Houston Teachers Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Flyleaf, 1988

RICE UNIVERSITY FONPREN LIBRARY Founded under the charter of the univer- sity dated May 18, 1891, the library was Board of Directors, 1988-1989 established in 1913. Its present facility was dedicated November 4, 1949, and rededi- cated in 1969 after a substantial addition, Officers both made possible by gifts of Ella F. Fondren, her children, and the Fondren Foundation and Trust as a tribute to Mr. Edgar O. Lovett II, President Walter William Fondren. The library re- Mrs. Frank B. Davis, Vice-President, Membership corded its half-millionth volume in 1965; Mr. David S. Elder, Vice-President, Programs its one millionth volume was celebrated Mrs. John L Margrave, Vice-President, Special Event April 22, 1979. Mr. J. Richard Luna, Treasurer Ms. Tommie Lu Maulsby, Secretary Mr. David D. Itz, Immediate Past President Dr. Samuel M. Carrington, Jr., University Librarian (ex- officio) THE FRIENDS OF FONDREN LIBRARY Dr. Neal F. Line, Provost and Vice-President (ex- officio) Chairman of the University the Library The Fnends of Fondren Library was found- Committee on ed in 1950 as an association of library sup- (ex-officio) porters interested in increasing and making Mrs. Elizabeth D. Charles, Executive Director (ex- better known the resources of the Fondren officio) Library at Rice University. The Friends, through members' contributions and spon- sorship of a memorial and honor gift pro- Members at Large gram, secure gifts and bequests and provide funds for the purchase of rare books, manuscripts, and other materials which Mrs. D. Allshouse could not otherwise be acquired by the J. library. Mr. John B. -

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

2016 Report.Pdf

AIA HOUSTON 2016 END OF YEAR REPORT The Houston Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIAH) and Architecture Center Houston (ArCH) are moving in Spring 2017. Looking to the long-term stability of our two organizations, we are purchasing almost 8,000SF of space in the historic 1906 B.A. Riesner Building located at 900 Commerce St. in the heart of Houston’s original downtown just steps from Allen’s Landing, the site of Houston’s founding. The space consists of an approximately 5,400SF store- front space on the corner of Travis and Commerce and an approximately 2,200SF boiler room building located behind the storefront. Murphy Mears Architects was selected to design the new center through a competitive process. AIA HOUSTON 2016 END OF YEAR REPORT 2016 MEMBERSHIP TRENDS AS SO C IA T E M E M B E R S S R E E M B E M R E I M T U T S C E T I H C R A PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATES CONTINUING EDUCATION GALA The 2016 Celebrate Architecture Gala raised funds for the Houston Architecture Foundation, as well as granted the opportunity to recognize esteemed members of AIA Houston. Gala chair Caryn Ogier, AIA spearheaded the event with the theme Rendezvous Houston. The event had record attendance, with over 900 people in attendance and raising over $300,000. 2016 AIA President David Bucek addressed the party to announce the year’s Firm of the Year Award winner and Ben Brewer Young Architect Award winner: StudioMET Architects and Brett Zamore, AIA. -

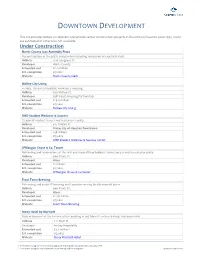

Downtown Development Project List

DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT This list provides details on all public and private sector construction projects in Downtown Houston since 1995. Costs are estimated or otherwise not available. Under Construction Harris County Jury Assembly Plaza Reconstruction of the plaza and pavilion including relocation of electrical vault. Address 1210 Congress St. Developer Harris County Estimated cost $11.3 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Harris County Clerk McKee City Living 4‐story, 120‐unit affordable‐workforce housing. Address 626 McKee St. Developer Gulf Coast Housing Partnership Estimated cost $29.9 million Est. completion 4Q 2021 Website McKee City Living UHD Student Wellness & Success 72,000 SF student fitness and recreation facility. Address 315 N Main St. Developer University of Houston Downtown Estimated cost $38 million Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website UHD Student Wellness & Success Center JPMorgan Chase & Co. Tower Reframing and renovations of the first and second floor lobbies, tunnel access and the exterior plaza. Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website JPMorgan Chase & Co Tower Frost Town Brewing Reframing and 9,100 SF brewing and taproom serving locally inspired beers Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2.58 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Frost Town Brewing Moxy Hotel by Marriott Redevelopment of the historic office building at 412 Main St. into a 13‐story, 119‐room hotel. Address 412 Main St. Developer InnJoy Hospitality Estimated cost $4.4 million P Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website Moxy Marriott Hotel V = Estimated using the Harris County Appriasal Distict public valuation data, January 2019 P = Estimated using the City of Houston's permitting and licensing data Updated 07/01/2021 Harris County Criminal Justice Center Improvement and flood damage mitigation of the basement and first floor. -

