Paper Machines: About Cards & Catalogs, 1548 – 1929

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ass Spielkarten

Werbemittelkatalog www.werbespielkarten.com Spielkarten können das ASS im Ärmel sein ... Spielkarten als Werbemittel bleiben in Erinnerung – als kommunikatives Spielzeug werden sie entspannt in der Freizeit genutzt und eignen sich daher hervorragend als Werbe- und Informationsträger. Die Mischung macht‘s – ein beliebtes Spiel, qualitativ hochwertige Karten und Ihre Botschaft – eine vielversprechende Kombination! Inhalt Inhalt ........................................................................ 2 Unsere grüne Mission ............................... 2 Wo wird welches Blatt gespielt? ..... 3 Rückseiten ........................................................... 3 Brandneu bei ASS Altenburger ........ 4 Standardformate ........................................... 5 Kinderspiele ........................................................ 6 Verpackungen .................................................. 7 Quiz & Memo ................................................... 8 Puzzles & Würfelbecher ....................... 10 Komplettspiele .............................................. 11 Ideen ...................................................................... 12 Referenzen ....................................................... 14 Unsere grüne Mission Weil wir Kunden und Umwelt gleichermaßen verpflichtet sind ASS Altenburger will mehr erreichen, als nur seine geschäftlichen Ziele. Als Teil eines globalen Unternehmens sind wir davon überzeugt, eine gesellschaftliche Verantwortung für Erde, Umwelt und Menschen zu haben. Wir entscheiden uns bewusst -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

PARTIAL LIST CF RFFLRENCF WCRES on PULP AN® IDAIDLR Il

CULTURE ROO M PARTIAL LIST CF RFFLRENCF WCRES ON PULP AN® IDAIDLR Revised May 1959 No. 564 L ! .1111.1 11:1:11.111111111 ~— .1111111111 1' Il iri IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII . UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTUR E FOREST PRODUCTS LABORATOR Y FOREST SERVIC E MADISON 5, WISCONSIN In Cooperation with the University of Wisconsin A PARTIAL LIST OF REFERENCE WORKS ON PULP AND PAPE R General information regarding pulp and paper making can often be ob- tained by consulting general encyclopedias and technical handbooks . These may be found in technical and general libraries, where it ma y also be possible to secure some of the following references specificall y relating to this subject. However, if any of them are especially de - sired and cannot be obtained otherwise, they may be bought from the publishers or through the larger book dealers . American paper and pulp association. The dictionary of paper ; including pulps, boards, paper properties, and related papermaking terms . 2d ed. The Association, 1951 . 393 p . $6 .50 . American pulp and paper mill superintendents association. Yearbook and program . 337 S . LaSalle St. , Chicago 4, Ill . The Association. Issued annually to members . American Society for Testing Materials . ASTM standards on paper and pape r products ; prepared by Corn . D-6 on paper and paper products in Part 6 . Philadelphia, The Society . 1958. 500 p . on paper and paper product s $10 .00 . Bettendorf, H . J. Paperboard and paperboard containers : a history. Rev. version . Chicago, Board Products Publishing Co . , 1946 . 135 p. $6 . British paper and board makers association . Tech. section. Proceeding s 1921 . St. -

Chapter 48 Paper and Paperboard; Articles of Paper Pulp, of Paper Or Of

Section X Chapter 48 Chapter 48 Paper and paperboard; articles of paper pulp, of paper or of paperboard Notes. 1.- For the purposes of this Chapter, except where the context otherwise requires, a reference to “paper” includes references to paperboard (irrespective of thickness or weight per m2). 2.- This Chapter does not cover: (a) Articles of Chapter 30; (b) Stamping foils of heading 32.12; I Perfumed papers or papers impregnated or coated with cosmetics (Chapter 33); (d) Paper or cellulose wadding impregnated, coated or covered with soap or detergent (heading 34.01), or with polishes, creams or similar preparations (heading 34.05); (e) Sensitised paper or paperboard of headings 37.01 to 37.04; (f) Paper impregnated with diagnostic or laboratory reagents (heading 38.22); (g) Paper-reinforced stratified sheeting of plastics, or one layer of paper or paperboard coated or covered with a layer of plastics, the latter constituting more than half the total thickness, or articles of such materials, other than wall coverings of heading 48.14 (Chapter 39); (h) Articles of heading 42.02 (for example, travel goods); (ij) Articles of Chapter 46 (manufactures of plaiting material); (k) Paper yarn or textile articles of paper yarn (Section XI); (l) Articles of Chapter 64 or Chapter 65; (m) Abrasive paper or paperboard (heading 68.05) or paper- or paperboard-backed mica (heading 68.14) (paper and paperboard coated with mica powder are, however, to be classified in this Chapter); (n) Metal foil backed with paper or paperboard (generally Section XIV or XV); (o) Articles of heading 92.09; or (p) Articles of Chapter 95 (for example, toys, games, sports requisites) or Chapter 96 (for example, buttons). -

