Publilius Syrus, Maksymy Moralne – Sententiae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Latin Grammar

NEW LATIN GRAMMAR BY CHARLES E. BENNETT Goldwin Smith Professor of Latin in Cornell University Quicquid praecipies, esto brevis, ut cito dicta Percipiant animi dociles teneantque fideles: Omne supervacuum pleno de pectore manat. —HORACE, Ars Poetica. COPYRIGHT, 1895; 1908; 1918 BY CHARLES E. BENNETT PREFACE. The present work is a revision of that published in 1908. No radical alterations have been introduced, although a number of minor changes will be noted. I have added an Introduction on the origin and development of the Latin language, which it is hoped will prove interesting and instructive to the more ambitious pupil. At the end of the book will be found an Index to the Sources of the Illustrative Examples cited in the Syntax. C.E.B. ITHACA, NEW YORK, May 4, 1918 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The present book is a revision of my Latin Grammar originally published in 1895. Wherever greater accuracy or precision of statement seemed possible, I have endeavored to secure this. The rules for syllable division have been changed and made to conform to the prevailing practice of the Romans themselves. In the Perfect Subjunctive Active, the endings -īs, -īmus, -ītis are now marked long. The theory of vowel length before the suffixes -gnus, -gna, -gnum, and also before j, has been discarded. In the Syntax I have recognized a special category of Ablative of Association, and have abandoned the original doctrine as to the force of tenses in the Prohibitive. Apart from the foregoing, only minor and unessential modifications have been introduced. In its main lines the work remains unchanged. -

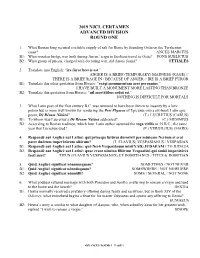

2019 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2019 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. What Roman king secured a reliable supply of salt for Rome by founding Ostia on the Tyrrhenian coast? ANCUS MARCIUS B1: What wooden bridge was built during Ancus’ reign to facilitate travel to Ostia? PONS SUBLICIUS B2: What group of priests, charged with declaring war, did Ancus found? FĒTIĀLĒS 2. Translate into English: “īra fūror brevis est.” ANGER IS A BRIEF (TEMPORARY) MADNESS (RAGE) // THERE IS A BRIEF RAGE IN / BECAUSE OF ANGER // IRE IS A BRIEF FUROR B1: Translate this other quotation from Horace: “exēgī monumentum aere perennius.” I HAVE BUILT A MONUMENT MORE LASTING THAN BRONZE B2: Translate this quotation from Horace: “nīl mortālibus arduī est.” NOTHING IS DIFFICULT FOR MORTALS 3. What Latin poet of the first century B.C. was rumored to have been driven to insanity by a love potion but is more well known for rendering the Peri Physeos of Epicurus into a six-book Latin epic poem, Dē Rērum Nātūrā? (T.) LUCRETIUS (CARUS) B1: To whom was Lucretius’s Dē Rērum Nātūrā addressed? (C.) MEMMIUS B2: According to Roman tradition, which later Latin author assumed the toga virīlis in 55 B.C., the same year that Lucretius died? (P.) VERGIL(IUS) (MARO) 4. Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quī prīnceps futūrus dormīvit per mūsicam Nerōnis et erat pater duōrum imperātōrum aliōrum? (T. FLAVIUS) VESPASIANUS / VESPASIAN B1: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latine: quō Nerō Vespasiānum mīsit?(AD) JUDAEAM / TO JUDAEA B2: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quae erant nōmina fīliōrum Vespasiānī quī ambō imperātōrēs factī sunt? TITUS (FLAVIUS VESPASIANUS) ET DOMITIANUS / TITUS & DOMITIAN 5. -

