Freedmen's Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downtown Development Project List

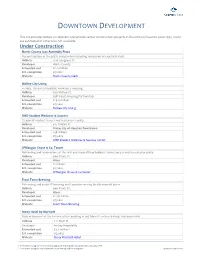

DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT This list provides details on all public and private sector construction projects in Downtown Houston since 1995. Costs are estimated or otherwise not available. Under Construction Harris County Jury Assembly Plaza Reconstruction of the plaza and pavilion including relocation of electrical vault. Address 1210 Congress St. Developer Harris County Estimated cost $11.3 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Harris County Clerk McKee City Living 4‐story, 120‐unit affordable‐workforce housing. Address 626 McKee St. Developer Gulf Coast Housing Partnership Estimated cost $29.9 million Est. completion 4Q 2021 Website McKee City Living UHD Student Wellness & Success 72,000 SF student fitness and recreation facility. Address 315 N Main St. Developer University of Houston Downtown Estimated cost $38 million Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website UHD Student Wellness & Success Center JPMorgan Chase & Co. Tower Reframing and renovations of the first and second floor lobbies, tunnel access and the exterior plaza. Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website JPMorgan Chase & Co Tower Frost Town Brewing Reframing and 9,100 SF brewing and taproom serving locally inspired beers Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2.58 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Frost Town Brewing Moxy Hotel by Marriott Redevelopment of the historic office building at 412 Main St. into a 13‐story, 119‐room hotel. Address 412 Main St. Developer InnJoy Hospitality Estimated cost $4.4 million P Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website Moxy Marriott Hotel V = Estimated using the Harris County Appriasal Distict public valuation data, January 2019 P = Estimated using the City of Houston's permitting and licensing data Updated 07/01/2021 Harris County Criminal Justice Center Improvement and flood damage mitigation of the basement and first floor. -

Center for Public History

Volume 8 • Number 2 • spriNg 2011 CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY Oil and the Soul of Houston ast fall the Jung Center They measured success not in oil wells discovered, but in L sponsored a series of lectures the dignity of jobs well done, the strength of their families, and called “Energy and the Soul of the high school and even college graduations of their children. Houston.” My friend Beth Rob- They did not, of course, create philanthropic foundations, but ertson persuaded me that I had they did support their churches, unions, fraternal organiza- tions, and above all, their local schools. They contributed their something to say about energy, if own time and energies to the sort of things that built sturdy not Houston’s soul. We agreed to communities. As a boy, the ones that mattered most to me share the stage. were the great youth-league baseball fields our dads built and She reflected on the life of maintained. With their sweat they changed vacant lots into her grandfather, the wildcatter fields of dreams, where they coached us in the nuances of a Hugh Roy Cullen. I followed with thoughts about the life game they loved and in the work ethic needed later in life to of my father, petrochemical plant worker Woodrow Wilson move a step beyond the refineries. Pratt. Together we speculated on how our region’s soul—or My family was part of the mass migration to the facto- at least its spirit—had been shaped by its famous wildcat- ries on the Gulf Coast from East Texas, South Louisiana, ters’ quest for oil and the quest for upward mobility by the the Valley, northern Mexico, and other places too numerous hundreds of thousands of anonymous workers who migrat- to name. -

Houstonhouston

RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Texas A&M University July 2001 © 2001, Real Estate Center. All rights reserved. RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Contents 2 Note Population 6 Employment 9 Job Market 10 Major Industries 11 Business Climate 13 Public Facilities 14 Transportation and Infrastructure Issues 16 Urban Growth Patterns Map 1. Growth Areas Education 18 Housing 23 Multifamily 25 Map 2. Multifamily Building Permits 26 Manufactured Housing Seniors Housing 27 Retail Market 29 Map 3. Retail Building Permits 30 Office Market Map 4. Office Building Permits 33 Industrial Market Map 5. Industrial Building Permits 35 Conclusion RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Aldine Jersey Village US Hwy 59 US Hwy 290 Interstate 45 Sheldon US Hwy 90 Spring Valley Channelview Interstate 10 Piney Point Village Houston Galena Park Bellaire US Hwy 59 Deer Park Loop 610 Pasadena US Hwy 90 Stafford Sugar Land Beltway 8 Brookside Village Area Cities and Towns Counties Land Area of Houston MSA Baytown La Porte Chambers 5,995 square miles Bellaire Missouri City Fort Bend Conroe Pasadena Harris Population Density (2000) Liberty Deer Park Richmond 697 people per square mile Galena Park Rosenberg Montgomery Houston Stafford Waller Humble Sugar Land Katy West University Place ouston, a vibrant metropolitan City Business Journals. The city had a growing rapidly. In 2000, Houston was community, is Texas’ largest population of 44,633 in 1900, growing ranked the most popular U.S. city for Hcity. Houston was the fastest to almost two million in 2000. More employee relocations according to a growing city in the United States in the than four million people live in the study by Cendant Mobility. -