List of Compositions and Arrangements

Eduard de Boer: List of compositions and arrangements 1 2 List of Compositions and Arrangements I. Compositions page: — Compositions for the stage 5 Operas 5 Ballets 6 Other music for the theatre 7 — Compositions for or with symphony or chamber orchestra 8 for symphony or chamber orchestra 8 for solo instrument(s) and symphony or chamber orchestra 3 for solo voice and symphony orchestra : see: Compositions for solo voice(s) and accompaniment → for solo voice and symphony orchestra 45 for chorus and symphony or chamber orchestra : see: Choral music (with or without solo voice(s)) → for chorus and symphony or chamber orchestra 52 — Compositions for or with string orchestra 11 for string orchestra 11 for solo instrument(s) and string orchestra 13 for chorus and string orchestra : see: Choral music (with or without solo voice(s)) → for chorus and string orchestra 55 — Compositions for or with wind orchestra, fanfare orchestra or brass band 15 for wind orchestra 15 for solo instrument(s) and wind orchestra 19 for solo voices and wind orchestra : see: Compositions for solo voice(s) and accompaniment → for solo voices and wind orchestra 19 for chorus and wind orchestra : see: Choral music (with or without solo voice(s)) → for chorus and wind orchestra : 19 for fanfare orchestra 22 for solo instrument and fanfare orchestra 24 for chorus and fanfare orchestra : see: Choral music (with or without solo voice(s)) → for chorus and fanfare orchestra 56 for brass band 25 for solo instrument and brass band 25 — Compositions for or with accordion orchestra -

Spielanleitung Holzspielesammlung (D).Qxd 15.09.2009 10:44 Uhr Seite 2

Holzspielesammlung (D).qxd 15.09.2009 10:44 Uhr Seite 1 D Spielanleitung Holzspielesammlung (D).qxd 15.09.2009 10:44 Uhr Seite 2 © Philos GmbH & Co. KG Friedrich-List-Str. 65 33100 Paderborn Germany www.philosspiele.de Holzspielesammlung (D).qxd 15.09.2009 10:44 Uhr Seite 3 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Spielpläne Brettspiele 1 Spielplan Immer mit der Ruhe – Mühle 1 Spielplan Barricade – Halma Schach . 18 1 Spielplan Backgammon – Schach / Dame Häuptling und Krieger . 20 Double-Schach . 20 K.-o.-Schach . 20 Spielmaterial Schlagschach . 20 50 Spielkegel (Holz): 15 blaue, 15 rote, Positionsschach . 20 15 grüne, 5 gelbe Dame . 20 41 Mikadostäbchen (Holz) Polnische Dame . 21 32 Schachfiguren (Holz) Französische Dame . 21 30 Spielsteine (Holz) Eckdame . 21 28 Dominosteine (Holz) Schlagdame . 22 20 Holzstäbchen Blockade . 22 11 Barricade-Sperrsteine (Holz) Contract-Checkers . 22 4 Würfel: 2 rote, 2 weiße Wolf und Schafe . 22 1 Dopplerwürfel Rösselsprung . 22 1 Würfelbecher Mühle . 23 2 Spielkarten-Sets (französisches Blatt) Die Lasker’sche Mühle . 24 Die Springermühle . 24 Würfelmühle . 24 Eckmühle . 25 Treibjagd . 25 Hüpfmühle . 25 Kreuzmühle . 25 Würfel-Brettspiele Halma . 26 Halma Solo . 26 Immer mit der Ruhe . 5 Das Partnerspiel . 5 ✦✦✦ Parken . 6 Crazy India . 6 Knobelspiele (Würfel) Frank und Furter . 6 Orbite . 6 Schaukel . 27 Ausreißer . 7 Nackter Spatz . 27 Barricade . 7 Die böse 3 . 27 Backgammon . 8 Sechzehn-tot . 27 Tric-Trac . 14 Stumme Jule . 28 Puff . 16 6er-Spiel . 28 Catch Me . 16 Zeppelin . 28 Chouette . 17 Hohe Hausnummer . 29 Jacquet . 17 101, aber keine Eins . 29 Doppelsteine . 17 Die lustige 7 . 29 Himmel und Hölle . 29 ✦✦✦ Elf hoch . -

