Center for Public History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham, Staff Depart to Mixed Reactions Former President Bill

the Rice Thresher Vol. XCIV, Issue No. 16 SINCE 191# ^4/ < Friday, JanuaJanuarr y 19, 2007 Graham, staff depart to mixed reactions by Nathan Bledsoe offers — is Feb. 7. Tllkl SHI.R KDITORIAl S'l'AI I- President David Leebron, who is currently traveling in India, said he Two clays after signing a contract supports the coaching search. extension Jan. 9, former head football "Chris Del Conte is doing an coach Todd Graham, who led the re- absolutely first-rate job of conduct- surgent team to seven wins in his lone ing this process really expeditiously season at Rice, departed to become and thoughtfully," he said. "He has head coach at the University of Tulsa. assembled a terrific committee CBS Sportsline reported that of people which includes players Tulsa, where Graham was defensive from the team — I think people are coordinator before coming to Rice, really optimistic and excited about the will pay him $1.1 million a year — an future. It's not about just one person; estimated $400,000 increase over his it's about the program." Rice salary. Graham's lone year at Rice was By Jan. 13, Athletic Director Chris marked with much on-the-field Del Conte had formed a commit- success, with the Owls playing in tee and begun the search for a new their first bowl game since 1961. head coach. He also raised enough money to "We are going to strike and get install new Field Turf and a Jumbo- someone here in short order who tron at Rice Stadium, among other is going to take this baton and run upgrades. -

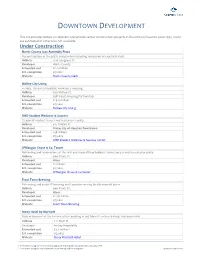

Downtown Development Project List

DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT This list provides details on all public and private sector construction projects in Downtown Houston since 1995. Costs are estimated or otherwise not available. Under Construction Harris County Jury Assembly Plaza Reconstruction of the plaza and pavilion including relocation of electrical vault. Address 1210 Congress St. Developer Harris County Estimated cost $11.3 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Harris County Clerk McKee City Living 4‐story, 120‐unit affordable‐workforce housing. Address 626 McKee St. Developer Gulf Coast Housing Partnership Estimated cost $29.9 million Est. completion 4Q 2021 Website McKee City Living UHD Student Wellness & Success 72,000 SF student fitness and recreation facility. Address 315 N Main St. Developer University of Houston Downtown Estimated cost $38 million Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website UHD Student Wellness & Success Center JPMorgan Chase & Co. Tower Reframing and renovations of the first and second floor lobbies, tunnel access and the exterior plaza. Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website JPMorgan Chase & Co Tower Frost Town Brewing Reframing and 9,100 SF brewing and taproom serving locally inspired beers Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2.58 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Frost Town Brewing Moxy Hotel by Marriott Redevelopment of the historic office building at 412 Main St. into a 13‐story, 119‐room hotel. Address 412 Main St. Developer InnJoy Hospitality Estimated cost $4.4 million P Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website Moxy Marriott Hotel V = Estimated using the Harris County Appriasal Distict public valuation data, January 2019 P = Estimated using the City of Houston's permitting and licensing data Updated 07/01/2021 Harris County Criminal Justice Center Improvement and flood damage mitigation of the basement and first floor. -

CURRICULUM VITAE CHELLIAH SRISKANDARAJAH November 2020 I. ACADEMIC HISTORY PERSONAL DATA Status : Hugh Roy Cullen Chair in Busin

CURRICULUM VITAE CHELLIAH SRISKANDARAJAH November 2020 I. ACADEMIC HISTORY PERSONAL DATA Status : Hugh Roy Cullen Chair in Business Administration Mays Business School, Texas A & M University Address: Department of Information and Operations Management Mays Business School Texas A & M University 320 Wehner Building/4217 TAMU College Station, Texas 77843-4217 U.S.A Phone: 979-862-2796 (direct line), 979-845-1616 (main office line) Fax: 979-845-5653 E-mail: [email protected] Nationality: US Citizen (origin SriLanka) EDUCATION University of Toronto, Faculty of Management, Canada (1986-1987). - Post Doctoral Fellow. Higher National School of Electrical Engineering, National Polytechnic Institute of Grenoble, France (1982-1986). (Ecole Nationale Sup´erieured'Ing´enieursElectriciens, Labora- toire d'Automatique, Institut National Polytechnique de Grenoble, France). - Ph.D (Title in French: Diplome de Docteur). Field: Automation, Operations Research. - Received this degree with DISTINCTION grade (grade in French \TRES HONORABLE"). - Dissertation : L'Ordonnancement dans les ateliers : complexite et algorithmes heuristiques (Shop scheduling : complexity and heuristic algorithms). - Adviser : Professor Pierre Ladet. Universit´eScientifique et Medicale de Grenoble, France (1982-1983). (Laboratoire d'Informatique et de Math´ematiquesappliqu´eede Grenoble). - M.Sc. degree (Title in French: DEA). Field: Operations Research. 1 Asian Institute of Technology (A.I.T.) Bangkok, Thailand (1979-1981) - Master of Engineering Degree in Industrial Engineering and Management. Received this degree with an overall grade point average of 3.83 out of 4. - Thesis : Production scheduling model for a sanitaryware manufacturing company. - Adviser : Professor Pakorn Adulbhan. University of Moratuwa, SriLanka (1973-1977) - B.Sc. Engineering Degree (graduated with Honors) in Mechanical Engineering. AWARDS AND HONORS - Best Department Editor Award 2018: POM Journal, May 2018. -