The Poems of Isabella Whitney: a Critical Edition

THE POEMS OF ISABELLA WHITNEY: A CRITICAL EDITION by MICHAEL DAVID FELKER, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved May 1990 (c) 1990, Michael David Felker ACKNOWLEDGMENT S I would like especially to thank the librarians and staff of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the British Library for their assistance and expertise in helping me trace the ownership of the two volumes of Isabella Whitney's poetry, and for their permission to make the poems of Isabella Whitney available to a larger audience. I would also like to thank the members of my committee. Dr. Kenneth Davis, Dr. Constance Kuriyama, Dr. Walter McDonald, Dr. Ernest Sullivan, and especially Dr. Donald Rude who contributed his knowledge and advice, and who provided constant encouragement throughout the lengthy process of researching and writing this dissertation. To my wife, who helped me collate and proof the texts until she knew them as well as I, I owe my greatest thanks. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE vi BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE viii BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE xxxviii INTRODUCTION Literary Tradition and the Conventions Ixii Prosody cvi NOTE ON EDITORIAL PRINCIPLES cxix THE POEMS The Copy of a Letter 1 [THE PRINTER TO the Reader] 2 I. W. To her vnconstant Louer 3 The admonition by the Auctor 10 [A Loueletter, sent from a faythful Louer] 16 [R W Against the wilfull Inconstancie of his deare Foe E. T. ] 22 A Sweet Nosgay 29 To the worshipfull and right vertuous yong Gentylman, GEORGE MAINWARING Esquier 30 The Auctor to the Reader 32 [T. -

Chaucer's Tale of Melibee As a Proverb Collection

Oral Tradition, 17/2 (2002): 169-207 Ubiquitous Format? What Ubiquitous Format? Chaucer’s Tale of Melibee as a Proverb Collection Betsy Bowden Ut librum aperirem, apertum legerem, lectum memorie commendarem. quia lecta memorie commendata discipulum perficiunt, et perfectus ad magistratus cathedram exaltatur.1 In a sample letter for university students contemplating the job market, John of Garland articulates the formerly obvious idea that an aspiring professor would open and read a book in order to commit it to memory. According to many authorities besides this Englishman in thirteenth-century Paris, literacy represents a pragmatic step in the lifelong process of developing one’s memory. A Chaucerian narrator makes a similar point: “yf that olde bokes were aweye, / Yloren [lost] were of remembraunce the keye.”2 Books as external visual artifacts, as keys to remembrance, could help a pre-modern reader to stock and later to unlock his internal storehouse of knowledge and indeed wisdom.3 Not even the Clerk reads from a book on horseback, though, within the imagined scenario of the Canterbury Tales. Instead, using his listeners’ vernacular language, this university student conveys to the less learned pilgrims a portion of the non-vernacular verbal art lodged within his memory: Petrarch’s Latin tale, transformed orally into Middle English. Geoffrey Chaucer’s major unfinished work, in which the Host of the Tabard Inn urges a tale-telling contest upon “nyne and twenty . sondry 1 “For me to open the book, to read what I opened to, to commit what I read to memory. because committing his reading to memory perfects a student, and the perfected man is promoted to a master’s chair” (John of Garland 1974:62-63). -

Shakespeare's Use of Proverbs for Characterization

SHAKESPEARE'S USE OF PROVERBS FOR CHARACTERIZATION, DRAJyiATIC ACTION, AND TONE IN REPRESENTATIVE COMEDY by EMMETT WAYNE COOK, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1974 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply indebted to Professor Joseph T. McCullen, Jr. for his direction of this dissertation and to the other members of my committee. Professors Warren S. Walker and Kenneth W. Davis, for their helpful criticism. 11 CONTENTS PREFACE 1 CHAPTER ONE: PROVERBS USED FOR CHARACTERIZATION. 12 I. The Falstaffian Figure 13 II. The Clown-Fool 32 III. The Malcontent 43 IV. The Comic Fop 47 V. Other Representative Comic Figures .... 57 CHAPTER TWO: PROVERBS USED IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF DRAMATIC ACTION 64 I. Proverbs Used to Reveal Past Action ... 66 II. Proverbs Used to Foreshadow Aspects of Character Development 73 III. Proverbs Used to Incite Action and Arouse Conflict 77 IV. Proverbs Used to Accentuate a Character's Method of Action 87 V. Proverbs Used to Expose the Immediate Dramatic Situation 98 VI. Proverbs Used to Convey a Sense of Anticipation of Action 110 VII. Proverbs Used as Devices for Sustain ing Comic Interlude 118 VIII. Proverbs Used as Devices for Greeting and Salutation 125 CHAPTER THREE: PROVERBS USED FOR SUSTAINING TONE . 130 CHAPTER FOXJR: CONCLUSION 164 BIBLIOGRAPHY 167 • • • 111 PREFACE One of the curiosities of historical and modern schol arship is the rather engaging matter of defining the obvious or familiar. Defining the common proverb truly illustrates such a statement. -