4Th & 5Th Grade 6Th Grade

2019-2020 Middle School Supply List Note: It is important for students to have the supplies listed by Friday, August 30, 2019. We will spend the first few days getting students organized for the school year. This list may not be all-inclusive and other supplies may be needed during the school year (poster board for projects, additional loose leaf paper, extra pencils, etc.) If you have any questions about the supply list, please call Karen Snyder, Middle School Principal, at 727.7266. All textbooks must be covered with the book covers of your choice. Marshall School will provide an academic planner for each Middle School student. 4th & 5th Grade 4th & 5th Grade Music & Art 1 Trapper Keeper with dividers for 1 ½” white 3-ring binder with plastic subject materials cover, to be kept in classroom 1 spiral notebook 1 8.5”x11” or 9”x12” sketchbook 1 3-subject notebook for math 1 3-ring mesh pencil holder 4 1-subject notebooks 4 Mead Composition 100-sheet, th 200-page, wide-ruled black notebooks 6 Grade 2 packs of lined, loose leaf, college-ruled paper 1 Trapper Keeper with accordion file 7 pocket folders 2 Mead Composition 100-sheet, 2 boxes of #2 pencils OR mechanical 200-page, wide-ruled black notebooks pencils with extra lead & erasers 1 3-subject notebook for math 1 box of 36 or more colored pencils 2 packages of loose leaf paper 1 12 pack of markers 1 pack of graph paper 1 zipper pouch or pencil case 3 boxes of #2 pencils OR 1 pair of scissors mechanical pencils with extra lead 1 set of ear buds for iPad 1 box of 36 or more colored pencils -

Spielanleitung

Spielanleitung DE Philos GmbH & Co. KG Friedrich-List-Str. 65 33100 Paderborn Germany [email protected] 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Spielpläne Brettspiele 1 Spielplan Immer mit der Ruhe – Mühle 1 Spielplan Barricade – Halma Schach . 18 1 Spielplan Backgammon – Schach / Häuptling und Krieger ........... 20 Dame Double-Schach ................ 20 K.-o.-Schach .................. 20 Schlagschach.................. 20 Spielmaterial Positionsschach................ 20 50 Spielkegel (Holz): 15 blaue, 15 rote, Dame ......................... 20 15 grüne, 5 gelbe Polnische Dame................ 21 41 Mikadostäbchen (Holz) Französische Dame ............. 21 32 Schachfiguren (Holz) Eckdame ..................... 21 30 Spielsteine (Holz) Schlagdame................... 22 28 Dominosteine (Holz) Blockade ..................... 22 20 Holzstäbchen Contract-Checkers .............. 22 11 Barricade-Sperrsteine (Holz) Wolf und Schafe ............... 22 4 Würfel: 2 natur, 2 weiße Rösselsprung.................. 22 1 Dopplerwürfel Mühle . 23 1 Würfelbecher Die Lasker’sche Mühle........... 24 2 Spielkarten-Sets (französisches Blatt) Die Springermühle .............. 24 Würfelmühle................... 24 Eckmühle ..................... 25 Treibjagd ..................... 25 Hüpfmühle .................... 25 Kreuzmühle . 25 Halma ......................... 26 Würfel-Brettspiele Halma Solo ................... 26 Würfelspiel ..................... 5 www Das Partnerspiel ............... 5 Parken ....................... 6 Knobelspiele (Würfel) Crazy India ................... 6 Frank -

