored to have been driven to insanity by a love potion but is more well known for rendering the Peri Physeos of Epicurus into a six-book Latin epic poem, Dē Rērum Nātūrā? (T.) LUCRETIUS (CARUS) B1: To whom was Lucretius’s Dē Rērum Nātūrā addressed? (C.) MEMMIUS B2: According to Roman tradition, which later Latin author assumed the toga virīlis in 55 B.C., the same year that Lucretius died? (P.) VERGIL(IUS) (MARO) 4. Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quī prīnceps futūrus dormīvit per mūsicam Nerōnis et erat pater duōrum imperātōrum aliōrum? (T. FLAVIUS) VESPASIANUS / VESPASIAN B1: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latine: quō Nerō Vespasiānum mīsit?(AD) JUDAEAM / TO JUDAEA B2: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quae erant nōmina fīliōrum Vespasiānī quī ambō imperātōrēs factī sunt? TITUS (FLAVIUS VESPASIANUS) ET DOMITIANUS / TITUS & DOMITIAN 5. -

The Poems of Isabella Whitney: a Critical Edition

THE POEMS OF ISABELLA WHITNEY: A CRITICAL EDITION by MICHAEL DAVID FELKER, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved May 1990 (c) 1990, Michael David Felker ACKNOWLEDGMENT S I would like especially to thank the librarians and staff of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the British Library for their assistance and expertise in helping me trace the ownership of the two volumes of Isabella Whitney's poetry, and for their permission to make the poems of Isabella Whitney available to a larger audience. I would also like to thank the members of my committee. Dr. Kenneth Davis, Dr. Constance Kuriyama, Dr. Walter McDonald, Dr. Ernest Sullivan, and especially Dr. Donald Rude who contributed his knowledge and advice, and who provided constant encouragement throughout the lengthy process of researching and writing this dissertation. To my wife, who helped me collate and proof the texts until she knew them as well as I, I owe my greatest thanks. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE vi BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE viii BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE xxxviii INTRODUCTION Literary Tradition and the Conventions Ixii Prosody cvi NOTE ON EDITORIAL PRINCIPLES cxix THE POEMS The Copy of a Letter 1 [THE PRINTER TO the Reader] 2 I. W. To her vnconstant Louer 3 The admonition by the Auctor 10 [A Loueletter, sent from a faythful Louer] 16 [R W Against the wilfull Inconstancie of his deare Foe E. T. ] 22 A Sweet Nosgay 29 To the worshipfull and right vertuous yong Gentylman, GEORGE MAINWARING Esquier 30 The Auctor to the Reader 32 [T. -

External Content.Pdf

The Contemporary Medieval in Practice SPOTLIGHTS Series Editor: Timothy Mathews, Emeritus Professor of French and Com- parative Criticism, UCL Spotlights is a short monograph series for authors wishing to make new or defining elements of their work accessible to a wide audience. The series provides a responsive forum for researchers to share key develop- ments in their discipline and reach across disciplinary boundaries. The series also aims to support a diverse range of approaches to undertaking research and writing it. The Contemporary Medieval in Practice Clare A. Lees and Gillian R. Overing First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Text © Authors, 2019 Images © Copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non- derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Lees, C.A., and Overing, G.R. 2019. The Contemporary Medieval in Practice. London: UCL Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787354654 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. -

House of Yes Alice

Margo MacDonald • Dmanda Tension • Roy Mitchell esented by PinkPlayMags www.thebuzzmag.ca Pr House of Yes Brooklyn’s Party Central Alice Bag For daily and weekly event listings visit Advocating Through Music JUNE 2020 / JULY 2020 *** free *** TLC Pet Food Proudly Supports the LGTBQ Community Order Online or by Phone Today! TLCPETFOOD.COM | 1•877•328•8400 2 June 2020 / July 2020 theBUZZmag.ca theBUZZmag.ca June 2020 / July 2020 3 Issue #037 The Editor Planning your Muskoka wedding? Make it magical Greetings and Salutations, at our lakeside resort in Ontario. Happy Pride! Although we’re in a time of change and Publisher + Creative Director uncertainty, we still must remain hopeful for a brighter future, Antoine Elhashem and we’re here to offer some uplifting, and positive stories to Editor-in-Chief kick start your summer. Bryen Dunn Art Director Feature one spotlights the incredible work of Brooklyn’s House Mychol Scully of YES collective, an incubator for the creation of awesome parties, cabaret shows, and outrageous events. While their General Manager live events are notorious, they too have had to move into Kim Dobie the digital world, where they’ve been hosting Saturday night Call +1(800)461-0243 or visit MuskokaWeddingVenues.com Sales Representatives interactive dance parties, deep house yoga, drag shows, Carolyn Burtch, Darren Stehle burlesque and dance classes, and their video project, HoY Events Editor TV. Our writer, Raymond Helkio, caught up with HoY to find Sherry Sylvain out what’s up, and he also attended one of their online yoga Counsel classes, which apparently was quite tantalizing.