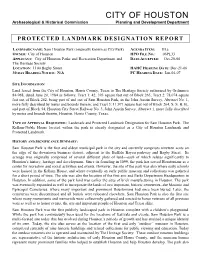

Protected Landmark Designation Report

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department PROTECTED LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Sam Houston Park (originally known as City Park) AGENDA ITEM: III.a OWNER: City of Houston HPO FILE NO.: 06PL33 APPLICANT: City of Houston Parks and Recreation Department and DATE ACCEPTED: Oct-20-06 The Heritage Society LOCATION: 1100 Bagby Street HAHC HEARING DATE: Dec-21-06 30-DAY HEARING NOTICE: N/A PC HEARING DATE: Jan-04-07 SITE INFORMATION: Land leased from the City of Houston, Harris County, Texas to The Heritage Society authorized by Ordinance 84-968, dated June 20, 1984 as follows: Tract 1: 42, 393 square feet out of Block 265; Tract 2: 78,074 square feet out of Block 262, being part of and out of Sam Houston Park, in the John Austin Survey, Abstract No. 1, more fully described by metes and bounds therein; and Tract 3: 11,971 square feet out of Block 264, S. S. B. B., and part of Block 54, Houston City Street Railway No. 3, John Austin Survey, Abstract 1, more fully described by metes and bounds therein, Houston, Harris County, Texas. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark and Protected Landmark Designation for Sam Houston Park. The Kellum-Noble House located within the park is already designated as a City of Houston Landmark and Protected Landmark. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY: Sam Houston Park is the first and oldest municipal park in the city and currently comprises nineteen acres on the edge of the downtown business district, adjacent to the Buffalo Bayou parkway and Bagby Street. -

CURRICULUM VITAE CHELLIAH SRISKANDARAJAH November 2020 I. ACADEMIC HISTORY PERSONAL DATA Status : Hugh Roy Cullen Chair in Busin

CURRICULUM VITAE CHELLIAH SRISKANDARAJAH November 2020 I. ACADEMIC HISTORY PERSONAL DATA Status : Hugh Roy Cullen Chair in Business Administration Mays Business School, Texas A & M University Address: Department of Information and Operations Management Mays Business School Texas A & M University 320 Wehner Building/4217 TAMU College Station, Texas 77843-4217 U.S.A Phone: 979-862-2796 (direct line), 979-845-1616 (main office line) Fax: 979-845-5653 E-mail: [email protected] Nationality: US Citizen (origin SriLanka) EDUCATION University of Toronto, Faculty of Management, Canada (1986-1987). - Post Doctoral Fellow. Higher National School of Electrical Engineering, National Polytechnic Institute of Grenoble, France (1982-1986). (Ecole Nationale Sup´erieured'Ing´enieursElectriciens, Labora- toire d'Automatique, Institut National Polytechnique de Grenoble, France). - Ph.D (Title in French: Diplome de Docteur). Field: Automation, Operations Research. - Received this degree with DISTINCTION grade (grade in French \TRES HONORABLE"). - Dissertation : L'Ordonnancement dans les ateliers : complexite et algorithmes heuristiques (Shop scheduling : complexity and heuristic algorithms). - Adviser : Professor Pierre Ladet. Universit´eScientifique et Medicale de Grenoble, France (1982-1983). (Laboratoire d'Informatique et de Math´ematiquesappliqu´eede Grenoble). - M.Sc. degree (Title in French: DEA). Field: Operations Research. 1 Asian Institute of Technology (A.I.T.) Bangkok, Thailand (1979-1981) - Master of Engineering Degree in Industrial Engineering and Management. Received this degree with an overall grade point average of 3.83 out of 4. - Thesis : Production scheduling model for a sanitaryware manufacturing company. - Adviser : Professor Pakorn Adulbhan. University of Moratuwa, SriLanka (1973-1977) - B.Sc. Engineering Degree (graduated with Honors) in Mechanical Engineering. AWARDS AND HONORS - Best Department Editor Award 2018: POM Journal, May 2018. -