Dor to Door SOCIETY

GREATER HOUSTON JEWISH GENEALOGICAL Dor to Door SOCIETY Summer 2017 HOUSTON, TEXAS Joseph M. Sam, One-Term Houston City Attorney & Philanthropist Inside this issue: He was born on 23 December 1865, Travis, Austin Co., TX Officers / Meeting 2 and was the son of Samuel Sam and Caroline Stern. His Dates / Dues siblings were: Henrietta Sam (Miss), Simon L. Sam, Jacob W. Sam, Nathan Sam, Levi Sam and Sarah Ann Sam Sam Facebook & Website 2 (Mrs. Jake H. Sam). Texas Jewish His- 3 On 14 June 1900, Houston, Harris Co., TX, he married torical Soc Meeting Idaho Zorkowsky. There were no children. On 22 April 1920 Suggested Reading 3 in Galveston, Galveston County, Texas, Idaho married Max Wile. She died on 8 Feb 1957 in New York and was buried Houston Handbook 3 with her second husband in the Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buf- falo, Erie Co., NY. Longview Jewish 4 Cemetery & HTCD Joe died on 14 Feb 1915 in Houston of pneumonia and chronic asthma. He was buried in the Beth Israel Cemetery (West Dallas), Houston. On the day of Restoration of Fort 5 his funeral, the bell at the Old City Hall tolled all afternoon and the courts were Worth WWI Memo- rial closed in his honor. At an early age Sam "read for the law" in the offices of William Paschal "W. Houston WWII Vets 5 P." Hamblen who would serve as Judge, 55th District Court, Harris County from Military Awards 1902 until his death in 1911. Three Brothers Bak- 6 At the time of Sam's death, he was the senior member of the law firm of Sam, ery - Treasured Bradley & Fogle. -

BERNAL-THESIS-2020.Pdf (5.477Mb)

BROWNWOOD: BAYTOWN’S MOST HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOOD by Laura Bernal A thesis submitted to the History Department, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Chair of Committee: Dr. Monica Perales Committee Member: Dr. Mark Goldberg Committee Member: Dr. Kristin Wintersteen University of Houston May 2020 Copyright 2020, Laura Bernal “A land without ruins is a land without memories – a land without memories is a land without history.” -Father Abram Joseph Ryan, “A Land Without Ruins” iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, and foremost, I want to thank God for guiding me on this journey. Thank you to my family for their unwavering support, especially to my parents and sisters. Thank you for listening to me every time I needed to work out an idea and for staying up late with me as I worked on this project. More importantly, thank you for accompanying me to the Baytown Nature Center hoping to find more house foundations. I am very grateful to the professors who helped me. Dr. Monica Perales, my advisor, thank you for your patience and your guidance as I worked on this project. Thank you to my defense committee, Dr. Kristin Wintersteen and Dr. Goldberg. Your advice helped make this my best work. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Debbie Harwell, who encouraged me to pursue this project, even when I doubted it its impact. Thank you to the friends and co-workers who listened to my opinions and encouraged me to not give up. Lastly, I would like to thank the people I interviewed. -

Summer SAMPLER VOLUME 13 • NUMBER 3 • SUMMER 2016

Summer SAMPLER VOLUME 13 • NUMBER 3 • SUMMER 2016 CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY Published by Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative Last LETTER FROM EDITOR JOE PRATT Ringing the History Bell fter forty years of university In memory of my Grandma Pratt I keep her dinner bell, Ateaching, with thirty years at which she rang to call the “men folks” home from the University of Houston, I will re- fields for supper. After ringing the bell long enough to tire at the end of this summer. make us wish we had a field to retreat to, Felix, my For about half my years at six-year old grandson, asked me what it was like to UH, I have run the Houston live on a farm in the old days. We talked at bed- History magazine, serving as a time for almost an hour about my grandparent’s combination of editor, moneyman, life on an East Texas farm that for decades lacked both manager, and sometimes writer. In the electricity and running water. I relived for him my memo- Joseph A. Pratt first issue of the magazine, I wrote: ries of regular trips to their farm: moving the outhouse to “Our goal…is to make our region more aware of its history virgin land with my cousins, “helping” my dad and grandpa and more respectful of its past.” We have since published slaughter cows and hogs and hanging up their meat in the thirty-four issues of our “popular history magazine” devot- smoke house, draw- ed to capturing and publicizing the history of the Houston ing water from a well region, broadly defined. -