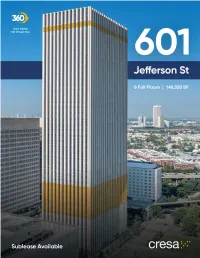

Click Above for Virtual Tour Sublease 601 Jefferson St

Click Above For Virtual Tour Sublease 601 Jefferson St Long-Term Sublease With the remaining term running through June 2030, enjoy peace of mind and long-term savings by locking in below market rents for years to come. Plug & Play Opportunity All floors are fully furnished and ready for occupancy, including Haworth cubicles and office furniture, as well as completely outfitted conference and break rooms. Up To Nearly 150,000 Total SF Available Great Panoramic Views of Downtown DIRTT Walls Quickly tailor your space to your business’ needs Available For Immediate Occupancy by reconfiguring the installed DIRTT Wall offices and conference rooms. Contact Broker For Rate Information For More Information Gary Lawless | 713.491.6307 | [email protected] Samuel Heiber | 202.783.3889 | [email protected] Sublease At-A-Glance Jefferson Towers 6 360+ At Cullen Center Floors Available Building Conference Center Capacity Tunnel Connectivity 88 Enjoy access via skywalk to 1600 Smith St to Houston‘s famed downtown tunnel system offering a wide range of (Very Walkable) retail and dining options all while remaining under protection Walk Score from any inclement weather on the surface level. On-site food court, Frost Bank, Amazon Locker and full-service post office. 1.50/1,000 Thru June 2030 Parking Ratio 25,000 SF Approximate Typical Floor Plate Long-term sublease opportunity 150K SF Building Security Up to nearly 150,000 SF available in total, A robust on-site with more than 123,000 SF contiguous. Great Access security system, including key card 601 Jefferson provides convenient access in and elevators, helps out of downtown via I-10, I-45 and Hwy 59, as well as manage and control Click the icon to the right to get a by Metro‘s bus and light rail transit services. -

Fourteenth Court of Appeals Christopher Prine, Clerk KEN WISE 301 Fannin, Suite 245 Houston, Texas 77002

Justices Chief Justice WILLIAM J. BOYCE KEM THOMPSON FROST TRACY CHRISTOPHER MARTHA HILL JAMISON Clerk SHARON MCCALLY CHRISTOPHER A. PRINE J. BRETT BUSBY PHONE 713-274-2800 JOHN DONOVAN MARC W. BROWN Fourteenth Court of Appeals Christopher Prine, Clerk KEN WISE 301 Fannin, Suite 245 Houston, Texas 77002 January 8, 2016 RE: Destruction of civil case records. Dear District and County Clerks: Beginning April 8, 2016, , the Fourteenth Court of Appeals will begin destruction of records in civil cases that have been finally disposed of and stored for at least six years. See Tex. Gov’t Code Ann. § 51.204(d). Prior to destruction, records requested by a district or county clerk, in accordance with records retention schedules for records of district and county clerks, may be returned to their respective offices. See Tex. Gov’t Code Ann. § 51.204(d) (1). Additionally, records of the appellate court determined to be archival state records will be forwarded to the Texas State Library and Archives Commission for preservation. The following criteria may be considered when identifying archival state records: (1) any landmark legal opinion; (2) any case with a high degree of inherent legal interest, including a case in which the Texas Supreme Court granted an application for petition for review; (3) any case that involved significant people or events; (4) any case that received a high degree of media attention; or (5) records that, in the opinion of the Clerk or other person designated by the Court, contain highly concentrated, unique, and valuable information unlikely to be found in any other source available to researchers. -

Office Market

Q4 2020 | HOUSTON OFFICE MARKET Office Market Sees Continued Fallout Through Year’s End Pandemic, Oil Collapse Lead to Worst Year on Record for Market OVERVIEW ANNUAL TRENDLINES 2020 the Year of the Pandemic The Houston metro office market saw its most challenging year on record as the 5-YEAR TREND global pandemic and collapse in the energy sector led to negative absorption of JOB GROWTH 6.4 million SF over the year. Despite an uptick in leasing activity at year’s end, the fourth quarter saw negative absorption of 1.0 million SF. Impacts to the market -5.0k jobs were felt beyond negative absorption, as sublease supply increased by 934k Year-over-Year Office Employment* SF over the fourth quarter, ending the year at 6.8 million SF available across the metro. The uptick in sublease supply was fueled by the energy sector as Schlum- berger listed over 400k SF across multiple locations, while Maverick Natural ABSORPTION Absorption Resources, TechnipFMC, and McDermott all added sublease listings with term (1.0M) sf in high quality product. With absorption in the red and an increase in sublease 2020 Q4 absorption supply, both vacancy and availability saw upticks, ending the year at new highs of for all classes of space 19.5% and 25.8%, respectively. The market continues to be reshaped by the pandemic and outlook of economic DIRECT VACANCY uncertainty over the near term. As such, leasing activity has been heavily weighted Direct Vacant Available % to short term renewals and blend and extend activity. New leasing has seen much 19.4 Increased 40 bps more of a focus on value over the lure of new construction that dominated the over the quarter decade. -