30Th Anniversary of the Center for Public History

VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2015 HISTORY MATTERS 30th Anniversary of the Center for Public History Teaching and Collection Training and Research Preservation and Study Dissemination and Promotion CPH Collaboration and Partnerships Innovation Outreach Published by Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 28½ Years Marty Melosi was the Lone for excellence in the fields of African American history and Ranger of public history in our energy/environmental history—and to have generated new region. Thirty years ago he came knowledge about these issues as they affected the Houston to the University of Houston to region, broadly defined. establish and build the Center Around the turn of the century, the Houston Public for Public History (CPH). I have Library announced that it would stop publishing the been his Tonto for 28 ½ of those Houston Review of History and Culture after twenty years. years. Together with many others, CPH decided to take on this journal rather than see it die. we have built a sturdy outpost of We created the Houston History Project (HHP) to house history in a region long neglectful the magazine (now Houston History), the UH-Oral History of its past. of Houston, and the Houston History Archives. The HHP “Public history” includes his- became the dam used to manage the torrent of regional his- Joseph A. Pratt torical research and training for tory pouring out of CPH. careers outside of writing and teaching academic history. Establishing the HHP has been challenging work. We In practice, I have defined it as historical projects that look changed the format, focus, and tone of the magazine to interesting and fun. -

LATINOS in HOUSTON Trabajando Para La Comunidad Y La Familia

VOLUME 15 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2018 LATINOS IN HOUSTON Trabajando para la comunidad y la familia CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY LETTER FROM THE EDITOR savvy businessmen making it a commercial hub. By the What is Houston’s DNA? 1840s, Germans were coming in large numbers, as were “Discover your ethnic origins,” find other European immigrants. The numbers of Mexicans and the “source of your greatness,” trace Tejanos remained low until the 1910s-1920s, reaching about your “health, traits, and ancestry,” 5% in 1930. African Americans made up almost a quarter and “amaze yourself…find new rela- of the population, with their numbers growing during the tives.” Ads proliferate from companies Great Migration and with the influx of Creoles throughout like AncestryDNA, 23andMe, and the 1920s. MyHeritage enticing us to learn more Houston’s DNA, like the nation's, remained largely about who we really are. European due to federal laws: The Chinese Exclusion Acts Debbie Z. Harwell, People who send a saliva sample for of 1882, 1892, and 1902; the Immigration Act of 1924, which Editor analysis may be completely surprised by imposed quotas mirroring each ethnic group’s representa- the findings or even united with unknown family members. tion in the population and maintained the existing racial For others it either confirms or denies what they believed order; and the Mexican Repatriation Act of 1930, which about their heritage. For example, my AncestryDNA report permitted deportation of Mexicans — even some U.S. cit- debunks the story passed down by my mother and her izens — to relieve the stress they allegedly placed on the blonde-haired, blue-eyed siblings that their grandmother, economy. -