Timeless Designs Tasting Menus the Art of the Exhibition

AUSTIN-SAN ANTONIO URBAN OCT/NOV 14 HCELEBRATING OINSPIRATIONAL DESIGNME AND PERSONAL STYLE TIMELESS DESIGNS TASTING MENUS THE ART OF THE EXHIBITION www.UrbanHomeMagazine.com Woodworking at its finest TRADITIONAL ... TUSCAN ... OLD WORLD ... CONTEMPORARY ... MODERN ... COMMERCIAL ... FURNITURE KINGWOOD HAS PRODUCED IN EXCESS OF 5000 KITCHENS AND RELATED PROJECTS IN ITS 40 YEAR HISTORY. WE HAVE OUR FURNITURE GRADE CUSTOM CABINETRY DESIGNS GRACING HOMES THROUGHOUT TEXAS AND THE UNITED STATES . FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PLEASE VISIT OUR FREDERICKSBURG SHOWROOM. 401 South Lincoln Street 830.990.0565 Fredericksburg, Texas 78624 www.kingwoodcabinets.com Pool Maintenance: Pool Remodeling • Personalized Pool Service Specialists: • First month free with 6 month commitment • Pool Re-Surfacing • Equipment Repair and Replacement (210) 251-3211 • Coping, Tile, Decking and Rockwork Custom Pool Design and Construction www.artesianpoolstx.com FROM THE EDITOR Interior design styles have many names: contemporary, traditional, rustic, retro, French country… the list goes on and on. But what about timeless design? To marry two or more styles, combine old and new, incorporate a lot of homeowner personality, and then carefully edit the details to create the perfect space is just what the designers in this issue accomplished. This timeless design has no restrictions or limits, is durable and sustainable, and will remain beautiful and fashionable as time goes on. When Royce Flournoy of Texas Construction Company set out to build his personal home, he called on his colleagues at FAB Architecture. They had collaborated on many projects before, and Flournoy knew that their combined visions would result in architecture that ages gracefully and allows furnishings and art to remain in the forefront. -

ASME National Historical Mechanical Engineering Landmark Program 1975

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC U.S.S. Texas AND/OR COMM Battleship Texas LOCATION -T& NUMBER San Jacinto Battleground State Park STREETea. &NUr "2? mi. east of Houston on Tex. 13* _NOTFORPUBL1CAT10N CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF Houston STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Texas Harris 201 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —XPUBLIC .XOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _ PARK' —STRUCTURE . —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS .XEDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS ^•.OBJECT _IN PROCESS .XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT -^SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY Contact: C.H. Taylor, Chairman NAME State of Texas, The Battleship Texas Commission STREET & NUMBER EXXON Building; Suite 2695 CITY, TOWN STATE Houston VICINITY OF Texas LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. The Battleship Texas Commission STREET & NUMBER EXXON Building. Suite 26QR CITY, TOWN STATE Houston Texas REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE ASME National Historical Mechanical Engineering Landmark Program DATE 1975 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS ASME United Engineering Center CITY. TOWN New York DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE X_GOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED X_MOVED DATE 1948 —FAIR — UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company built Texas (BB35) in 1911-14. Upon her completion she measured 573 feet long, was 94 3/4 feet wide at the beam, had a normal displacement of 27,000 tons and a mean draft of 28 1/2 feet, and boasted a top speed of 21 knots. -

Meet Me at the Flagpole: Thoughts About Houston’S Legacy of Obscurity and Silence in the Fight of Segregation and Civil Right Struggles

Meet Me at the Flagpole: Thoughts about Houston’s Legacy of Obscurity and Silence in the fight of Segregation and Civil Right Struggles Bernardo Pohl Abstract This article focuses on the segregated history and civil right movement of Houston, using it as a case study to explore more meaningfully the teaching of this particular chapter in American history. I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made straight and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I remember the day very clearly. It was an evening at Cullen Auditorium at Uni- versity of Houston. It was during the fall of 2002, and it was the end of my student teach- ing. Engulfed in sadness, I sat alone and away from my friends. For me, it was the end of an awesome semester of unforgettable moments and the start of my new teaching career. I was not really aware of the surroundings; I did not have a clue about what I was about to experience. After all, I just said yes and agreed to another invitation made by Dr. Cam- eron White, my mentor and professor. I did not have any idea about the play or the story that it was about to start. The word “Camp Logan” did not evoke any sense of familiarity in me; it did not resonate in my memory. Besides, my mind was somewhere else: it was in the classroom that I left that morning; it was in the goodbye party that my students prepared for me; and it was in the uncertain future that was ahead of me. -