Tenant Handbook Should Answer Many of the Immediate Questions You May Have About Property Regulations, Policies, and Operating Procedures

INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 WELCOME .................................................................................................................... 3 ABOUT BROOKFIELD ...................................................................................................... 3 ABOUT JEFFERSON TOWERS ......................................................................................... 3 OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS ............................................................................................ 4 MOBILE PROPERTY ....................................................................................................... 4 SEARCH ....................................................................................................................... 5 LEASING .............................................................................................................. 5 LEASING CENTER .......................................................................................................... 5 OPERATIONS ...................................................................................................... 6 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT OFFICE .................................................................................. 6 LEASING CENTER .......................................................................................................... 6 BUILDING HOLIDAYS ..................................................................................................... -

Two Downtown Towers to Undergo Renovations, Rebranding

FOR THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF [email protected] From the Houston Business Journal: http://www.bizjournals.com/houston/news/2016/04/14/two- downtowntowers-to-undergo-renovations.html Two downtown towers to undergo renovations, rebranding Apr 14, 2016, 12:36pm CDT Two downtown towers with rich histories will soon undergo a facelift and rebranding. 708 Main and 712 Main, which is formerly known as the Gulf Oil Building, will be rebranded and joined as The Jones on Main by Houston-based Midway Cos. and Houston-based COURTESY MIDWAY COS Lionstone Investments. The new name pays homage to Jesse H. Jones, who commissioned 712 Main in 1929. Proposed renovations include connecting the two buildings at the ground level via a joint common space and adding classically inspired interior amenities throughout the space. Plans also call for a new restaurant, and space for retail with sidewalk patios along Main Street and Rusk Street. Renovations will kick off in June and should be complete in early 2017. Financial information wasn't made available. "We have a real interest in the success of downtown," said Jonathan Brinsden, CEO of Midway Cos. "We have a number of relationships with Lionstone and this was an opportunity to work with them again." A common area dubbed Currency Lounge will be available to tenants and guests for meetings and social events. The common area will also feature some original fresco paintings detailing Texas history. Colvill Office Properties will handle office leasing. The architect and general contractor were not immediately available. Lionstone bought 712 Main from New York-based Brookfield Asset Management Inc. -

Quarterly Market Report APRIL 2017

HOUSTON OFFICE | Q1 2017 Quarterly Market Report APRIL 2017 Supply & Demand Total Net Absorption (SF) Total Vacant (%) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2.5 22 2.0 21 Office Market Millions 1.5 20 Have we reached the bottom of the office market 1.0 19 in Houston? While many seem to be in agreement that the worst is now behind us, the city is still very 0.5 18 much in an office market slump. Houston’s overall 0.0 17 vacancy rate rose to 20.0% in Q1 2017, an increase -0.5 16 of 100 basis points quarter-over-quarter and 260 -1.0 15 basis points year-over-year. Net absorption stood at -1.5 14 negative 778,758 sq. ft. as of the quarter’s end— on the heels of the more than 1.4 million sq. ft. of -2.0 13 negative absorption for full-year 2016. In addition, -2.5 12 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 both Houston citywide overall rent and leasing 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 activity are down from last quarter, as well as from Q1 2016. However, despite some market sluggishness, available sublease space is down 3.5%, and the Market Indicators amount of space in the construction pipeline has Current Prior Quarter Year Ago declined by 40.0%, quarter–over-quarter. Q1 2017 Q4 2016 Q1 2016 Net Absorption (sq. ft.) Total -778,758 -757,9 54 -198,686 Houston Economy Direct -936,272 -625,127 -453,852 The Houston metro area reported 125,005 new Sublease 157,514 -132,827 255,166 residents from July 1, 2015 to July 1, 2016, and Houston ranks fifth in the 10 most populous metro Leasing Activity (sq. -