2013%Yale%Certamen%Invitational% Advanced%Division% Round%1% %

2013%Yale%Certamen%Invitational% Advanced%Division% Round%1% % 1. The Lex Canuleia abolished what prohibition set forth in the 12 Tables? THAT AGAINST PLEBEIAN-PATRICIAN INTERMARRIAGE B1 What was the effect of the Lex Ogulnia? OPENED PRIESTHOOD TO PLEBEIANS B2 During what war did the Romans pass the Lex Oppia, which restricted a woman’s wealth as well as her ability to display her wealth in her dress and other personal adornments? 2ND PUNIC WAR 2. Say in Latin: "Let's go to Athens." EAMUS ATHĒNĀS B1 Say in Latin: "If only I had believed you." UTINAM TIBI CRĒDIDISSEM B2 Say in Latin: "What were we to do?" QUID AGERĒMUS / FACERĒMUS 3. Who became a bird, a tree, and a tigress in rapid succession as she attempted to resist the embrace of Peleus? THETIS B1 Who were the parents of Thetis? NEREUS AND DORIS B2 Whom did Thetis once summon from Tartarus to aid Zeus when Poseidon, Hera, and Athena rebelled against him? (O)BRIAREÜS 4. What fruit did the Romans call malum punicum? POMEGRANATE B1 What fruit did the Romans call malum persicum? PEACH B2 What fruit did the Romans call cerasus? CHERRY 5. Quid Anglicē significat “carcer”? PRISON / STARTING GATE B1 Quid Anglicē significat “cinis”? ASHES / DEATH / RUIN B2 Quid Anglicē significat “carīna”? KEEL / SHIP 6. Make the pronoun hic, haec, hoc agree with the noun form moenia. HAEC 2013%Yale%Certamen%Invitational% Advanced%Division% Round%1% % B1 Now make the pronoun hic, haec, hoc agree with the noun form mōrēs. HĪ / HŌS B2 Make the phrase hī mōrēs ablative singular. -

SENEGA's USE of STOIC THEMES, with an INDEX of IDEAS to BOOKS I-VII of the SPISTULAE MORALES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial F

SENEGA'S USE OF STOIC THEMES, WITH AN INDEX OF IDEAS TO BOOKS I-VII OF THE SPISTULAE MORALES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State U.uiversity By GEORGE ROBERT HOLSINGER, JR., B.S. in Ed., M.A. The Ohio State University 195>2 Approved by Adviser i ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to acknowledge with grateful appreciation the invaluable assistance given in the preparation of this dis sertation by Dr. Kenneth M. Abbott of the Department of Classical Languages, the Ohio State University. I desire also to offer thanks to my wife, Yvonne, for her constant assistance and encouragement. 9S17G8 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Introduction • iii Seneca as Stoic ................................... .. 1 Seneca as a Literary M a n • 7 Seneca's Use of Stoic Themes .......... 13 Index of Ideas ....... 60 English -* Latin Index ••.••.................... 295 Terms in Special Classifications ......... 309 Bibliography ..................... 312 Autobiography ................................ 315 iii INTRODUCTION It should be mentioned at the outset that this dissertation is but the first section of a proposed work which will encompass the entire body of Senecan writing in an Index of Ideas, which proposed work in turn will be directly connected with a detailed study of the influences of Roman Stoicism upon the thought of the writers of the early Christian Church, among them St, Augustine, St, Jerome, and Tertullian. This particular point has not been thoroughly studied -