Center for Public History

Volume 8 • Number 2 • spriNg 2011 CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY Oil and the Soul of Houston ast fall the Jung Center They measured success not in oil wells discovered, but in L sponsored a series of lectures the dignity of jobs well done, the strength of their families, and called “Energy and the Soul of the high school and even college graduations of their children. Houston.” My friend Beth Rob- They did not, of course, create philanthropic foundations, but ertson persuaded me that I had they did support their churches, unions, fraternal organiza- tions, and above all, their local schools. They contributed their something to say about energy, if own time and energies to the sort of things that built sturdy not Houston’s soul. We agreed to communities. As a boy, the ones that mattered most to me share the stage. were the great youth-league baseball fields our dads built and She reflected on the life of maintained. With their sweat they changed vacant lots into her grandfather, the wildcatter fields of dreams, where they coached us in the nuances of a Hugh Roy Cullen. I followed with thoughts about the life game they loved and in the work ethic needed later in life to of my father, petrochemical plant worker Woodrow Wilson move a step beyond the refineries. Pratt. Together we speculated on how our region’s soul—or My family was part of the mass migration to the facto- at least its spirit—had been shaped by its famous wildcat- ries on the Gulf Coast from East Texas, South Louisiana, ters’ quest for oil and the quest for upward mobility by the the Valley, northern Mexico, and other places too numerous hundreds of thousands of anonymous workers who migrat- to name. -

BIGGERS, JOHN THOMAS, 1924-2001. John Biggers Papers, 1950-2001

BIGGERS, JOHN THOMAS, 1924-2001. John Biggers papers, 1950-2001 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Biggers, John Thomas, 1924-2001. Title: John Biggers papers, 1950-2001 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1179 Extent: 31 linear feet (62 boxes), 6 oversized papers boxes and 2 oversized papers folders (OP), 2 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 1 extra-oversized paper (XOP), and AV Masters: .25 linear feet (1 box) Abstract: Papers of African American mural artist and professor John Biggers including correspondence, photographs, printed materials, professional materials, subject files, writings, and audiovisual materials documenting his work as an artist and educator. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, MARCH 14, 2011 No. 38 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was I have visited Japan twice, once back rifice our values and our future all in called to order by the Speaker pro tem- in 2007 and again in 2009 when I took the name of deficit reduction. pore (Mr. CAMPBELL). my oldest son. It’s a beautiful country; Where Americans value health pro- f and I know the people of Japan to be a tections, the Republican CR slashes resilient, generous, and hardworking funding for food safety inspection, DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO people. In this time of inexpressible community health centers, women’s TEMPORE suffering and need, please know that health programs, and the National In- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- the people of South Carolina and the stitutes of Health. fore the House the following commu- people of America stand with the citi- Where Americans value national se- nication from the Speaker: zens of Japan. curity, the Republican plan eliminates WASHINGTON, DC, May God bless them, and may God funding for local police officers and March 14, 2011. continue to bless America. firefighters protecting our commu- I hereby appoint the Honorable JOHN f nities and slashes funding for nuclear CAMPBELL to act as Speaker pro tempore on nonproliferation, air marshals, and this day. FUNDING THE FEDERAL Customs and Border Protection. Where JOHN A. BOEHNER, GOVERNMENT Americans value the sacrifice our men Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

Download All English Factsheets

Astrodome Fact Sheet Spring / Summer 2021 Page 1 / 7 English History of the Astrodome The Astrodome is Houston’s most significant architectural Houston Oilers and cultural asset. Opened in 1965, and soon nicknamed the “8th Wonder of the World,” the world’s first domed stadium was conceived to protect sports spectators from Houston’s heat, humidity, and frequent inclement weather. The brainchild of then-Houston Mayor Roy Hofheinz, the former Harris County Judge assembled a team to finance and develop the Dome, with the help of R.E. Bob Smith, who owned the land the Astrodome was built on and was instrumental in bringing professional baseballs’ Colt 45s (now the Astros) to Houston. The Astrodome was the first Harris County facility specifically designed and built as a racially integrated building, playing an important role in the desegregation of Houston during the Civil Rights Movement. football configuration The Astrodome was revolutionary for its time as the first fully enclosed and air conditioned multi-purpose sports arena - an Football Between 1968 and 1996, the Houston Oilers engineering feat of epic proportions. The innovation, audacity, called1965 1968 the Dome home as well, until1996 the franchise left town2021 and “can-do” spirit of Houston at mid-Century was embodied to become the Tennessee Titans. It served several other in the Astrodome. It was home to multiple professional and professional football teams, including the Houston Texans amateur sports teams and events over the years, as well in 1974, the Houston Gamblers from 1984 to 1985, and the as hosting the annual Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo Houston Energy (an independent women’s football team) (HLSR), concerts, community and political events.