Chapter 48 Paper and Paperboard; Articles of Paper Pulp, of Paper Or Of

Chapter 48 Paper and paperboard; articles of paper pulp, of paper or of paperboard Notes. 1.- For the purposes of this Chapter, except where the context otherwise requires, a reference to “paper” includes references to paperboard (irrespective of thickness or weight per m²). 2.- This Chapter does not cover : (a) Articles of Chapter 30; (b) Stamping foils of heading 32.12; (c) Perfumed papers or papers impregnated or coated with cosmetics (Chapter 33); (d) Paper or cellulose wadding impregnated, coated or covered with soap or detergent (heading 34.01), or with polishes, creams or similar preparations (heading 34.05); (e) Sensitised paper or paperboard of headings 37.01 to 37.04; (f) Paper impregnated with diagnostic or laboratory reagents (heading 38.22); (g) Paper-reinforced stratified sheeting of plastics, or one layer of paper or paperboard coated or covered with a layer of plastics, the latter constituting more than half the total thickness, or articles of such materials, other than wall coverings of heading 48.14 (Chapter 39); (h) Articles of heading 42.02 (for example, travel goods); (ij) Articles of Chapter 46 (manufactures of plaiting material); (k) Paper yarn or textile articles of paper yarn (Section XI); (l) Articles of Chapter 64 or Chapter 65; (m) Abrasive paper or paperboard (heading 68.05) or paper- or paperboard-backed mica (heading 68.14) (paper and paperboard coated with mica powder are, however, to be classified in this Chapter); (n) Metal foil backed with paper or paperboard (generally Section XIV or XV); (o) Articles of heading 92.09; or (p) Articles of Chapter 95 (for example, toys, games, sports requisites) or Chapter 96 (for example, buttons). -

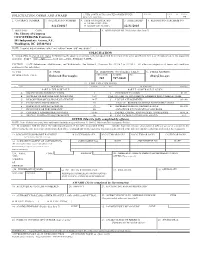

FEDLINK Preservation Basic Services Ordering

SOLICITATION, OFFER AND AWARD 1. THIS CONTRACT IS A RATED ORDER UNDER RATING PAGE OF PAGES DPAS (15 CFR 700) 1 115 2. CONTRACT NUMBER 3. SOLICITATION NUMBER 4. TYPE OF SOLICITATION 5. DATE ISSUED 6. REQUISITION/PURCHASE NO. G SEALED BID (IFB) S-LC04017 G NEGOTIATED (RFP) 12/31/2003 7. ISSUED BY CODE 8. ADDRESS OFFER TO (If other than Item 7) The Library of Congress OCGM/FEDLINK Contracts 101 Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC 20540-9414 NOTE: In sealed bid solicitations “offer” and “offeror” mean “bid” and “bidder” SOLICITATION 9. Sealed offers in original and copies for furnishing the supplies or services in the Schedu.le will be received at the place specified in Item 8, or if handcarried, in the depository located in Item 7 until __2pm______ local time __Tues., February 4, 2004_. CAUTION -- LATE Submissions, Modifications, and Withdrawals: See Section L, Provision No. 52.214-7 or 52.215-1. All offers are subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation. 10. FOR A. NAME B. TELEPHONE (NO COLLECT CALLS) C. E-MAIL ADDRESS INFORMATION CALL: Deborah Burroughs AREA CODE NUMBER EXT. [email protected] 202 707-0460 11. TABLE OF CONTENTS ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) PART I - THE SCHEDULE PART II - CONTRACT CLAUSES A SOLICITATION/CONTRACT FORM 1 I CONTRACT CLAUSES 91-97 B SUPPLIES OR SERVICES AND PRICE/COST 3-23 PART III - LIST OF DOCUMENTS, EXHIBITS AND OTHER ATTACH. C DESCRIPTION/SPECS./WORK STATEMENT 24-77 J LIST OF ATTACHMENTS 98-100 D PACKAGING AND MARKING 78 PART IV - REPRESENTATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS E INSPECTION AND ACCEPTANCE 79 K REPRESENTATIONS, CERTIFICATIONS 101-108 F DELIVERIES OR PERFORMANCE 80 AND OTHER STATEMENTS OF OFFERORS G CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION DATA 81-89 L INSTRS., CONDS., AND NOTICES TO OFFERORS 109-114 H SPECIAL CONTRACT REQUIREMENTS 90 M EVALUATION FACTORS FOR AWARD 115 OFFER (Must be fully completed by offeror) NOTE: Item 12 does not apply if the solicitation includes the provisions at 52.214-16, Minimum Bid Acceptance Period. -