Downtown Houston

C i t e 3 2 1 9 9 5 32 DOWNTOWN 1865-1890 1890-1920 International & Great Northern Railway At the foot of Mam Street, extending Main Street is the axis of Houston, The Freight Depot at Commerce and up to Commerce Avenue and stretching center of downtown moves three Caroline and of Union Station at between Milam on the west and blocks south, Irom Main and Congress Crawford and Prairie destabilizes the Caroline on the east, is the wharf, to Main and Texas. The fool of Mam established Second and Third Ward warehouse, and wholesale district. Street remains the public wharf until neighborhoods just east of downtown, Railroad development keeps to the construction ol the Houston Ship identifying them as eligible for absorp- north side of Buffalo Bayou and east of Channel; completion of the Mam Street tion into the expanded commercial downtown. Therefore, railroad tracks Viaduct, spanning Buffalo Bayou above district. Milam Street emerges as the and the development associated with the old waterfront, opens downtown to African-American mam street, stretch- them (warehouses, industry, and work- access from the north. The electrifica- ing Irom Prairie and Louisiana, near ing-class residential neighborhoods) do tion of the streetcar system in 1891 Market Square, up to Milam and Clay, not penetrate downtown Market makes possible a great expansion of near the eastern edge of the African- Square is rebuilt with new brick build- the public transportation network, American residential district in Fourth Main Street looking north from Preston Avenue. 1858 ings to serve the food trades Two which reinforces the primacy of down- Ward. -

Major Lease Transactions Downtown Houston

MAJOR LEASE TRANSACTIONS DOWNTOWN HOUSTON This is a comprehensive list of publicly-available leases in downtown Houston, including new-to-downtown, expansions, and renewals. Year Company Type To From Initial SF JP Morgan Chase Tower 2019 Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP Renewal 134,763 (600 Travis) 2019 Calpine Renewal 717 Texas Ave. 126,000 2 Houston Center 105,578 2019 Direct Energy New to Downtown 12 Greenway Plaza (909 Fannin St.) 2019 King & Spalding Renewal 1100 Louisiana 91,264 Spaces GreenStreet 63,429 2019 New to Downtown [coworking space] (1201 Main) 63,233 2019 WeWork New/Expansion 609 Main at Texas Three Allen Center 57,139 2019 EnVen Energy Relocation 609 Main at Texas (333 Clay St.) Two Allen Center 2019 White & Case LLP Relocation 609 Main at Texas 57,315 (1200 Smith St.) (Expansion: 28,962) 2 Houston Center Pennzoil Place 2019 Gensler Relocation 45,000 (909 Fannin St.) (711 Louisiana St.) Life Time Work GreenStreet 2019 New to Downtown/Houston 37,681 [coworking space] (1201 Main) 2019 Golden Pass LNG Relocation 811 Louisiana St. Allen Center 31,834 Bank of America Tower Enterprise Plaza 2019 Shearman & Sterling, LLP Relocation/Expansion 31,257 (800 Capitol St.) (1100 Louisiana St.) Bank of America Center 2019 BMO Capital Markets Corp Renewal /Expansion 30,275 (700 Louisiana St.) (Expansion: 7,065) Source: Central Houston, Inc. Updated 07-15-2019. 1 Year Company Type To From Initial SF Bank of America Center (700 2019 Smyser Kaplan & Veselka LLP (HQ) Relocation/Expansion 609 Main at Texas 27,795 Louisiana St.) (Expansion: 5,407) Netherland Sewell & Associates, Inc. -

Development Plat Submittal Requirements

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department PROTECTED LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Emancipation Park AGENDA ITEM: III OWNER: City of Houston HPO FILE NO: 07PL46 APPLICANT: City of Houston Parks and Recreation Department DATE ACCEPTED: 07/30/07 LOCATION: 3018 Dowling Street, Houston, Texas 77004 HAHC HEARING DATE: 08/22/07 30-DAY HEARING NOTICE: N/A PC HEARING DATE: 08/30/07 SITE INFORMATION: A ten-acre parcel described as Lot No. 25 in the James S. Holman Survey, within the limits of the City of Houston, Harris County, Texas, on the south side of Buffalo Bayou and bordered by Hutchins Street, Tuam Avenue, Dowling Street, and Elgin Avenue. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark and Protected Landmark Designation for Emancipation Park, including the Park Buildings. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY: Emancipation Park, located in Houston’s Third Ward, is the oldest park site in the City of Houston. It was originally part of the land granted in 1839 to James S. Holman, who had served as Houston’s first mayor. The parcel was purchased in 1872 by a group of black community leaders for the celebration of Juneteenth (the anniversary of the emancipation of African-Americans in Texas on June 19, 1865), and it was donated to the City of Houston in 1916. For more than twenty years, Emancipation Park was the only public park in Houston open to African-Americans. In 1938-39, the Public Works Administration constructed on the park site a recreation center, swimming pool, and bathhouse, designed by prominent Houston architect William Ward Watkin.