Preparing for the M.A. Latin Literature Exam Students Should Be Prepared

Preparing for the M.A. Latin Literature Exam Students should be prepared to demonstrate both a broad and eep knowledge of Latin literature on the M.A. Exam. Read widely in the various genres and periods in translations to broaden your repertoire. Know some authors and works welld enough to cite examples and discuss details from more than one perspective. To learn the literary and historical context, read widely in both primary and secondary sources. Primary Read some of each and be able to discuss the following genres and authors: Poetry Prose Drama Rhetoric Plautus Cicero’s Speeches Terence Cicero, Brutus, De re publica Seneca the Younger Seneca the Younger, Consolationes Quintilian Epic Lucretius History Vergil Caesar Ovid, Metamorphoses Sallust Lucan Livy Tacitus Satire Suetonius Horace Juvenal Letters Cicero Lyric/Elegy Pliny the Younger Catullus Horace Novels Propertius Petronius Tibullus Apuleius Ovid Martial MALatinLit16_preparing Secondary The following handbooks are recommended: A Companion to Latin Literature. Edited by S. Harrison. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005. Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Latin. Edited by E. J. Kenney and W. Clausen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. Conte, G. B. Latin Literature. A History. Translated by Joseph B. Solodow. Revised by Don Fowler and Glenn W. Most. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994. (don’t forget the appendices!) Some of the recent translations in the Oxford World Classics series have introductions by leading scholars. The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.) may also be consulted. Format of the Exam The Exam sets two essay questions and 12 identifications. There will be choice in both categories, but the candidate is reminded to demonstrate breadth and depth overall. -

The Humanist Reform of Latin and Latin Teaching

4 The humanist reform of Latin and Latin teaching KRISTIAN JENSEN Despite the many changes which were made during the Renaissance, humanist Latin represented a development of both the forms and the functions of medieval Latin. Latin was the language of the educated and of, if not the ruling, at least the governing classes. Not knowing Latin demonstrated that one did not belong to these social groups. In the Middle Ages, Latin was the international language of secular and ecclesiastical administration, of diplomacy, of liturgy and of the educational institutions where students were prepared for positions in these spheres. Interest in Latin was motivated by practical concerns. Official correspondence in Latin was the most important task of those engaged in church and secular administration. The ars dictaminis, of art of letter-writing, had been a central feature of late medieval education in Italy, but less so north of the Alps, where university education was directed towards theological rather than legal training. In post-medieval Italy, Latin retained all these functions, and the art of writing letters and composing orations remained important aspects of Latin education. In no area were prestige and presentation of greater importance than in matters of state. International affairs were transacted in Latin through the exchange of letters and through orations delivered by envoys. Humanist Latin emerged in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries in Italy among men in the highest ranks of ecclesiastical or civil administration. Chancellors of Florence, such as Leonardo Bruni and Poggio Bracciolini, both of whom had also served as secretaries to the pope, were prominent exponents. -

Complete Issue

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 17 October 2002 Number 2 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley Michael Barnes Heather Maring Associate Editor John Zemke Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. Indiana University 2611 E. 10th St. Bloomington, IN 47408-2603 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright © 2002 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations. -

Las Sententiae De Publilio Siro Seleccionadas Por Erasmo Y Su Influencia En Los Florilegios De G

ARTÍCULOS Cuadernos de Filología Clásica. Estudios Latinos ISSN: 1131-9062 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/CFCL.60934 Las Sententiae de Publilio Siro seleccionadas por Erasmo y su influencia en los florilegios de G. Maior y A. Rodrigues de Évora1 Francisco Bravo de Laguna Romero2; Gregorio Rodríguez Herrera3 Recibido: 6 de marzo de 2017 / Aceptado: 12 de enero de 2018 Resumen. La edición de Erasmo de las Sententiae de Publilio Siro (1514) marca un antes y un después en la fortuna literaria del mimo romano y su obra. Este trabajo estudia la vinculación de las sentencias de Publilio Siro, seleccionadas por Erasmo, con las Sententiae ueterum poetarum (1534) de G. Maior y las Sententiae et Exempla ex probatissimis scriptoribus collecta (1557) de A. Rodrigues de Évora. A partir del análisis de estas obras ofrecemos una clasificación temática de la selección erasmiana y demostramos el grado de seguimiento de la edición erasmiana por parte de los compiladores. Palabras Clave: Publilio Siro; sententiae; florilegios; Erasmo. [en] Erasmus’ selection of Publilio Siro’s Sententiae and its influence on the florilegia of G. Maior and A. Rodrigues de Évora Abstract. Erasmus’ edition of Publilio Siro’s Sententiae (1514) constitutes a landmark in the literary fortune of this Roman mime and his work. This article studies the relationship between the sententiae of Publilio Siro selected by Erasmus and the Sententiae ueterum poetarum (1534) by G. Maior and the Sententiae et Exempla ex probatissimis scriptoribus collecta (1557) by A. Rodrigues de Évora. The analysis of these works will allow to offer a thematic classification of the Erasmian selection and to show to what extent these compilers have followed the Erasmian edition.