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT for DISTRIBUTION References Afanas’Ev, Aleksandr

Contents Foreword Donald Haase vii Introduction: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Teaching Folklore and Fairy Tales in Higher Education Christa C. Jones and Claudia Schwabe 3 Part I Fantastic ENvIRONMENTS: MAPPING Fairy TALES, FOLKLORE, AND THE OTHERWORLD 1 Fairy Tales, Myth, and Fantasy Christina Phillips Mattson and Maria Tatar 21 2 Teaching Fairy Tales in Folklore Classes Lisa Gabbert 35 3 At the Bottom of a Well: Teaching the Otherworld as a Folktale EnvironmentCOPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOTJuliette FOR Wood DISTRIBUTION 48 Part II SOCIOPOLITICAL AND CULTURAL APPROACHES TO TEACHING CANONICAL Fairy TALES 4 The Fairy-Tale Forest as Memory Site: Romantic Imagination, Cultural Construction, and a Hybrid Approach to Teaching the Grimms’ Fairy Tales and the Environment Doris McGonagill 63 5 Grimms’ Fairy Tales in a Political Context: Teaching East German Fairy-Tale Films Claudia Schwabe 79 vi Contents 6 Teaching Charles Perrault’s Histoires ou contes du temps passé in the Literary and Historical Context of the Sun King’s Reign Christa C. Jones 99 7 Lessons from Shahrazad: Teaching about Cultural Dialogism Anissa Talahite-Moodley 113 Part III DECODING Fairy-TALES SEMANTICS: ANALYSES OF TRANSLATION ISSUES, LINGUISTICS, AND SYMBOLISMS 8 The Significance of Translation Christine A. Jones 133 9 Giambattista Basile’s The Tale of Tales in the Hands of the Brothers Grimm Armando Maggi 147 10 Teaching Hans Christian Andersen’s Tales: A Linguistic Approach Cyrille François 159 11 Teaching Symbolism in “Little Red Riding Hood” Francisco Vaz da Silva 172 Part Iv CLASSICAL TALES THROUGH THE GENDERED LENS: CINEMATIC ADAPTATIONS IN THE TRADITIONAL CLASSROOM AND ONLINE 12 Binary Outlaws:COPYRIGHTED Queering the Classical MATERIAL Tale in François Ozon’s Criminal LoversNOT and Catherine FOR DISTRIBUTIONBreillat’s The Sleeping Beauty Anne E. -

TAPPI Standards: Regulations and Style Guidelines

TAPPI Standards: Regulations and Style Guidelines REVISED January 2018 1 Preface This manual contains the TAPPI regulations and style guidelines for TAPPI Standards. The regulations and guidelines are developed and approved by the Quality and Standards Management Committee with the advice and consent of the TAPPI Board of Directors. NOTE: Throughout this manual, “Standards” used alone as a noun refers to ALL categories of Standards. For specific types, the word “Standard” is used as an adjective, e.g., “Standard Test Method,” “Standard Specification,” “Standard Glossary,” or “Standard Guideline.” If you are a Working Group Chairman preparing a Standard or reviewing an existing Standard, you will find the following important information in this manual: • How to write a Standard Test Method using proper terminology and format (Section 7) • How to write TAPPI Standard Specifications, Glossaries, and Guidelines using proper terminology and format (Section 8) • What requirements exist for precision statements in Official and Provisional Test Methods (Sections 4.1.1.1, 4.1.1.2, 6.4.5, 7.4.17). • Use of a checklist to make sure that all required sections have been included in a Standard draft (Appendix 4). • How Working Group Chairman, Working Groups, and Standard-Specific Interest Groups fit into the process of preparing a Standard (Section 6.3, 6.4.1, 6.4.2, 6.4.3, 6.4.4, 6.4.6, 6.4.7). • How the balloting process works (Sections 6.4.6, 6.4.7, 6.4.8, 6.4.9) • How to resolve comments and negative votes (Sections 9.5, 9.6, 9.7) NOTE: This document covers only the regulations for TAPPI Standards, which may include Test Methods or other types of Standards as defined in these regulations.