Houstonhouston

RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Texas A&M University July 2001 © 2001, Real Estate Center. All rights reserved. RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Contents 2 Note Population 6 Employment 9 Job Market 10 Major Industries 11 Business Climate 13 Public Facilities 14 Transportation and Infrastructure Issues 16 Urban Growth Patterns Map 1. Growth Areas Education 18 Housing 23 Multifamily 25 Map 2. Multifamily Building Permits 26 Manufactured Housing Seniors Housing 27 Retail Market 29 Map 3. Retail Building Permits 30 Office Market Map 4. Office Building Permits 33 Industrial Market Map 5. Industrial Building Permits 35 Conclusion RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Aldine Jersey Village US Hwy 59 US Hwy 290 Interstate 45 Sheldon US Hwy 90 Spring Valley Channelview Interstate 10 Piney Point Village Houston Galena Park Bellaire US Hwy 59 Deer Park Loop 610 Pasadena US Hwy 90 Stafford Sugar Land Beltway 8 Brookside Village Area Cities and Towns Counties Land Area of Houston MSA Baytown La Porte Chambers 5,995 square miles Bellaire Missouri City Fort Bend Conroe Pasadena Harris Population Density (2000) Liberty Deer Park Richmond 697 people per square mile Galena Park Rosenberg Montgomery Houston Stafford Waller Humble Sugar Land Katy West University Place ouston, a vibrant metropolitan City Business Journals. The city had a growing rapidly. In 2000, Houston was community, is Texas’ largest population of 44,633 in 1900, growing ranked the most popular U.S. city for Hcity. Houston was the fastest to almost two million in 2000. More employee relocations according to a growing city in the United States in the than four million people live in the study by Cendant Mobility. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks August 4, 2007 LILLY LEDBETTER FAIR PAY ACT Dedicated Hero of the Fort Worth Community Placeable Community Figure

E1776 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks August 4, 2007 LILLY LEDBETTER FAIR PAY ACT dedicated hero of the Fort Worth community placeable community figure. Marvin’s father OF 2007 and of our Nation. Abe, who openly opposed the Ku Klux Klan Cpl James H. McRae was a proud United and was a card-carrying member of the SPEECH OF States Marine and a true American hero who NAACP, helped instill in Marvin the values that HON. AL GREEN gallantly and selflessly gave his life for his made him so valued in the community. As a OF TEXAS country on July 24 during combat operations newsman, Marvin became a pioneer in con- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES in Diyala Province, Iraq. sumer reporting and a tireless advocate for James enlisted in the toughest of the mili- Tuesday, July 31, 2007 those who, without his assistance, would be tary branches during time of war, which without a voice in having their needs ad- Mr. AL GREEN of Texas. Madam Speaker, speaks volumes about his character and patri- dressed. I rise in strong support of H.R. 2831, the Lilly otism. Mr. Zindler initially came to prominence Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2007, which will cor- Assigned to the Marine Expeditionary Force, through a week long special on the ‘‘Chicken rect a gross injustice done in the recent Su- James was a non-commissioned officer—the Ranch,’’ an illegal brothel just outside of La preme Court decision in the case Ledbetter v. backbone of the corps and a true leader. Grange, TX, that local authorities tolerated for Goodyear. -

A Conversation with Jane Blaffer Owen and Elizabeth Gregory, Joe

R ecalling Houston’s Early Days and Its Oilmen: A Conversation with Jane Blaffer Owen and Elizabeth Gregory, Joe Pratt, and Melissa Keane ane Blaffer Owen, an arts patron, social activist, and preservationist, was the daughter of Robert Lee Blaffer, one Jof the founders of Humble Oil & Refining Company (now ExxonMobil), and the granddaughter of William T. Campbell, who established the The Texas Company, which became Texaco. She was born on April 18, 1915, and grew up in the family home at 6 Sunset Boulevard in Houston. She attended the Kinkaid School, and graduated from the Ethel Walker School in Simsbury, Connecticut. She studied at Bryn Mawr College and Union Theological Seminary. In 1941, she married Kenneth Owen, a descendant of New Harmony Utopian Society founder Robert Owen. Recognized for her philanthropy in both Houston, Texas, and New Harmony, Indiana, Blaffer Owen was a life-long supporter of the University of Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum and a patron of the Moores School of Music and College of Architecture. She received many awards and honorary degrees over the years. In 2009, Jane Blaffer Owen achieved the highest honor given by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Crowninshield Award. Although dividing her time between Houston and New Harmony, a historic town founded by her father-in-law as a utopian community, Blaffer Owen served as the first president of Allied Arts Council, as an early organizer of the Seamen’s Center, as a trustee of the C. G. Jung Education Center, and as a board member of the Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation— demonstrating her community activism in the Bayou City.